Land Rights Now

The Scottish Government has an action plan to double lands in community ownership in Scotland to 1 million acres by 2020. Coincidentally, the Global Call to Action on Indigenous and Community Land Rights will be launched in 2016 with a target to double the global area of land legally recognized as owned or controlled by indigenous peoples and local communities by 2020.

The growth of community land ownership in Scotland over the last 20 years has led, in communities now owning their lands, to a reversal in declining population numbers, a greater sense of control and security leading to more long-term thinking and planning, a deepening sense of identity and belonging, financial stability, increased investments, and job creation. Community land ownership can be challenging and takes time, but overall the experience in Scotland shows that it leads to material and psychological benefits and increased community resilience.

The benefits of communal land rights are increasingly being understood around the world. A fast growing body of research, much of it focused on Africa, Latin America and Asia, is demonstrating that communities with secure land rights manage their lands and natural resources more effectively and sustainably than any other management or ownership regime.

Secure community rights result in reduced deforestation, leading to lower global CO2e emissions. For instance, in the Brazilian Amazon, it was found that rates of deforestation were 11 times lower within community owned lands than in other areas. Studies in over a dozen countries have reached similar conclusions. 13-20% of global CO2e emissions are from deforestation and forest degradation. This level would be far greater if indigenous peoples were not protecting 168 billion tonnes of carbon on their territories.

In Scotland today 432 land owners still own 50% of private land, the result of the takeover of community lands over centuries by powerful private interests. This situation is now slowly starting to be addressed: through the 2020 1 million acre target; in the Community Empowerment Act; and in the Land Reform Bill currently passing through the Scottish Parliament. The call by a growing and vocal movement for a more radical Land Reform Bill underlines how important the issue has become in Scotland.

Yet in spite of the benefits of community tenure, such aspirations face fierce opposition from those sectors of Scottish society that do very well out of the current pattern of land distribution, one described by Professor Jim Hunter as “the most concentrated, most inequitable, most unreformed and most undemocratic land ownership system in the entire developed world”.

“the most concentrated, most inequitable, most unreformed and most undemocratic land ownership system in the entire developed world”.

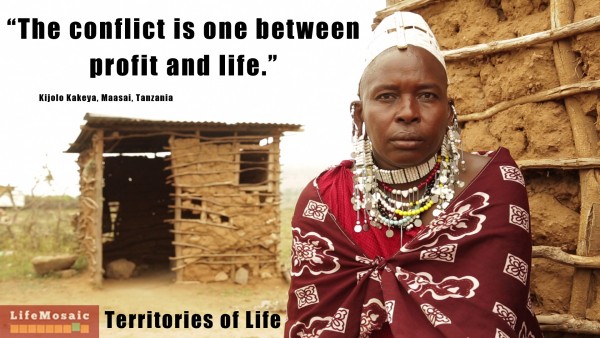

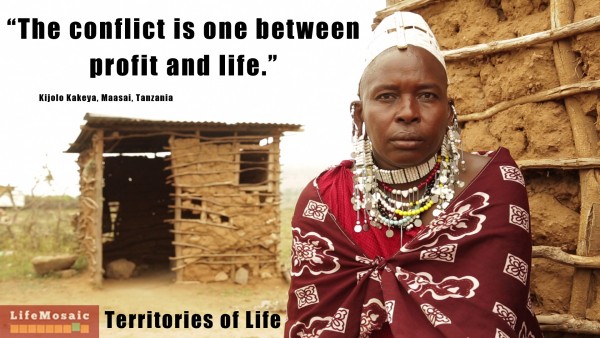

In the ‘Majority World’, there is a growing clash between elites grabbing the commons and communities defending them. Rising global demand for resources leads to aggressive expansion of extractive and agro-industries on community lands. These land grabs result in indigenous communities being displaced from their territories, their livelihoods squeezed, their basic rights denied, and the ecosystems on which they depend destroyed. 116 murders of environmental defenders were recorded in 2014 (the number of unrecorded deaths is likely to run much higher), and 40% of those killed were indigenous people. As Kijolo Kakeya, leader of a Maasai women’s movement in Tanzania says: “The conflict is one between profit and life.”

By continuing to foster diverse human ways of being on the planet, deeply rooted knowledge and collective memory, securing community land rights helps to protect and nurture the resilience of human communities. As the late anthropologist Darrell Posey showed through his work with the Kayapó of the Brazilian Amazon, “the best way to conserve the diversity of cultures and nature is through the empowerment of the people and peoples whose local knowledges and experiences form the foundations that conserve much of the earth’s remaining biological and ecological diversity.”

One contribution to this urgent task is the Territories of Life toolkit, a series of 10 short videos for empowerment that share stories of resistance, resilience and hope with communities on the frontline of the global land grab. The toolkit brings critical information to indigenous communities, to help spark community discussions, planning for the future and movement-building in their defence of their rights, territories and cultures. The video toolkit has a primary audience of indigenous communities across Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia. At the same time, creative solutions to collective problems forged by the likes of the Misak people in Colombia, with their long-term, community-led plan for self-determined development, can inspire our own debates and our struggle to reclaim our futures here in Scotland.

Support LifeMosiac’s Crowdfunder here.

“a greater sense of control and security leading to more long-term thinking and planning, a deepening sense of identity and belonging,” is this what the Tory government might say about owning your own house……………so this can’t be too far away from their beliefs……….maybe the reforms might not be so difficult ……………

“[O]verall the experience in Scotland [of community land ownership] shows that it leads to material and psychological benefits and increased community resilience.”

While the aims may be laudable, let’s see the evidence of “material benefits” (i.e. nett income) and stable, equitable governance first: it is too early to make such a judgment. Much of Scotland’s rural hinterland is beset with the legacy of a century or two of maximised short-term extraction of all resources, including people. Within the Highlands, what often remains is a class of “bonnet lairds” – super-crofters, with large holdings of multiple grazings shares, dependent on subsidised extensive stockholding – and a steadily diminishing underclass of minor crofters and cotters, who see more opportunities and greater stability in urban environments.

The super-crofters tend to make up the ranks of the Crofting Commission’s Assessors, giving them significant control over the distribution of material assets and the authority to enforce that control. Many of the underclass are widows, or students who commit that most heinous of crimes, not keeping sheep because they’re away studying! Guess who stands to gain from calling in the Crofting Commission to deprive these people even of the paltry rights to land use that remain as their families’ main assets?

In such circumstances, community ownership can only exacerbate such social dysfunction. Is there any evidence that the flight of the rural disempowered from the land is being stemmed, whether in crofting districts or elsewhere? (The correct answer is: none.)

Brilliant wee film. Acknowledges that all communities are unique so processes will vary for each and continue to change and develop, whilst underlining the importance of collectives and the fundamentals of communities having power. Scotland is part of an international movement of autonomy against globalization.