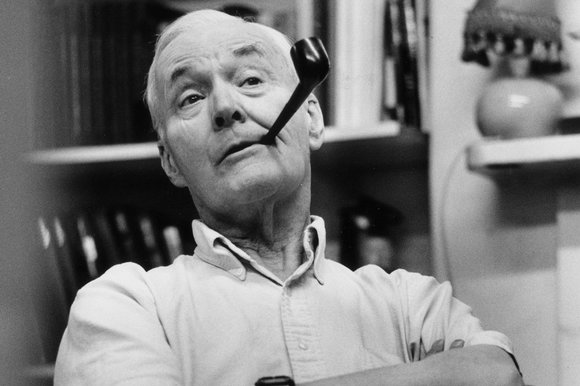

Tony Benn: the Prophet Outcast

Dare to be a Daniel,

Dare to stand alone!

Dare to have a purpose firm!

Dare to make it known.

It is no surprise that Tony Benn, who modelled his socialism as much on the teachings of Jesus Christ as on any left-wing economics textbook or materials doctrine, should have chosen this old Protestant hymn as the title for his memoir. As his mother told him, the Old Testament was the setting for a clash between the kings, who had power, and the prophets, who preached righteousness, and that he should always choose righteousness over power. For a long time, Tony Benn sought power – an MP at the age of 25, renouncing his right to the title of Viscount Stansgate so he could stay in the House of Commons, Harold Wilson’s Minister of Technology, then Secretary of State for Industry in the second Wilson Government – but when he had ascended the ladder, and saw the subtle corruptions and perversions of how he believed the constitution should work, and saw Labour government after Labour government abandon the policies they were supposedly elected to implement, he turned from the ascent and chose to become a prophet. A little too enthusiastically his opponents would add: but this was a man of whom many of his peers had believed could well become Prime Minister, which is a weighty laurel indeed to reject.

The cynical would note: a prophet of what? The final years of the twentieth century were littered with the wreckage of Tony Benn’s dreams.

Across the globe Thatcher’s brand of capitalism seemed triumphant (it is doing rather less well now, but no systematic alternatives of the type Benn preached have emerged to prominence). The UK was still very firmly inside the European Union, if a little uncomfortably seated (but what resistance there was came from the right, not the left); the American military alliance still held firmly; nuclear weapons remained firmly ensconced at Faslane. Socialism, once a mighty political and economic movement shouted from the rooftops of the world, now seemed reduced to the status of a secret pass-code for a certain breed of political obsessive. This was very much not the world he had fought for: one of economic and social justice, of the redistribution of wealth and power to ordinary people, of military disarmament and the accountability of power. However, to take this view is to misunderstand the meaning of “prophet” in the Old Testament: the prophet is not necessarily one who can predict the future, but one who calls society and power to account for their corruption and folly. And Benn did this better than almost anyone.

His politics were suffused in the legacy of the past: he was one of the old English non-conformists, as was his contemporary Michael Foot, well aware of the debt present generations owe to the strivings of their forebears for freedom and equality: the Levellers, the Chartists, the Suffragettes. Their mental outlook was best summarised by John Stuart Mill when he warned against “the tyranny of prevailing opinion”: to be a Daniel meant to stick firmly to your principles and to articulate them, even if you were in a hopeless minority. Freedom above all meant freedom for the dissenter; otherwise it was no freedom at all. This current of free-thinking was grafted on to twentieth century Labourism, which in some ways was an uncomfortable cross-breed. The Labour movement was fundamentally based on the principles of solidarity and collective responsibility: the strength of the workers lay in their unity, and any divisions could only lead to disaster.

Some therefore viewed middle-and-upper-class individualists like Benn as selfish egotists who had no sense of duty or loyalty to the wider movement, and who would happily undermine the cause for the sake of their own conscience. An earlier Christian socialist, George Lansbury, leader of the Labour Party in the mid-1930s, discovered this to his own cost in 1935, when Ernest Bevin destroyed his pacifism at Labour Party conference over Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia: “It is placing the Executive and the Movement in an absolutely wrong position to be hawking your conscience around from body to body asking to be told what to do with it” and ‘He has been carrying these martyr’s faggots around with him for years. All I did was to set a light to them.” Benn, who came within a whisker of becoming Deputy Leader in 1981 in a bitter and acrimonious fight against Denis Healey, may well have lost out due to fears of his divisiveness. The right of the party certainly never ceased to blame him, and his unwise and naive choice of friends, for Labour’s 18 years in the wilderness.

