Porridge at Ballinluig

He stood motionless in his grey box, a sentinel of sorts in a breeze block buffet dispensing cigarettes, gum and glossy magazines. Only his eyes moved, sliding slowly from side to side, as I paced the rain-pelted platform. The train was delayed, but it felt deliberate, as though someone with a grudge at London Underground had put me in the crosshairs, and in my jittery state it seemed the creepy vendor could be part of that conspiracy. Several times I tried to write in my notebook in an effort to get a conversation of sorts going, but I could only produce scars in the damp, ink-resistant pages. An hour passed pacing this blank wordless rut, and when the train did at last trundle into the station, it was instantly clear from the steamy windows and unfriendly faces pressed against them that there was no room on board.

A long day, and home a long way off. On a cold metal bench, sheltered at the far end of the platform, I closed my eyes and was rescued by a Buckie Drifter trailed by seagulls laughing madly as it crossed the choppy waters to somewhere else, somewhere better – a place far beyond this dead empty night.

An angry voice brought me back to the world with a splash. From a train carriage on the platform opposite, a man yelled at a teenager blocking the automatic doors; he was holding them open for a bedraggled woman struggling along the platform, a woman of indeterminate age battling, bent-backed and bundled with laundry bags, towards the train – someone you might expect to see living under a bridge or in a shop doorway. Hunched up in my best, albeit nippit, Barnardos blazer, I stared into the cold grey platform concrete and tried to imagine the possible otherness Marx had in mind for people like you and me and her, but just as in a world without social class there would remain a tribal ‘them’ and ‘us’, it appeared inevitable that even in a world without want there would be those without pity. Perhaps it was the dour setting, the dismal drips and desolation – hardly the place to conjure images of utopia – and so I delved into the archives and played back an old favourite: a porridge joint in Ballinluig, gateway to the highlands, hundreds of miles from platform hell, where I slid into a seat at a window table and, in calm contemplation, quietly considered the realm of the little birds forming fern-like footprints and hieroglyphic patterns in the snow.

In the time spent rumbling and rattling through tunnels, I sat opposite an elderly man who was buried in thought. His wide open coat revealed a belly-distended T-shirt emblazoned with ghostly lettering: something, something, ‘the nightmare dead’. The words dripped over an illustration of a zombie gorging on human brains, and I began to realise how very far I was from Ballinluig. In spite of the zombie, or perhaps because of it, the opening to Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte was resurrected: ‘The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’. The words were a rejoinder to Hegel, but they had their source in Adam Ferguson – a man born close to where the Ballinluig porridge joint now stood.

I wondered how Marx and Ferguson might see the world today. In Marx’s milieu, the ruling class dismissed the condition of the lower classes as the workings of divine providence. The majority who produced the wealth lived in slums, the sick or feeble died earlier than they ought, and families were forced into workhouses or prison or onto the street, and whilst there were those who insisted there is brass in the muck, most poor folk just found muck and more muck. His was an age of absolutes and obvious obscenity – extreme exploitation, extreme wealth, extreme poverty – an age where dominant class interests were rigidly upheld and expressed through the power of the state. In both its absolute and relative forms, of course, poverty perpetually persists as a corollary of capital accumulation – at the bottom of the pyramid, over two billion live on £1 a day – and were he sitting opposite, breathing in potentially deadly particulates as the train threaded through airless tunnels, thundering east to west under grand buildings where they worship God, neighbouring those where they worship money, Marx might reflect on the definite lines of continuity between the London he left in 1883 and the one that exists now; he would doubtless conclude capitalism can conceivably run forever, albeit under unspeakable conditions of authoritarian control, cruelty and carnage. But the alternatives are not necessarily better, and some calling themselves Marxist – Marx stated he was not one of them – have displayed extraordinary ideas about how to turn the world red.

Ferguson helped colour Marx’s portrait of capitalist society, though there was little red on his palette. He stated the now standard sociological tenet that we are the product of history and of the society in which we live, and maintained the future of the human race depends on how far we challenge and change that society – free and flourishing, totalitarian and tyrannical, the extremes are within our power. Given this position on the dual possibilities open to us, it is perhaps not surprising his writings should influence Marx, but also that antagonist of Marxism – the most powerful exponent of neoliberalism, or market fundamentalism – Friedrich Von Hayek.

