The Dog, the Frisbee, and the Whistle

Green’s report conclusion, in summary states that:

“…. the scope of the FSA’s enforcement investigations in relation to the failure of HBOS was not reasonable. The decision-making process adopted by the FSA was materially flawed;” (A Green, ‘Report into the FSA’s enforcement actions following the failure of HBOS’: Section A. Introduction; Scope and Conclusions; para., 8, p.4)

In broad terms the failings of the FSA were also already widely understood: the FSA no longer exists. Let us therefore turn from watching Regulators pick over the bones of past failures to small tangible purpose, and address matters that may actually illuminate our understanding of the current problems of regulating banks.

You may or may not have heard of Gerd Gigerenzer, a psychologist and Director of the Centre for Human Development and Cognition, and of Risk Literacy at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin. His ideas may nevertheless have some effect on your life and mine, if only to the extent that they influence the thought or actions of senior officials at the Bank of England as the bank has wrestled with the problems of bank regulation after the Crash, or should I say the inadequacy of bank regulation; and in order to distance myself, preferably with a long cattle-prod from those people who believe the problem of regulation has already been ‘fixed’, it is clear that the tangle of inadequacy continues even now.

The clue to the Gigerenzer ideas which might be of interest to the Bank of England is most obviously found in the reference to “Risk Literacy”. Gigerenzer has had an influence not only in psychology, but economics and organisational behaviour and theory, through his advocacy of ideas drawn originally from the economist Herbert Simon (1916-2001), and particularly his concept of ‘bounded rationality’ (a term Simon probably coined) and that Gigerenzer has proselytised widely in such books as ‘Simple Heuristics that make us Smart’ (1999), ‘Adaptive Thinking’ (2000) or ‘Calculated Risks’ (2002). Compared to the conventional model of human behaviour assumed by mainstream economists (until very recently), the ‘adaptive toolbox’ of bounded rationality has much to commend it. Whether that endorsement amounts to much remains to be seen; for the conventional model of decision-making in economics with which bounded rationality must be compared was a dud.

“Modern mainstream economic theory is largely based on an unrealistic picture of human decision-making. Economic agents are portrayed as fully rational Bayesian maximizers of subjective utility. This view of economics is not based on empirical evidence, but rather on the simultaneous axiomization of utility and subjective probability.” (What is Bounded Rationality? 1999)

The existence of compelling experimental evidence for the failure of Bayesian maximisation was reinforced by the large research literature and deluge of citations that followed the influential publication of Kahneman, Slovic and Tversky, ‘Judgments Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’ (1982). Such work opened the field for Gigerenzer and other disciples of Simon’s approach, using bounded rationality, which is grounded in a critical analysis of the actual nature of human decision-making; a project that is ongoing. Bounded rationality is non-optimising, recognises the cognitive limitations of human beings using deductive logic in real decision-making situations, and emphasises the degree to which human behaviour is “automatised” (does nor require conscious deliberation in its execution), is heuristic, changing and adaptive-evolutionary. This intuitive, evidential approach to human decision-making, which will no doubt in future increasingly be driven by the discoveries and methods of cognitive neuroscience rather than economics, significantly differs from the standard economic model that in stark contrast relies on abstraction, theory, rationalism, deliberation, maximisation, and deduction; a standard model that, as a representation of reality, is deeply flawed.

What has all this to do with Central Bankers? Ask a Central Banker. Andrew Haldane, Executive Director, Financial Stability, Bank of England gave a lecture at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s economic policy symposium on 31 August, 2012 at Jackson Hole, Wyoming on the topic of “The changing policy landscape”. While Haldane’s views were not “necessarily” those of the Bank of England or the Financial Policy Committee, his views illuminate policy thinking within the Bank of England and provides us all with an insight into what ideas are being considered, and presumably the form in which they may be discussed in the City, or indeed with politicians at Westminster.

The whimsically entertaining title of Haldane’s Jackson Hole paper was “The Dog and the Frisbee”. In spite of the whimsy the paper does engagingly cut to the chase. Haldane begins by saying that “Catching a frisbee is difficult”. So difficult, you may think that you require a Ph.D in physics to catch a frisbee; but in fact all you need is a dog. The reason the dog is successful is that it keeps everything simple; the dog uses simple rules-of-thumb.

