A Defence of Adam Smith, from Chomsky and Kropotkin

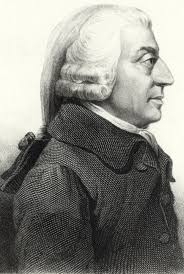

How should the influential and controversial figure of Adam Smith be seen? Smith is, arguably, the most famous of Scottish thinkers. He is frequently dismissed by the left as an apologist of the free market and all its woes. But this is a serious misunderstanding argues Richard Gunn.

How should the influential and controversial figure of Adam Smith be seen? Smith is, arguably, the most famous of Scottish thinkers. He is frequently dismissed by the left as an apologist of the free market and all its woes. But this is a serious misunderstanding argues Richard Gunn.

In his Understanding Power, published in 2003, Noam Chomsky comments on Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations.1 In his On Anarchism of 2013, an equivalent passage appears.2 I quote part of the On Anarchism version:

“Well, that’s real scholarship: suppress the facts totally, present them as the opposite of what they are, and figure, “probably nobody’s going to read

anyhow, because I didn’t.” I mean, ask the guys who edited it if they ever read to page 473 – answer: well, they probably read the first paragraph, then sort of remembered what they’d been taught in some college course.” 3

Here, I do not take issue with specific editions of the Wealth of Nations. And I put it on record that Adam Smith scholars whom I have encountered have unfailingly been scrupulous where textual matters are concerned. However, I report that undergraduate students – I have in mind Bush-era students from the U.S.A. – proceed (or have proceeded) as though “real scholarship” as sarcastically described by Chomsky is their aim.

In part, the fault in such hasty readings lies with Smith himself. The first three chapters of the Wealth of Nations emphasise that the division of labour is vital to the increase in productivity that ‘commercial society’ 4 has seen. It is several hundred pages later that Smith delivers the damning verdict that he passes when the division of labour is seen not in narrowly economic but broadly social terms:

“He [the worker in commercial society where a social division of labour prevails] naturally loses…the habit of…exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him, not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any judgement concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life. Of the great and extensive interests of his country, he is altogether incapable of judging…” 5

The scenario which Smith has in mind, and fears, is one where a worker whose labour is subdivided finds that the blinkers which are inseparable to such a division are moulded to his or her eyes or head. Such a worker cannot change the angle of his or her vision; he or she cannot shift from issues that are particular to the task performed to questions of a universal or, at least, more far reaching kind. Conversation involves a shift to universal or, at least, more far reaching perspectives and this becomes problematic where a detail worker is concerned. In the opening chapter of the Wealth of Nations, Smith persuades himself that ‘a great part of the machines made use of in those manufactures in which labour is most subdivided , were originally the inventions of common workmen,’6 but the passage just cited on increasing stupeifaction casts doubt on whether growing enlightenment is the division of labour’s most likely result. Later in Smith’s argument, a reader learns that education which is needed to keep commercial society on course. The enthusiasm for the division of labour which prevails in the opening chapters and the darker tones of his later discussion pull in opposed directions. The point may be stated using Chomsky’s terms.

If a reader bases his understanding of the Wealth of Nations solely on chapters I-III, a reader – whether a Smith scholar or a student of the Bush era – forms a misleading (and misleadingly roseate) impression of Smith’s views. If a reader bases his or her understanding on the Wealth of Nation’s opening chapters, a distorted impression of Smith (a distortedly roseate impression) results. If the first chapter lauds the inventiveness of the ‘common workmen’ whose labour is subdivided, Smith later on concedes that education partially ‘paid by the publick’ is needful to keep commercial society on its rails. The positive view of the division of labour which prevails in the Wealth of Nations’ opening chapters and the passage (already quoted) on stupidity and ignorance pull in directions that are opposed.

