Many Voices Q&A with Sekai Machache

As part of her Many Voices project, Arusa Qureshi speaks to industry figures in Scotland to hear their thoughts on diversity and the inclusion of underrepresented voices in their respective fields.

With an abundance of world-class galleries and prestigious institutions, Scotland is a hotbed for innovation and talent within the visual arts. From Charlotte Prodger’s Turner Prize win in 2018 to artist, researcher and curator Alberta Whittle recently being announced as this year’s recipient of the annual Frieze Artist Award, there’s plenty to celebrate and be proud of across disciplines. Among the many artists that are currently making work in Scotland that is both cutting edge and profoundly creative is visual artist and curator Sekai Machache and like others, she is being internationally recognised for that creativity. As a graduate of DJCAD, Sekai works in a multi-disciplinary practice and with a wide range of media, with recent work being exhibited at Stills: Centre for Photography in Edinburgh and due to feature at Glasgow’s Street Level Photoworks.

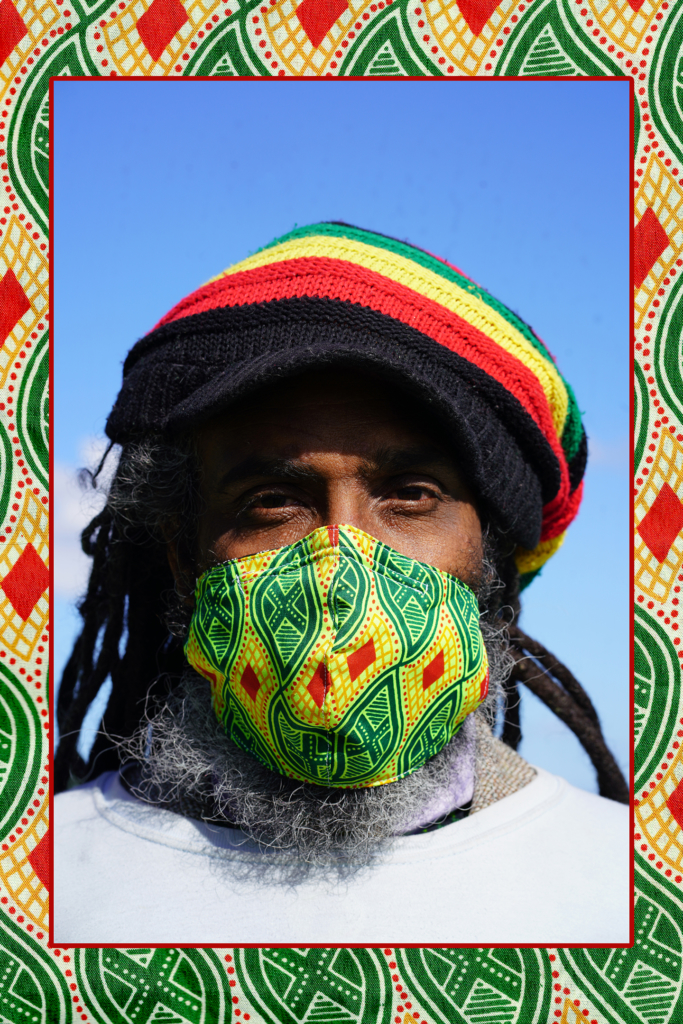

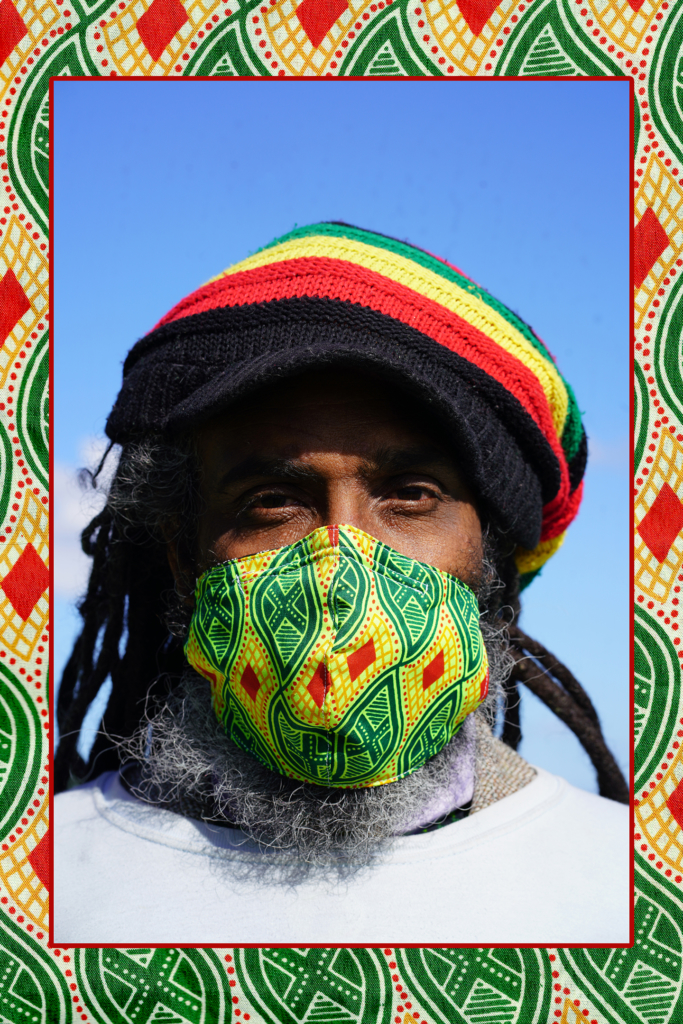

Over the summer, Sekai was invited to take part in the Scottish Black Lives Matter Mural Trail, which was organised by Edinburgh-based creative producer Wezi Mhura in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. The trail features powerful artworks by Scottish Black and Asian artists which have popped up on multiple venues and sites in towns and cities across Scotland. Sekai’s contribution in Dundee’s Slessor Gardens – called a BREAdTH apart – includes 16 portraits of black people in Scotland wearing facemasks made of stunning African cloth. Unfortunately, earlier this month, Sekai’s images were torn down in an act of racist