Actually the dog relies on unconscious processes working in close harmony with conscious perception. The important thing to remember here is the dog achieves this harmony of fast thought and responsive, effective action with far less difficulty than humans; but Haldane probably doesn’t want to venture onto that awkward ground, so he sidesteps it. He is a Central Banker and essentially this elaborate argument, although admirably presenting a multi-disciplinary approach to knowledge acquisition, beneath the winning display of intellectual innovation is a slightly old-fashioned, glossy but limited reconciliation of our current (newly revised) system of bank regulation, which was based on the old rational-maximisation model; thus allowing Haldane to offer a new beginning, but without, apparently undertaking fundamental structural change to the current Regulators. In Central Banking, it seems nothing is ever acknowledged to be fundamentally wrong until it has already been consigned to history and can be judged from the safety of hindsight.

Nevertheless what Haldane presents is the apparent or implicit recognition by a Central Banker of the fundamental inadequacy of the typical bank Regulators’ knowledge, methods, conceptual scheme and experience. This is quite an admission.

Haldane calls this problem the “crisis frisbee”:

“No regulator had the foresight to predict the financial crisis, although some have since exhibited supernatural powers of hindsight. So what is the secret of the watchdogs’ failure? The answer is simple. Or rather, it is complexity. For what this paper explores is why the type of complex regulation developed over recent decades might not just be costly and cumbersome but sub-optimal for crisis control. In financial regulation, less may be more.” (Haldane, ‘The Dog and the Frisbee’. 1.Introduction; p.1)

We may wonder why the regulators had such difficulty detecting disaster when the looming catastrophe in 2007 was not hard to find, if there had been the will to look at the facts (or the courage to stand out from the crowd). The Credit Crunch had been predicted long before, in an epic prophecy by Hyman Minsky (later termed “the Minsky Moment”), who died years before the Crash. Minsky was not alone. It was also predicted by Ann Pettifor. Indeed there were plenty of signals in the banking aether of an ‘accident waiting to happen’ (to put it at its kindest), floating freely in the City breeze. There is now a queue of claimants eager to join the small, distinguished cohort of prophets of the Crash, although as Haldane acknowledges, there were no Regulators among them. Hindsight is the only prediction regulators entertain.

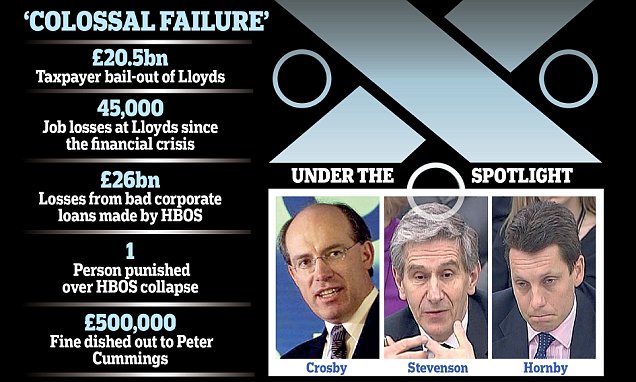

Be in no doubt the Credit Crunch was a gross failure not only of individual banks but of banking itself, including Regulators and Central Bankers. There have been few enough individual casualties of the debacle, even of reputations, among either Regulators or Central Bankers for this failure. The FSA was hastily abolished, but it was an institutional abstraction. On the other hand, the culture that produces our Central Bankers and Regulators has not materially changed; the background, education, conceptual schema, prejudices and presumptions of our Central Bankers and Regulators remain largely the same as they were before the Credit Crunch, for this is failure accumulated on an entrenched, pedagogical, generational scale. The regulatory inadequacy in prediction hence reflects a deeper issue of culture (deeper than Haldane goes).

Meanwhile Haldane proposes simplicity. He argues that modern finance is complex; and you cannot fight complexity with complexity. The old, conventional model of banking regulation is a forlorn attempt to regulate complexity with complexity. In developing an alternative simple, heuristic model Haldane refers to Gigerenzer’s ideas seven times in his paper, and uses a simple derivation of Gigerenzer’s ideas to explain this new model for Regulators, through an analogy of a frisbee and a dog. This particular analogy however, shows that Haldane is better at striking the pose of innovation than addressing the problem; from a Central Banking perspective the earliest important papers in this field to which Haldane refers, are from the 1970s. It has thus taken the Central Bankers only forty years and a major banking system collapse to recognise the problem and cautiously bring new thinking to the fore. This is not impressive.

