The indyref, democracy, the political class and partythink

With just days to go until the Scottish independence referendum, the country has changed. It’s never felt like this before. The wonder of democracy shines everywhere.

I’m voting yes, and I’ll explain why in a minute. But you’ll have read dozens of these pieces by now, and almost certainly of superior quality. Perhaps of more interest to you may be my reflections on the impact of the referendum on the way we do politics in the future. I set these out at greater length below and you’re very welcome to have a read. I’ll explain why I think politics has become detached from real life, and how the referendum experience has helped to reverse that. I hope it’s not too dry. No academic study is required!

Full disclosure to begin with. I studied politics at university. I have never been part of any political party and have never had a political role of any sort. I’ve voted in every election since I turned 18 in 1999. Until 2010 I voted Labour in UK elections and also gave Labour my first vote in Scottish elections. I voted Green in the 2010 General Election and SNP and Green in the 2011 Scottish election. I don’t know how i’ll vote in future. For the avoidance of doubt, I’m not a tub-thumper for the SNP, but I think they’ve governed Scotland very well since 2007.

I don’t think I’m partisan, so I hope you’ll read my essay in that spirit.

Anyway, here’s why I’m voting yes, and after that why I think the referendum has transformed Scottish politics regardless of the result.

Why I’m voting yes

I never really thought much about independence when I was growing up. At university I studied Scottish politics and remember that opinion in favour of independence had been stuck at about 30% for generations. As such, independence didn’t occur to me as something particularly likely to happen. So I thought about other things.

My political awakening was in 1992 when, aged ten, I wandered in for breakfast to find my mum in floods of tears, inconsolable, because the Tories had won the election. I didn’t understand what had happened but it had made my mum cry, so I took it upon myself to find out. Fast forward a few years and i graduated with a politics degree, still not really sure I understood much that was going on.

That first lesson in the importance of politics stuck with me though. Tories = my mum in tears, so that’s not on.

Like most people in Scotland, my hopes were invested in the Labour Party as a means of protecting us from the Conservatives, and like many people I was at first very happy, and then eventually very disappointed with them. The joy of that sunny morning in 1997 seemed like it happened in a different dimension when we were marching against the war in Iraq on 15th February, 2003.

I’ve often thought about the people who marched that day. That would have been the first and last time most of those people did something like that. I hoped at the time that the February 15th movement would grow and infuse our civic life. But it dissipated immediately. Until now.

It feels to me as if the people who marched against the war, and who experienced for the first time what it’s like to break out of the straitjacket of formal politics, have reconvened as the Yes campaign. The energy, imagination and positivity is back. I’ve never felt so inspired in my life.

Once it became clear that there would be a referendum, I began as a “Yes, if…” I wanted Scotland to be independent if we did politics differently. More of the same, just closer to home, wouldn’t really motivate me. Wonderfully, the Yes campaign has been a kaleidoscope of original, brilliant ideas. So I’m on board with that.

The Scotland I want to live in is nuclear-free. It has a balanced and sustainable economy. It guarantees legal equality and works towards social equality. It doesn’t treat the Highlands and Islands as an afterthought. It decides how much of the budget should be spent on education and health. And it looks outward to continental Europe and the Nordic States.

These seem like entirely achievable aims in an independent Scotland, but they are almost certainly all impossible as part of the UK.

I don’t have a problem with being British. It’s fine. I got as emotional as everyone else when Farah won his gold medals in the Olympics and I don’t expect to stop supporting Mo when he runs for the United Kingdoms in future major championships. I don’t think anyone will be required to either. I’ve got relatives who identify incredibly strongly with Ireland, despite never having lived there and not having an Irish passport. Our identities are more secure than some commentators would have us think.

Would I give up my claim to Britain’s shared history in favour of a fairer and better Scotland? I don’t think I have to. I’m voting yes and retaining my fascination with British political history. I’m voting yes and still supporting the England cricket team (yes, really). By voting yes I’m not turning my back on Manchester United (I can hear your hackles rising, dear reader). Supporting independence does not mean somehow abandoning the working class in Manchester or Liverpool. They’re still our brothers and sisters.