vandalism which came after a mural of George Floyd in Dundee was also defaced. As well as being a hugely disappointing turn of events, the incident highlights exactly why conversation is needed to properly interrogate Scotland’s attitudes to race and racism. In this Q&A, conducted before the incident took place, Sekai speaks more about her involvement in the Mural Trail and what she believes is needed to support artists of colour in years to come.

Can you tell me a little more about the Black Lives Matter Mural Trail and how you got involved with this project?

The BLM Mural Trail was produced by Wezi Mhura earlier this year in response to the BLM protests that were taking place globally and to raise awareness of the need for us to discuss racism and anti-blackness in Scotland. Wezi contacted me fairly early on and asked me if I’d be interested in creating a mural in Dundee as I had been living there at the time. I thought it was important to participate in this project as a Black person living in Scotland and as an artist who frequently discusses racism and the psychological effects of anti-blackness in my work. I remember at the time feeling that it was important to point out the longevity of the BLM movement as many people were acting like it was all brand new and were discussing the movement as a ‘moment’.

Wezi was being approached by a number of organisations across the country to develop the project and she contacted me a few weeks later to let me know that she had partnered up with Dundee based project Sharing Not Hoarding who run public art spaces in the city. They have this space at Slessor Gardens next to the Waterfront Development, with 18 billboards and we were basically able to fill them with images which was great because it felt a lot more plausible for me to contribute as a photographer.

