UncoverEd and the Decolonisation of Edinburgh University

Launched in 2018, UncoverEd is a unique archival project based at the University of Edinburgh, aiming at uncovering the stories of alumni of colour who studied at the university from the early 19th century through to the present day (“ a collaborative student-led archival project to discover and publish the stories of our BAME and international alumni since the University was founded”). With an exhibition, numerous talks, and an ever-growing timeline under its belt, UncoverEd works to fill in the silences and gaps that have long been allowed to widen under the colonial structures that created and define the university. In this interview, we speak to one of the project’s current co-ordinators Hannah McGurk about these alumni’s stories, what changes such projects can make, and whether it is possible to decolonise an existing university.

AB: I was wondering if you could start off by telling me about how UncoverEd came to be?

HM: It started with James Smith the Vice President International [at the University of Edinburgh]. He was looking into the first African students at the University – it was his own passion project. And then he decided to get proper funding and […] hire a team of students to help with archival research and broaden it out from Africa to students from Asia and ex-colonies. [We] wanted to make it critical and talk about the colonial and imperial links, and how and why students were coming. So that was September 2018, and we did that big block of research with an exhibition.

AB: What was the exhibition?

HM: It was in the Crystal Macmillan building [at the University of Edinburgh]. That was always what it was gearing up to, that’s why we were hired. It was to talk about Edinburgh in a global international sense, but also what that means when you talk about it in an imperial context.

AB: You’re finding all these people in the archives who have been silenced or ignored. What is your particular focus: is it about discovering their stories, or about the link to the university, or something else?