And yet, his principles and political creed made him beloved as well as reviled, and not just in his final years when he became the nation’s favourite grandfather and, in his own words, had become “harmless”. It was not only because he stood for causes which, in their time, became mainstream, such as anti-colonialism, anti-racism and talking to Sinn Fein, or his prescience about the damaging economic impact of Thatcherism or the Iraq War. It was not just because he was “the Persistent Commoner” who successfully threw off his peerage and paved the way for lords and ladies to renounce their titles. It was not solely because of his magnetic personality.

It was because, in the words of one of the many books about him, he articulated a “heresy” about the UK constitution and economy which many know to be true but is rarely admitted: that Britain’s democratic structures are flawed. He believed so firmly in the creed of representative democracy and the sovereignty of parliament that he was genuinely dismayed to discover their true inner workings (as laid out in his voluminous sets of diaries), and how easily they could be subverted in the pursuit of wealth and power. He grew sick of political parties elected on the basis of a manifesto which was promptly ditched once in power; he saw rank and file party members shut out of effective decision-making by a self-satisfied complacent gang of jobs-for-life professional politicians; he saw power leach away from democratically elected institutions towards international bodies like the European Commission, and multi-national companies. He took the lazy boosterism that “the British political system is sound” and shot it to pieces. He formulated five questions about power:

1) What power have you got?

2) Where did you get it from?

3) In whose interests do you exercise it?

4) To whom are you accountable?

5) How can we get rid of you?

…and found, with the development of quangos and special advisors and the devolution of decision making to technocratic bodies and the immense power of corporate lobbyists, not to mention the continued existence of the entirely unelected House of Lords, that the questions could be answered less and less satisfactorily as the decades went by. Furthermore, Benn’s efforts in this field were no entirely unrewarded: the fact that all political parties now elect their leader from the wider membership rather than merely through the elected politicians, is partly down to him.

Additionally, Benn represented the road not taken in the economic sphere. The crisis of the post-war Keynesian settlement in the 1970s was eventually to drive the developed world right, towards free markets, free trade and globalisation: Benn drew the opposite conclusion, inspired partly by Jimmy Reid’s Upper Clyde Shipbuilders work-in, and saw the need for greater economic regulation and management, with greater workforce representation. National planning boards, state shares in private enterprises to guide investment, support for workers’ cooperatives, and most interestingly, state shares in investment and planning in the nascent North Sea oil industry. However, the political and intellectual trends were against him, the economic context was very inhospitable, and Thatcherism was to sweep these tentative steps away for ever. One can sneer at his economic heresies as outdated, left wing dinosaurism, but the alternative has left the UK with huge levels of household debt, chronically low wages, the severe decline of manufacturing, a very significant balance of payments deficit, persistently high levels of poverty and inequality, economic growth driven by house prices and financial bubbles, and low levels of productivity and research and development, as well as regionally unbalanced growth and whole areas blighted by unemployment due to the collapse of industry. In many areas, particularly regarding unemployment and poverty, the UK has actually regressed since the 1970s, and economic growth rates in the 50s and 60s have outpaced anything since. The current government’s idea of promoting economic growth is to re-inflate the housing market. And Scotland has missed out on the national benefits which North Sea oil provided Norway with. Given the on-going economic crisis, some of his ideas may yet prove worth listening to.

The American journalist George Packer describes the period between the 1930s and 1970s in the US as “the Roosevelt republic”. The UK’s version could perhaps be called “Attlee’s commonwealth”: it was characterised by strict economic regulation, state intervention, high personal taxation, powerful trade unions, a strong welfare state, the virtual elimination of involuntary unemployment, significant declines in poverty and inequality, a broad-based growth in living standards, a political consensus around the above, and a certain austere style. Most of this has gone now, including virtually all of the political class who defined it – Denis Healey is among the last survivors. Those elements that survive, such as the NHS, are slowly being picked apart by the present government (at least in England). Some changes are for the better. We would not want to go back to that generation’s level of female employment, or its relative lack of personal freedom, or its stop-go economic policy, or its industrial strife.