A few weeks later there was a Black Lives Matter protest in Dundee, so I took a good number of the photos there. I decided to collaborate with artist and textiles designer, Fiona Powell who made the face masks for the project. I gave some African-style fabric that I’d collected over the years and she made a series of really beautiful bespoke masks. Her design is quite unique as she made the masks double sided and they have a drawstring toggle that helps you to put them on so that they fit really well on your face. I was really happy with the design and would definitely recommend anyone that is looking for stylish face masks to look her up.

When you entered the industry in Scotland, did you feel as if there was a space here for you? How did this affect your work and your practice?

I think back to my mindset when I started at art school and I was quite naive because I’d been raised in a predominantly white area with a white family. So, I’d been in the space of assimilating for such a long time that I just didn’t see myself as different. I thought I was the same as everyone else. I experienced racism; obviously, I experienced microaggressions constantly, but I didn’t have a name for that kind of constant level of racism that’s just perpetuated all day, every day. I just knew what it felt like to be that person that was always treated differently but strived to be considered the same as everyone else.

When I went to art school, I honestly thought it would be the most liberating place in the world. Obviously, that’s just not what art school is like in reality. When I went there, I wasn’t really thinking about race. I’m interested in psychology and think a lot about how the mind works and ideas around consciousness so naturally I was making art about that. I was keeping dream journals and making art projects that were based on my experiences of having intense sleep problems like insomnia and sleep paralysis. When I took photographs or made work with a white figure in them, people totally got it and its connection to the themes I just mentioned. And then when I would take a photograph of myself, it would always become about race. But that’s not what I was talking about, that’s not what I was thinking about. And then quite quickly, because of these misinterpretations of the work, I started to look at other Black artists. I remember looking at Kerry James Marshall, and he talked about how he made the decision really early on in life that he was never going to draw a white figure ever again. So, his work was going to be specifically Black figures and it was because he thought that it was important for Black bodies to be able to ‘convey universal human experiences.’

I remember reading that and understanding that I had to make a decision about how I was going to tackle this misinterpretation of my work. I decided to tackle it by doing a lot of research into why this was happening, so I started to learn about the White gaze and how White institutions and structures create a narrative about marginalised artists and how many artists of colour are Othered. So, if you’re queer, if you’re a person of colour, if you’re disabled, you’re not just an artist. You’re a disabled artist, a queer artist, a Black artist etc. So that was something that became massive for me and since 2012, when I graduated from undergrad, I guess it’s been one of the main themes that underpin my practice. I still make a lot of work about the things I’m actually interested in, but I do it with that understanding of how they will be perceived through the White gaze. It’s not my central focus, but just an aspect of my practice that I and other artists like myself have yet to be liberated from.

Do you think there’s a pressure for artists of colour to make work that deals directly with the experience of race and racism? And if so, is that a hindrance in terms of progression in the art world?

It’s hard to just focus on Scotland because this is a global issue. Artists of colour don’t get to just be artists, period. Not because Scotland particularly has this problem, because the world has this problem. However, when you look at Scotland’s history specifically, you start to understand that a little bit of the impetus in not engaging with conversation around race and racism is that Scotland has been in many ways trying to obscure its ties to colonialism and slavery for such a long time that it doesn’t want to touch those subjects. So, when we as Scottish artists of colour come along and start talking about these things and saying this is unfair, the reaction is usually “What do you mean? We don’t have a problem with racism.” And then you’re tackling that cognitive dissonance and the selective amnesia that Scotland has as a nation on top of the difficulty of trying to make work as an artist of colour.

How open do you feel the Scottish creative industries are in terms of discussions of diversity, equality and anti-racist work?

In my experience, they like to talk about it in a sort of performative manner. All organisations right now are talking about EDI or they’re talking about how they can improve diversity or make their spaces more inclusive. It feels like there has been a lot of talking and not enough action, although I do see it happening slowly but surely. I’ve found that there are people who are in really high up positions in really important organisations who work in EDI, and they don’t even know the demographics of their own organisations. I always wonder how they expect things to change within the wider sector if they haven’t even resolved the issue within their own working environment. Sadly, in my experience, even when you do have a good connection with an institution that you’re working with, it’s always a little bit shaky. You never know if tomorrow they might just randomly say something or do something that completely changes the dynamic. So, I do find myself constantly aware that I can’t ever feel too comfortable.

