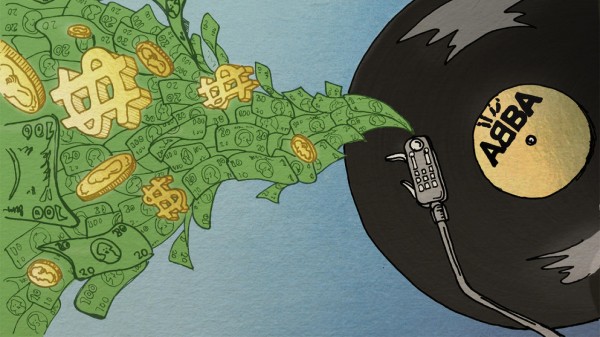

Money, Money, Money

Must be funny, sang Abba – and it is, as we’ll see later.

Must be funny, sang Abba – and it is, as we’ll see later.

First, here’s a question: do you trust me?

You do a bit. At the very least you have started to read this article. So you must hold a modicum of trust that reading it will bring you something of value – a little entertainment, new information, perhaps some satisfaction by the time you reach the end. To continue, your trust must grow. Of course, there comes a point where a reader must feel confidence in a writer’s skills. They must feel secure in the writer’s hands – not just that there won’t be obvious grammatical mistakes the writer should have avoided – but that the journey they are being taken on is coherent, is well-planned, and will eventually be worthwhile.

That point is around now. It’s my job to demonstrate to you that I know what I’m about. I have to show that I have something valuable to say and that I can deliver it to you on this page. You also need to feel I won’t tax you over much but nevertheless there will be meat on the menu.

And that is all perfectly reasonable. We normally don’t trust new acquaintances until we get to know them. Trust is built up; it isn’t just taken for granted. I expect to have to win you over.

Yet with money, where far more trust is needed than merely to be persuaded to read a couple of thousand words, it is almost taken for granted. We treat day-to-day sums with barely a second thought. Banknotes are accepted in shops from total strangers. We hand them over to unknown retail assistants, accept them as change, or take them from the cash dispenser fully confident that the value printed on the face of the paper is what it says it is. That simple inner decision – while not even considering the possibility of forgery – is a massive act of trust. We believe that this rectangle of paper with just that texture and those colours printed on it carries a value hundreds of times greater than the material value of the note itself. That belief triggers a whole series of conscious and unconscious psychological states. Don’t we all feel a sense of contentment when we take a wad of notes from the hole in the wall? Who doesn’t enjoy the soft papery scent of freshly printed notes as we slip them into our wallet or purse? And when you pay for a round at the bar doesn’t it feel good, don’t you feel so confident when you hand over a twenty pound note even if a tenner would suffice? These are the feelings we all notice. There are subconscious effects too. Psychologists have discovered that merely handling money, even money belonging to other people, makes us less sensitive to criticism. It also, surprisingly, makes us less generous.

Yet with money, where far more trust is needed than merely to be persuaded to read a couple of thousand words, it is almost taken for granted. We treat day-to-day sums with barely a second thought. Banknotes are accepted in shops from total strangers. We hand them over to unknown retail assistants, accept them as change, or take them from the cash dispenser fully confident that the value printed on the face of the paper is what it says it is. That simple inner decision – while not even considering the possibility of forgery – is a massive act of trust. We believe that this rectangle of paper with just that texture and those colours printed on it carries a value hundreds of times greater than the material value of the note itself. That belief triggers a whole series of conscious and unconscious psychological states. Don’t we all feel a sense of contentment when we take a wad of notes from the hole in the wall? Who doesn’t enjoy the soft papery scent of freshly printed notes as we slip them into our wallet or purse? And when you pay for a round at the bar doesn’t it feel good, don’t you feel so confident when you hand over a twenty pound note even if a tenner would suffice? These are the feelings we all notice. There are subconscious effects too. Psychologists have discovered that merely handling money, even money belonging to other people, makes us less sensitive to criticism. It also, surprisingly, makes us less generous.