This point can, I suggest, be generalised. In my comments, I have focused on the issue of the division of labour. For a reader of the Wealth of Nations, this issue is all important. We should be clear, however, that the division of labour is only one topic amongst others where, on a reading of Smith as a proto-neoliberal author, discordancies exist. To take just one example: ‘merchants and manufacturers’ are presented in the Wealth of Nations in far from flattering terms. Writing on Smith, John Dwyer goes so far as to say that merchants and manufacturers ‘were…the target of most of Smith’s criticisms in his great economic work’.7 Their difficulty is that merchants and manufacturers press for a social monopoly8 and a high rate of profit (which they see as being in their interest) does not coincide with the good of society as a whole.9 Here, I mention Smith’s portrayal of merchants and manufacturers only in passing. It jars with the right wing interpretation of Smith as a free market liberal for whom entrepreneurship has a heroic ring.10

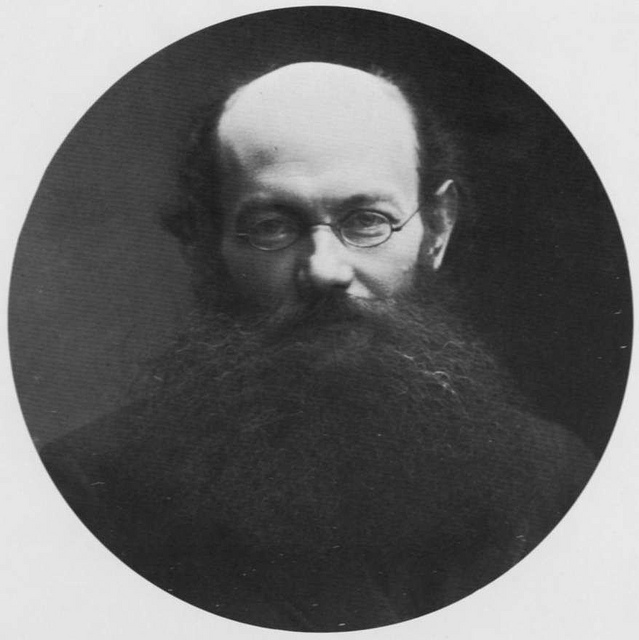

My defence of Noam Chomsky’s observations on Smith in 2003 and 2013 have bearing on how Smith’s writings should be read. Too frequently in, at any rate, Anglophone discussion, left wing radicals take it for granted that Smith upheld what would, later, be neoliberal views.11 Perhaps it comes as a surprise to the present reader that Chomsky, who writes as an anarchist, should provide pointers towards Smith’s arguments. Whether this counts as surpising, I propose that Chomsky is valuable in just this way. In the remainder of my paper, I find a similar value in comments which Prince Pyotr Kropotkin’s writings contain.

In his Modern Science and Anarchism, a short work published in 1923, Kropotkin refers to what he terms Adam Smith’s ‘best work’. This work, which Kropotkin refers to as The Origin of Moral Feeling,

found that the moral sentiment of man derives its origin from a feeling of pity and sympathy which we feel toward those who suffer: that it springs from our capacity of identifying ourselves with others; so much so that we almost feel physical pain when we see a child beaten in our presence, and our nature revolts at such behaviour.12

I quote Kropotkin not because I regard him as an infallible historian of ideas. To touch on the obvious point first, Kropotkin in the passage quoted gets the title of Smith’s ‘best work’ wrong. By The Origin of Moral Feeling, he means The Theory of Moral Sentiments, the first edition of which was published in 1759. The relation between the Theory of Moral Sentiments and the Wealth of Nations has come to be referred to as the ‘Adam Smith problem’ – to borrow Goçmen’s title.13 The ‘problem’ is that of how Smith’s chief works are related and, before leaving the title which Kropotkin foists on Smith, we may note that there is something felicitous in Kropotkin’s mistake. Although Smith did not write a book entitled The Origin of Moral Feeling, the Theory of Moral Sentiments addressed the question of the foundation or ‘origin’ on which ethical judgements rest. Smith’s contemporaries – for example, Henry Home (Lord Kames),14 Thomas Reid15 and Adam Ferguson16 – were quick to appreciate that Smith’s remarks on sympathy and pity in the Theory of Moral Sentiments address the question of the basis on which ethical evaluation rests. Although present-date commentators are less explicit in pointing to foundations as the Theory’s central topic, Kropotkin’s use of the term ‘origin’ keeps alive a tradition of reading that obtained in Smith’s day. If, indeed, Smith employed the title that Kropotkin foists upon him, it may be that present-day debates on Smith would have had a sharper focus than is currently the case.