I’m very comfortable with my British heritage. I’m also clear in my mind that Scotland is a political community with shared priorities that are not popular in Westminster.

What struck me about the STV debate (the group debate between Sturgeon, Harvie and Elaine C Smith, and Dugdale, Alexander and Davidson) was the deep consensus between the Labour politicians on one side and the Yes campaigners on the other. They were fighting over who cared more about eradicating poverty. That resonates with me experience of working in the education sector: it is taken for granted in Scottish civic society that you care about social justice. These conversations simply do not happen in Westminster. As such, I think it’s time we pursued our distinct political path.

But to be clear, what I’m voting for, and what I think the Yes movement is campaigning for, is legislative independence.

This isn’t about nationalism, as commonly defined. It’s certainly not about the English (seriously, has anyone heard anyone even mention England during their independence chats?). It’s not a rejection of shared history with the rest of the UK. It’s about creating space for our different policy priorities to be pursued freely.

Most of the seats in the House of Commons represent English constituencies, where the policy priorities are different. I don’t think anyone could disagree about that. Therefore, the only way to form and maintain a government in the Commons is to appeal to the representatives of those seats. As such, the policy priorities of Scottish representatives are never going to be decisive. Therefore, the only way to pursue our policy agenda is by shifting the instruments of government away from London. To me, that’s literally all that this is about.

We can govern ourselves differently (I wouldn’t use the word “better”; this isn’t a competition) and still be pals with our neighbours. We already vote completely differently from the rest of the UK and seem to get on fine. We’ll all get used to it.

Will it be a painful transformation? I live in Scotland and it doesn’t look to me like a country lacking in able citizens or marketable commodities. I think we’ll do fine. I won’t pretend to be an expert economist, but in broad terms I haven’t seen too many countries with balanced, sustainable economies that have suddenly been ruined.

When I was a postgraduate student I was asked to deliver a presentation on international politics. I left it to the last minute, as I used to do, and found myself typing at 6am having got up really early to finish my task. While I was typing, George W. Bush was confirmed as US President for a second term.

When i emailed my finished piece to my tutor I mentioned to him that I was struggling to motivate myself to deliver the presentation; it suddenly seemed pretty inconsequential in light of that morning’s developments in Washington. His reply was one of the wisest pieces of advice I’ve ever received.

“In politics,” he said, “nothing is ever as good as you hope it’s going to be, but at the same time nothing’s ever as bad as you fear it’s going to be”.

So I’m ignoring the doom-mongers, and maintaining my distance from the utopian fantasists, and voting Yes for a country that will be much the same, but without the lengthy periods of misrule from Westminster.

A country, in short, where no one will come down for breakfast to find their mum in floods of tears because we’ve got another government we didn’t vote for and who don’t understand us.

Why the referendum changes Scottish politics forever

But enough about me. What will the longer-lasting consequences of the referendum be, regardless of the outcome? In the rest of this piece I want to set out some ideas about the way we are governed.

I begin by presenting the ideas of an Austrian-American theorist called Joseph Schumpeter, who is associated with the ‘elite theory of democracy’. I want to argue that his model describes very well the way the political agenda is currently controlled.

I explain this with reference to Peter Oborne’s ideas about the so-called political class, before explaining how the structure of traditional political parties serves to stifle political discussion. I finish by contrasting this with the models of participation that have characterised the referendum campaign. Enjoy!

The elite theory of democracy

Joseph Schumpeter is an oddly forgotten figure today but his influence in the fields of economics and social theory was significant for long periods in the second half of the twentieth century. He remains interesting to me for some ideas he set out in his best-known book, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.

Schumpeter’s ideas are central to what is known as the ‘elite theory of democracy’. The significance of these ideas for me today is that I think Schumpeter described the contemporary Westminster system with chilling foresight. I’ll sketch out his ideas briefly (playing fast and loose with the details in order to convey the general thrust).

For Schumpeter, the business of government is too complex, resource-dependent and time-consuming to be accessible to the majority of the populace. To run for public office you require the time and inclination to educate yourself about the issues, as well as the contacts to gain a nomination from a political party and the resources to maintain your status in influential social circles. In Schumpeter’s view, most people won’t be in a position to achieve any of this.