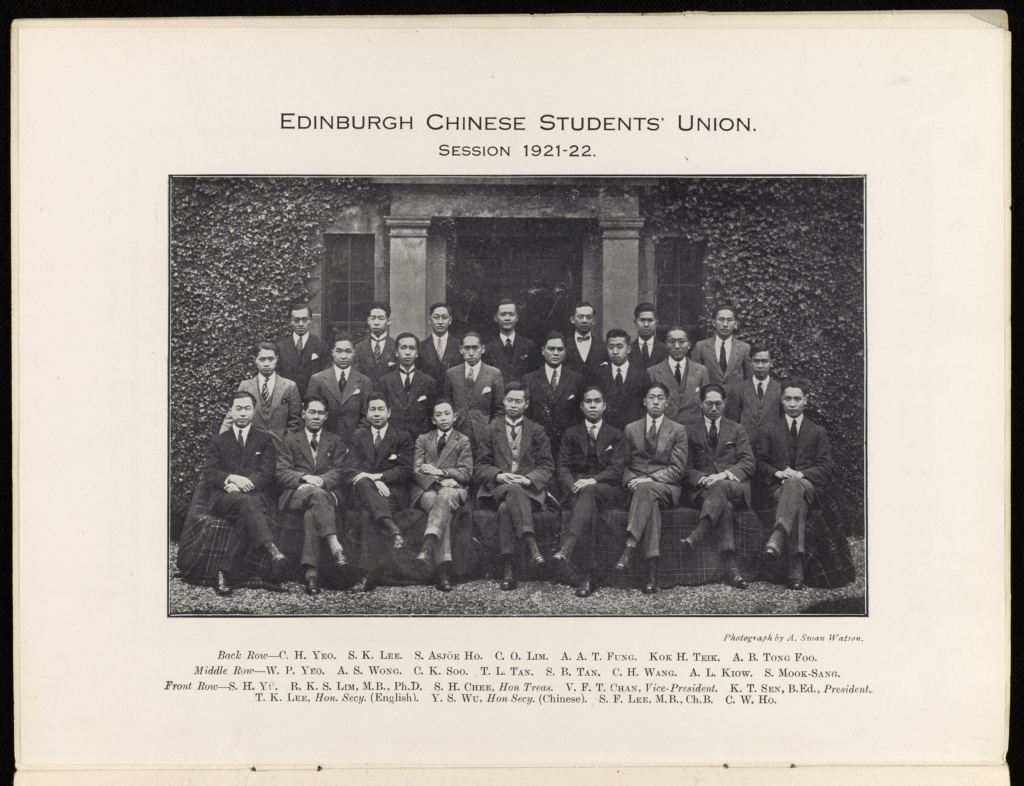

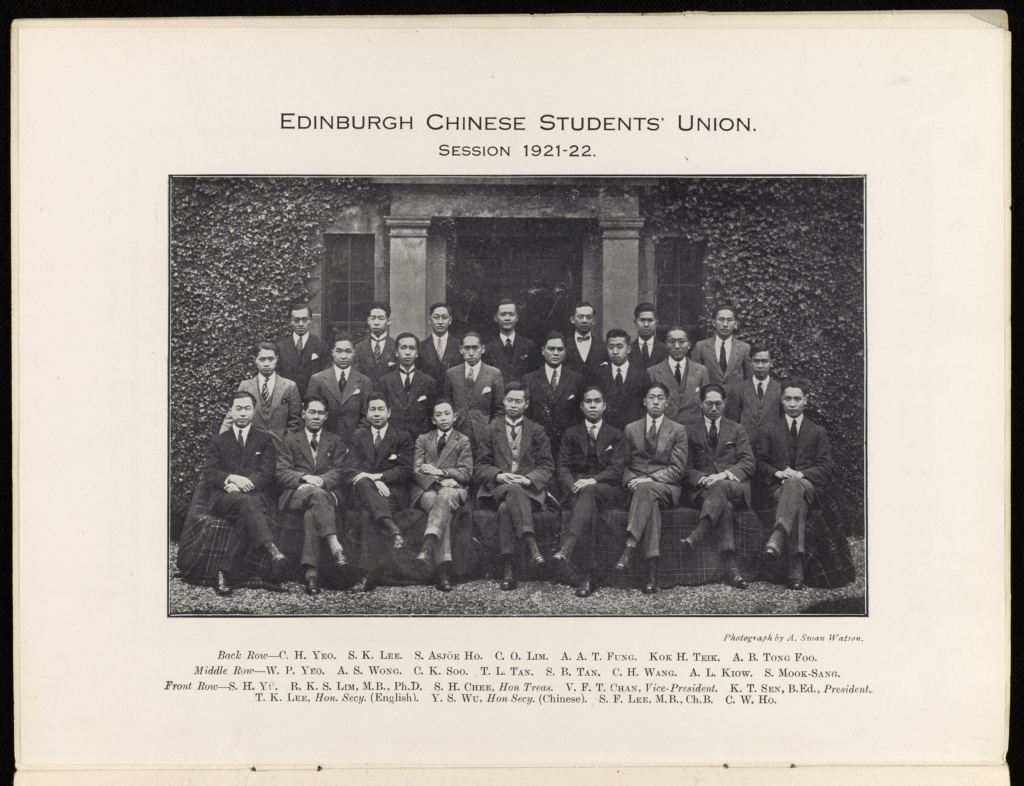

HM: Our first block of research was about the people and their experiences and who we could find in the archives through the student newspapers. Looking at their lives and [asking] what was Edinburgh the site of throughout those two or three hundred years? In 1900, there was a cohort of African students who went to the pan-African conference in London from Edinburgh, and student associations were cropping up in the late 1880s: the Indian Students Association and the Chinese Students Association, and the Caribbean Students Association in the early 20th century. We wanted to talk about what they took from Edinburgh and what Edinburgh gave to them, but also what Edinburgh took away.

