Reflections on revisiting The Red Paper on Scotland

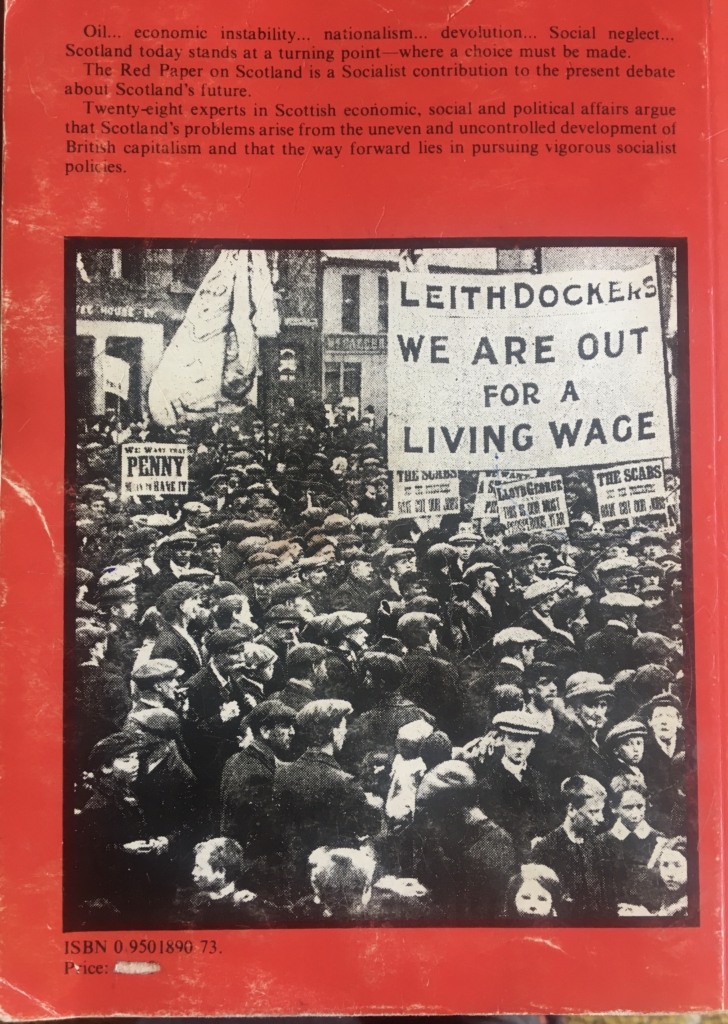

The Red Paper on Scotland, edited by Gordon Brown, Edinburgh University Student Publication Board 1975

This landmark collection of essays smells of 1975. When I take The Red Paper on Scotland down from the shelf I am transported back very precisely to my first year as a politics student at Edinburgh University. I know exactly what I was wearing and who I was with when we first flicked through the 368 pages of miniscule Times Roman.

We imbibed the heady aroma of full-blooded Scottish socialism, its base notes of Gramsci overlaid with the reek of avowedly progressive men sweating at the coalface of honest intellectual toil. This was surely my portal to the radical world I had imagined entering as an earnest young student activist.

Edited by Gordon Brown, former student rector and doctoral researcher who could be occasionally be seen stalking the campus in the vaguely Bryonic manner appropriate for one who was courting a Romanian princess, the book was a symposium on the possibilities – and resources – for a socialist future in Scotland.

What made this project stimulating and groundbreaking was the manner in which it straddled the hot topic of nationalism (and the seemingly immanent prospect of a devolved Scottish Assembly). As Brown boldly proclaimed in his introduction, ‘What this Red Paper seeks to do is to transcend that false and sterile antithesis which has been manufactured between the nationalism of the SNP and the anti-nationalism of the Unionist parties.’

Indeed. The illustrious gang of twenty-nine contributors included young left gunslingers shooting from the hip of various party affiliations, ideological and cultural positions. Academics, trade unionists, journalists, a couple of MPs and community workers, and a theatre-maker; all on the front line in a war of position which could transform Scotland (whether independent or as part of the United Kingdom was the moot point) into a radical democracy controlled by and for the working people of the nation. And every one of them a man (and all white men).