When we examine Haldane’s supporting argument we find a case being built against regulatory complexity in the form of a root-and-branch critique of rule-focused, box-ticking regulatory exercises carried out by an ever-expanding number of regulators. Suddenly Haldane discovers and recounts a litany of current regulatory weaknesses; the lack of experience among regulators; the multiplicity and complexity of the banks’ ‘risk weights’; the emphasis on pricing risk in the financial system; the explosion in bank reporting that does nothing to reduce risk; and so it goes on. Much of Haldane’s critique is an attack on what he wryly calls “The Tower of Basel”, the large-scale, highly technical, complexity-driven, internationally agreed banking, prudential regulatory agreement known as the Basel Accord; first established in 1988 and now re-calibrated as Basel II (2004); but as a notice of its abject failings, Basel II was updated in 2010 (with even more of the same complexity) to correct weaknesses exposed by the Crash. The Basel approach allowed banks to use internal risk models as a means of “calibrating risk” which has led to complex problems of calculation, robustness, over-parameterisation (million dimension parameter sets), opacity; and a host of other very difficult problems arising from over-complexity. The Tower of Basel is Haldane’s ‘straw-man’ argument; it is a sideshow, a metaphysical discussion among Central Bankers about how many regulators and rules you can balance on a pinhead.

Haldane’s substantive prescription is summarised as follows:

“An alternative point of reference when regulating a complex system would be to simplify and streamline the control framework. Based on the evidence here, this might be achieved through a combination of five, mutually-supporting policy measures: de-layering the Basel structure; placing leverage on a stronger regulatory footing; strengthening supervisory discretion and market discipline; regulating complexity explicitly; and structurally re-configuring the financial system.” (Haldane, ‘The Dog and the Frisbee, 7. Public Policy – More or Less?’; p.14)

Haldane may consider that this prescription is “simple”, but the reference to “regulating complexity explicitly” is obscure and his subsequent efforts to develop his theme (p,14-19) do not suggest simplicity, save at recondite levels of relativity. His prescriptions are not specific or ‘concrete’ but throughout remain broad, tentative, and imprecise, even woolly; and he is perhaps over-committed to elements of the ‘status quo ante’. Nevertheless I do not challenge his grasp and understanding of the detail issues which are of course far beyond mine, or his intention in the apparently bold ambition of “structurally re-configuring the financial system”, although we need to see substance (this is where we face the prospect of sinking into an abstruse argument about ‘meanings’, or the Pyrrhic victory of form over substance): however, here I wish to challenge the proposition that his prescriptions will, alone achieve ‘simplicity’, or that he is actually applying the adaptive toolbox of bounded rationality appropriately, or with much prospect of success.

Let me return to the analogy of the dog and the frisbee. The analogous success of the enterprise is that the dog can solve a complex problem by using simple rules very rapidly and non-analytically, and catch the frisbee. This is not an analogy that stands the test of bank regulation, save in one particular. There is one dog (which we may think as the limited resource of the regulator), but in the analogous ‘real’ world there is not one frisbee: there are hundreds, maybe thousands or even millions of frisbees (banks and their multiple transactions). Worse, the frisbees (like the banks) are interconnected (contagion). There is no rule of thumb that allows the dog a chance of achieving anything worthwhile; it will simply disappear under a hail of frisbees.

Furthermore, in Haldane’s over-simplified analogy, if a dog fails to catch a frisbee there is no cost. If a regulator fails to catch a failing bank the whole system may collapse (it has the same logic as MAD – the effect of a single failure may be catastrophic). It is therefore crucial that the “simplicities” are directed at the right targets. I am not convinced that Haldane has sufficiently adapted the toolbox to the task, worthy as his aims may be. Haldane may argue that he is only offering his analogy as a rough illustration. My answer is, that it was his choice of analogy, and the strength of the analogy was its very simplicity; if he claims it is too simple he is on shaky ground; how complex does he need his simplicity to be? The dog and the frisbee is simply a bad analogy; unless it is focused precisely on what needs to be simplified most.