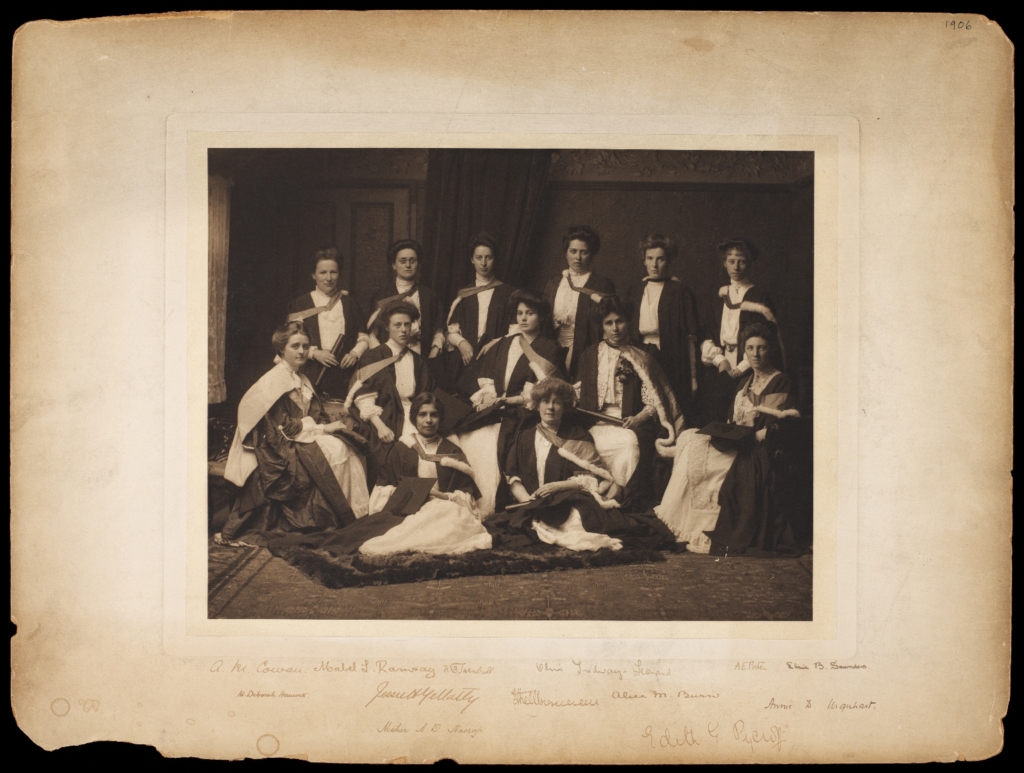

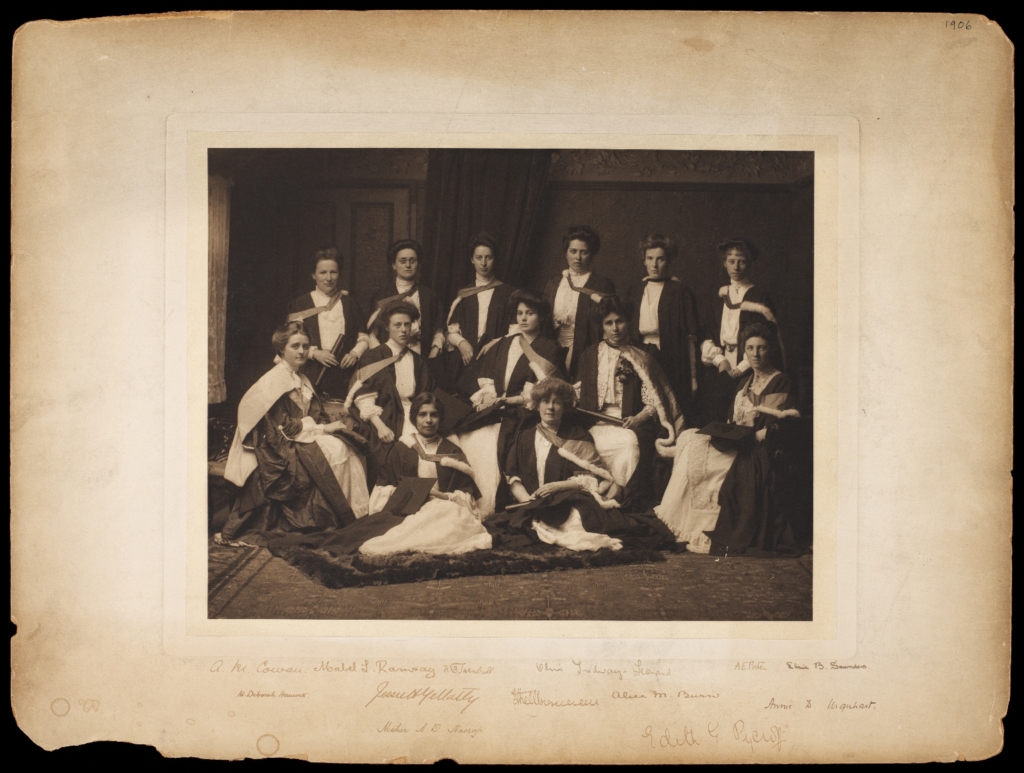

Meher Naoroji, Women MBChB Candidates – photo courtesy of Edinburgh University

AB: You mentioned what Edinburgh both gives and takes away, and I’m really interested in that.