I quote Kropotkin not because I regard him as an infallible historian of ideas. To touch on the obvious point first, Kropotkin in the passage quoted gets the title of Smith’s ‘best work’ wrong. By The Origin of Moral Feeling, he means The Theory of Moral Sentiments, the first edition of which was published in 1759. The relation between the Theory of Moral Sentiments and the Wealth of Nations has come to be referred to as the ‘Adam Smith problem’ – to borrow Goçmen’s title.13 The ‘problem’ is that of how Smith’s chief works are related and, before leaving the title which Kropotkin foists on Smith, we may note that there is something felicitous in Kropotkin’s mistake. Although Smith did not write a book entitled The Origin of Moral Feeling, the Theory of Moral Sentiments addressed the question of the foundation or ‘origin’ on which ethical judgements rest. Smith’s contemporaries – for example, Henry Home (Lord Kames),14 Thomas Reid15 and Adam Ferguson16 – were quick to appreciate that Smith’s remarks on sympathy and pity in the Theory of Moral Sentiments address the question of the basis on which ethical evaluation rests. Although present-date commentators are less explicit in pointing to foundations as the Theory’s central topic, Kropotkin’s use of the term ‘origin’ keeps alive a tradition of reading that obtained in Smith’s day. If, indeed, Smith employed the title that Kropotkin foists upon him, it may be that present-day debates on Smith would have had a sharper focus than is currently the case.

Besides the issue of ‘foundations’ and ‘origin’ what else may be learned from Kropotkin’s brief passage on Smith? The circumstance that most dramatically confronts a reader of Modern Science and Anarchism is the remark that the Theory of Moral Sentiments – or, as Kropotkin calls it, the Origin of Moral Feeling – is Smith’s ‘best work’. Elsewhere, I have argued that Smith’s comments on pity and sympathy are, in effect, a discussion of human interaction:17 when Smith discusses sympathy or empathy, and when he argues that individuals see themselves ‘with the yes of other people, or as other people are likely to view them’, he is, in effect, anatomising a form of to-and-fro intersubjectivity that lies at the core of human society per se. Read in this way, the Theory of Moral Sentiments may or may not be Smith’s ‘best’ work. It is, however, immensely ambitious and it is central to Smith’s work.

In a moment, I shall relate the Theory of Moral Sentiments (thus interpreted) to the Wealth of Nations. I shall outline way in which the ‘Adam Smith problem’ may be solved. Before attempting this, I take a step closer to the detail of the Theory of Moral Sentiments’ discussion.

Let me proceed by quoting a further anarchist theorist. In her autobiographical Living My Life, Emma Goldman refers to Kropotkin as ‘the most outstanding exponent of anarchist communism’.18 Here, I do not attempt to fill out the term ‘communism’ but ask a seemingly tangential question. Do the categories of Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments help us to clarify the sort of society that Kropotkin, as an anarchist, has in mind?

The answer to this question is, surprisingly, ‘Yes’. The Theory of Moral Sentiments pictures an interrelation between a Self and an Other – in effect, a conversation – where each subject places him or herself in the position which the other holds. Neither subject can know the other’s sensations directly but each may, through imagination, ‘place ourselves in the situation of another man, and view it, as it were, with his eyes and from his station’.19 Smith pictures a conversation between such subjects as one which involves two distinct conversational or interactive roles. One role is that of ‘the spectator, whose sentiments…I endeavour to enter into’ and the other is ‘the agent, the person whom I properly call myself’.20 If the conversation or interaction is one where ‘all participants’ have an equal chance to perform different ‘speech acts’,21 then the situation is characterized by a maximal amount of liberty and where something approaching what Goldman terms ‘anarchist communism’ may appear. I do not, here, enter into the interpretative work which an account of Smith along these lines require. But I sketch ideas that indicate what may be a conceptual bridge between Smith’s ‘best work’ and anarchistic thought.

I return to the promised discussion of the ‘Adam Smith problem’. What relation might there be between the Theory of Moral Sentiments and issues that the Wealth of Nations explores? Connections appear, I suggest, if the stupidity and ignorance entailed by the division of labour22 are thought of as problems of compartmentialisation. It may be that Smith considers that in a commercial society, where a social division of labour is omnipresent, labourers are tied, day in and day out, to the tasks that they perform. It is because they are tied and restricted in this fashion that they cannot engage in ‘rational conversation’ where universal (or more universal) issues are at stake. If the Theory of Moral Sentiments attempts to identify a to-and-fro dynamic of conversational interaction that is essential to all society, ‘commercial’ society eats at the foundations of social life per se. If this is, indeed, the line of argument that Smith is pursuing in the Theory of Moral Sentiments and the Wealth of Nations, it is absurd to see his work as a hymn of praise to market relations. The Wealth of Nations carries on from Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality of 1755, which Smith admired,23 and projects a critique of political economy (to employ Karl Marx’s phrase).