It is easy to criticise regulation when so much has already failed so badly, and I shall attempt not to shirk the challenge of proposing an improvement, and settle for the smug superiority of easy criticism of the proposals offered by Haldane in a complex area of public policy. My starting point is that while Regulators and Central Bankers have failed to adopt fast-action heuristics, on the other side of the ‘equation’, whether consciously or not, bounded rationality is more likely already to be widely used by banks and traders in their decision-making, for it is much more appropriate to their habitual environment and culture than for Regulators, who have acquired a deliberately contrasted and deliberative mindset. Bankers and traders therefore have an in-built advantage in speed, timing and adaptation, an advantage which the addition of regulatory complexity will merely magnify.

The answer therefore is not necessarily how we make the regulator nimbler and more flexible (at least alone), but how we use the adaptive toolbox to check the trader’s heuristic impulses, and level the field of advantage held by the banker or trader. We should oblige the trader to bring another, sharp risk factor into his/her toolbox before running the heuristics; what I have in mind is something simple but powerful, which will be drawn from declarative memory and which will, at some level at least, intrude on the trading impulse to rely on non-declarative memory processes alone. Over time such a factor may even become habitual and act as a restraining, almost intrinsic part of the trader’s non-declarative memory. What do I have in mind?

Let us keep the targets of the adaptive toolbox really simple; let us give bounded rationality at least a sporting chance. I propose a simple way to take at least some complexity out of the system altogether. My proposal is to level the field much more between regulator and trader, principally by increasing the trader’s risk in a very focused, direct and personal way. This is a test of personal as well as institutional responsibility. Let me be clear; this is not foolproof, there is nothing guaranteed in the toolbox (the price of adaptive-evolutionary failure is extinction), but I believe it is powerful, it is certainly rooted in the real world, and it is quite simple; which is of course the ‘leitmotif’ of bounded rationality. Here is a very short, simple list of proposals that would enhance the prospect of an effective application of bounded rationality, directed at the banker/trader and under which Haldane’s more esoteric, detailed, nit-picking Central Banking prescriptions may have a better chance of working:

- Bring the criminal law into the centre of the financial regulatory framework.

- Apply regulatory fines for minor offences. Apply the criminal law to major offences.

- Do not under any circumstances allow free public funds to be used to pay fines. If necessary a structured loan should be set up with a rate of interest well above the miscreant institution’s borrowing rate, with an exit for immediate repayment.

- Establish a new statutory Fraud Act that actually works in the Financial Sector.

- Use the criminal law rigorously where appropriate, and put people in jail.

- Define a Bank. Define it clearly and narrowly. Penalise transgression, but reward exemplary banking standards through the taxation system.

- Prohibit the most volatile, dangerous forms of derivative (certain CDS activities, re-hypothecation etc.) and monitor new derivative developments closely.

I do not claim that this is more than a very broad outline, nor that it is comprehensive, nor that it answers every problem; the limits of bounded rationality are that in a dynamic world boundaries move. It is a starting point only. Remember this; we have already seen in the very rare cases where the criminal law has been applied to the post-Crash scandals (scandalously few cases), that the very threat of prison, and especially of being deported to the United States to face the criminal law there, tends to have a salutary effect on the accused; in the words of Dr Johnson, an imminent hanging “concentrates the mind wonderfully”. It takes a special kind of fortitude determinedly to prioritise personal greed when the criminal law applies, and those who do still prioritise greed should expect a severe penalty, and I submit, also (8) the seizure of their assets.

Currently in Britain neither the rigour of the criminal law, nor bounded rationality (or other methodology more reliable than the failures of the past) seems yet to apply in the context of Financial Regulation, however critical bank regulation may be to the British economy or to the financial security and wellbeing of the British people. So, when now we set the half-hearted regulatory dog after the banking frisbee what do you think we are actually doing; indulging in dog-whistle politics, or perhaps more ominously, merely whistling in the dark?

Interesting, I’m not an economist but I knew this already, just not in those words.

And yes, one of the biggest regulatory mechanism missing is putting people in jail.

Another is stop access to public money.

It’s interesting that two of the great creators of the financial risk to ordinary people through deregulation were those who we would have thought had our security at heart. Democrat, Bill Clinton and Labour, Gordon Brown.

