IWGB Couriers: Organising in the Gig Economy

The gig economy is the perfect amalgamation of the threats to worker rights in the twenty-first century. Flexible hours and flashy apps serve to mask the evisceration of collective bargaining and the rise of algorithmically determined working conditions that evade regulation. Dolly Parton’s famous song, “9 to 5”, has been replaced by the infamous “5 to 9” – a culture that glorifies side gigs as an exercise in individual agency rather than as a growing industry through which workers increasingly make not-quite-a-living. Couriers have become emblematic of these conditions.

Martin became a Deliveroo rider in the autumn of 2019 because of how the company marketed itself to students; he says he was attracted to the idea of a flexible job where he had control over how many hours he worked and how much money he made. He joined the IWGB Couriers immediately, before even realising just how necessary the campaign was.

He soon realised that this industry is not, in fact, primarily a place for young people to earn some extra cash. He explains that companies like Deliveroo “take pride in the fact that they hire young people, and they don’t want to make it a full-time job. They want to show it as something flexible that you can just use to add to your income and then never really show the other side, which is middle-aged people who have to support their families and they can’t really with like the pay Deliveroo give them”. Martin notes that many of the employees in Scotland are immigrants who have struggled to find jobs in other areas because of systemic racism and xenophobia, especially during the pandemic.

These apps have been one of the few places hiring over the past year– picking up people who lost their jobs in hospitality. They can appear to be creating jobs because they don’t guarantee employees any base wage or hours. They can hire as many people as they want, and those people have to compete for the work available.

In fact, these companies take on very little responsibility at all. Couriers are set up to take the fall when restaurants put in the wrong order or take too long to prepare food. Their work is allocated, regulated, and taken away by an algorithm, rather than a human, meaning there is no transparency or accountability. Martin says couriers don’t know how their fees are calculated or how wait times are determined and often have their contracts terminated without explanation or right to appeal. As such, there is a tremendous amount of pressure on them to meet the demands set out. He cites an instance in which the app told him to cross town in one minute; an impossible task. All of these conditions affect safety and, of course, pay: “on average, in a day, I don’t think a Deliveroo rider can make more than like, four or five pounds an hour, which is obviously not enough to support a family or just to support yourself”. On top of this, couriers are responsible for the costs associated with the cars or bikes they use to do the work.

For Martin, the precarity he experiences at work stems from the ongoing evisceration of workers’ rights; the façade of an equal partnership between these companies and self-employed couriers is just well-marketed exploitation. In this context, an organised workforce is as necessary as ever.

Martin refers to the IWGB Couriers as a union, though the companies whose employees unionise under it refuse to recognise it as such. It is a UK-wide organisation that started organising in Scotland shortly before the pandemic took hold of the country. The lack of union recognition and precarity of their contracts means workers can be terminated for organising.

Despite this lack of recognition and the related denial of collective bargaining rights, the IWGB has achieved a lot. They’ve introduced weather-related fee boosts, and a “reject” button for orders riders don’t want to take: “Before, you had to accept the order, and you had to deliver it. Sometimes I don’t want to deliver something because it’s going from the city centre to the airport, and I don’t want to cycle for an hour and a half to deliver something”. The joy of solidarity is palpable when Martin talks about these wins, “collectively we fought for these rights […] it’s a very lonely job, you’re just on your bicycle, you just feel alone [but] you can take part in the union, you can organise, you can help organising. That’s important”. He is similarly effusive about casework, “when you have a case with a worker and you manage to at least make it a bit better for them… it’s just like, everything.”