In truth, this review is not really a revisiting. Back in 1975 I didn’t get much further than reading Brown’s introduction and the substantial first article by that ‘intellectual godfather of Scottish nationalism’ Tom Nairn, who could be relied upon for a piquant turn of phrase to encapsulate the buoyant sweep of his thesis, that the recent advent of a North Sea oil industry and attendant surge in support for the SNP had generated political conflict which ‘has cut the palsied corpse of Unionism like a knife, exposing the senility of the old two-party consensus system’.

For my youthful self, the tiny type and competing attractions of university life were enough to consign The Red Paper to the ‘read later’ pile. That, and a whiff which was too redolent of the loudly self-confident young male Trotskyists of far left student societies.

The silences of Scotland’s left: then and now

Over the years, I have dipped back in occasionally, but to read the book systematically from this 21st century vantage point is to be transported back to another world. It is a world in which the monopolization of public space and discourse by white men is a given – barely worthy of remark, far less critique. There is certainly some trenchant analysis of the ills besetting Scotland, and yet the prevailing tone is surprisingly optimistic and confident about the prospects for a socialism shaped around notions of a traditional unionized industrial working class and a statist planned economy.

The writers acknowledge that the public realm is dominated by distinctively Scottish institutions of hegemonic civil society in lieu of constitutional self-determination. But while the class privilege and capitalist interests of that establishment are scrutinized, there is virtually no acknowledgement that it largely constituted a stultifying, reactionary patriarchy which could be actively hostile to women invading its jealously guarded power bases.

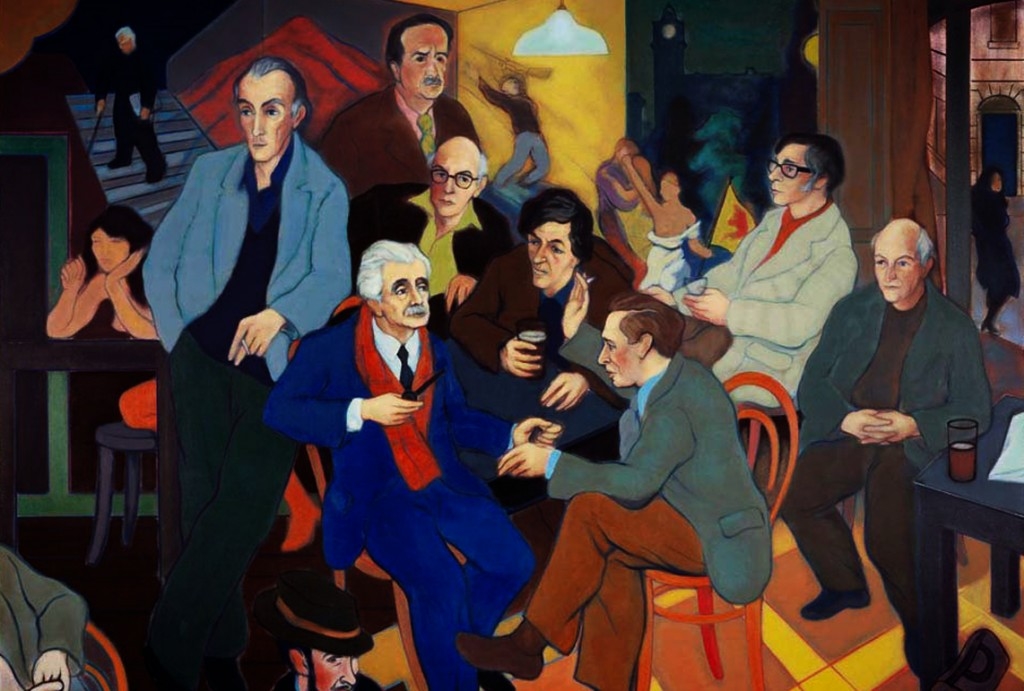

This is a pre-Thatcherite world of white men engaging in bracing dialogue about the future of the generic Scottish ‘He’ who symbolizes the potential agency of a revitalised, politically educated labour movement. Normalised masculine hegemony is the primordial Scottish soup. I can’t help thinking of Sandy Moffat’s much-loved painting, Poets’ Pub, which depicts a group of leading 20th century Scottish poets, all resolutely male, holding court in an Edinburgh pub. The only female figures are shadowy, peripheral, indistinct, faceless. You have to look pretty hard in The Red Paper for indications that women are part of this national story. They are voiceless, barely mentioned, on the margins…

As a feminist, active in struggles for gender and social justice in Scotland over the last forty years, I find much to appreciate and value in The Red Paper – as a historical document, but also for the ambitious sense of possibility and prescience which emerges from the jumble of tendentious and contradictory contributions. The presiding intellectual spirit is Gramsci, filtered through the lenses of Nairn and various exponents of the radical left, including Ray Burnett, Bob Tait and John McGrath, whose landmark play, The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil had brought the contested issues into sharp public focus in 1974. The framework for debate is constructed around the axes of class and national identity. That is productive of much useful but partial analysis, and occasionally prophetic prognosis.