The business of government, therefore, is best left to an elite, comprising those elevated individuals who do in fact have the intellectual and socio-economic resources at their disposal to pursue a political career.

This perhaps doesn’t sound hugely edifying. However Schumpeter stresses that the general population still have a crucial role to play in politics: they choose between different factions of the elite when they vote in elections.

As such, power is transferred between parties following free elections. This is the ‘democratic’ part of his ‘elite theory of democracy’. At the same time there is no danger of power falling out of the hands of the elite, because the options on the ballot paper (the parties) are just different groupings from within that elite. That’s the ‘elite’ bit of the theory.

Now, there are a number of things wrong with the story Schumpeter tells us and you’ll be able to think of many of them right away. I prefer to think of Schumpeter’s model more as a metaphor than an actual description of reality. Either way, I think Schumpeter can help us provide some context to both the widespread contemporary hostility to Westminster, and to the enormous popular engagement with the Scottish independence referendum.

***

The political class

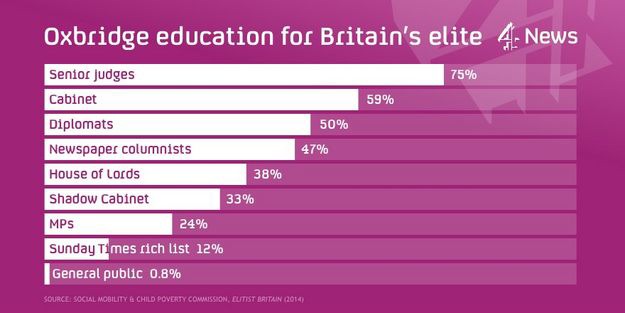

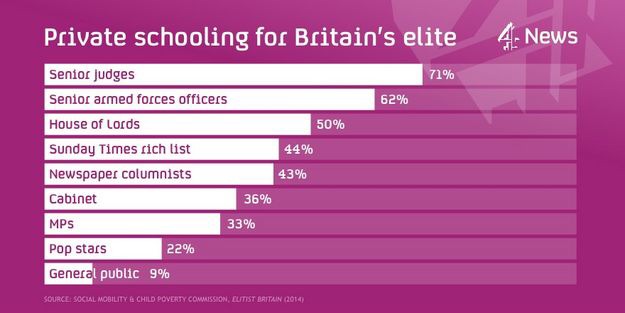

It’s not really a secret that the most reliable route into the corridors of power in the UK is via the private school sector and Oxbridge. Arecent report from the Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission produced figures on this that were elegantly summarised by Channel 4 News as follows:

(No copyright infringement intended, Mr Snow! Hope you don’t mind.)

The link from Oxbridge to the cabinet or senior judicial roles is particularly striking, I think.

Now, we could stop here and conclude that Schumpeter is correct: we’re run by an Oxbridge elite.

But is that the problem with Westminster? I’m not sure it’s as simple as that. I actually think the governing elite that has eroded faith in the political process is considerably broader than the Oxbridge alumni who attend cabinet.

The journalist Peter Oborne has, for me, captured the essence of this elite in his book The Triumph of the Political Class.

Crucially, the political class isn’t actually a social class. This isn’t a matter of class politics. We can conceptualise the political class better if we think of it as having turned into a distinct sector of the economy, like agriculture or academia, with it’s own internal values and rules.

Working within this sector we find:

• politicians, elected or with aspirations to become so;

• staff from the private offices of these politicians;

• employees of political parties; and

• political journalists.

And so we find ourselves here in the domain of the Westminster village. You’ll no doubt have seen The Thick of It and chuckled at the mutual antipathy of each of these groups, as captured masterfully by the great Armando Iannuci. However what is perhaps less immediately apparent but even more significant is their mutualdependence. The cottage industry that is Westminster relies on each of these groups of workers reinforcing the constructed reality that what they do matters.

For example, politicians rely on the media to gain exposure for themselves. That next leadership bid won’t go anywhere without a bit of air time, after all.

