What Lurks Behind Walls

and when the borders bleed we watch with dread the lines of ink along the map turn red. – Marya Mannes

We are creatures obsessed with walls and borders. The defining attribute of a ‘civilized’ city – until very recently – was its fortifying walls. The Great Wall of China, at a length of 3,889 miles, was the (failed) attempt of countless Chinese Imperial generations to keep out the nomadic hordes of the Asiatic steppe. The Roman emperor Hadrian built a wall along the north of Britannia to keep out the likes of Mel Gibson and his ferocious Braveheart hair. The U.S. – Mexico border is stitched together by 580 miles of steel fencing. The Israel – Palestine boundary wall is projected to span 403 miles. If there’s one thing that ‘civilized’ societies do well, it’s build walls.

On Wednesday, France announced that it will keep to its ethical and EU member-state commitment and resettle 30,000 Syrian refugees; not in spite of the attacks, but because of them…

In contemporary globalized society, this instinct to build walls has had to adapt and change form. Bricks and mortar can no longer serve the needs of a society that wishes to inoculate itself of foreign bodies. In response to the attacks in Paris on Friday, the French government announced that it would immediately ‘close its borders.’ Much confusion ensued, as there are currently no existing mechanisms with which the French government can effectively close its borders. Flights and trains continued to arrive in France with no changes in service. The Eurotunnel from Britain maintained regular operations, and passengers were not asked to produce passports. So where, exactly, have our walls and borders gone; where do they manifest themselves amongst society, and what do they look like in 2015?

Within 24 hours of the attacks, Facebook took the step of creating both a ‘safe notification’ app on its platform for friends in Paris, as well as an app that would overlay one’s profile pic with the French flag. The first app allowed users to know that their friends were ‘safe.’ The second allowed users to “show their solidarity with France with the click of a button.” As many critics have pointed out, no ‘safe friends’ app had been created two days before after the bombings in Beirut; nor did Facebook offer the Lebanese flag for one’s profile pic; likewise for the bombings in Ankara, Turkey, last month.

Can it be just a coincidence that while these outpourings of concern and solidarity for France were being reproduced thousands of times over, walls were in fact being erected in countries across the west – semi-permeable bureaucratic borders that only catch refugees in their nets, while allowing others to continue to move freely? Poland followed the attacks with a declaration that it wouldn’t take in a single refugee, through mandated by EU membership. In the U.S., twenty-five governors likewise declared that they would not accept any Syrian refugees. Canada’s newly elected Prime Minister made this Canadian proud by defying such fear-mongering and posturing, continuing course with his election promise for the airlifting of 25,000 Syrian refugees between now and the new year.

Is it too obscure to connect the Facebook apps with the selective closing of borders based on religion and ethnicity? Personally, I don’t feel so; for every act of inclusion necessitates an equal and simultaneous act of exclusion. The identification of an ‘us’ implies the identification of a ‘them’ and in this iteration the them are blatantly Non-European Muslims. Until only a few weeks ago, the former Canadian government was following a veiled policy of screening refugee applications and approving only those applications made by Christian minorities.

The instinct to put up walls and protect yourself and those you know comes naturally to fleshy organisms. The root of the word ‘belong’ literally means “to go along with.” In times of crisis the ancient Romans would carry out ‘lustration’ rituals; collective ceremonial circumnavigations of the town that included incantations to purify and protect the polis. In medieval Britain, the annual ‘beating of the bounds’ would entail a ritual communal walk about the boundaries of the village. At the same time, this peripatetic ritual was a way of taking account of those who ‘belonged’ in the village, while simultaneously excluding those who didn’t belong; namely poor vagrants who wandered alone from village to village in exile or desperation. Refugees.

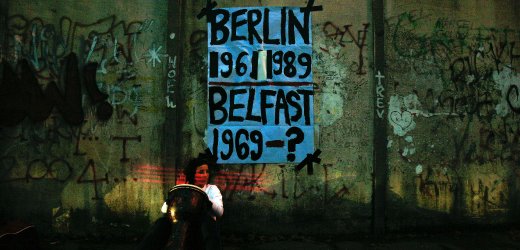

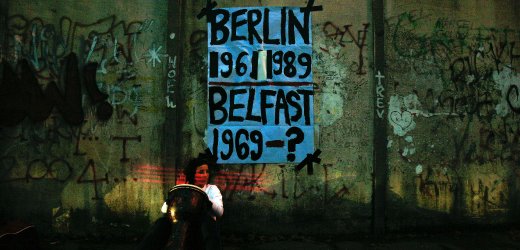

Yet history shows us another relationship between humanity and walls – the rejoicing and rapture that comes when walls are torn down. It was not only Germans who celebrated the collapse of the Berlin wall, or Americans the election of an African-American President; such collective acts of transcendence reverberate around the world, and lift the spirits of unseen millions. On Wednesday, France announced that it will keep to its ethical and EU member-state commitment and resettle 30,000 Syrian refugees; not in spite of the attacks, but because of them. Let us in our own ways, in our own communities, rejoice in similar collective acts of tearing down walls; for it is only behind walls that the unknown retains the power to invoke fear and trembling.

There are many natural borders within which communities and cultures develop over time. Then there are artificial borders imposed by power hungry elites resulting in forced integration, migration, and partition. It is the latter approach that appears to be at the root of many of today’s global conflicts.

Sane boundaries lead to sane relationships. No boundaries are a psychopath’s dream come true.

It is fear that triggers these atavistic urges to pull up the drawbridge and build more walls (whether in stone or virtual) to keep ourselves safe. We must recognise that it takes serious personal work often to overcome such unreflective responses to threatening events.

For people who claim status as political ‘leaders’, I argue that an enhanced sense of responsibility magnifies this tendency. It takes courage to take time to reflect, a moment’s reflective pause that might help overcome that initial ‘self-protective’ urge. It takes courage to come up with a more thoughtful, hope-ful and ‘heartfelt’ response, that addresses the feelings involved, but that take account of human and political complexity.

Once, moats and drawbridges stood between survival and not. Far from “atavistic” they were a practical response to real events and specific situations. But of course, the people who lived in those days did not have the privilege of a “don’t worry, be happy” approach to life. In any case, what do you propose instead?