The total absence of contributions by women, and more specifically of anything like a feminist perspective, is a lacuna which is hardly forgivable – even allowing for the times – and a real missed opportunity. By 1975 some of the foundational texts of the so-called second wave feminist Women’s Liberation had been around for a while. It was a movement which shared many common ideological and methodological roots with progressive socialists: in the international New Left struggles, intellectual currents and social movements of the 1960s. Indeed, Juliet Mitchell’s foundational article ‘Women: The Longest Revolution’ (1966) was published in that Gramscian house journal New Left Review.

Women’s Liberation, Men and the Politics of the Scottish Left

Scottish feminists rarely found a welcoming environment in left wing parties or the STUC. Their developing analysis of women’s exploitation and oppression as embedded and reproduced in patriarchal structures and norms and operational in the everyday practices of gender relations was too often ignored, or contemptuously dismissed as a bourgeois distraction from the class struggle. The routine sexism of too many male colleagues hardly encouraged a spirit of comradely collaboration.

Women’s Liberation groups in Scotland (from around 1970) were women-only spaces for consciousness raising and mobilizing for their own revolutionary project. As a contributor at a 2009 Scottish WLM oral history workshop recalled ‘Women were really remaking their lives…just blowing their lives to pieces. We really believed we were changing the world…we would overthrow years of patriarchy and start something new’.

In his introduction to The Red Paper Brown argues that ‘a socialist society must be created within the womb of existing society and prefigured in the movements for democracy at the grassroots’. Leaving aside his subsequent abandonment of that aspiration, I want to take young Broon at his word.

Look hard for any sign of women in this book, and you’ll find them lurking in the dark corners and peripheral schemes of 1970s Scotland. These are the places of everyday struggles for basic survival in the face of chronic poverty, unemployment, low pay, inadequate child care provision, damp and squalid housing, sexual violence, domestic abuse. Ian Levitt’s chapter concerns the ‘paradox of a new class of poor’ in affluent Scotland – the elderly (majority female), the long term unemployed, the ‘fatherless families’.

Brown outlines a rudimentary gender analysis of the benefits system and social security, constructed around the highly gendered presumption of male breadwinners earning a ‘family wage’. Social changes meant a huge increase in divorced, estranged and single women with children, dependent on social security, with no access to cheap or free childcare, and a job market offering little but low status work with appallingly bad pay. The gender pay gap figures quoted by Levitt lay bare the feminization of poverty and staggering economic inequalities between men and women. In 1973 over 90% of women in Scotland earned less than the average male wage, and 75% of women earned less than the bottom 10% of male earners.

Freirian community worker Colin Kirkwood throws some light on marginalized women from a different perspective, as activists in local Glasgow tenants associations and community groups. He observes that most core and active members are women, but that a few men tend to occupy and dominate committee positions. There are clearly gendered tensions at play, and intense conflicts between local activists and paid leaders. ‘The local women cannae get daein any bloody thing.’ Despite reactionary features of the groups he discusses, Kirkwood discerns potential as growth points for participative democracy.

This chapter reminded me of my own experiences as a youth worker living and working in Ruchill – the raw edges, the direct action of angry women at the conditions in which they were expected to live, and persistent failure of the local council to respond. In the thick of this very concrete micropolitics, they developed a critical consciousness of the burdens of oppression they had to carry, and resisted the hegemonic ‘common sense’ discourse that they were to blame for the dampness and mould, the chronic ill-health of their children. But there was always time for tea, bingo and the menage…

The first Scottish Women’s Liberation Conference was held in Glasgow in 1972. From around that time, the desire among some activists for practical engagement found a focus in activities to address domestic violence, or, as it was called then, the problem of ‘battered wives’ which was largely hidden from public view. The emerging Women’s Aid movement rudely pulled back the curtain to expose the shameful reality. It not only provided refuge and support for women and children, but challenged the dominant narrative by developing a gendered analysis of domestic violence as a pattern of coercive controlling behaviour which both reflected and served to consolidate men’s privilege and power: a socially structured reality in the ‘private’ realm of intimacy, marriage and family, and also in public institutions.