However, the regime which replaced it has wantonly destroyed many of the gains of previous generations: indeed it may end up destroying the United Kingdom itself. Dissatisfaction with the political class is high, yet no alternative system or world-view has established itself as a contender for people’s hearts and minds. The kings have bought off the prophets: power has corrupted righteousness. This is a political generation for whom access to power and its rewards are everything, and being a lone rebel is less attractive than ever before: we have almost lost the Daniel mentality altogether. This is a pity. A healthy democracy and free society requires dissent above all; it needs those who provide an alternative point of view, those who warn against the perils of the cosy consensus, those who are prepared to fight for causes which are at the time of minority appeal, even if it comes at the cost of their personal success. It needs a profound awareness of our political legacy: it needs men and women like Tony Benn, who can inspire millions to fight for freedom, equality and justice, and to hold the powerful to account. Let us hope that we do see his like again.

RIP !

In the excellent social history ‘Seasons In The Sun’, by Dominic Sandbrook, Tony Benn does not come out looking good (unlike Jim Callaghan, who appears to have been much more skilful and much more liked than I realised at the time). Totally off the scale, in fact.

Tony Benn’s only significant success was the promotion of Tony Benn and he was no friend of Scottish constitrutional change.

Not EVERYTHING in the universe should be seen through the prism of Scottish independence

You don’t need to agree with every single policy Tony Benn backed to recognize that he was a man of great integrity and compassion.

And he is absolutely right when he said in the video Bella posted here on the day of his passing that “there is no final victory and there is no final defeat”, that each generation has to fight the same battles again and again. He was a tireless worker for social justice.

The neo-liberal paradigm will pass, and we can lead the change from Scotland. Let’s remember the wider context. Forty years ago the cranks were the neo-liberals, the whole of Europe was Social Democratic, even the right. The European Union was an invention of centre right Christian Democrats, the Germans especially, who, having witnessed the horrors of two world wars, made full employment and consensus politics a priority, the number one priority. The rise of neo-liberalism and the decline of Christianity in Europe may be inter-related.

Now we are run by people who have no historical memory, who only look at the numbers, whose policies create huge social divisions and dire poverty and so, as has always been the case, we are seeing the rise of the extremes again in Europe. The National Front in France, UKIP in the UK, Golden Dawn in Greece for example.

And yes, we do need “prophets”, we need dissent, and in Scotland I think we have plenty of them. It comes with the terrain, the terrain of the underdog.

I enjoyed the article, Daniel, thanks for posting.

Some of the limitations of Tony Benn’s politics for Scotland were discussed here: http://wingsoverscotland.com/a-letter-to-tony-benn/

Given his love of parliament (Westminster) and his lack of any European impulse, it’s no surprise that he should have been against Scottish independence. But he could have played a good role in the future, when England comes to set up its own parliament.

Not EVERYTHING in the universe should be seen through the prism of Scottish independence.

Sure. But Scottish independence is a good prism through which to look at British poltics now.

The call for the ‘spirit of 1945’ (see Ken Loach in the Guardian today), which Benn also made, is another aspect of this. It’s part of the cult of Britain. This had a real and successful energy during and after the Second World War. But that energy ran out a long time ago.

In these ways Tony Benn wasn’t a nimble or progressive thinker – rather someone who knew some big truths and hammered away with them, even after the context had shifted. For example, he kept on talking about ‘Yugoslavia’ years after it had split apart, and came close to defending Milosevic’s Serbia.

Robin Cook (not a friend of Scottish independence) or Ken Livingstone could be examples of UK Labour figures who are/were nimble thinkers – more open-eyed about the limitations of Westminster than Benn, and sometimes more successful than Benn in playing the political game.

strangely enough the only other time I heard that poem was at the funeral of Andrew Boyd in Belfast, NI (author of among other things Holy War in Belfast) . He also was a socialist in the same tradition as Benn

Daniel Wylie lets Tony Benn off a little too lightly. He looks back favourably on the post war settlement; Attlee’s commonwealth but ignores the fact that this was part of what Benn was, in the 1980s, rebelling against.

In his diary (20th February 1981) Benn tells Keith Joseph, another ‘prophet’, that ‘the last 35 years have been a disaster.’ The Labour Party finally realized he was leading them to oblivion – where they would be, in Eric Hobsbawm’s words, ‘a marginalized soclialist chapel.’

When he stood for leader at the end of the 80s, he got 11% of the votes; this against Neil Kinnock.

Benn did not choose to become a prophet, rather than a practising politician. The latter choice was no longer available.