I agree that the threat of an imminent ‘hanging’ clarifies the issues immeasurably. Implicit in the threat to introduce criminal law is the question of morality. For much too long, bankers and traders (and large tax-avoiding corporations) have been allowed to ignore questions of ethical behaviour, as though this is irrelevant where money is concerned; the mantra is: we can, therefore we will.

I agree. Yes, we need effective sanctions – but that’s a kind of ‘defensive’ approach (one could say ‘negative’ – like Mosaic Law: “Thou shalt not” – as opposed to the positive ethic of service to ones fellow human beings, and the natural world).

What is really needed – in the whole of economics, not just banking – is a primary moral or ethical foundation. Economics, including finance, should serve the real needs of humanity – not the selfish interests of a few. That was perhaps the sense of the old ban on usury. Money should function like water: allowed to flow it can generate power again and again. Prevented from moving, water becomes stagnant and toxic.

The real question is how to bring morality back into business. People have been encouraged to be selfish. The positive response of many to the flood of refugees is heartening. We will learn that “love is the answer” – or continue the slide into chaos.

Interestingly, Baker, in his book “Capitalism’s Achilles Heel”, written before the crash, makes the same point about morality and ethics in business – and he’s an unapologetic believer in Capitalism.

Those familiar with the topics raised in this excellent article will be aware of the phrase “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” – Who guards the guards themselves?

Very often, all too often, we find out about scandals and failures in arrears, and very often, all too often, we are told that lessons will be learned to avoid similar situations – thus the demise of the FSA, and the birth of the FCA et al.

What if … it were the public who raised and pursued an issue, a potential scandal, involving banks, regulators and politicians? Something that has perhaps been hidden from view, and deserves to be exposed.

Let me test the water on that something – the date 25th November 2009.

On that day, the Supreme Court, issued a judgement, and a Press release to accompany their judgement, this is an extract from the Press Release:

“This appeal involved a relatively narrow issue. The Supreme Court had to decide not whether the

banks’ charges for unauthorised overdrafts were fair but whether the OFT could launch an

investigation into whether they were fair.

Lord Walker made clear that the scope of the appeal was limited – the court did not have the

task of deciding whether or not the system of charging current account customers was fair, but

whether the OFT could challenge the charges as being excessive in relation to the services

supplied in exchange (Paragraph 3). ”

The full Press Release and the judgement itself can be found here:

https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2009-0070.html

Let me ask you a very simple question – did the Supreme Court say that such charges were fair or unfair? Please re-read what was said to be very clear in your own mind what was said about fairness.

On the same day, Lord Turner (Chair of the FSA) and Hector Sants (CEO of the FSA) appeared before the Treasury Select Committee, and the chair of that Committee, on that day was John McFall MP.

Again I will keep this very simple, these are short extracts from that Committee Hearing:

Q3 Chairman: Should we just write off past bank charges and focus on the future then?

Lord Turner of Ecchinswell: “… I think that it is clearly the case that the argument about whether these charges in the past can be deemed to be unfair, which is probably the basis of most of the complaints that have been brought forward, has been definitively resolved by the Supreme Court …

Extract from here:

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmtreasy/35/9112502.htm

When Lord Turner states that whether these charges can be deemed to be unfair …. has been definitively resolved by the Supreme Court, let me ask you this very simple question – do you agree with Lord Turner or did your reading of the Supreme Court extracts lead you to a very different conclusion?

There are miillions of Bank customers affected, and £bns at stake – so your answer may prove to be important.

How do banks make money? Since Clinton, and a bit before, they have made it by gambling, making huge bets on movements in complex financial instruments, foreign exchange, sovereign debt and deception. Now, if someone wins a bet someone else loses. It’s a zero sum game, and the losers have been taxpayers.

For most of the 20th Century, banks were separated into the deposit-takers and the investment banks. The latter were the gamblers while the former were the cosy rather stuffy high street institutions who only lent you money if you didn’t really need it. Now, they’re into all sorts of clever, and dubious, activities such as derivatives and helping to hide money in tax havens.

Perhaps the first stage of any improved regulatory framework would be to return to that separation of activities.

The problem is greater than regulation. Thanks to the revolving door regulators and finance people are often the same, or at least come from the same sector of society. Gamekeepers and poachers.