Cultural norms, but also the legal, material and economic conditions of women’s lives were intrinsic to the unequal gender order, which was both cause and consequence of sexual and domestic violence. The ‘family wage’ construct reinforced men’s household authority, obscured the importance of unwaged care and reproductive labour. This systemic androcentrism naturalised gender injustices and removed them from what was understood as politics.

The demands of the WLM, debated, formulated and agreed through the 1970s, were all about politicising the personal in an expanded understanding of social and economic justice. There were plenty of arguments between radical separatists (who rejected all existing political institutions as inherently hierarchical and oppressive) and socialists who sought to transform those institutions. Women’s trade union agitation for equal pay had already made an impact. Socialist feminists – the majority position in Scotland – were beginning to theorise and write about the particularities of their struggle in the Scottish context.

Gramsci and Scotland and the missing agenda in The Red Paper and since

If the relevance of Gramsci for a socialist Scotland lay, as Brown claimed, in recognising the significance of emerging grassroots struggles and their organic intellectuals, the book could have done with more contextual, granular analysis rooted in everyday lived experience of women, not to mention all those people belonging to minoritized identity categories who are completely ignored in the book. The collection evades any acknowledgement of Scotland’s homophobia, sectarianism, racism. It does not grapple with the complicated legacy of a nation implicated up to the hilt in Britain’s imperial enterprise. For a book about the operations of power, these silences are deeply problematic.

Brown’s failure to include feminist voices in this book was pretty shocking. From the edges of heteronormative paternalist conformity, Women’s Aid, Rape Crisis, the Scottish Abortion Campaign et al were emerging as (to use Nancy Fraser’s definition of the phrase) subaltern counterpublics, critically interrogating the interests and knowledge underpinning prevailing power relations in patriarchal Scotland, and attempting to model radical alternatives. It was from these standpoints that they considered questions of Scottish identity, devolution and independence.

By the mid-1970s the British Women’s Liberation movement was fragmenting, not least because those in Scotland were disillusioned with being dominated and marginalised by the London power base. Activists recall a palpable Caledonian cringe, and early attempts to analyse this phenomenon characterised Scottish culture and tradition as particularly reactionary, something usually attributed to the legacy of ‘the righteous wrath of Calvinist theology and social control falling heavily on the female sex’. But Catholicism was also in the mix – particularly in relation to reproductive rights. These religious institutions were considered to have a tenacious hold on Scottish political and public life, even if transmuted into partially secularised forms.

The fifth demand of the Women’s Liberation movement was women’s legal and financial independence, and in the later 1970s a working group produced a Scottish Women’s Charter, outlining proposals for a prospective Assembly relating to divorce, custody, housing, reproductive and maternity rights. Eveline Hunter, Elspeth King and Sheila Gilmore were among the socialist women who saw devolution as an opportunity to be seized. A few made the case for full independence.

But others were not at all confident that a Scottish Assembly, giving extended powers to a socially conservative masculinist political establishment, would mark an advance for women’s liberation. In the mid-1970s the majority did not see constitutional change or nationalism as the most effective way to change the position of women in Scottish society. They channelled their energies into social movements, local protest and action, single issue campaigns. That was more fruitful terrain in their struggles for redistribution, recognition and representation; for the critique and passion driving their ideological war of position in many small revolutions.

Strategically, this proved quite successful as a reform agenda through the 1980s and 1990s. For example, Women’s Aid and the wider movement against gender-based violence achieved significant changes in police practices, public attitudes, civil and criminal legislation. There was increasing feminist penetration of the Scottish state – in political parties, trade unions, local bureaucracy and especially municipal councils, through the women’s and equal opportunities committees. The extent to which this more pragmatic approach resulted in dilution and appropriation remains a contested issue, but the high profile Zero Tolerance campaign initiated by Edinburgh Council Women’s Committee in 1992 deliberately drew on Gramscian theory in its confrontational and highly effective promotion of a radical feminist definition of violence against women.