There was in fact a persistent duality to Ferguson’s life: he contributed to the composition of the American Constitution, but opposed the American War of Independence; his political philosophy is described as proto-Marxist, yet his support for equality is in doubt; he justified the union with England on the basis of economic prosperity, but abhorred the falling moral standards that accompanied that prosperity, (notably among the lowlanders); he was fiercely anti-Jacobite and condemned the highlanders, yet confessed a certain sympathy for them, albeit belatedly, conceding that they had after all fought from a far higher moral position; he served as a chaplain in the Black Watch – and possibly under the Duke of Cumberland at the Battle of Fontenoy – but he was also a skilled and somewhat enthusiastic swordsman, and reportedly was urged to dampen his zeal for the blade (he was once pulled back off the battlefield under orders by his colonel). He was not at the last battle fought on British soil, the Battle of Culloden – a massacre, actually – but there is no doubt he supported the Duke of Cumberland and the crushing of the highland clans.

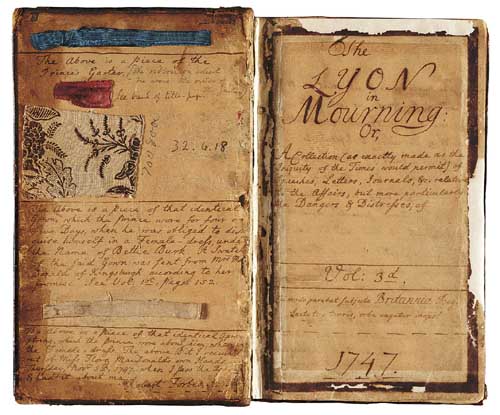

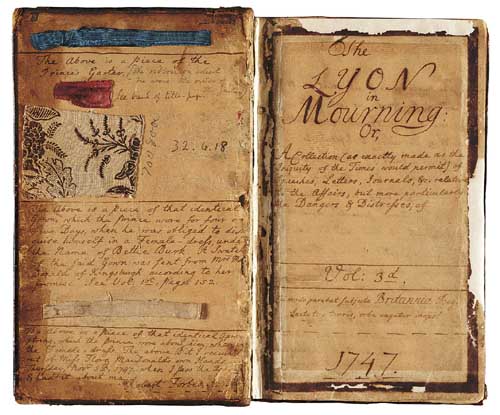

An oft-quoted figure of speech used by Ferguson was “He’ll be slaughtered like a highlander”, but he otherwise made little reference to the massacre of his fellow countrymen at Culloden – to the manner of their death and the fate of their families – yet he would have been familiar with the events of this extraordinary battle and the aftermath, as would all in his social position: the continued slaughter of officers and men, the rape of their wives and the abandonment of their children to a short life of begging. He knew that the wounded were dragged back to the battlefield and their faces bludgeoned with rifle butts. Others, seeking refuge in barns and the like, were locked in and burned alive. He knew that officers and men were tortured for sport during their passage as prisoners on ships to London, and that those who survived were mutilated at Southwark. From The Lyon in Mourning:

Three days after the battle, at 4 miles distance, the sogers most barbarously cut a woman in many places of her body, particularly in the face…They would hardly allow his wife time to take her rings of her fingers, but were going to cutt of her fingers, having stript her of her cloaths, her house and effects being burnt. And in the braes of Glenmoriston a party there ravishd a gentlewoman big with child, and tenants’ wives, and left them on the ground after they were ravishd by all the party.

This in an age of genius, the Scottish Enlightenment – an age in which Voltaire wrote, “We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation.” The dead tell a different story.

In his final months, wrapped behind the old cold walls of the castle of Neidpath, near Peebles, Adam Ferguson stared into the black starless night. From considering the destiny of the human race, he was led now to look at the future of the planet itself; he would never before have seen weather like this: winter in summer, strange, tempestuous skies and bizarre lightning storms. He would learn of sudden and dramatic weather changes throughout the world leading to increased levels of hunger, disease, mass migrations and death. It may indeed have been this long cold winter that occasioned his death in that year, 1816 – the one without a summer. The climate in which Ferguson lived was extreme: the massacre at Culloden, the Scottish enlightenment, the French revolution, the American revolutionary war, the Napoleonic wars – global war, in fact, resulting in a radically changed map of the world. Living in an extreme climate, it is perhaps apt that he should die in one.