Meanwhile, party officials rely on the media to gain exposure for their policy initiatives. After all, there’s little chance that those exciting relaunches would be noticed by the voters without those now-familiar stage-managed media opportunities in front of the party faithful.

And lobby journalists rely on leaks from private office staff to give them stories. What would we read about if there were no “splits” to pour over exhaustively?

(The phone-hacking scandal revealed that close social links also existed between these political workers and certain echelons of the police. But I won’t get into that here.)

Now, I would doubt very much that a high proportion of the political workers orchestrating this went to Oxbridge. I’d also suggest that they work extremely hard for (in the main) not much money. In fact, I think you’d like these people. I know some of them and they’re lovely. They’re definitely not a bunch of Old Etonians, so this isn’t a social class thing.

Nevertheless they are part of a political class that has, through the way it operates, distanced the population from politics. Politics is something that happens elsewhere, mostly on the television, between people the general public never meet and with whom they have nothing in common.

And if you live in Scotland, the disconnection between what is seen as important in the political class’s bubble, and what actually matters to voters, verges on the surreal.

***

Partythink

I will illustrate the problem by painting a picture of life within a political party. For the sake of argument we might call it, well, the Labour Party.

Put yourself in the shoes of a new covert.

You’re passionate about social justice. You want to devote your political energies to eradicating poverty and building a fairer society. So you decide to join our hypothetical Labour Party. So far so good.

You attend party events, do a bit of canvassing, attend the annual conference and eventually decide you want to do more. You’re so committed to helping people you decide you’ll run for election.

The party has a nationally-agreed policy platform. You’re happy with it, in the main. Maybe a few points of detail at the edges that you disagree with, but you can live with it. And so you promote this range of policies passionately on the campaign trail, taking care to hold the line even on the bits you aren’t totally persuaded by.

And you win! You’re an elected representative of the people whose lives you want to improve. At this stage you find yourself participating in endless debates and discussions with people from other parties. They seem to disagree with everything you say. They must be mad, or in the pockets of sinister interests to say the things they do. So you fight back and defend your party and your policies with every ounce of energy you have.

Around this time you make a mistake. You express a personal opinion on an issue when a constituent asks you a question in your surgery. The constituent turned out to be a journalist, and your opinion wasn’t the same as the party’s. You’re called in to a meeting with the central office and reminded of your responsibilities. But they appreciate your work and they’re happy to let this one slide, as long as it doesn’t happen again.

And then you get promoted! You have an official brief. You learn the party’s position on your given portfolio and you promote it with passion and energy. And still the other parties disagree with everything you say and do. What’s wrong with these people?

Every day, after an exhausting barrage of attacks from other politicians and stupid questions from journalists you settle down with your colleagues. Everyone else must be mad, you agree. You’ve grown to really like your colleagues, and you’re going out with one of them. It’s nice to feel that you belong, and that there are other people around who aren’t corrupt and brainwashed like the people in other parties.

And then your party takes a position on an issue you were never really all that bothered about. Let’s imagine this is the independence referendum, just for argument’s sake. If you’d thought about this issue in the past you were broadly in favour of independence, but it wasn’t really on the agenda. The party is insisting that all of its supporters, activists and elected representatives should campaign for a “no” vote. You’re comfortable with that, although in truth you don’t really have a strong opinion on it either way.

Besides, the last thing the party needs is a split. You’ll never hear the end of that from journalists, or other parties, because clearly everyone in a party must maintain the illusion that they all have exactly the same opinion on every single issue.

But look who’s on the other side: it’s the people who disagree with you all the time about absolutely everything. Those idiots. If they’re for this then you’re against it. And as for that leader of theirs…

And before you know it you’re on Twitter and Facebook every day, rejoicing in the support of people who you wouldn’t usually expect to find on your side. Like business leaders, for example, or newspaper columnists from another country.

You’re really busy during this period, because the party have you out on the stump at all hours, plugging away at persuading voters to agree with you. You’re tired. So when you have a minute to yourself and you see that lots of people on social media seem to be attacking your party, you maybe rise to the bait faster than you would usually. If they’re disagreeing with you then they must be in league with that party who hate everything you do. They must be nats. So you have a pop at them, telling them exactly what you think of their narrow nationalism.