HM: It’s in lots of different ways. There’s the intellectual, academic side of it. A lot of eugenics and phrenology can be traced back to scientists at Edinburgh. But also anthropology, and the way we understand race relations today came from Edinburgh academics. So what was intellectual production at the time? And how were those students participating in it? How much were they case studies for those things?

And then also socially. How did [the university] provide community? How did they build communities themselves? And in what ways were they forced to or in what ways was it an act of resistance? Because there was hostility: there was a colour bar in the early 1920s, […] and there’s a report of a Jamaican student getting attacked on the Meadows, coming back from playing dominoes.

AB: I was looking at the timeline earlier, and it’s really interesting to see how history shifts through the 19th and 20th centuries – like the introduction of differential fees for “foreign” students in the 1960s – in ways that continues to other them.

HM: For sure. The archives itself is great evidence. There would be lists – “we have 20 students from China this year, and like, x students from this country” – but nobody’s names, and they’re not recorded in the same way as white Scottish students were. So it starts at that level. Or there might be a student from South Africa, and you don’t know if that’s a white student, or a Black or Indian student. There are subtle ways that it would be coded throughout the archive.

What I would still like to look at more is when domestic students who weren’t white started coming to university. But that is also a bit complicated, because you look at someone like Agnes Yewande Savage, who was a student in the 1920s. Her mother was a white Scottish woman, so she was born here. And she studied as a doctor and then went to her father’s country [in Nigeria] to work as a doctor, but she was treated like one of the servants. So that’s a really complicated dynamic: she’s not counted as British in these contexts, and wasn’t counted as being a doctor in other contexts. But, technically, she would have been one of the first black British students.

Matilda J Clerk – Courtesy of University of Edinburgh

AB: Why for you, is it so important to uncover these stories?

HM: I think it’s about understanding how Edinburgh operates: how the university operates within the city, how it affects people’s lives, and how it treats people. I definitely want to open it out to more than just alumni. To me, that’s not super meaningful. I think you have to talk about the communities around Edinburgh. But I think it’s [also] about contextualising Edinburgh’s history and being more honest about when you call Edinburgh a global university. What does that really mean? To me, it’s not necessarily about people’s individual narratives, it’s the structures, how they began and how they were perpetuated and how they still affect students today.

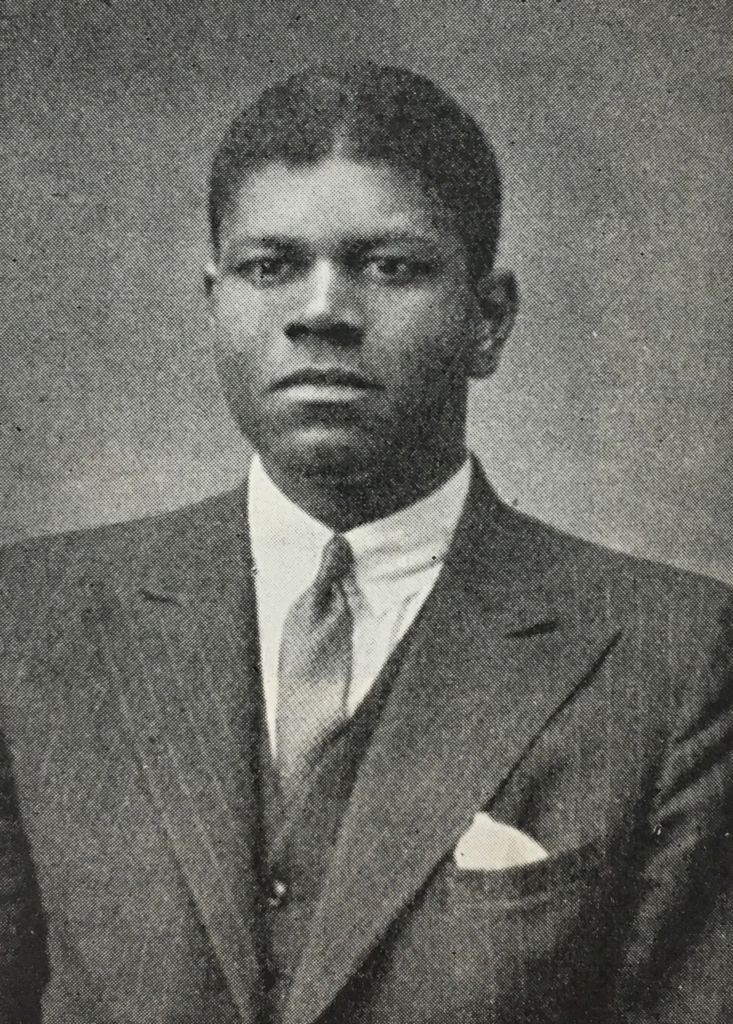

David Pitt – photo courtesy of Edinburgh University

AB: When you say you’d like to open it up, what would that maybe look like?