Perhaps these feelings are part of what makes my blood boils when I hear the stories of Scottish banknotes being refused down South. You may remember during the Rugby World Cup that the Edinburgh Evening News carried the story of a Rugby fan whose Scottish banknotes were refused when he tried to buy merchandise in a World Cup outlet. Only yesterday (24th November) I read in a Facebook feed one Scot’s response when his £20 Scottish banknote was turned down in a well known coffee franchise in London: “So, what would you do if [insert name of well-known coffee franchise] in Canary Wharf refused to take a Scottish £20?? I’ll tell you what I did, I said no problem, got my bank card out ordered 4 tall skinny caramel lattes, 4 cheese & ham toasties, 4 Belgium brownies and a hazelnut frappe, asked if I could see them to make sure I’d ordered the right thing, when they got it all ready I refused to pay and walked out, get that RIGHT UP you. Girls face was priceless!! Guy behind me was in tears!!”

I make no claims regarding the veracity of the story – I didn’t recognise the poster’s name and I’ll remain silent on the name of the coffee franchise – but the sentiments expressed in that story and in similar anecdotes in the comments which followed show the quite natural indignation when an item we regard as valuable, and hold as dear, is rubbished.

I make no claims regarding the veracity of the story – I didn’t recognise the poster’s name and I’ll remain silent on the name of the coffee franchise – but the sentiments expressed in that story and in similar anecdotes in the comments which followed show the quite natural indignation when an item we regard as valuable, and hold as dear, is rubbished.

I’m tempted to say that refusals like this break the trust which underpins the whole monetary system in the country. If Bank of England notes were regularly rejected in any substantial number by people in the largest country in the Union, then the UK pound would take one step towards collapse. In real terms, though, the proportion of Scottish banknote refusals compared with the number of the notes which are accepted daily in Scotland must be tiny. What is really going on in these anecdotes is racial discrimination. There is, in fact, no legal requirement for any trader to accept a customer’s offer to trade, but if the refusal is on the grounds of nationality then it could be illegal. The question would be whether refusal on the grounds of the country of issue rather than the customer’s nationality is actually racial discrimination. In the case of the retailer who issued a blanket ban on Scottish notes it’s hard to think of a motivation which isn’t racial. In other cases it may be no more than lack of familiarity with our banknotes and a concern about forgery.

While it’s gratifying to read stories like the one about the coffee franchise – well, it is to me – I doubt they have much effect on attitudes south of the border. Scottish banknotes are legal currency, approved by the UK government, and backed by an equal deposit in the Bank of England. But that fact is either unknown or deliberately ignored. What they are not is legal tender, not even in Scotland. Legal tender has a very specific meaning in relation to settlement of debt. A debt can be paid off by any means the debtor agrees to accept. With legal tender it’s a different matter. Let’s take the example of going for a meal in a swanky restaurant. You don’t pay until you leave, so you are effectively in debt once you’ve swallowed your entrée. Suppose you offer to pay with Scottish notes. The restaurateur refuses but then notices your blingy wristwatch and says they’ll accept that as payment instead. But you like your wristwatch and you know it cost twice the price of the meal. If you now go into your other pocket, pull out Bank of England notes, the restaurateur has no option but to accept them as payment, because BoE notes are legal tender in England. However, in Scotland BoE notes are not legal tender at all and it would be tempting to encourage our Scottish restaurateurs to refuse them on that ground. It might be rather satisfying if they did. But I imagine that most of them couldn’t be bothered with the hassle when push came to shove. They’d just take the money.

While it’s gratifying to read stories like the one about the coffee franchise – well, it is to me – I doubt they have much effect on attitudes south of the border. Scottish banknotes are legal currency, approved by the UK government, and backed by an equal deposit in the Bank of England. But that fact is either unknown or deliberately ignored. What they are not is legal tender, not even in Scotland. Legal tender has a very specific meaning in relation to settlement of debt. A debt can be paid off by any means the debtor agrees to accept. With legal tender it’s a different matter. Let’s take the example of going for a meal in a swanky restaurant. You don’t pay until you leave, so you are effectively in debt once you’ve swallowed your entrée. Suppose you offer to pay with Scottish notes. The restaurateur refuses but then notices your blingy wristwatch and says they’ll accept that as payment instead. But you like your wristwatch and you know it cost twice the price of the meal. If you now go into your other pocket, pull out Bank of England notes, the restaurateur has no option but to accept them as payment, because BoE notes are legal tender in England. However, in Scotland BoE notes are not legal tender at all and it would be tempting to encourage our Scottish restaurateurs to refuse them on that ground. It might be rather satisfying if they did. But I imagine that most of them couldn’t be bothered with the hassle when push came to shove. They’d just take the money.