*

1) N. Chomsky Understanding Power (London: Vintage Books2003) pp. 390-1.

2) N. Chomsky On Anarchism (London: Penguin Books 2013) pp. 36-7.

3) On Anarchism p. 37.

4) A. Smith An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations [henceforth WN] p. 37.

5) WN p. 782.

6) WN p. 20.

7) J. Dwer The Age of Passions (East Linton: Tuckwell Press 1998) p. 43.

8) WN p. 84

9) WN p. 266

10) For a reading of Smith much closer to my own – and to Chomsky’s – than to neoliberalism’s, see N. Davidson, P. McCafferty and D. Miller Neoliberal Scotland (Newcastle uon Tyne: Cambridge Schoilars Publishing 2010) pp. 3-6.

11) A welcome exception to this generalisation is D. Goçmen’s The Adam Smith (London: I.B. Tauris 2007). Goçmen’s valuable study is cited in Davidson et al. Neoliberal Scotland at p. 5.

12) P. Kropotkin Modern Science and Anarchism, Second Edition, (London: Freedom Press 1923) p. 8.

13) Referred to in Davidson et al. Neoliberal Scotland p. 5, footnote 21.

14) H. Home [Lord Kames] Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion (Indianapolis: Liberty Press 2005) p. 71.

15) See E.H. Duncan and R.M. Baird ‘Thomas Reid’s Criticisms of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments’ Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 28, No. 4 (1977).

16) A Ferguson ‘Of the Principle of Moral Estimation: David Hume, Robert Clerk, Adam Smith’ in his Selected Philosophical Writings (Aberdeen: Imprint Academic 2007) pp. 164-5.

17) See R. Gunn ‘From Smithian Sympathy to Hegelian Recognition’ in H. Hapuku, M. Aydin, Ismail ŞirinerF. Morady and Ū. Ҫetin, eds. Politik ﺃ Iktisat ve Adam Smith (Istanbul: Yon Yayinlari 2010) pp. 2-4. The paper, which was given at the International Conference on Political Economy: Smith at the University of Kocaeli in October 2009, is available at my website: http://www.richard-gunn.com.

18) E. Goldman Living My Life (London: Penguin Books 2006) p. 111.

19) TMS pp. 109-110.

20) TMS p. 113.

21) I quote from T. McCarthy The Critical Theory of Jūrgen Habermas (Cambridge: Polity Press 1984) p. 306.

22) See the passage from WN quoted at note 5, above.

23) See A. Smith ‘Letter to the Edinburgh Review’ in Smith’s Essays on Philosophocal Subjects’ (Indianapolis: Liberty Classics) 1980 pp. 250-6.

To be fair, Kropotkin read (and wrote in) many languages; how do we know in what language he read Adam Smith? Modern Science and Anarchism was published in 1903, not 1923, in Russian; it was translated into English in the same year, by an American, David A. Modell. Although he was living in England at the time and certainly could write very good English, he did not write Modern Science and Anarchism in English.

So to say ‘Kropotkin got the title wrong’ is doubly unfair. What Kropotkin wrote was a rendition of the title into Russian; he is not responsible for its subsequent translation back into English. And, as I said above, we don’t know whether Kropotkin read Adam Smith in English, or in French, Italian, German or Russian translation.

The intellectual movement of Anarchism originated in the writings of the Scots and the French philosophers of the middle and end of the eighteenth century.

http://jackelliot.over-blog.com/

https://i1.wp.com/bellacaledonia.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Painting_of_David_Hume.jpg?resize=461%2C567

Further to “Modern Science and Anarchism,” yes it was originally published in Russian in 1903. The 1923 edition was a reprint of the expanded 1912 edition — which, in turn, was a shorter version of the much longer 1913 French work which included, as well as a longer version of “Modern Science and Anarchism”, three other works (“Communism and Anarchy”, “The State: Its Historic Role” and “The Modern State” plus as appendix on Herbert Spencer and a glossary).