But you’re increasingly aware that there seem to be an awful lot of them about these days, these nats, these followers of that awful man who disagrees with everything you say and do. And they keep answering you back, saying they’re not nationalists, and they don’t actually like that awful man, and some of them used to agree with everything your party did.

In fact, these people who won’t shut up all seem to have completely different opinions from each other. At times it feels like the only thing they have in common is they’re hostility to you. And it’s not as if you haven’t been trying. You’ve been working every hour of the day for months! The party has been sending heavyweights onto the BBC and briefing all of the important journalists for ages now. And still these people don’t get it!

What exactly is going on out there?

And then out of the blue, your grandad phones. He sounds a bit nervous, as if he’s got something to tell you. Eventually he comes out with it.

“I’m sorry son. I know you won’t like this, but I’m voting yes. I was a bit worried about telling you because I know how hard you’re working. I’m really proud of you, but I don’t actually agree with you on this one. We can agree to disagree.”

And then it hits you. Your grandad used to talk to you about independence, back when you were wee. During the Thatcher years. He used to say the only hope for Scotland was to make sure we never got another Tory Government, and the only chance of that was as an independent country. You were too young to understand the issues but you remember his conviction.

Hang on, grandad was in the Labour Party! And he’s always talking about how much he hates that awful man from that other party. He’s the least nationalist guy you know – a true internationalist trade union activist. How can he agree with them?

At least your other grandad would have been on your side. He was also a Labour man. When you joined the party he told you about his activist years. He’d go along to the Labour club and often meet the local MP at the bar. The MP would hold court, telling everyone in the room about politics. That’s where he got his political education. He was proud that you were in the party too. You’d learn a lot from the older guys around you.

So who is spoon feeding these yes voters? They don’t seem to be part of any party at all? Where are they getting their graphs and figures and ideas from? Who’s briefing them on this stuff?

And why do your answers work in front of BBC journalists, only for you to be ripped apart by people who speak to you in the street or reply to you on Twitter?

And why are they always really funny when they lampoon us? They look really happy. They look like they’re having a total blast. Everyone on your side sounds quite angry.

Then one of your colleagues has a wobble. He admits to you that he would vote yes if he was allowed to. He thinks the party should have let people make their own minds up rather than campaigning on one side.

You worry about this all night. The next morning you ask your other half what they think you should do. Should you tell the central office? You’ll be showing your commitment and loyalty to the party if you do. But your colleague is a good man and you don’t want to get him into trouble.

You grab your things and go outside. This politics lark is different from what you expected.

**

The beginning of the end

This is how the political class lost Scotland.

The elite that governs us is reinforced by a political class full of people like the hypothetical chap sketched above, who play by the rules of the game.

A crucial rule is: no splits. The political class has convinced itself that the voters can’t cope with parties comprised of people with different opinions. As such, the party line must be held and no compromises offered in any discussion, interview or debate.

As such, if you want to achieve anything in a political party you must sign up to the programme. You’ll be binned if you don’t. And so the opinions that can be aired in the political sphere become narrower as party members censor themselves. After a while this becomes second nature.

This works fine for a Newsnight debate on crime, for example, but it backfires in two crucial situations, namely general elections, and the independence referendum.

In a general election campaign, the emphasis on party discipline serves to alienate the electorate. For years, voters have held their noses and voted for particular parties, not because they were convinced by their policies but rather to keep the others out of government. This can motivate voters for a while but it won’t keep them forever.

And in the context of the independence referendum, the parties just look redundant. If you’ve spent years voting Labour just to prevent a Tory government, but without ever agreeing with the Labour policy platform, the liberation of the referendum experience is exhilarating.

People are, for the first time in their lives, being given space to think freely. They are being allowed to dream. And they can discuss the issues without having to hold a party line, and without an alternative party line being rammed down their throats.

People are thinking about politics rather than responding to electoral imperatives. And through social media, and by speaking to people in real life, citizens are accessing information and exposing themselves to ideas that are never acknowledged by the political class.