Money, however, is more than banknotes, coins, and legal tender. This is where ABBA were right – if they actually knew what they were singing about. Only 3% of the money supply in the UK exists as paper notes. The rest is created by the banks in the form of interest-bearing loans to companies and individuals. Contrary to what most people think, banks do not hold reserves from which they hand out their loans. Instead they simply increase the balance in the borrower’s account. They look for reserves later. The money exists as no more than the state of a memory location in the Bank’s computer. This is the Fractional Reserve Banking System. In the US banks must hold at least 3% of the total money they lend – which to me seems an astonishingly small amount – while in the UK there is NO legal reserve requirement. UK banks can create as much money as they want.

Here we really see where trust has to come in. The banks must trust that we will pay back our loans and those who have savings trust that there won’t be a run on the banks! If you consider that 97% of the money in the economy exists in this form of debt, then it’s easy to see how fragile the monetary system is. If trust in the pound disappeared, i.e. trust in the ability of the government to support it, the UK pound would collapse in an instant. Yet it’s this ephemerality, this vapidness of money which Scotland could lever to its advantage. What value does such an insubstantial concept carry? What, in fact, is value anyway?

Both Adam Smith and Karl Marx used a labour theory of value in their attempts to crystallise the concept in some concrete way. Marx defined the value of a commodity in terms of the work required to make it. While this makes sense it doesn’t take human psychology into account. Smith defined value as the work someone is prepared to undertake in order to acquire a commodity. This, at least implicitly, includes the notion of desirability, a much more impermanent entity which is both personal and changeable (I still can’t make up my mind about 2016’s summer collection). Nevertheless, wherever wealth accumulates, objects of inherently intrinsic value and those with some perceived desirability can be seen.

But people in Scotland work damned hard too. Shouldn’t our economy be as strong as Germany’s? Well, it should be and there is a way, without waiting for the full benefits of independence, it could go a long way to getting there.

John Ruskin claimed “There is no wealth but life”. In his view wealth included love, joy and admiration. The richest country was the one with the largest number of ‘noble and happy human beings’. I can’t disagree. Life without art, without music, without the company of family and friends, without recreation, without security of income and without peace, is a life diminished. It is poorer in Ruskin’s terms. Where ‘wealth’ means ‘material wealth’, in the stricter context of everyday usage, I think a better aphorism is “There is no wealth but work”. Within any economy, nothing carrying a value which can be measured using money, including its apparent desirability, gets there by itself. Somebody has to do some work even if it is no more than taking it to the marketplace. Those things which we think of as provided by Nature – raw materials and agriculture – need human intervention before they become useful in an economy. Oilfields must be drilled, diamonds must be mined. Crops must be sowed, protected and harvested. They must be packaged, transported and distributed before the customer can pick them off the supermarket shelf where a stacker’s work has placed them earlier in the day. Those wealthy people who get their money to ‘work for them’ indulge in a delusion. Money cannot work. It is impotent. Every penny of the dividend shareholders receive is earned by the work done by the employees of the company they have shares in. All the interest you accrue on your savings account is gleaned from the hard-earned additional money paid by borrowers as the interest owed on their loans. A country is made wealthy by the work done by its citizens. If there is any reason why Germany has such a strong economy, it’s because her citizens work damned hard.

But people in Scotland work damned hard too. Shouldn’t our economy be as strong as Germany’s? Well, it should be and there is a way, without waiting for the full benefits of independence, it could go a long way to getting there.

I support the proposal of the New Economics Foundation (NEF) to create a Digital Currency for Scotland. At a cost of around £3 million to set up the infrastructure, the Scottish Government could launch the ScotPound (S£) as complementary currency existing in parallel with the UK pound. Transactions would be cost-free, unlike debit or credit cards payments. Mobile phones would be the main instrument of payment. The new currency would be used only within the territory of Scotland and could never be removed from it. Thus any value generated by its use would remain here. At the time of launch every citizen on the voters’ roll would be credited with S£250. This would add nothing to the UK deficit as the currency would rapidly acquire a value of its own shortly after its launch.