HM: Definitely doing more community outreach, getting away from the University archives as a start, into the city’s archives. There are people like Lisa Williams, who I really admire, she’s done so much research independently, and also gives it back simultaneously. And the process that I want to be involved in more, that community outreach and getting other people to take ownership of these stories.

AB: What is it about the Scottish context that is specific to the work you do?

HM: It’s definitely about confronting that Scottish narrative of, “we weren’t that bad, this wasn’t really our problem, we weren’t involved”. We came up against that quite a lot right at the beginning. I think that’s where the uncovering part of it comes from, there is an extra layer of “this wasn’t us” that you have to get past. It’s embedded in everything, the buildings and architecture. Visually, you can see it and feel it. You do have to get past that extra stuff.

AB: What have been some of the responses from the academy?

HM: People have been largely positive and encouraging, and they like the project. But I think that’s also what makes me be like, we’re not doing our job. I think people are very happy to be like, “oh, these are the Black faces of Edinburgh”, right? “Yes, this is part of us and this is our history, hurray”. It’s getting them to be more self-critical and reflective. In terms of the tensions within the project, we’ve been talking about decolonisation a lot, and whether that’s really a word that we should use.

AB: Can you tell me more about that?

HB: It’s just, being so embedded in the university and being funded by the university. It’s like what we were saying about these individual narratives, to what extent can you call that decolonial? But also, it doesn’t have to be decolonial to be meaningful. And so that’s where we are right now. The university is what it is, we’re not fundamentally going to change the structures – maybe that’s not our job – but we can speak to people’s experiences and open the idea of community.

AB: So is it that you don’t think this project is pushing enough for that decolonial work? Or is it more that you think that is just not compatible with the idea of a university?

HM: I think it’s not compatible with the university. Decolonisation has to be material and it has to start returning something to someone and I think that’s just not what we’re doing.

AB: Do you think it is possible then to decolonise the university?

HM: I don’t know if it is possible to decolonise an existing university, especially not one with as long history as Edinburgh. But I think you could start a new university that is genuinely collaborative and free and open access.

AB: Okay. So what is it that you hope this project does? Because I completely agree with you, but I’m interested in how these projects have space and value? Or do you think that they are maybe distractions from the proper work?

HM: Well, my hope is that something like UncoverEd informs the work that people are doing on the ground. I wrote a piece about the experiences of Caribbean students, and it just parallels so much of my experience, and also the existence of the African-Caribbean Society here. I hope that groups like that can use our research and use that evidence to make their own case, and be able to go to the University and demand things based on this historical lack.

AB: Who is one of the most memorable people that you have discovered?

HM: I’m really interested in a lot of the early art students, who I think would have been going against their family’s wishes to come and like, study sculpture. Natasha Ruwona [McGurk’s fellow project co-ordinator] has been working on some of these students, and they’re the ones who speak to me the most. As much as I admire the medical students, I just think the arts students are cool.

