Bombing Kelpies

A review of the journal, Dark Mountain,

A review of the journal, Dark Mountain,

Vol. 1, Summer 2010

The editors of Bella have kindly drawn my attention to this debate about the Dark Mountain Project that’s been playing out on Bella Caledonia and asked me if I’d like to contribute. As it happens, I have just finished reading, from cover to cover, Volume 1 of the Dark Mountain Journal. You can buy it on Amazon, though the Mountain guides might appreciate it being bought from their website – click here. I was one of the speakers at the festival, and it so happens that I have just finished reading, compulsively, from cover to cover, Vol. 1 of the Journal – a full-length hardback book. I’d been thinking that I’d write a review of the Journal for Amazon, but in the light of their prompt, I’ll post it first here on Bella Caledonia.

At the Festival my own keynote address followed on straight after that of George Monbiot’s. George’s was a debate with Dougald Hine. As has been widely reported elsewhere, he poured cold water on the idea that we could “uncivilise”. Dougald struggled to mount his defence and on the surface of it, George won. What’s more, I think it was imperative for the balance of the whole thing that such a level-headed perspective was heard. But in addition, something deeper was going on. By having George say what needed to be said the ground was cleared, in a funny sort of way, for another stratum of perspective to emerge, and I think most of the audience recognised that. At a rational level George was spot on and I started my presentation by saying that I pretty much fully agreed with his criticisms. When we’re now nearly 7 billion people in this world, bound in to an oil-driven economic system whether we like it or not, you have to be pretty careful about advocating heading off over the mountains to Shangri-la-de-dah. But there’s also a danger in being so practical that you miss deeper layers in life.

As such, I acknowledged the importance of the practical critique in my opening remarks, but suggested there’s also another stratum. Uncivilisation is simply not a manifesto that should be read in a practical, literal manner. Rather, it is a prophetic document in the sense of being “apocalyptic” – and that in the full theological sense that means “to remove the cover”, to reveal, thus why the Biblical book of Revelation is also termed “The Apocalypse”. To my eye what Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine have achieved – albeit in a manner that must inevitably be imperfect because it cannot yet (if ever) be fully achieved – is that they have lifted a veil on consciousness. They have revealed something of the interiority of the exterior state of the human condition. In the aftermath of Cop15’s failure on climate change and as the simulacrum war (for its perpetrators) of Afghanistan wears on, the stimulus of Dark Mountain transports many of us into a deeper paradigm of seeing and being. It reminds us that there is still an underpinning of magic that can quicken the heart, and insist on the essential over the virtual.

True, as somebody on the Bella Caledonia website says, Dark Mountain’s ideas are not new. There’s little that Dougald and Paul are saying that Ginsberg didn’t also say poetically in Howl back in 1955; or Whitman in 1855 with Leaves of Grass. Yet the time is ripe to hear such prophetic register again, for old truths spoken to new circumstances are new truths. And this is true in Vol. 1 of the journal not just in Paul’s and Dougald’s words, but in those of many other contributors too.

I especially welcome having these contributions written down because, at the festival itself, I was too preoccupied with preparing my own presentation to have taken very much in. I was working with my colleagues, Iain MacKinnon on the pipes and in Gaelic song, and Tom Forsyth of Scoraig in just being Tom. What was programmed as a single-billing became an act spanning three generations. My aim was open the ground to spiritual deepening. If mainstream life has become more and more like virtual reality, our imperative is to reground in essential reality – in the elements of fire, air, earth and water, and in their underpinnings of meaning such as constitutes the Spirit.

At a crucial point in my talk I asked Iain “What is spirituality?” From an alcove high above the audience, he appeared and broke into ancient song. Again, as I dissolved into poetry at the end of my talk, he accompanied with classical pibroch on the pipes. It was a last minute inspiration to have Tom also join us on the floor. We were out of time because earlier events had over-run. His contribution was short but memorable. Holding up a watch, and perhaps mindful too of tight railway connections the previous day, he remarked: “Ever since I have travelled down here I have had to live by deadlines. But where I come from, staying in my small bothy at Scoraig, we live by lifelines.”

Tom, Iain and I have decided to continue this triple-act when we run a week-long session on land and empowerment at Schumacher College this September. But my point in saying all this is that during the festival itself I was pretty preoccupied with people rather than the other presentations. It was not until I got home that the intellectual side really caught up with me. This was the treat that awaited in the Dark Mountain Journal.