I support the proposal of the New Economics Foundation (NEF) to create a Digital Currency for Scotland. At a cost of around £3 million to set up the infrastructure, the Scottish Government could launch the ScotPound (S£) as complementary currency existing in parallel with the UK pound.

Here’s how that would happen. After you sign up (a legal agreement to honour any debts you may incur), you receive S£250 in your account. Suppose you decide to try it out straight away and go to the local butcher to buy some meat for dinner. As soon as you have paid and left the shop with, say, S£10 worth of prime beef the currency has acquired value in your mind. The butcher, however, is in the red. What they have to do is to use the ScotPounds they will receive by the end of the day to buy more sides of beef from the local farmer. As soon as the order is delivered the new currency will have acquired value in the butcher’s mind. Next, the farmer has to use the ScotPounds the butcher handed over either to buy grain from their neighbour’s farm or, more crucially – since this is what adds most of the value – to pay part of their workers’ wages in ScotPounds. The workers have already spent their S£250, know that they work, and are delighted to earn some more to use again. These workers, and any others who receive some of their salary in ScotPounds, buy their groceries in the new currency, and the cycle is complete. The value of the currency now exists in the minds of the people who use it. They trust it because of the goods or services they have purchased with it and they are willing to work to acquire it.

An important aspect of the proposed ScotPound would be the application of ‘demurrage’. Demurrage is used in the local currency of Bavaria, the Chimgauer, and is a small tax applied if the currency is hoarded. The purpose of the charge is to encourage people to spend their money and increase the ‘velocity of circulation’ in the economy. The astonishing success of the Austrian Wörgl experiment of 1932 in dramatically reducing unemployment during the Great Depression was credited to the use of demurrage – until the central bank put a stop to it!

All this may sound utopian and fantastical, but other countries are already successfully operating complementary currencies in many forms, some having been around for a long time. The WIR Franc in Switzerland was founded in 1934, eighty one years ago.

If the Scottish Government had the courage to take up the idea it would stimulate the economy of Scotland and tackle unemployment at its source. Perhaps it can’t be done in one step, but it could be trialed in a town or city – Dundee comes to mind – and then rolled out across the country.

What better way would there be to answer the pettiness of those retailers in England who refuse Scottish banknotes? We don’t return the pettiness – satisfying as that may be – but we create a currency unique to Scotland which by its structure gets people working and spending and makes our economy the envy of the rest of the UK.

Yet for me the most important gain would be psychological. It would allow ordinary Scots, through direct experience, to see the currency question, the Achilles Heel of the Yes argument in IndyRef1, for what it really was – a non-issue.

That’s an awful lot of words to make a point, which, incidentally and sadly, got rather lost along the way.

I agree with James Alexander’s comment but it is good to encourage this discussion for reasons outside the Independence debate.

One important issue to be addressed isthat all forms of electronic currency may be used for surveillance and, potentially, oppression. Recent actions and legislation suggest this to be the current default tendency (such as actions against Wikileaks post Snowden).

But an e-currency with privacy built-in would offer a counter argument in its place. Something any ‘progressive’ government should look at.

An idea worth pursuing. Crypto currency whether it be BitCoin or any other, has long been touted by the likes of Max Keiser on RT as a means of escaping the power of the “Banksters”.

Crypto currency stored in an individual on line “wallet” has the advantage of being 100% peer to peer with zero chance of a Bank skimming a fee. The Banks in fact detest Bitcoin and see it as a mortal threat. It is on line but with an ironclad and impenetrable security protocol.

But acceptance is the key. Work needs done on creating an on line infrastructure. But with the likely stock market and housing bubble collapse coming in 2016, things could change quickly. In the event of this banking collapse, bailouts are not going to happen again, Cameron has made that clear because the debt would be unbearable for Westminster. So how do banks cover their losses? Bail ins – Cyprus style. Deposit accounts will be raided. They already are because of low interest rates. These will go negative in a bust, as they already are in some parts of Europe, ( Sweden, Switzerland) where people have to pay the banks to keep cash there.

