The Coronation Chicken will Not Be Chlorinated

As Nigel Farage launches yet another party, it’s worth reflecting on the make-up of the populist movement that leads Britain’s Left Behind. Brexit [we’re constantly told] is the manifestation of long pent-up frustrations, alienation and disempowerment. But it turns out Britain’s Rust Belt is more of a Cumberbund. The revolution by the oppressed Northern Hordes are to be led by none other than Annunziata Rees-Mogg the daughter of Sir William Rees-Mogg (knighted editor of Times) and the Deputy Editor of MoneyWeek (where she works with the awesome Merryn Somerset Webb).

Take that you out of touch metroplitan elites.

Farage’s “Brexit Party” was given the predictable wall to wall media coverage – BBC News and Sky News coughed up unquestioning live national reporting to this brand new party and seemed to dodge his inflammatory language:

“We can again start to put the fear of God into our MPs – they deserve nothing less after the way they treated us.”

As the febrile atmosphere of English constitutional politics becomes more splintered and toxic, some have even suggested that the monarchy could be a moderating influence. I’m not sure how having Prince Philip involved would reduce mounting racial tensions and the rise of far-right ideas, but it’s a nice thought.

But as May’s regime enters a new liminal space of endless flextension and the constitutional crisis rumbles on, it’s worth looking at other parallel timelines:

1. The Queen is 92 and although she’s had the most precious life in the world she will at some point – sooner or later – die. That event is likely to trigger the already unsettled Blue Rinse Patriots from their slumbers. Charles and Camilla are not well liked. Attempts to re-boot the franchise with young pregnant royals has stalled on the opportunism and implicit racism of British tabloid culture. The Diana Cult will be revived.

The vagaries of having your head of state come from one dysfunctional gene pool may not survive the transition. If ever there was a time to add meaning to the “take back control” slogan, this would be it.

2. These recalcitrant Jocks won’t wait forever. The SNP conference is 27th & 28th April 2019, and something’s got to give.

3. The European Parliament election, 2019 will begin on Thursday 23 May, and ends on Sunday, 26 May. They may be filled with virulent anti-EU candidates or loyal Remainers, Greens and Liberals. The paradox is that the issue to which we are apparently transfixed will evoke a very small turnout. This is an opportunity for progressive and radical forces (however you want to define them).

4. A climate crisis very hot summer – is soon to be upon us. What happens when urban unrest meets “betrayal” in Tommy’s Brexitland? Lager lager lager.

5. The arrival of a “true Brexiteer” to save the process and replace Theresa May. Timing unknown.

This might be fine. They might usher in Boris and join the two wings in matrimony over a new Royal Yacht or some Millennium Dome-style distraction project. But there are dangers in this. They have kept the crazier Tories locked in the attic till now, havering away in the ERG or going rogue in Tel Aviv, but it may prove impossible to keep all the plates in the air if they escape down into the public rooms. Colonel Ruth for one will be disappointed.

All of this has been predicted for a long time, as Tom Nairn wrote only in 1977:

“There is no doubt that the old British state is going down. But, so far at least, it has been a slow foundering rather than the Titanic-type disaster so often predicted. And in the 1970s it has begun to assume a form which practically no one foresaw. Prophets of doom always focused, quite understandably, upon social and economic factors. Blatant, deliberately preserved inequities of class were the striking feature of the English social order. Here was the original proletariat of the world’s industrial revolution, still concentrated in huge depressed urban areas, still conscious of being a class—capable of being moved to revolutionary action, surely, when the economic crisis got bad enough. As for the economic slide itself, nothing seemed more certain. A constantly weakening industrial base, a dominant financial sector oriented towards foreign investment rather than the re-structuring of British industries, a non-technocratic state quite unable to bring about the ‘revolution from above’ needed to redress this balance: everything conspired to cause an inexorable spiral of decline. The slide would end in break-down, sooner rather than later.

Clearly the prophecies were out of focus, in spite of the strong elements of truth in them. The way things have actually gone poses two related questions. Firstly, why has the old British state-system lasted so long, in the face of such continuous decline and adversity? Secondly, why has the break-down begun to occur in the form of territorial disintegration, rather than as the long-awaited social revolution? Why has the threat of secession apparently eclipsed that of the class struggle, in the 1970s?”

Even Nairn couldn’t have predicted how rapid the national forces within the ‘UK’ would become central:

“There were episodes of conquest in the histories of northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland, true enough. But these had been followed or accompanied by episodes of assimilation and voluntary integration—and until the 1960s it looked as if the latter tendencies had triumphed. All three societies had, at least in part, crossed over the main divide of the development process. Unlike southern Ireland, they had become significantly industrialized in the course of the nineteenth century. All three had turned into important sub-centres of the Victorian capitalist economy, and around their great urban centres—Belfast, Cardiff and Glasgow—had evolved middle and working classes who, consciously and indisputably, gave their primary political allegiance to the imperial state. Through this allegiance they became subjects of one of the great unitary states of history. Absorption, not federation, had always been the principle of its development.”

