LOBO, nastier than an irate Wolf

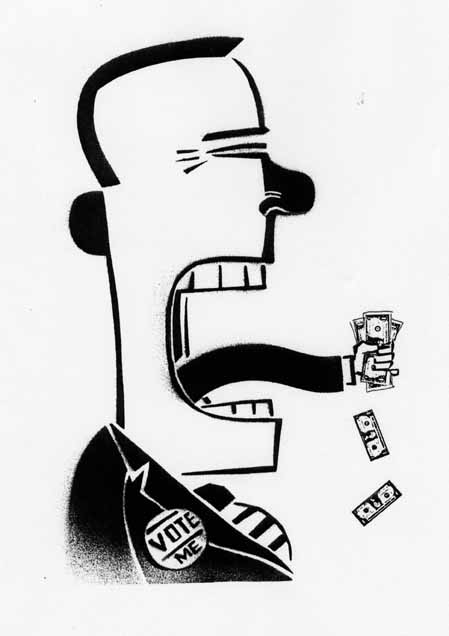

For those not in the know, Lobo is wolf in Spanish or, in English, Lender Option Borrower Option – a kind of loan offered by banks which appears designed to screw the maximum profit from councils, housing associations and other public bodies. Yes, before you ask, these are the banks that our Westminster government spent millions rescuing. So we gained a good deal there, we spent billions saving private banks in order to achieve three things;

For those not in the know, Lobo is wolf in Spanish or, in English, Lender Option Borrower Option – a kind of loan offered by banks which appears designed to screw the maximum profit from councils, housing associations and other public bodies. Yes, before you ask, these are the banks that our Westminster government spent millions rescuing. So we gained a good deal there, we spent billions saving private banks in order to achieve three things;

- we can sell the banks back to the same profiteers that brought them down at a massive loss to ourselves,

- we can refuse to exert any control over the banks (which we own) and thus ensure that the desperately needed loans to help start small businesses (or keep them alive during the recession) are not forthcoming.

- We can allow banks, via the above named LOBOs, to seriously rip off the taxpayers (who own the banks).

I look at Scandinavia and I think, nationalising banks while protecting the small investor and the general population, I think letting the banks go bust while protecting the small investor and the general population. I look at the UK and I think, buying out the banks and exerting no control whatsoever, while protecting the very wealthy investors by making the poorest in society pay the most. Gosh, am I glad I am in the UK?

Anyway, enough ranting, what is a LOBO? Some years ago I read “The Big Short” (Michael Lewis). This is a very worthwhile read; it is a highly entertaining explanation of why the banks went bust. At one point in the book he explains how financial companies created ‘insurance’ on bundles of mortgages. The insurance would then be sold to people who did not actually own the mortgages, and sometimes it would be bundled with other mortgages. The mortgages themselves would be a mixture of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ loans with nobody quite certain of the proportions. Thus the bundles included ‘good’ and ‘bad’ loans and insurance on completely unrelated loans (which may be ‘good’ or ‘bad’). Believe it or not there was actually more to it than that, the whole thing was bizarre. After a few pages of the above the author notes (in a casual aside) that the reader has probably just read the last few pages twice, only to discover they really did understand it the first time. In my case he was absolutely correct; I did understand it the first time, but refused to believe that I understood it.

Why did I go into this slightly bizarre side line? déjà vu, I read the explanation of LOBOs and, initially, refused to believe that I had understood what I had read.

Traditionally councils and other public organisations might borrow from the UK Central government at a very low rate of interest. The UK could fund that by issuing its own bonds which also cost the taxpayer a low rate of interest.

LOBOs, here goes: (this is my simplified explanation for more detail, and to understand why councils accepted these deals, see the links at the end of this short article). I will generally refer to public bodies in the section below, by which I might mean councils, housing associations or other ‘public’ organisations.

Broadly, the ‘why’ is as follows. LOBOs are initially offered at a very good interest rate. The loan is obtained via a broker; public bodies do not necessarily have a great deal of expertise in banking finance. Brokers get lots of commission on LOBOs, so LOBOs are popular with brokers. LOBOs are also complicated; understanding how a LOBO compares with another loan option requires considerable expertise. Thus public bodies may not always fully comprehend the implications of the LOBO.

A public organisation wants to borrow some more money. It already has a loan and wishes to increase its borrowing. The LOBO incorporates the old debt and increases it, though only to a limited degree. The big change is that the original loan was likely to be long term, several decades at least, with a fixed interest rate. However, the new loan (the LOBO) can be called in by the lender at regular intervals. The intervals are very short, perhaps four or five years, in comparison to the original loan. Now for the sting; when the loan can be called in the lender can increase the interest rate to a new level. Would an extra ten or thirty percent not be nice? The public body has two options; it can pay eye wateringly high interest rates, or it can repay the loan. Hang on, if four years ago the lender just increased the loan, and the original payback time was 40 years, how can they pay the sum back now, after only four or five years? The end result is that some councils are indeed paying eye-wateringly high rates of interest, though precisely how many appears rather uncertain.

I do not know how many Scottish Councils are caught up in this mess, but given the way New Labour pushed the disastrously expensive PFI deals I suspect many councils may also have been taken into horrendously expensive LOBOs.

This is something on which the Scottish Government needs to act.

- It needs to ascertain how many public organisations are subject to these loans

- It needs to provide independent expert information to public bodies seeking loans. John Swinney’s Scottish Futures Trust is presumably well placed to do this?

- In cases where public bodies are at risk of being crippled by LOBO repayments it needs to explore options to help the organisation escape the LOBO.

So far as I am aware no Scottish Council has ever defaulted on a loan, they are low risk borrowers. Does it not make more sense for the Scottish Government to determine the level of debt a public body can accumulate and then organise the loans themselves. Two possible approaches are, the government itself provide the money at a low rate of interest, or the Scottish Futures trust (or similar body) backed by government guarantee borrows the money at low rates of interest and passes on these rates to the public bodies. Whatever we do, can we work on the assumption that our banks are out to get us, it will be so much safer.

http://www.ianfraser.org/how-city-banks-and-brokers-stitched-up-local-authorities-with-lobo-loans/

http://www.dmo.gov.uk/index.aspx?page=PWLB/PWLB_Interest_Rates

http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/lobos-explained/6502500.article

http://debtresistance.uk/wolves-weymouth-councils-living-borrowed-time/

I often think that the Scottish Government should buy the Clydesdale bank. It’s owners are trying to sell and it would be an asset under government control that could be run on a non profit basis to provide sensible banking services to Scottish citizens and in due course become the currency issuer for an independent Scotland.

As is stands the Bank of Scotland and the Royal Bank of Scotland are a disgrace to their name. They are no more than brass plates that are part of multi-national thieving organisations. We have no control over them and would probably be glad to see them disappear into that den of iniquity that is the city of London

Lobo, seems plain loco.