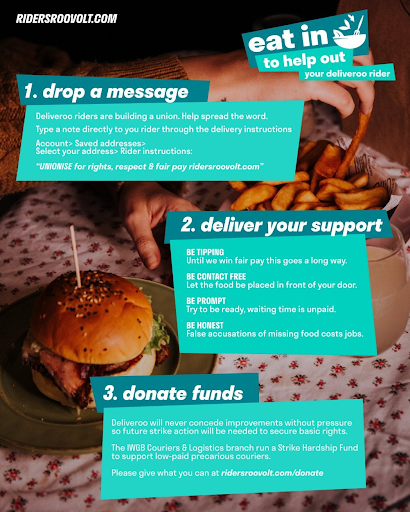

Organising in this context means getting creative. With no workplace, organisers rely on handing out leaflets with union information, which during the pandemic has adapted to putting stickers with QR codes on bags and next to restaurants. They ask supporters to add a rider’s note when they place deliveries directing riders to information about the union. They offer trainings on organising and casework, as well as other issues affecting workers, like tenants’ rights. They use a range of tactics, including strikes, boycotts, and campaigning, to make their demands. Some of these are longstanding demands, including a living wage, union recognition, and Limb B workers status, which “ is for workers who are self-employed, but work for a bigger company, […] that would give us access to seek holiday pay [and] things like minimum wage as well”.

Other demands have been shaped by the pandemic– like full pay for self-isolating riders, an end to unexplained, unappealable terminations, and access to toilets. The latter has been a significant problem, especially “for people who have their periods and they’re working […] this is quite terrible because then you just can’t work”. The union managed to secure these rights through a collective campaign spearheaded by the woman and non-binary officer.

They also have demands related to the recognition that they have been acting as key workers, with all of the risks that entails. In particular, they want PPE and vaccination. Martin says workers received PPE late and in woefully short supply– just five non-reusable masks. With regards to vaccines, “we’re not in the priority groups yet. But we are constantly seeing people […] Some people don’t wear masks, some customers open the door, they don’t wear a mask, and they don’t socially distance either.” Some restaurants have taken to providing hand sanitiser and wipes and being prompt with their orders, but the companies themselves have done nothing to ensure these protections are in place.

“I think the pandemic really highlighted how bad the conditions are for us”, Martin goes on. He is angry about the dissonance in what couriers are told by these companies and how they’re treated. The messaging is similar to that many key workers have received: “you’re heroes and your key workers. What you’re doing is so important, and we thank you. And, you know, when people clap at 6 pm is for you as well”. And yet, they aren’t offered any of the rights that should come from such a status.

It is perhaps because of this that, despite the increased difficulty in recruiting new members under social distancing, the union has grown significantly over the past year. They’ve taken advantage of online meetings and engaged with the movement internationally, building solidarity and learning from the ways other countries have won. Martin notes that “if Deliveroo has given a right to riders in the Netherlands, they’re going to have to give it to us as well”. Seeing workers in other countries win is galvanising; the campaign is looking at the upcoming Holyrood election and asking more of their representatives.

Looking to the future, Martin hopes the pandemic will serve to raise consciousness about the conditions couriers are facing and the need for a militant workers’ movements. “I hope, after the pandemic, or at least when it’s a bit better, people will realise that Deliveroo, Uber Eats, Just Eat and Amazon Flex, and, you know, all these companies have treated their workers really poorly”. Just today, the campaign is celebrating the UK Supreme Court mandating that Uber drivers should be classed as workers. He sees this as part of a broader movement that includes other frontline workers, like retail staff, but goes beyond that: “not just keyworkers, all workers. We have to make sure that after the pandemic, we don’t go back to being exploited”.

The campaign will be able to recruit people in the streets again, and Martin believes that this ability with the realisations that have developed over the last year will be a catalyst. The IWGB Couriers campaign will be able to show what they’ve won over the pandemic as evidence of what can be won, which Martin hopes will encourage others to join: “we can be really proud of the fact that we have had that power […] We can show them that collectively, we can achieve things.”

Get involvedYou can follow IWGB Couriers on Twitter. If you’re a courier, you can join the union at https://iwgb.org.uk/join/courier. If not, show your support by taking the actions on the leaflet attached.