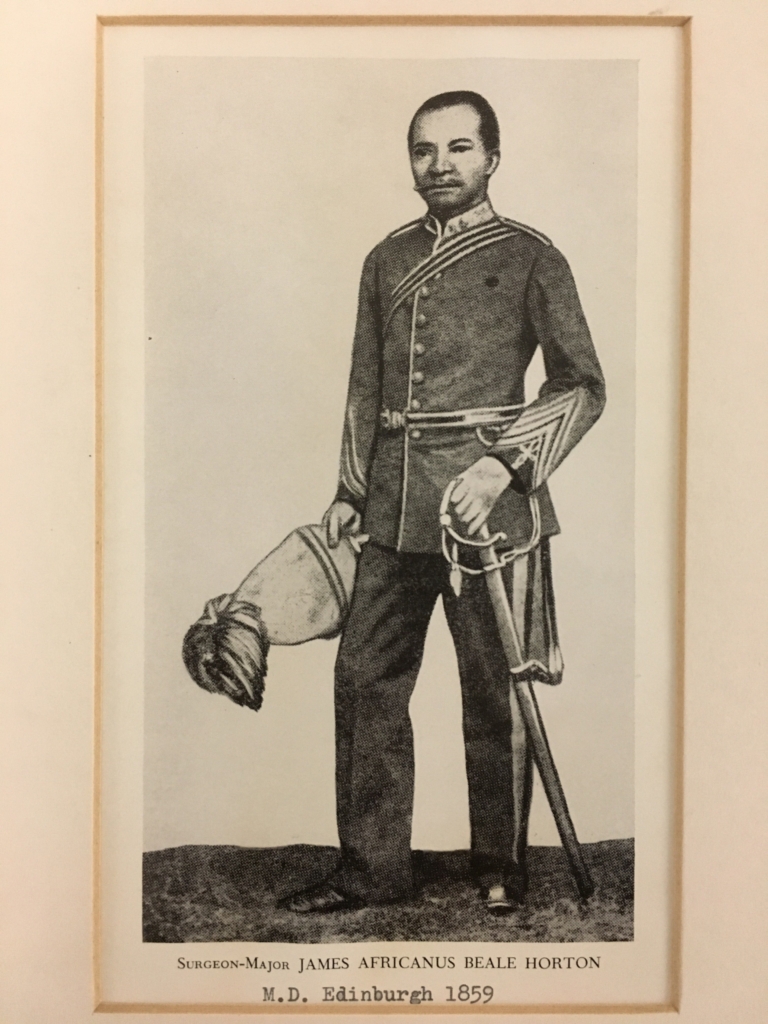

AB: That was something that was really interesting to me, how many medical students there were. Do you know why?

HM: It was that the medical school was actively recruiting, and I think they were one of the earliest to, so that’s why Edinburgh got this status so early on where Oxford and Cambridge didn’t. Because every plantation needed doctors: there were a lot of Scottish doctors, but they were dying really young, and so it became about recruiting people from those places.

AB: In the stuff that you’ve discovered, has there been anything about people’s affective relationship with that? About going back to do the work of the colonies?

HM: It [was largely] more factual. [But] there is that thing of people coming and then learning about colonialism and imperialism, and being like, “oh, shit, this is what’s going on in my country”. One thing I found really hard to read was in The Student, they would have records of the debates going on. And it was usually, “oh, the colonies are a problem, what do we do about this”. You can just picture it.

AB: Yeah. Big Oxford Union vibes.

HM: Exactly. And just knowing that those students were also there, watching people talk about their country as a nuisance. Which I feel still happens today. You do see those kind of tensions.

Discover more about UncoverEd do here.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The manuscript of Julius Nyerere’s Swahili translation of Shakespeare’s JULIUS CAESAR is in Special Collections in the University Library. I worked there in the early 1980s. Nyerere took his PhD at Edinburgh.

There is also a period during which the children of dictators (typically those in the neocolonial stage of empire) were being sent to study in British institutions, their parents not fearing that they would pick up any nasty democratic leanings at these fine establishments (later somewhat overshadowed by USAmerican ones). I am not sure if Edinburgh University would have featured on this list or not. I suppose the modern trend has been children of Russian oligarchs, but they are presumably well aware of this tradition. This article has some nice examples, but there is nothing preventing a medical student becoming a dictator when they get back home.

The last leader whose regime legalised slavery in the British Empire was, I believe, until his death in 1970 the Sultan of Oman:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qaboos_bin_Said#Early_life_and_education

educated at private school in Bury St Edmunds, later Sandhurst.

I have had a quick look at the Uncover-Ed site, and am not sure if its tone would accommodate people who were a bit more controversial or actively participated in colonial or neocolonial oppression. However, if Edinburgh University was one of the institutions dictators would not send their children to (or attend themselves), does this mean that there was division, dissent and contention between universities on the subject of British colonialism? I have gathered that some of the non-conformist institutions set themselves up in ideological opposition to imperial colleges, but I am not aware of any historical anti-imperial stances amongst the Russell Group.