Then people will be come very, very interested in Digital currency.

The equivalence of work to money has its limitations. What would happen to people who cannot work to earn their S£, like the disabled? We have a moral and social duty to them. The thing I like about it, though, is that it would give true value to a measured amount of work, and the City currency traders who take their cut and who make a mockery of reward for an honest days’ toil wouldn’t be able to make money simply by gambling. Playing the stock exchange and money markets using real money makes a mockery of real work and changes real cash into virtual cash. Unfortunately they can still buy their Porsches with this funny money.

No one in the City has a notion about adding value to a product or raw materials.

The rest of us do the work they are unable to do. i.e. we care for them.

So Scottish money is a pish take as well. Another reality i’m not that surprised to discover. I was presented with a board once in an International airport with all the pish take currencies on it, and there they were, the Scottish bank notes, holding about three or four positions alongside the Bangladeshi Taka and the Icelandic Krona (just after it crashed).

Off topic but I read/heard somewhere that Finland was giving £800/month to it,s inhabitants adult I suppose,don,t know the ins and outs but interesting.What if we were to give a similar amount to our citizens how would this pan out?from this amount national health stamp and all other relevant deductions were made,the rest would still circulate throughout the communities perhaps creating or supporting work,if the government can “magic up trillions to give to the robber barons why cant we do the same for the rest of the population,the argument used against the likes of this solution is that it isn,t earned through production doesn,t wash as the fiunancial district in the city of London produce nothing but lies.

It seems to me that Fractional Reserve Banking is a different matter from the ability of commercial banks to create new money, yet you seem to run these together.

To see this imagine all money really was just cash, that is notes or coins, issued by the Central Bank. (Even before digital banking that wasn’t the case, money was ink on ledgers rather than voltage differences in computer memories and that saved truckloads of cash being transferred between banks each night as they settled accounts. But just imagine that for the sake of making the point).

In that case commercial banks couldn’t create money/cash, only the Central Bank’s printing pressed and mint could. But private banks could still engage in Fractional Reserve Banking. Suppose you get £50K redundancy money and put it in an instant access account in bank A. If your employer was in bank B and that’s the only transaction between A and B that day, a van takes £50K in notes from bank B to bank A. If there is a 10% fractional reserve system, bank A can lend £45K out the next morning in a mortgage or other long-term loan which it can’t call in even if you come in the day after and demand your £50K back out (thus the danger of fractional reserve systems, of course, that of bank runs, but to eliminate, rather than just reduce by reserve requirements, the possibility may well have costs too high to pay, in terms of growth for example). So fractional reserve but no private money creation are different things.

I agree commercial banks can create new money: the Bank of England (when are the SNP going to demand it changes its name and notes to Bank of UK?!) itself says so. The old textbook idea that high-powered central bank reserves have to be held seems to be a fiction of the textbooks, at least in the UK. And I agree that idea of a digital currency is a very interesting one (as is the idea of a citizen’s income or something similar, e.g. job seeker’s allowance paid to everyone with compensating tax rises, as a way of avoiding poverty traps). But it seems to me these ideas are distinct, independent and need to be clearly distinguished.

The digital currency one seems to most important for the independence debate. I don’t mean ‘Bitcoin’ or any such, nor a currency with no Fractional Reserve requirements but rather a currency used solely in online transactions, as the Euro was for the first three years of its existence. The Scottish Govt’s fiscal commission had a dual currency as one of its options but said very little about it. I’d like to see the government put more economists on to this one and investigate the possibility and utility of running, prior to independence, dual currencies, with sterling still the ‘cash’ currency on the street, as a way of defusing some of the currency worries Project Fear capitalised on.

To be clear, FRB doesn’t exist in the uk now. When a loan is drawn up a new account is created with a new asset and liability.

Banks settle their accounts to one another (net settlement) using central bank reserves. If they are short at the end of the day they borrow on the inter bank market or as a last resort from the central bank (which will always provide reserves). So lending isn’t reserve dependent on any way.

The issue of cash is separate. A bank will keep a certain amount of cash as people will obviously want to draw from their demand deposits at certain times in the form of notes. The less cash the better for the bank as there are cost implications. This is why there is a limit on daily cash withdrawals.