But absorption has failed and Belfast Cardiff and Glasgow aren’t onside any more.

Second the extent to which Nairn anticipates and articulates the double-bind of English nationalism as put out today by such writers as Anthony Barnett and Gareth Young is prescient:

“The paralytic decline of the old state has given a temporary ascendancy to Scotland and other peripheric problems. Beyond this moment, it is bound to be the post-imperial crisis of the English people itself which takes over—the crisis so long delayed by the combination of inner resilience and outward fortune we have discussed. However, this social crisis is rendered enigmatic by the cryptic nature of English nationalism. A peculiar repression and truncation of Englishness was inseparable from the structure of British imperialism, and this is one explanation of the salience of racism in recent English politics. The growth of a far Right axed on questions of race and immigration is in fact a comment on the absence of a normal nationalist sentiment, rather than an expression of nationalism.”

This is still true, and writers who try and explore the nature of Anglo-British nationalism should remember it.

But the forces – and resources – swirling around the UK’s right and far-right in its various new guises are operating in historically unique circumstances in which the British political system is broken and facing threats on several (Celtic) fronts, a disoriented and splintered opposition party and Brexit-inspired constitutional crisis. Fascism thrives on such crisis, and it’s into this atmosphere that the death of the monarch would land, adding a new dimension.

We should consider that civil unrest and repression isn’t unlikely given the opposing forces and tensions that are at play. We know that Boris Johnson as London Mayor had no hesitation in buying water cannon from German police back in 2014 in anticipation of uprisings, even if that ended in humiliation.

But if we’re in any doubt that the possibility of (genuine) civil unrest and (genuine) elite repression isn’t a possibility we should remember the wonderful Eton entrance exam questions of 2011:

“Twenty-five protesters have been killed by the Army. You are the Prime Minister. Explain why employing the Army against violent protesters was the only option available to you and one which was both necessary and moral.”

Potential Etonians had to write a script for a TV broadcast in which they defended the killing of 25 protesters by the Army after sending in the troops to quell protests. They had to say why the decision was both “necessary” and “moral” in the wake of the protesters killing police officers as they ransacked public buildings after an oil crisis in the Middle East led to the UK running out of petrol.

The final element of the British crisis – and the instability that puts us in potentially dangerous times – is not the cartoonish Tommy Robinson and Nigel Farage and Annunziata Rees-Mogg – it is the fragility of the Tory party itself.

As

“Where today’s Labour party boasts half a million members, there are fewer card-carrying Tories than Mormons in the UK. What’s more, according to research from the London School of Economics, the party was reliant over the past decade on just 15 sources for almost a third of its entire income. The atrophying of Tory democracy has turned the party into a leisure pursuit for the tinhat brigade and a gewgaw for multimillionaires.”

The Conservative Party and Conservative England is a dying animal. It’s dying of its own absurdities and contradictions and because it has run out of victims to blame. But Britain cannot be held together by bunting alone.

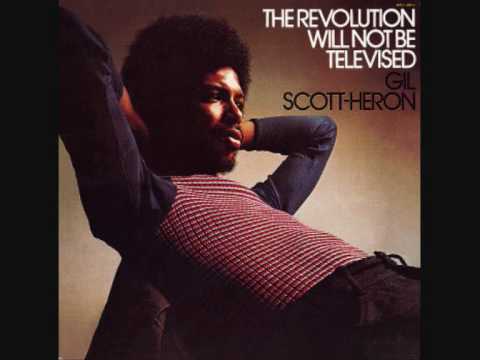

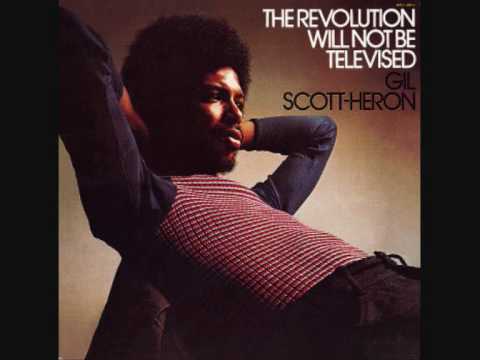

On Charles’s coronation remember that Gil Scott Heron’s A side to the Revolution Will Not Be Televised was Home Is Where the Hatred Is.

We in England have already received our voting cards for the 3 May Local Elections.

The results need of these will need to be factored in too, with regard to the above excellent analysis.

Tros Gymru / For Scotland.

Use real name Yaxley Lennon if at all.