Then there’s the problem of most financial activity is “socially useless” – they trade with themselves and when they’re not, as Baker, Murphy, TJN have shown, their busy enabling the syphoning off of funds from taxpayers, developing countries and parking billions in tax havens alongside the proceeds of crime, and all while western governments turn a blind eye.

There used to be a kind of social compact between society and businesses which were given a great many privileges such as limited liability in return for paying appropriate taxation and providing a few social benefits such as employment. But now that has reversed, and companies seem to think that society owes them for deigning to base themselves in their country and expect low or no taxation and being allowed to behave as they fit, following Friedman’s noxious principle that the only social responsibility of a company to make profits.

We need more than better regulation, we need a complete overhaul of the way financial and other businesses operate are taxed and held accountable.

An interesting piece but nothing has changed. The system was rotten, stil is, and no one has been put in cuffs.

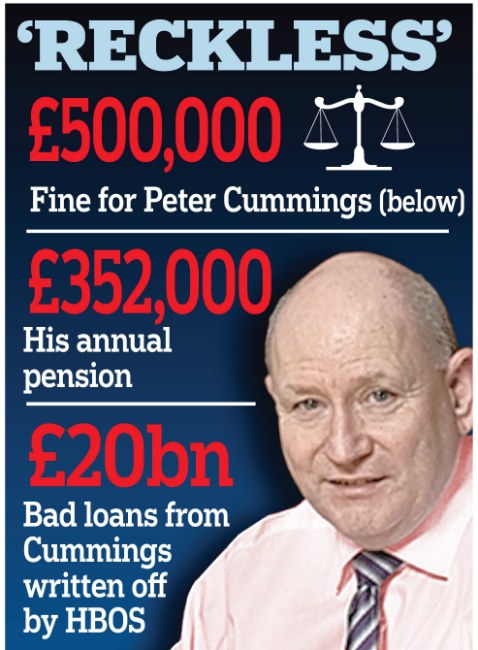

Peter Cummings, on £320,000 a year pension from his bankrupt and taxpayer bailed out employer is testimony to how continuingly rotten things are.

And now, unless I am mistaken, we are going to be plunged into war war big time as the world stage sets to explode world war three style.

That’ll keep the masses attention off the financial scandals. A good going slaughter usually does.

When indeed nothing changes, maybe we have to ask what is the source, the origin of change, or even more specifically who have the potential to be the authors of change.

Most often perhaps we see that is the role of democratically elected Governments, in the context of banking, we could extend that role to the regulators – why is it we innocently pass the individual powers that each of has to cause and create change, and why is it we naively accept a system whereby we transfer our personal ability to be an author of change to others, and all too frequently we find that they have failed us.

And yet, consider what will produce the origin of Scottish independence, who will eventually be the sole authors of that independence – it will not be Governments, nor regulators, if anything, and we know this, they will act as the barriers to the change that many wish.

We should learn from the failings of others, recognise the barriers that they may erect, but most importantly we should recognise that perhaps there are none more foolish than we ourselves when it is we who grant them the powers, when it is well within our personal powers to be the authors of change.

That concept lies in the post I made above, to find areas where it is possible to identify and evidence the failures of Governments and Regulators, and instead of complaining, or listing remedies, and then asking those who have already failed to sort matters out, I am suggesting we as individuals are in no way powerless to take on the task, and become the authors of the change. I hope early next year to develop what lies behind my earlier post.

If that concept of self generated change is demonstrably true as it relates to Independence, and it will only occur because individuals pick up the pen and write their future, then why is it any less true in other areas?

When we concede and seemingly accept that nothing has changed, maybe instead of pillorying others, we need to look in the mirror to discover who may really be responsible?

There is a good point here. The changes we have seen in the politics of Scotland have not been effected by political parties, save indirectly; they have been effected by the Scottish people over the Referendum campaign, the General Election and by a change in culture in Scotland over the last two years (a change that cannot easily be quantified, precisely identified, or explained away); I think the SNP are the only political party that understands this, and the SNP knows that it is merely ‘riding the wave’. What this tells us us is that this is not a “result”; there is no result, but a process. It is ongoing; it is for ordinary people to remain active, interested and committed, however hard, irrelevant (or pointless) that may seem. Ordinary people, active in their communities, campaigning, writing, debating, asking awkward questions, making demands, are more effective than, perhaps, they know.