Given the scope of the work, it seems incredibly petty to mention the mistake — surely a product of the many translations involved (English to Russian to French and back to English).

I should also note that Kropotkin wrote sympathetically on Smith in other chapters of this book — and elsewhere. He was keen to note the differences between Smith and those who invoke his name to justify capitalism — Smith was never that. As Proudhon — and, later, Marx — noted, Smith looked at the system “warts and all” and did not (usually) indulge in the apologetics of later economists. Kropotkin echoes this (see “Anarchist-Communism: Its Basis and Principle”, for example).

Finally, I must note I have just finished the work on getting the 1913 French edition of “Modern Science and Anarchy” into English — it will be published by AK Press next year (2018):

http://www.anarchism.pageabode.com/anarcho/libertarian-proudhon-modern-science-anarchy-update

So Kropotkin’s final book published in his life-time is finally available, in full, in English. It makes interesting reading.

Given the scope of the work, it seems incredibly petty to mention the mistake — surely a product of the many translations involved (English to Russian to French and back to English).

I should also note that Kropotkin wrote sympathetically on Smith in other chapters of this book — and elsewhere. He was keen to note the differences between Smith and those who invoke his name to justify capitalism — Smith was never that. As Proudhon — and, later, Marx — noted, Smith looked at the system “warts and all” and did not (usually) indulge in the apologetics of later economists. Kropotkin echoes this (see “Anarchist-Communism: Its Basis and Principle”, for example).

Further to “Modern Science and Anarchism,” yes it was originally published in Russian in 1903. The 1923 edition was a reprint of the expanded 1912 edition — which, in turn, was a shorter version of the much longer 1913 French work which included, as well as a longer version of “Modern Science and Anarchism”, three other works (“Communism and Anarchy”, “The State: Its Historic Role” and “The Modern State” plus as appendix on Herbert Spencer and a glossary).

Finally, I must note I have just finished the work on getting the 1913 French edition of “Modern Science and Anarchy” into English — it will be published by AK Press next year (2018)

So Kropotkin’s final book published in his life-time is finally available, in full, in English. It makes interesting reading.

My feeling about the Wealth of Nation is that Smith did more harm than good through no fault of his own.

The work is a devastating critique of the establishment of the day that codifies for the first time the true sources if their power, namely primogenature and ‘entails’, and the ways they use that power to maintain their position.

He assumes, wrongly, that once the facts enter the public domain common sense will prevail and the establishment will realize that their behaviour is restricting economic growth and begin to institute reforms.

What it appears actually happened was that the only people with the time and intellectual capacity to understand what Smith was talking about were the very people he was attacking.

His theories never gained any serious traction during his lifetime but the establishment was able to benefit from a clear explanation of the real sources of their own power and began to use that information to strengthen and further improve their position. Once Smith was safely dead and unable to defend his arguments they began to twist his own words to support liberalisation of markets that allowed even more monopolistic and exploitative behaviour.

I don’t think that is true. I have not got a reference immediately at hand but I believe one of his arguments is that the working people are so busy just surviving that they often don’t have time to understand or pursue their own interests. There’s also extensive argument in the early books of Wealth on the disadvantages the workers have in pursuing their interests, when they do understand them, against their employers.

I am not sure that’s quite right either. He makes a distinction between the merchant classes and the landed gentry/political classes. You can get a taste of how he thinks the relationships work between the three classes in IV.2.43.

His argument was clearly geared at the political classes. But he wasn’t very success in reaching them in Britain. Around the time he died the French Revolution got underway and many of his friends started the task of spinning his writings to make them seem less radical. You can see that passages like this one from Moral Sentiments in the context of the French Revolution might be seen as somewhat threatening:

He’d also already had a much better reception in revolutionary America (not surprising given what he has to say about the American colonies in Wealth). But there influence is also because Scottish educationalists, people educated in Scottish universities, were the dominant force in American education during the late colonial and early revolutionary period. Madison, for example, was educated at a Presbyterian college, that at the time was the leading college of higher education in America. You can see the influence of Smith and Hume in Madison’s writings on factionalism in the Federalist Papers.

The passage quoted above is from in Moral Sentiments VI.2.37. The two principles of which he speaks are given in the previous paragraph (36):

Now read the last part of 37 which seems wholly applicable to the current situation people find themselves in in the UK and its various parts:

Given Andrea Leadsom’s comments about the need for “patriotic coverage” and the endless Tory calls for national unity and getting behind the government, one may well ask, given the two principles and their “drawing in different ways”, what is patriotic?