As a writer you get something of the measure of your own work. You have to for quality control. For me, the test of how well I’ve written a piece is what I call the Whisky Test – the satisfaction felt on reading and re-reading. Does it slip down like a many-times-distilled and carefully-aged malt whisky? Are its after-flavours evocative? Sea, and peat, and song, and dusky Hebridean … shall we say, “sunsets”? Or is it a little rough on the throat, under-refined, unbalanced, not fully mellowed?

Well, the piece that I contributed to the journal was not bad on these accounts. Called Popping the Gygian Question it’s an exploration of the imperative of Truth (yes, capital T) in challenging times. I approach it by exploring the little-known myth of Gyges in Plato’s Republic. But I have to confess … in my opinion, as assessed not least by the Whisky Test, many of the journal’s other contributions simply outclass my own. There’s just some wonderful work here! True, I didn’t quite get the point with some of the more artsy pieces, but maybe that’s just my own scientific disposition. But many of them, and I mean, many, of the prose essays in this debut volume of Dark Mountain Journal are courageous and inspiring stuff. These reveal the marrow of what Dark Mountain is about. They demonstrate that lifting of the veil on consciousness, giving vent to voices that a person like me has been yearning to be nourished by. Let me give a run down on some of the contributions that particularly struck me.

John Michael Greer provides a fascinating offering on the deep ecology poetry of Robinson Jeffers. I don’t agree with his take on peak oil for the same reasons as George M. named in his talk – namely, varying forms of synfuel substitution from coal especially – but I was moved by his passion, and his delineation of environmentalism into 1st wave recreational environmentalism (national parks etc), 2nd wave sentimental environmentalism (Rachel Carson), and 3rd wave apocalyptic environmentalism which is where he sees us being at now. I disagree where he says, “The function of apocalyptic myth, after all, is to console the unimportant by feeding them fantasies of their own cosmic significance” (p.10). I think Greer misses the point about what spirituality is, but he misses it in a stimulating way, so, thank you, John Greer.

Maria Stadtmueller’s piece, “Hostage”, looks at the Assisi tourist scene through the eyes of St Francis. “Preach to us of poverty, because if we were poor we wouldn’t be here” (p. 21). Bang goes my next bit of spiritual tourism a.k.a. “pilgrimage”. For, she tells the saint, “You went alone out into the winter woods and embraced the feared she-wolf of Gubbio because you knew she killed from hunger. So do we.” Wow. It left me having a discussion subsequently with a Norwegian hunter to the effect that if we, who had both been hunters of wild animals in our time, could choose our deaths when we get old, would it not be fitting to yield to the wolves? After all, David Livingstone told that while he got mauled by the lion he passed into a pleasurable swoon, leading him afterwards to ponder that maybe nature is kinder than “tooth and claw” might cause one to imagine.

Dougald Hine’s interview with Vinay Gupta brought back the quote that I wrote down from Vinay’s talk at the Festival: “The war has already begun and you did not notice because you had already won.” That sums up the surrealism of what is happening in our name in Afghanistan. Same with the simulacrum fate (for those not left bleeding) of Iraq. Vinay shovels heavy shit but does it with a wit that leaves a smile.

Paul Kingsnorth’s “Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist” should be read carefully by Dark Mountain’s critics because it brings out the beauty, and depth, of what motivates the man. It was the motorway protests of the 90s that woke him up just as they massively impacted the consciousness of so many of us “elder” activists today. His honesty is jawdropping: “I look out across the Lake District ranges and … the farmers are being edged out by south country refugees like me, trying to escape but bringing with us the things we flee from … the virtual happily edging out the actual … I know why the magic is dying. It’s me. It’s us” (p. 51). Well Paul, quite so, but with spiritual honesty like that you bring the old English indigenous magic back alive again. As a Scot, I salute that.