Many promises and pledges have been made by institutions in response to Black Lives Matter but do you feel as if real action has taken place?

I think the problem is that when they do actually take action, it’s always kind of quite piecemeal. I feel as if institutions sometimes have their one Black person or their one or two people of colour that they always go to speak on issues of race. I’m constantly giving people lists. That’s what I do now with organisations that are asking me to speak on this issue a little too often. I give them a list of artists and creatives that they can contact instead so that I know they have that list for future conversations on the topic. I don’t want to be a token and I think there are plenty of other incredible artists who are often overlooked because institutions feel comfortable with the people they already know.

One reason individuals don’t pursue such an industry is because they don’t see people of colour in senior/management positions and don’t feel as if they could ever be in those positions as a result. What’s your opinion on this? Is it a concern you share?

I think representation is a massive, massive problem, in all areas of organisations. I always feel that the solutions are quite simple though. All they need to do is actively engage the communities that are under-represented, offer training, mentorship and opportunities to enter the sector and not just once. They need to make it a priority to change the demographics until a real shift happens. There needs to be consistency and dedication to changing the status quo.

That’s what I think would work because that’s what works for me. If I have access, I try to bring other people with me. And that’s what a lot of us do.

Depending on the project, depending on what’s necessary I think that sometimes people who run institutions act as if we’re being nepotistic to each other. But the reality of the situation is we know who’s good at what and we ask, nominate, offer opportunities to each other because we are aware of each other. They are not aware of us and that’s the issue. They don’t know who the best people are at these things and that’s a failure, I think, of the institution. The situation isn’t dire though, it is improving in places.

If you could have one thing change in terms of your field in the arts in Scotland in the next few years, what would that be?

I think people have to figure out a way for things to still be sustainable. So, if you move everything into the digital space, people will just slowly stop being paid. And then there’s all of those jobs that require people to physically be there, that aren’t also being thought about. I think it’s a tough question because no one knows what’s going to happen next. There’s this whole impending doom of another economic recession and the dreaded Brexit looming. It can feel as though institutions are basically more concerned about saving their own neck than they are about what happens to the whole industry, and the people that are making all the work.

In terms of workload with people being made redundant and teams becoming smaller, it’s unsustainable. People are going to burn out, people are going to get sick. It’s going to be difficult to sustain these spaces and I think we all need to prepare ourselves for that. I do feel optimistic in some ways though because I think some of the important conversations are happening and this may steer us in the right direction.

What can be done to get more creatives of colour involved in the arts in Scotland in a way that is genuine and not tokenistic, with attention also given to sustained support?

A dream of mine would be to actually just create a space or multiple spaces for training and for mentorship that literally help to put people on their chosen path. Because in these institutions, like the art schools, these young people of colour are going in there and they’re being fed to the wolves. They don’t know necessarily what is going to happen to them once they walk into these spaces, whether it’s the art school or the conservatoire and they’re doing a hell of a great job of tackling that. I’ve noticed that in the last couple of years, people are just not taking it lying down anymore and they’re taking on the institutions and forcing them to look at how they treat us. However, they also need to know that the people who have come before them are here and we’re ready to mentor and guide and be there for them. So, if we could create spaces where that could happen easily, that would be amazing. I guess the other thing would be proper training for people within the institutions and organisations and follow through. There’s no point in getting trained and then still doing nothing about it.

Image credits from the BLM Mural Trail are by Sekai Machache. Her Instagram handle is @sekaimachache.

The images of the reinstalled Mural Trail at Slessor Gardens in Dundee were taken by artist Janice Aitken @janice_aitken