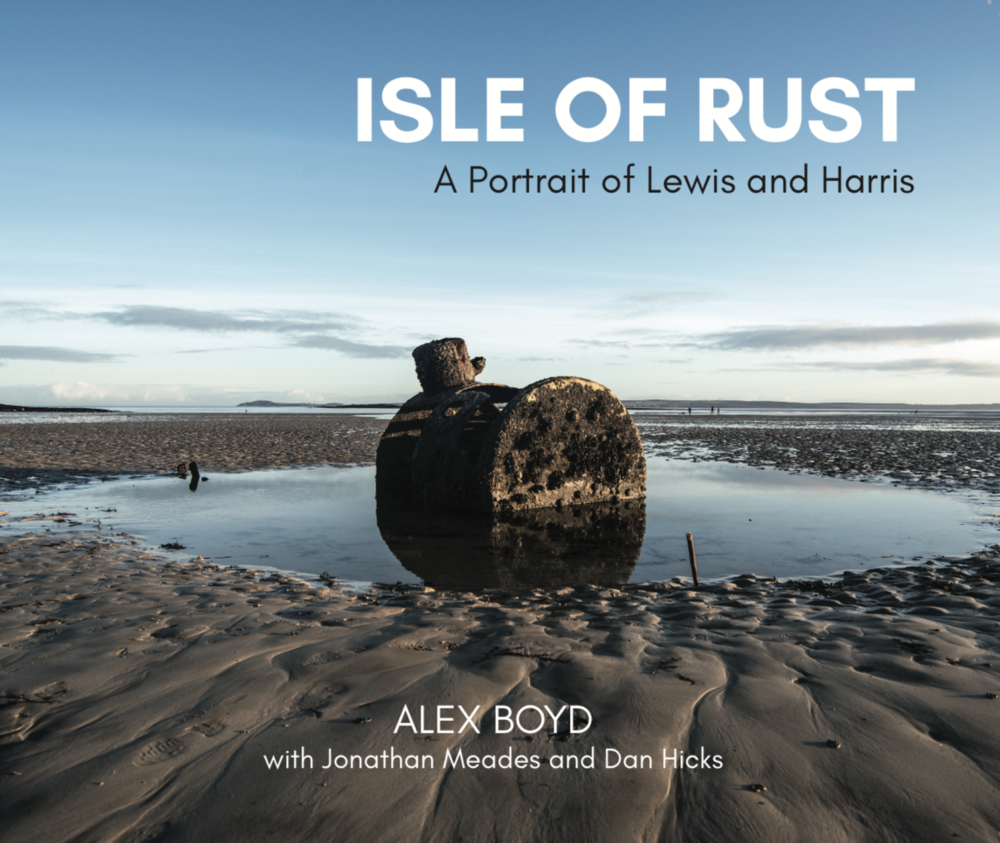

The Isle of Rust – a Portrait of Lewis and Harris

The Isle of Rust – a Portrait of Lewis and Harris by Alex Boyd, reviewed by John McDougall.

“Get through your first winter and you’ll be fine.”

This was the advice given time and time again to my parents after we moved to the North West Coast of Ireland in the early 1990s. We did, my parents and younger sister still live there to this day.

They’re still “Blow Ins” of course, each winter weathering them a little further. Each summer taking them a little closer to the landscape.

The seasons mould you on the Atlantic Coast. In these places of timelessness, stillness. These places which seem to operate at a different speed.

It is with the understanding that I view Alex Boyd’s latest photobook release “Isle of Rust”.

As Scots we innately understand the mythology and visual languages that have built up over the years placing anything an hour’s drive outside of the Central Belt as a romantic wilderness, devoid of people, untouched. We’re treated to golden sunsets over rugged hills and glorious sandy beaches which look like they’re straight out of some brochure for a balmy Caribbean island.