Next, and I’m jumping over quite a few here, Dougald Hine’s “Death and the Mountain” profile of John Berger. My goodness, Dougald, in real life you come over as such an easy-going Dylanesque (as in Magic Roundabout) sort of character that I just didn’t realise you were such a grappler with the bowls of life and death as this piece reveals you to be! This is an essay that deals with peasant life, and the observation, as I would surmise it, that it takes place not in 3 dimensions but in 4, because the dead too are part of the community. It’s an area of thought and experience that I’m working on myself with Hebridean indigenous community and the old theological notion of the Communion of the Saints (ho hum!). In contrast to peasant cultures, says Dougald, “our culture lacks a developed discourse about metaphysics,” though “poets are a special case: the poetic licence is a day pass from the asylum” (p. 87). Berger, he says, writes from “beyond the Pale of civilised modernity” (p. 92) because he writes of a worldview in which the peasant “lives publicly and matter-of-factly with the company of the dead, in a way which stands outside what is acceptable as reality among grown-ups in civilised conversation” (p. 90). “Berger’s allegiance to the poor is inseparable from his insistence on the importance of seeing, for – he tells us – only the poor can afford to see the world as it really is” (pp. 92-3). For me there was just so much … to use an expression that Hine borrows from Subcomandante Marcos … “unflinching excess” in this essay. It gets to the roots of what uncivilisation means. It means re-entry into that imaginal realm of the dead, of faerie, of mythopoesis. The restoration of our inner lives as an antidote to the modernist straitjacket of limited rationality and the conceits of postmodernist nihilism.

On to Anthony McCann, and meeting this Northern Irish scholar was one of the highlights of the Dark Mountain for me. His interview with Derrick Jenson, “A Gentle Ferocity” touches on much that is wise about Jensen, but McCann himself is wise to the self-made limitations of Jensen’s friendship with violence. McCann describes how Jensen advocates (but body-swerves practicing) violence against the industrial world. His “anger is directed, too, at those who say there is no room for violence in activism: he enjoys ‘deconstructing pacifist arguments that don’t make any sense anyway’” (p. 108). As an American friend said to me recently, Jensen is an important thinker but his flame doesn’t yet burn clean. His offering stalls as it hits the macho glass ceiling of violence as is so evident in his book, Endgame. As is often the case with violence, it’s tied in with what feels to this reader, at least, like an excessive expression of ego. Thank you, Anthony, for your sensitive exploration of this man who you otherwise admire.

In “Poetry’s Compost” the nature writer, Glyn Hughes, describes how, as an artist in the 1950s, he followed a “back to the land” calling as a spiritual quest. “People ranging from urban artists to farmers continued to tell me that I was romantic and ‘escapist’. My view remained that it was society that was ‘escapist’” (p. 172). Hughes is not naively Luddite. He grants that “it would be graceless for me personally to decry technology” because he has benefitted from it greatly in a medical crisis. But his bottom line is that that we must learn to live much more simply, and that the reconstitution of real art and not its simulacra in TV hyper-reality is the key: “What I am talking about is reality,” he asserts (p. 175). Thus, “We need to look with altered sensibility into a different world; a spiritual one, curiously parallel and visible enough, but curiously unseen. Only such a change in sensibility, such an illumination, would give the strength and energy to adopt a simpler, less commercial mode of existence. This change of sensibility needs to come – from where else? – through art.” To which he wryly adds, “Some hope!” (ibid.). And yet, that self-put-down, whilst modest and “realistic”, is unconvincing: because at a deep level, a prophetic level, Hughes speaks the truth.

On to poetry itself, and Dan Grace’s piece, “An Sgurr” really caught my attention because it is about the Isle of Eigg where Tom Forsyth and I were heavily involved in the 1990s community land buy-out. I love the cosmic longitude with which Grace reflects on the island’s ancient whale-like volcanic edifice, the Sgurr, seeing it as a metaphor for the “whole world”, a place where we come “to finally know/ that we are the ashes of long-dead suns.”

In a long but riveting contribution Simon Fairlie (who publishes that outstanding English journal of land reform, “The Land”) gives the lie to Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons.” The commons were not destroyed by commoners; Fairlie shows that they were destroyed by the forces of enclosure and other commodification that set out to appropriate them. This is the untaught history of England that the English need to know to recover the integrity of their identity. I promise that we Scots will send foreign aid for the project. The English have been successively colonised by Romans, Saxons, Normans, and now the ensuing class system that holds landed and social class power in place. The people as a whole have not been well served “by those Christians who had all along secretly believed that the rich should inherit the Earth” (p. 193). Thanks to Google, says Fairlie, Hardin’s “tosh is no doubt being copied into sixth form essays across the length and breadth of the English speaking world” (p.199). Like we have started to do in Scotland as a prelude to our land reform legislation, England, too, needs to reclaim her history. Only then can her peoples (plural) discover the political and cultural bearings of a post-imperial identity that all – including those who have been colonised – can find sympathy with, rejoice in, and celebrate as “Real England”.