There is simply no relationship between the quantity of cash in the safe and bank lending.

As for complimentary currencies in Scotland, we are way behind ruk and the rest of the world. We need a polyculture of regional non debt based currencies. If nothing else it will demonstrate to people that the idea of money having to be lent into existence at personal cost is nuts.

The flat earth economics of Osborne actually means that it is up to the private sector to increase the money supply which means an increase in private debt. The private sector however is already leveraged to the hilt and it’s reluctance to take on more debt is ruining the tory plan.

@scottieDog ‘To be clear, FRB doesn’t exist in the uk now.’. Well banks still borrow ‘short’ from depositors and lend long. If all the instant demand depositors of a bank, ‘Northern Rock’, as it may be, demand their deposits back at the same time, the bank will not be able to do so, even if its assets, in the form of its loan book, add up to the total required. That’s fractional reserves. A central bank could get round this by ‘fiat’, by simply printing the money, or rather creating it on its computer systems. But the ability of private banks to create new money does not extend that far.

That’s different from setting down a legal ratio of Central Bank reserves to total liquid liabilities of private banks. Having that, or reintroducing that, would in effect, prevent private banks expanding the money supply beyond the rate the Central Bank determines just as my thought experiment of a purely cash economy would. But it would still be possible to borrow short and lend long, to hold only a fraction of one’s assets in fully liquid form and so not be able to meet a demand for deposits by all the instant demand depositors. Or conversely, one could, whilst still maintaining legal ratios of Central Bank money to liabilities, ban fractional reserves in the form of borrowing short and lending long. That is, require banks to hold liquid assets to the same amount and time duration as their demand depositor liabilities. But that would surely be a very idea, crippling the dynamism of the economy

I’m not sure that these issues are very relevant to Scottish independence. The issue of currency, and in particular a possible dual currency, one purely online, the other sterling, is. I’d like the government’s economic experts to tell us more about that. Is it legally possible for Scotland, prior to independence, to run its own online currency, after the fashion of the Euro in its initial years? Is it financially practical? Would it enable the Scottish government to acquire sterling reserves and eventually float the currency? Would it resolve the ‘asymmetric shock’ problem (though the level of oil prices has, temporarily anyway, resolved that for now)? Most importantly perhaps, would it, after a few years, provide the psychological reassurance those No voters tempted but who were too scared to vote for independence need?

Fiddling about with the currency is not going to solve Scotland’s fundamental problem, which is primarily that we do not produce enough export trade, and what trade we have left (after 30+ years of successive UK Governments scorched earth de-industrialisation, de-regulation and privatisation policies) is today owned offshore with the ‘value’ siphoned out of the economy (e.g. whisky, oil/gas, energy/transport ‘utilities’, land estates etc), whilst at the same time we have had ever rising imports of manufactured/retail goods. To solve this Scotland would require major reforms and in particular far better regulation of major industries and assets, combined with a focus on trade facilitation. Otherwise we are heading for continued decline, irespective of whether we use the pound or Kevin Bridge’s smakeroonie.

There is a simple reason China has been swimming in the rest of the world’s cash: trade.

Nice well-written article making the excellent point given in the last paragraph – “to see the currency question, the Achilles Heel of the Yes argument in IndyRef1, for what it really was – a non-issue”.

What made it a very real issue was that the truth about money is still quite difficult to understand for most people, because there’s a hell of a lot of rubbish talked about it. Sometimes it’s quite deliberate to confuse the punters, such as from George Osborne who wants you to believe the government of the United Kingdom hasn’t got any of it (at least not for the things that you want to spend it on), but mostly from ignorance that is parroted by the media.

Money is not a commodity that is in limited supply. As the writer notes, nowadays money is created by governments and banks at essentially zero cost as it is simply magnetic patterns on hard discs. No unpleasant digging of scarce metals out of the ground is required. You don’t even have to get dirty fingers from printer’s ink.

So essentially the creation of money is not a problem, the bank doesn’t need thrifty savers to

‘lend’ you half a million quid for your one-bedroom flat in London, it just creates it on the spot by

tapping the keyboard and then charges you as much interest as the market will bear.