A few years ago, Ian Dale, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iain_Dale published on his website the transcript (including outtakes) of an interview with Alex Salmond

Alex Salmond’s view of AS’s work was closer to historical readings than to that of the AS society.

Henry Thomas Buckle’s 1872 Introduction to the History of Civilisation in England was designed to provide context to a much larger study never completed. At p 432- begins an evaluation of AS’s two books, as two parts of a unified concept, each of them essential to understanding of the other.

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8X8lyS2RQUoC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

I am grateful to Simon Brooke for his information on editions of Modern Science and Anarchism. I think that, as a reader of my piece will be clear, my aim is not to score points against Kropotkin. On the contrary, I use comments by Chomsky and Kropotkin as springboards to reach a non-establishment reading of Smith’s work.

I’ve always found it somewhat ironic that commentators point to division of labour as central to the tenets Smith espoused. Enlightenment Edinburgh saw exponential growth in social science precisely because those of philosophical bent pursued thought from tangential points of view. Smith was himself a Moral Philosopher, Hutton a chemist, Hume a historian.

I found Smith’s Theory of Modern Sentiments a staggeringly turgid read, and even an abridged version of Wealth of Nations really hard work too. I read WoN partly at breaks at work and read some of his capitalist-bashing comments out loud to my workmates.

I wish the Scottish Enlightenment had concentrated on inventing something like a word-processor, and perhaps some chart/diagram-design/printing technologies which WoN especially cries out for.

However, I would recommend Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, especially for any David Attenborough fans, where the writer picks up on one of the challenges Darwin left.

Correction: Theory of *Moral* Sentiments, of course. I could do with an edit function myself, obviously.

After calling Smith’s prose turgid, it occurred to me that writers during the Scottish Enlightenment may have been deliberately obscure, ambiguous or verbose to disguise radical opinion that would have got themselves into trouble such as their more radical counterparts in France.

Can anyone throw light on whether an element of fear (for reputation, position, liberty or life) helped foster a somewhat difficult writing style that would exhaust censors and deflect clerics?

As MBC points out, he was attacking mercantilism; not capitalism. The term capitalism tends to get used rather loosely. Smith talks about capital but the term capitalism does not appear to come into use until the maybe the 1830s or even later. The term capitalism when used broadly tends to hide the fact that market systems take different forms in different places and times. And the ideologies that rationalise the inequality that exist with different forms tends to take different forms as well.

Pay attention to Smith on factionalism. That’s a constant…It’s always there no matter what the political system. Any type of political reform, see above, has to come up with some sort of practical solution to contain and limit factionalism.

Google seems to think that venality is a synonym for mercantilism, in which case some of those quotes were likely about mercantilism, marketing-rigging and profiteering. My workmates would probably have shrugged if I had said mercantilist-bashing, but I take your point, @Alan.

Venality is probably an understatement, especially with regards to the British East India Company. See William Dalrymple’s essay (book forthcoming).

For an essay on Smith’s critique of the EIC and joint-stock corporations, see Sankar Muthu’s Adam Smith’s Critique of International Trading Companies Theorizing ‘Globalization’ in the Age of Enlightenment. Political Theory 36, no. 2 (April 1, 2008): 185–212.

Adam Smith was attacking many things — including state intervention for the few. After all, parliament was elected by the wealthiest 5% of the male population. So at the time, arguing against State intervention meant arguing against the few using the State to bolster its position. He made the point many a time. For example:

“Whenever the legislature attempts to regulate the differences between masters and their workmen, its counsellors are always the masters […] When masters combine together in order to reduce the wages of their workmen, they commonly enter into a private bond or agreement, not to give more than a certain wage under a certain penalty. Were the workmen to enter into a contrary combination of the same kind, not to accept of a certain wage under a certain penalty, the law would punish them very severely; and if it dealt impartially, it would treat the masters in the same manner.”

And:

“Merchants and master manufacturers [… have] a very simple but honest conviction that their interest […] was the interest of the public. The interest of the dealers […] is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public. [… and] have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.”

I have written on this aspect of Smith here:

http://anarchism.pageabode.com/anarcho/poor-adam-smith

Smith was also well-aware – unlike, say, the “Adam Smith Institute” – that working for a boss is not the same as working for yourself. His ideal seems to be self-employment.