At this juncture, almost at the end of working my way through the Dark Mountain Journal, I’m forming a clear picture of what Dougald and Paul mean by “uncivilisation”. It is not an attack on civil society and civility as such, but on the perversion of civil values that passes for “civilisation”. It is, to borrow from Baudrillard again, a challenge to the simulacrum of civilisation – the setting up of something called “civilised” which is actually a fake. Such a critique of civilisation thumps home in the next essay, which to me is the keystone contribution to the whole collection: Jay Griffiths’ brilliant and courageous “This England.”

Not only does Griffiths write beautifully – something that she shares with most contributors to this volume – but here we see the prophetic eye, the bardic register, honed to its keenest. Her subject is English identity; the ambivalence of why it is that “the English can be either envious of indigenous cultures or poisonously racist towards them” (p. 202). Indigenous English identity has been hijacked by the BNP with its xenophobic narrative. There is a failure to recognise that the common English people’s “true enemies are the odiously wealthy” – those, we might say, to whom the relatively poor pay rent, or its capitalised equivalent as mortgage.

Like several of Dark Mountain’s contributors Griffith cut her teeth in the motorway protests of the nineties. To these exiles from Babylon, she tells us, “the gods” – the gods of the land – “who are never for sale, played” (p. 205). I call Griffiths’ prose “bardic” because it is not the poetry timbre of ditties: rather, it is a speaking to the soul of the people; to their condition. Thus: “The wealthy, if they want to belong, have to return the lands to the Commoners. They won’t, I know, but what they lose, without question, is the true belonging of the human heart” (p. 207). The imperative that faces the English people, like all the world’s peoples on the shadow side of civilisation, is to recover indigenous identity: a connection through the soul with the “gods” or spirit of place. And some thunderbolts those gods can throw: “Indigenous people frequently say that they belong to the land. Landowners claim that the land belongs to them. Ownership is the opposite of belonging and for the large landowners of Britain, the more they own, the less they belong” (ibid.). Wow! Like with Simon Fairlie’s contribution, all I can say by way of a message back to my fellow Scots is, “Up the levels of foreign aid. Make top priority the no-bullshit land-reforming artists!”

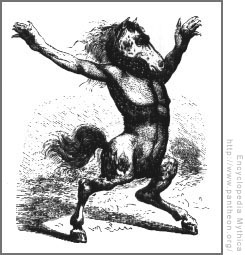

I turn, lastly, to the final contribution in the Dark Mountain Journal – Nick Hunt’s short story set in Victorian Wales, “To the Bone.” It haunts me even a week after the first reading. Hunt describes the mindless attempt by the men of a mountain village to hack to death a water beast called the “afanc”. Egged on by a rumbustious Anglican-sounding Reverend, the afanc has been lured by a beautiful virgin who they’d seated by the lake. Entranced by love it had risen out of the water, laid its head in her soft lap, only to have the waiting men entangle it in chains. These stalwarts then get on with their grim work. The virgin goes home in tears. She’s upset by the whole sordid show. But the men, coming on relentlessly like relays of gold-diggers from far afield through the frosty mist, arrive and pound away, incessantly clubbing the afanc with paddles though its hair and skin and flesh. But they must reach the bone. The Reverend has told them that only with a crack to the vertebrae can the beast be destroyed: the hero’s reward – a kiss from the virgin. And “a kiss” is to say the least, judging by the narrator’s fleeting fantasy.