Perhaps as city dwellers many of us might even buy into it. Just ask the residents of Skye who are struggling under the weight of over tourism, the strains of heavy footfall on natural environments and the boom-bust economies that build up around seasonal visitors. Of course, Skye is more easily accessible than Lewis and Harris and as such it is less touched by those destructive hordes. In many ways, this only serves to heighten the romanticism an image heightened by the almost biblical status placed on Paul Strand’s 1962 survey of the Hebridean islands “Tir a’Mhurian” by photographers, artists and a certain breed of cultural historian.

Isle of Rust seeks to realign this imagery in some way. Boyd’s own “Three Winters and Two Summers” spent on the Island by no means make him a local, but they were enough to give him enough insight to create a portrait of the island which offers something different.

What we are presented with feels like a walk through the Island. At times a trudge. Heavy, boggy land beneath our feet. Wide open spaces offering views of enclosing weather systems grey, wet and unwelcoming. In turn those clouds give way to moments of clarity, traditional beauty, a sense of relief in the short-lived light.

At first glance there is a feeling of abandonment. Ruined cottages and the carcasses of vehicles lie in the landscape, slowly eaten away by the elements. Cold war bunkers and relics of World War II outposts lie among the reeds, their concrete presence jarring in their brutality yet somehow inadequate when placed alongside the Neolithic standing stones at Callanish. It is not abandonment Boyd is concerned with here but population, the movement of people and interests over time. There are people here now just as there were 5000 years ago. We see a smattering of portraits in the pages of this book, people carving their own notches into the land. Literally in most cases, as the peats cut from the island’s bog lands testify. More so in the case of Anne Campbell, the archaeologist and artist who Alex recounts as the person who welcomed him to the island in his foreword. There is much talk in this time of climate crisis about the Anthropocene. A geological notion of mankind’s mark on the make-up of the planet, a layer in amongst the strata of rock and sediment from which signs of human existence would be revealed long after our extinction. What we see through Boyd’s eyes is a further dissection of layer. The island’s unique landscape and geography allowing us an insight into how we shape the world around us.

Jonathan Meades’s essay from which the book takes its title is a caustic yet deeply thoughtful meditation on the duality of the Island. Its wildlife, brutal nature which can incapacitate the largest predators with the same substance it uses to feed its young. The visual imagery, on one hand glorious and untouched and promoted to tourists on the other barren and full of ancient tradition, also as promoted to tourists. The Island itself, two distinct lands Lewis and Harris. The relaxation and peace provided by an enforced religious sabbath which restricts all but the most basic of movement. Meades’ words provide a foil for Boyd’s images, for our journey with them around the island, setting up an irresistible collision between the historical possibilities contained and preserved within the island’s geography and what the future might look like, after humanity.

An afterword by Dan Hicks, Professor of Contemporary Archaeology ties the two together with suggestions of “visual archaeology”, “remoteness of time” and a mutual attention to the “detritus of human life”. Perhaps if we look at our rural and remote areas through these kinds of ideas, we might find ourselves falling less into the trap of tartan and bagpipes and begin to understand our country, and out cultures with more conviction.

Isle of Rust is a work which, despite its use of colour, sits well beside Boyd’s Saltire Award nominated debut “St Kilda: The Silent Islands”. Together they provide an alternate look at two of the most mythologised areas of Scotland.

On it’s own, Isle of Rust is an affectionate but by no means nostalgic or romanticised view of one of Europe’s furthest edges.

These rusting artefacts are sign of how unclosed and degenerative modern human culture is? As opposed to:

https://www.kateraworth.com/2017/04/16/spring-renewal-bring-on-regenerative-economics/

What would images of a regenerative culture look like? Possibly more like a healthy ecosystem.

Areas of low population density, and economic poverty, leave abandoned vehicle carcasses to rust around the globe – not just here. The feeling of wilderness and abandonment in the Hebrides is considerable, and to some extent that is because it is harsh and unwelcoming land, and is also because structural poverty is a consequence of the long-term politics and struggle of an impoverished Scotland.