So much of “The Wealth of Nations” is a critique of mercentilism but a lot of it is also a critique of capitalism – or an honest account of how capitalism works. As I said originally, the apologetics associated with modern-day economists is generally lacking in his work.

And, finally, I should also note that Smith is quoted favourably by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as well. For example, in the conclusion of “System of Economic Contradictions”:

“The justice that Adam Smith would like to establish is impracticable in the regime of property.”

Proudhon recognised that Smith had argued that the worker’s wage was their product and that capitalism denied this — he “shared” his rightful income with the landlord and employer. Proudhon, like other anarchists, wanted to socialise property to ensure workers were no longer exploited. Obviously Proudhon and Kropotkin disagreed on how best to do this but both argued for workers’ co-operatives, workers’ self-management, socialisation of the means of production.

I’m struggling with WON right now. I paused to see whether there was something online that could help me with this. I have zero specialized education or knowledge. But I do a lot of reading, even when it’s over my head. The ‘over my head’ reading that I do is usually by accident. Sometimes it rewards. Sometimes it doesn’t. I’m going to offer here a quick mention of something about Darwin that not enough folks know about (and many, among the elite, don’t want to know about): Functional Darwinian evolution is dead. I have read both of Michael Denton’s books on the crisis of Darwinian theory. Both were over my head. The second one was harder for me to digest than the first. But I found much in them to take away. And, at the conclusion of Michael’s updated book about the crisis of Darwinian evolutionary theory, I was clear about the gist of Michael’s argument. Structuralism (in which adaptive features were always there, immanent, in whatever life forms you are looking at) is in. As a Christian (and certainly not a rightwinger who might like Darwin’s ideas for obvious reasons; namely as a body of thought that can be twisted to serve dark ends), I appreciate Michael’s efforts to do science and not fantasy or politics masquerading as science. I don’t believe that the Truth clashes with science. Look into it if you’re not afraid.

Note that smith railed against the concept of corporate ” limited liability ” on the ground that it would encourage management to take reckless gambles with other people’s, shareholders, money with no consequences for them. The consequences of the recklessness he warned against are all around us. With more every day.

I treasure his words on ” conspiracies against the people ”

To present him as an apostle of corporate capitalism is very far from the truth.

I’m nowhere near as informed as these other commenters, but I’m trying.

Smith was trying to argue for a moral economy. He was firstly a Moral Philosopher. He railed against the East India Company and its monopoly and argued for free trade against mercantilism which was the dominant philosophy at the time. He argued that monopolists misunderstood trade and wealth as a fixed cake that you had to get the largest share of, or your enemies would, arguing instead that trade and commerce was a live thing that could be positively enlarged if it was allowed to flourish freely.

He wrote ‘the business of the merchant is always to defraud the public’. Whilst he argued for free trade he did not support deregulation.

Smith is not a particularly “controversial figure” among Smith scholars. What’s scandalous is that neoclassical economists and neoliberals have promulgated a version of Smith that’s at odds with what Smith wrote and intellectual scholarship. The Left misunderstand Smith because they take the Right’s appropriation of Smith at face value and as an honest appropriation when it’s mythology and rationalisation.

For anyone interested in Smith scholarship, I’ve found books by Samuel Fleischacker and Jerry Evensky useful.

Gavin Kennedy, who was a player in the SNP in times past, also has a book on Smith and one forthcoming later this year. There’s often interesting stuff on his Smith blog. A post on his blog earlier today links to an obit for Donald Winch, another scholar worth reading on Smith.

Smith, it seems to me, has been wilfully misunderstood/mininterpreted by some more modern commentators to give credence to their fundamentalist free-market dogma. One wonders how many have actually read him. The “invisible hand” is the classic example. Here Smith seemed to making a simple point, that in setting up an enterprise an individual creates benefit for himself and incidentally also for society as a whole, presumably by creating employment and profits, some of which are recycled into the community. How that gets translated into the neoliberal nirvana of small government and unrestrained free-marketeering I do not know.

Is it not the case that Kropotkin read Adam Smith in French translation? While he was a prodigious linguist, English was his seventh or eighth language. If so, the title he quotes for Adam Smith’s work is probably a translation into English of the title of the French edition.