The emerging, broad based ‘women’s politics’ was shaped and galvanised by networks of women whose formative experience was in social movements, but who had also developed international links. Fluidity and capacity for goal-based coalition-building created conducive conditions which were catalysed during the new constitutional debate of the 1990s. This time around, the 50:50 campaign for equal representation in the new Parliament was framed as a signifier of the bright, progressive post-devolution future. It was described in 1994, by none other than Tom Nairn, as ‘an emblem of the kind of country and the kind of nationalism people really want’, portent of ‘a new start built around that act of liberation’ that would ‘lift our country and justify its return’. Alas, in the current febrile and fractious climate, that lofty sense of possibility seems as much from a different world as The Red Paper on Scotland.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. As I recall the hazy inadequacies of my own youthful political outlook, I am inclined to regard The Red Paper project in a generous spirit. But that being said, critical distance, (along with the intervening catastrophic impacts of globalised neoliberalism, obscene injustice and climate crisis) requires a more stringent assessment. My reflections here emerge from a particular life history of involvement in a social movement ignored by the book – one which has driven significant social and cultural change in Scotland.

The absence of feminist voices is emblematic of this book’s narrow channels and underlying nostalgia. For all its vaunted openness to creating a forum for articulating alternative visions of a socialist nation, the overall impression remains of a pretty homogenous group of men, at ease in their unexamined masculinist privilege, operating with taken-for-granted statist assumptions about the enduring nature of class, labour, work and the dynamics of power in a fast disappearing industrial economy, at the fag-end of Empire. The silences resound. The inattention to the low rumbles of a different drumbeat. Far from being a calling card for the vanguard of a future radical Scotland, was The Red Paper on Scotland not perhaps a testament to the vestiges of a profoundly conservative worldview?

This is an excellent piece.

Addressing issues like patriarchy and secrarianism would have required a critical examination of Scottish Presbyterianism, which might not have been congenial to Gordon Brown.

Patriarchy and sectarianism were the great banes of traditional working-class politics back in its glory days. Women were often confined to making the tea while the men schismed.

Yes, hindsight is a wonderful thing. Who would have imagined, back in the mid-’70s, that so profound a revolution was about to occur in our relations of production that would pull the rug out from under the feet of the established Left.

(BTW In the 1980s, contrasting them with the Militant Tendency , we used to refer to the other wing of bourgeois entryists to the Labour Party, to which Brown, Darling, Griffiths, etc. belonged, as the ‘Stripey Jumper and Kickers Brigade’ or ‘Magic Roundabout Tendency’. Again, little did we think that, in another ten years, Florence’s friends would have become New Labour?)

I enjoyed the article and the critique.

However, as a member of the 1960s generation at university, and the young women I met in these days, including the one who has co-owned our worldly goods for 50 years, I think that by focussing on the Women’s Movement (capital letters) you ignore the conduct and attitude of many of the women who did not participate in the Movement (capital letter, again). All of these women are now in their 70s and many have grandchildren and many live quite affluent lives nowadays. Most of them certainly do not feel beholden to men and have let their daughters and sons know that. These were the first group of women who used the Family Planning Clinics, which were being set up in Glasgow and Edinburgh and they braved the bullying and abusive actions of the religious zealots who picketed the clinics. Many of them cohabited with partners; some eventually married, but others did not. Many faced pressures from families for whom the attitudes of the Presbyterian church and the Roman Catholic Church were more influential than today. Many had the support of their own mothers, who had lived through the War, fulfilled important and responsible jobs only to be dismissed when the men returned from the War.

Of course there is much to be done to give women genuine equality, but many women who were not parts of the Movement (capital letter gain) lived lives in which every day they attempted to demonstrate, by just doing, that they were autonomous persons who actually had equal rights, even though the ‘had’ was sometimes aspirational.

This is a brilliant analysis which chimes with my own memories and experience. As a historian I am minded to reflect, that in terms of Scotland’s political progress, it is three women who stand out. Winnifred Ewing, Margo Macdonald, and Nicola Sturgeon. They have pierced that masculinist, class-based view of Scottish politics as a male domain.

An excellent piece, and a great read. But the patriarchy is alive and still kicking in Scotland, including within sections of the Yes movement.

How right you are