The contribution made by Ferguson to the political philosophy of Marx snowballed in the following century, and at the end of the Great War a large section of the world’s population proclaimed itself Marxist. By the close of the Second World War, following a huge human sacrifice to defeat the Nazis, Russia’s Red Army marched into Germany heralding an era of peace and socialism founded on Marxist principles. As celebrations erupted throughout the world to mark the end of the European part of the war, flags and banners bearing swastikas were dragged down from public buildings and converted into ones bearing the hammer and sickle. Women were then dragged out from basement shelters, dragged out from the ruins, the makeshift hospitals and maternity wards; they were dragged out onto the streets, stripped and gang-raped under the red flags planted high on what remained of city buildings. Women were mutilated with broken bottles by drunken soldiers, and others were beaten to a pulp. Suicides soared to levels unprecedented in human history. Many escaped the terror by self-poisoning, assisted by chemists, or by throwing themselves off buildings and bridges. Elderly males trying to save their granddaughters or wives, or boys trying to save their sisters, were shot out of hand. Red Army, but also Allied soldiers, raped more than two million German women, many of them young girls aged twelve or under, and at least a quarter of a million died from injuries that were sustained during the rapes, or from suicide, or murder. From A woman in Berlin:

No sound. Only an involuntary grinding of teeth when my underclothes are ripped apart. The last untorn ones I had. Suddenly his finger is in my mouth, stinking of horse and tobacco. I open my eyes. A stranger’s hand expertly pulling apart my jaw. Eye to eye. Then with great deliberation he drops a gob of gathered spit in my mouth.

If it were possible I would have travelled across London by bus instead of the tube every day. Unlike London Underground platforms, where there are few recorded flashes of genius, for reasons unknown many notable ideas formed on buses. On the number 28 that ran past my place in Notting Hill, the lyrics to one of the most famous songs in history were drafted: The Red Flag anthem. The author, Jim Connell – an Irishman from County Meath – was a docker blacklisted for unionising the workers; he came to London where he worked for a time as a staff journalist on Keir Hardie’s paper, The Labour Leader. Transport and labour historians battle over whether his inspiration came out of the blue on a bouncy bus or on a train watching the red flag being raised and lowered by a railway signalman – RMT leader, Bob Crow, did not take sides in the dispute when he unveiled Connell’s plaque in Crosskiel in 2007. Connell regularly took the 28 bus to his home in New Cross, South London, and it is likely that en route in 1889, six years after the death of Marx, the words jostled and joined together. Had he been pacing a damp and dingy platform such as the one I was on, he would not have been able to jot down words at all.

Connell campaigned for workers’ rights, and railed against the ruling class and their political representatives, but he also wanted us to remember Culloden, to remember the fall of the highlanders and their ongoing oppression, and to this end he asked that his lyrics be sung to the air of the pro-Jacobite anthem, The White Cockade.

Come dungeons dark, or gallows grim,

This song shall be our parting hymn.

When he was awarded the Red Star Medal by Lenin in 1922, Connell had in mind the unity of the proletarian class, to this day the fastest growing class on earth – an aspiration far from the reality of a young girl raped among the shelled-out buildings of Berlin by brutal thugs. He would perhaps be surprised to learn how slowly the march has moved towards socialism, and the roads it sometimes follows. The young girl lying on the street may have thought how agonisingly slowly this deepest red flag blew in the breeze on the buildings above, moving this way and that.

Really enjoy your writing Paul. It evokes so many memories and emotions – being a Glaswegian Working Class Woman living in Australia it reminds of how history is what we are and how important it is to our destiny. Your words energise and makes me think again about how history repeats such misery and it need not be that way. It’s vital to organise and speak truth to power. Back to the importance of reading and the power of language. Thanks again for a wonderful piece and it will inspire me to do the work for it’s the only path to real freedom.

Thanks Fay for your kind comment, and for sharing your insight.

Sometimes words are so heavy. Yet reading and resistance go hand in hand, and crucial, I think, in this disordered moment – one increasingly characterised by collective amnesia.

I am glad you celebrated Ferguson. He preferred republics to monarchies. Perhaps it is time for Edinburgh and Glasgow to rename their George Squares and Hanover Streets. He had respect and appreciation for Native American societies before the savage genocide got properly underway. He showed up the foundation myths of societies and by implication of their religions. If he made wrong political choices the times were difficult. I can still rememember Marxist economist Joan Robinson going around in Chinese dress to celebrate the peaceful wonders of Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

I found this a thoroughly thought-provoking piece, Paul, combining as it did politics, paradox, poesy and didacticism. It is so easy to allow polemic to get into the way of a genuine concern for humanity; your essay managed to convey a sense of unbiased compassion. Thankyou.

Beautifully written. Thanks.