As I have argued, the political class is actually a distinct, self-reinforcing social group, comprised of people playing a game called politics and maintaining a monopoly on ideas. Its members, on all sides, are used to a top-down dynamic where parties agree a line, their footsoldiers defend it, and everyone rejects conflicting evidence or opinions as a matter of principle.

That might work on Newsnight, but it doesn’t work in real life.

The consequence of this has been amusingly apparent in recent days. In response to the sudden narrowing of the polls, the political class reacted. The trouble is, it did so according to its usual practices – briefing journalists, rejecting conflicting opinions and telling people what to think. It gave voters the party line. Do this. These are your instructions.

At the time of writing, with a week until the vote, it’s difficult to predict whether this intervention will coincide with a No vote. Even if it does, this is still a watershed for Scottish civic life. Because thousands, perhaps millions of people have had the opportunity to think about politics without constraints or censors. And they’ve connected with sources of ideas and data that they didn’t know existed before; ideas and data that differ markedly from the ideas and data presented as the truth by the political class.

Just as importantly, many of them have been part of a diverse and pluralistic movement, the campaign for a Yes vote, that isn’t managed from above. The yes campaign is a bundle of spontaneous acts by people with no axe to grind. People have experienced what it feels like to participate in non-hierarchical, open politics. That cannot be undone and these people cannot be governed in the same way again. The processes of politics have been exposed and found wanting.

Thousands of people (yes and no voters alike) have realised that you can have an enriching and respectful conversation about politics, that opens your mind and helps open the minds of others – except when you are talking to a member of the political class.

I described Schumpeter’s elite theory of democracy earlier. You’ll recall that the democratic element of his theory was the responsibility of voters to choose between different factions of the elite in general elections. The excitement of the referendum (and particularly the Yes movement) stems from the opportunity it has given citizens to experience a deeper form of democracy. To date, we have indeed been rotating government between different sections of the same political class: but during the referendum the citizenry has developed a taste for participatory democracy.

This will be the abiding glory of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. That sound you hear might not be the final cry of a dying political class, but they have certainly recognised their mortality.

Ian Gillan’s blog can be found here at Promised Joy

Reblogged this on HAPLOGROUP – bit that makes us human. and commented:

#Indyref Excellent #mustread

Thanks for this. Your reasoning for voting yes is spot on. I’ve got all my fingers and toes crossed for Thursday.

An excellent post, although the key text for understanding the September Revolution will be ‘The English Reform Bill’ (1831) by G W F Hegel. http://radicalindydg.wordpress.com/2014/02/27/the-september-revolution-and-the-ethical-idea/

Reblogged this on Bampots Utd.

I worked out that if I voted in every local, Scottish, UK and EU election between the ages of 18 and 70, I’d have put a cross on a paper 52 times. In my whole life. That doesn’t feel like democracy to me.

I want a different, more engaged and participatory democracy. So it seems do at least 2 million other people living in Scotland.

You’re right. It’s a lack of democracy that borders on the criminal, and it’s even worse for people living in England. For us, it will be about 39 crosses during the same years of our lives. Oh, how careless of us. We’ve both forgotten the AV referendum of two years ago. You know, the one that could have brought about such a radical change to the Wastemonster voting system. Even though that one wasn’t all that long ago, I honestly can’t remember whether I voted in it or not.

Vote NO and see Scotlands future….

http://www.stokesentinel.co.uk/Help-starving-kids/story-21314618-detail/story.html

Ian

Without doubt the best political article I have read for a long, long time. Not only well structured and thought provoking but easy to read.

It is not about agreeing or disagreeing with any of the theories or observations. It is the opening of a door to seek more information. That glint of light showing that we can do better by having an engaged and active community replacing the apathy and low turnouts of UK politics.

I loved it – Thank you

Thank-you so much! That’s incredibly kind of you – truly flattered.

Have a great day!

Cheers,

Ian

“The Corruption of New Labour: Britain’s Watergate?”

http://educationforum.ipbhost.com/index.php?showtopic=6382&page=1

Thank you for writing this. I found it informative and enjoyable. One of the most important challenges to emerge from the independence campaign is how to create a more independent media.