I do not know about Wales, but in Scottish tradition water beasts, or water horses, each uisge in Gaelic or the kelpies, are omens of impending tragedy that will afflict the entire clan. These warn of the death of a great chief, the sweep of a plague, or of the people’s crushing defeat in battle. The ethnographer, Ronald Black, now retired from the Department of Celtic at Edinburgh University, has said that it is no surprise that the modern wave of Loch Ness Monster sightings began in the 1930s. Documents recently released show that even the local police at the time were convinced of the Monster’s reality. To Black, the clue that yields the cultural meaning to this rash of sightings that set in motion the modern Loch Ness tourist industry lies in its timing. Most of them happened just before the tragedy the Second World War. Many a Highland village was about to be decimated of its youth. Such visionary stirrings of the second sight were precisely what the Tradition would expect to have heralded such an event amongst intricately interconnected indigenous communities. For the Monster of the Ness, and those less famous of other Scottish lochs such as Morar, is not a creature of the outer world. The Monster is an archetypal projection of the inner collective psyche. Here, in a realm of our being human where space and time tails off into that fourth dimension, the future is already present and so the impending terror cannot but break through. This is what drives the raising of the each uisge’s head. It is not she that is truly the “monster”. She, dear thing, is just the harbinger of monstrous events about to unfold.

In his story Hunt tells how the afanc had “dragged its foul body from the murky depths, and laid its hideous head in the maiden’s lap” (p. 227). It is his narrator who imputes foulness, yet the reader cannot fail to notice the gentleness with which it had “laid” its head in the maiden’s lap. We’re told it “couldn’t help itself” at the glimpse of her beauty. Here we see a primal tenderness, beauty beyond the perception of the beast’s civilised antagonists.

In the haunting children’s movie, Into the West, such primal wildness is, in the closing scene at the ocean, revealed in the form of the water horse as spiritual healer. Only then do we realise that the magical white horse, Tír na nÓg, is a mythical beast of the Celtic Otherworld (Tír na nÓg being the Celtic heaven, the Land of Eternal Youth). The horse penetrates the ego boundaries of decayed civilisation and rescues the two little boys, wounded by the alcoholic neglect of their father in a Hi-rise Dublin housing scheme who has lost connection with his position as king of the Irish Traveller folks. Amidst many adventures Tír na nÓg sweeps the boys home to the traveller haunts into the far West. There, in the waves of the ocean, the goddess-love of their mother, lost during the childbirth of the youngest (which is what had broken the father) is restored. The horse returns to the sea and the boys, saved from drowning, reunite with their father, his Traveller indigeniety made whole. The Irish Travellers link their history partly with being pushed off the land during the colonial times. For whatever reason, the British film censors couldn’t hack it. Although the movie is clearly aimed at and magnificently suitable for younger children, it got given a commercially-crippling age-15 certificate. And as I write this, the tears run on my face at the sheer beauty of this story; its deep power when understood in its proper mythological context.

I do not know whether Nick Hunt has any awareness of what water beasts can mean in Celtic lands to the north and west of Wales, but his afanc story perfectly captures the motif. In Victorian Scotland there were several attempts, usually led by landowners, to capture water horses. These included pumping out a loch and trying to bomb a monster by dropping sacks of quicklime into the depths. Like today’s mini-submarine surveys of Loch Ness, none yielded any results that positivist science would have recognised. All made the category error of confusing literal reality with the outward visionary projection of inner archetypal matter.

These are experiences of depth in community with one another that the world of disconnected, individualistic, competitive types of civilisation cannot share. Those who force “civilisation” by violence may have won the sobbing virgin. Like Brutus of Troy (according to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain), they may have won (or seized) the sobbing Ignoge “as a comfort” en route from Greece to Totnes in 12,000 BC when coming to rule Britain. But their achievements are but the shadow side of their own brutality. And so, the archetype recurs. The water monster just won’t tie. What Walter Wink calls “the myth of redemptive violence” plays out over and over again as Moby Dick, or Darth Vader, or Bin Laden, or the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable; and it is satirised brilliantly here in Nick Hunt’s fable of the “afanc”.

There can of course be many readings of a fictional tale, but for my money, what Nick Hunt is trying to say to us here is to stop clubbing wildness to death; to pay heed to the afanc – pure nature wild that sought out love, but revealed to us truths about our own lovelessness. Here we see the depth of Dark Mountain’s summons to analyse and treat the human condition at a depth that is spiritual. To me, this is the calling of what Paul and Dougald have dubbed “uncivilisation”. It is not about unravelling the survival structures of our society. It is a call much deeper than that. It is to put survival structures in place by calling back of the soul.

Been thinking quite a lot about Dark Mountain since first came across the project here. And of John Berger and his ways of seeing.

Now, after reading this thoughtful review, I feel I need to get a hold of Vol 1 of the Dark Mountain journal. Not ‘want’ to but ‘need’ to.