It should be obvious that government ‘borrowing’ is an empty farce as well, because where did

the private sector money that bought the government bonds come from? It was created out of thin air either by the government itself in the past, or by the private sector banks whose money creation powers are backed by…the government. Government ‘borrowing’ is simply a mechanism to reduce the money creation abilities of the government. However no such direct control exists on private money creation by banks, hence the boom and bust cycles of the economy.

What about the private sector, the engine of Osborne’s dream economy? Doesn’t it make any money?

It would like you to think that it does, but obviously no private sector company (including Amazon and Apple) actually makes money. That would be illegal. They just shift existing money around, usually from poorer people to richer people.

At the end of the day money is a social construct backed by the future productivity of the population.

It’s value and function are what people believe it to be. However it’s apparent value and function are controlled by the rich, for the rich, assisted by their very efficient propaganda machine.

The machine is currently telling you that the country is nearly bust, so you need austerity. Apparently we can’t now afford the social services we created after the second world war when we really were bust.

The relevance to the Independence movement is that if you have no faith in the future productivity and creativity of the Scottish people you will have no faith in its currency either. The creation of a

parallel Scottish currency and its everyday use would help to reduce the quite natural fear of change, however I would expect real resistance to its creation from the existing unionist financial power structure (i.e. all UK banks including the BOE) for that very reason.

This discussion is great. We need to develop thinking in Scotland about how we might use money differently, whether this is the potential to create new banks in Scotland (perhaps in combination with bringing the Scottish bits of RBS/HBOS under more democratic control) or trying to develop a new digital currency.

I think the Scotpound report should be promoted as probably the initiative so far on this – anyone know of anything else? http://www.neweconomics.org/blog/entry/scotpound-a-new-digital-currency-for-scotland I agree with many of the commentators that its primary importance as a proposal is to get people to think about and understanding money. So, even if it only ever formed a small part of total currency in circulation and never became an alternative to the UK pound it would still help people think and would be a way of testing how a new currency might work. What Hugh did not explain was why people might use the Scotpound and in my view the brilliant part of the proposal – which is probably why the UK Government would try and stop it – is that the Scotpound could be used to pay tax. The key factor behind all fiat money is it can be used to pay tax – its acceptance by the state is what makes it a universal currency. Conversely if you cannot pay tax, as with local currencies, they are very hard to get off the ground. Its what could persuade people to accept Scotpound as part of their salary or benefits…….. The second really important potential of scotpound is that with the UK govt still committed to austerity, it could allow the Scottish Govt, once the currency got established, to start issuing more Scotpounds to counter the effects of cuts at Westminster. The Scotpound report suggested everyone would get the same amount initially and I think this would be necessary to give everyone a stake in the new currency; but after that, extra injections of Scotpound in the economy, could be from the bottom up, ie via people on benefits. If the Scottish Government started to work on developing the currency now it could just about use it to counter some of the cuts that will accompany the introduction of Universal Credit.

On the banking side, if we had a Scottish bank – or linked community banks – that could create money as debt, we could fund a whole series of capital projects (which would create work) where there was a revenue stream that could repay the debt over time – from cross rail to new housing to solar panels on houses – without this being constrained by Westminster limits on state borrowing and at cheaper rates than those offered by our current banks.

Is there any appetite out there for an alternative Scottish money group to start working up and publicising proposals………..along lines that NEF has been doing (and with links to them) but looking at what the Scottish Parliament could do/sponsor?

http://www.capercailliebooks.co.uk/shop/playscripts/little-red-hen-by-john-mcgrath/

The article takes a very long way round to say that money is a social lubricant in terms of exchange of goods or services but has no value of itself.

All money is debt – a promise to repay in one form or another. If we don’t trust the debtor the money/promise is ‘worth’less.

Our problem is that we now live in society where many think (mostly those who have little) that money does have intrinsic value and that people who deal in money are more important/worth more than those who produce our food, run our power stations etc

Billionaires ken fine that money has no value of itself and depends entirely on trust – therefore most of their ‘wealth’ will be held as land, commodities, property etc and even their liquid cash may be spread around several currencies.

I dig the ground (really) and plant tatties (ridiculous, I know). Later on I dig up the crop and feed myself over the winter. This will not appear in the all important GDP. Worthless or what?