Thanks Alastair.

Dear Alastair,

Thank you so much for your contribution to the Uncivilisation festival – it last a lasting impression on me, as I began to explore here:

http://www.darkoptimism.org/2010/06/03/the-art-and-music-of-our-worlds-predicament/

I look forward to when our paths next cross.

That’s really encouraging to hear, Shaun. I will look forward to meeting you face to face sometime. May I add that I wrote this review in a hurry and did not think, at the time, to Google “afanc”. I thought it was just a made-up word. It turns out that the Afanc is, actually, the Welsh equivalent of the Scots water horse.

It also turns out that my literary engagement with the afanc was, indeed, to be a harbringer of bad news to the clan, and in ways beyond what I can share on a public website. But in the early hours of Sunday morning my colleague, Tim Edwards, formerly manager of the Social Inclusion Partnership here in Govan, Glasgow, suddenly passed away.

In my “Popping the Gygian Question” contribution to the Dark Mountain Journal on p. 107 I discuss Plato’s questions about the truthful life as being linked to the “question as to whether good can ever come from knowledge acquired, or actions engaged in, by deceit.” In fact, that particular turn of phrase was given to me by Tim when I was discussing this point with him at the New Year. He was one of the main people I discussed the essay with as it was taking shape and therefore partly responsible for its shape.

I have posted a version of the essay on my website with a dedication in Tim’s memory. He

was a champion of urban liberation theology and strong in his service to, and his standing alongside with, the poor. He strongly encouraged my own work and recently, when I ran “A short course in liberation theology” in Govan, it was his constant prompting that was partly behind what encouraged me. Tim Edwards did a huge amount to help us to get the GalGael Trust properly up and running including pointing government money our way and directing us towards the funding that allowed us outright to buy our premises at Fairlie St. in Ibrox.

In short – Tim Edwards – R.I.P.

“I think Greer misses the point about what spirituality is, but he misses it in a stimulating way.”

I think that assessment is unfair, especially given the fact that Greer is not only active in a religious movement but is also occupies a prominent leadership position (Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America) within that same movement.

A more accurate statement would be that Greer’s particular neodruidic spirituality is not one in which an eschatology figures prominently. Thus the narrative of apocalypse does not carry much meaning for him, any more than it would to, say, a Shintoist or a South American shaman or anyone who does not subscribe to an Abrahamic (and specifically Christian) worldview.

It is not the case that such people — who incidentally are quite numerous and until recently constituted a majority of the earth’s population — “miss the point about spirituality”, but rather that their spirituality centers around other narratives than that of apocalypse. These narratives frequently feature a cyclical, rather than linear, view of time and the cosmos.

This may seem to be a minor quibble, but it is precisely the linear narratives which have their roots in the Abrahamic religions (and Christianity in particular) which have brought us to the point where we are today. What was that that Einstein said about not being able to solve a problem using the same type of thinking that brought it about?

These themes are explored more in depth in Greer’s book The Long Descent, which I urge you to read to place his comments more in context.

I second the motion (Zenarchist). The Long Descent is an important piece of work, and one I have done my bit to circulate.

You make an interesting set of points, Zenarchist, and I do agree with you about the circularity of time, though I would see it more in terms of spirality, since I think that time does also have direction – geological strata are evidence of that.

However, may I suggest that an apocalyptic perspective does not necessarily imply an “end of time” teleological one in the sense that I think you are implying? I am using the term apocalypse in its technical sense, which means “to remove the cover”, “to unveil”, in other words, to see the inner meaning of an issue or of the times. That is why I questioned Greer’s statement, “The function of apocalyptic myth, after all, is to console the unimportant by feeding them fantasies of their own cosmic significance.” I think that can be a malfunction of apocalyptic myth, but it is not a full understanding of it.

For more on this, see my Foreword to Stefan Skrimshire (ed) “Future Ethics: Climate Change and the Apocalyptic Imagination” – which, as it’s part of the free-view pages, can be read online on Amazon at:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Future-Ethics-Climate-Apocalyptic-Imagination/dp/1441139583/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1279652671&sr=8-2#noop

I would have to say, however, that it was only in the course of researching apocalypse once Stefan had asked me to write this foreword that I came to the full significance of the term as it is used by theologians.

Best wishes, Alastair.