The Mitterrand Plan

“In economics, there are two solutions. Either you are a Leninist. Or you won’t change anything.” — François Mitterrand

“In economics, there are two solutions. Either you are a Leninist. Or you won’t change anything.” — François Mitterrand

A turning point in the final fortnight of the referendum campaign was the news, breathlessly reported by the BBC, that stocks in Scottish banks were falling. What had been a mere threat of financial disaster became a reality for newscasters and for those voters who listen to them.

The actual movement in price was modest and the story overhyped, but the fear it spoke to was real and rational. Ever since Nixon moved the world to a system of freely tradeable currencies in 1971, every country has faced the threat of capital flight. Capital flight is when investors pull their money out of a country in tremendous quantities. It cripples investment, brings about high unemployment, and often forces governments to rack up large debts to prevent a collapse in the value of their currency.

Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics and a member of the Scottish Government’s Council of Economic Advisors, calls this “hot money” – it flows into a country looking for a quick return, and leaves just as quickly at the first sign of trouble. Thus a minor political move – say, the decision of a Tory-owned financial institution to move its HQ – can lead to a bank run on an entire country. People who were involved in the movement for global debt justice, symbolised by the “Battle in Seattle”, will remember capital flight as one of the methods used to discipline developing nations and keep them on the neoliberal path. What is less well known is that capital flight came to Europe first.

In April 1976, James Callaghan became Prime Minister. Harold Wilson had resigned after the Labour left rejected his economic programme, and Tony Benn and Michael Foot were in government. They pursued the kind of Keynesian programme that Jeremy Corbyn now proposes: interest rates and government spending were used to fight unemployment, pensions and benefits payments rose, workers rights were strengthened. By September, currency speculators were hammering the value of the pound. Callaghan was forced to take a loan from the IMF, who demanded austerity as their price. Austerity and monetarism – the use of unemployment to control wage increases – began under Callaghan, not Thatcher.

Social Democracy had been so successful that it was undermining profits, and in the 70s and 80s European voters were forced to choose between dismantling Social Democracy to save profits, or moving towards Socialism. The same dynamics played out across Europe, and as in Britain, French voters tried moving left first.

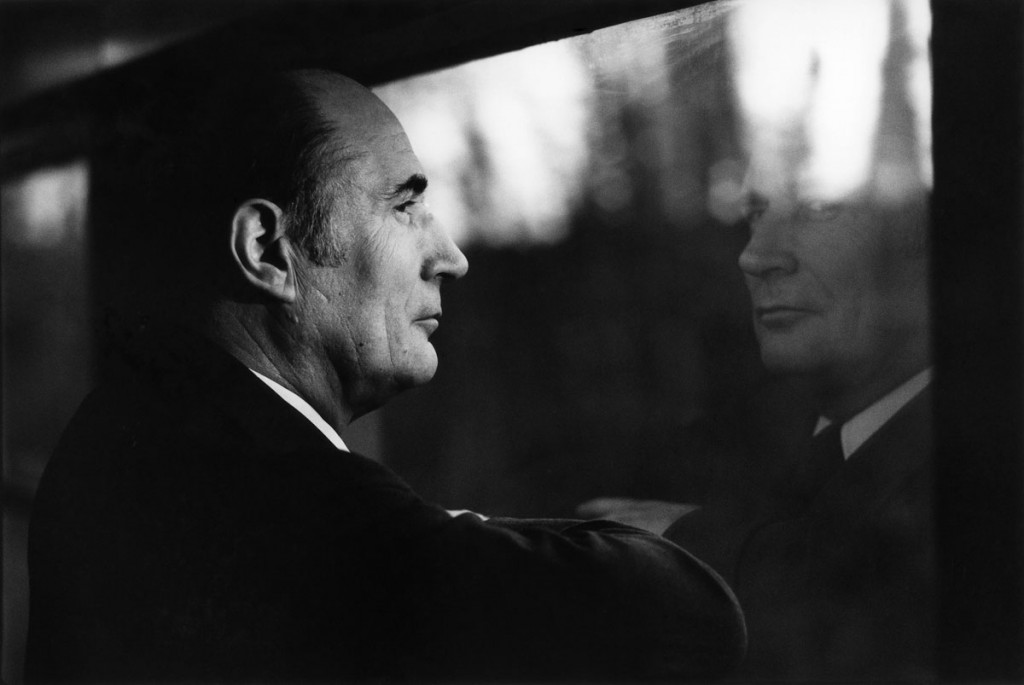

In 1981 Francois Mitterrand came to power with a radical programme for a peaceful transition to Socialism. Arguably his experience tells us what might have happened if Michael Foot’s Labour Party had beaten Thatcher in 1983 and implemented Bennite (Corbynite?) policies. Industries were nationalised, welfare spending drastically increased, a wealth tax introduced. For the first time since world war 2, capital-C Communists formed part of the government. Sadly, Callaghan’s experience replayed itself. By 1983 capital flight and a collapsing Franc forced Mitterrand to turn to foreign loans, with austerity as the price demanded by creditors.

The implication is stark for the European left: voters chose Socialism, but in a world of globalised finance no one country can be a social democracy of the kind we saw from 1945-1979. The only countries who can stand up to the global financial sector at all are the likes of America, China, and Brazil – giant countries, near-continental in size. Even posterchild Iceland restricted itself to jailing local spivs in the wake of a complete collapse. It did not and can not disentangle itself from the global banking system.

There have been two main responses to these uncomfortable facts: surrender and denial. Under Clinton, Blair, and Hollande, Social Democrats abandoned any challenge to centralised private ownership and concentrated wealth, instead focussing on post-market income redistribution. This led to spiralling inequality, because wealth produces so much income that it cannot all be redistributed.

Meanwhile the radical left has been gripped by denial, preferring to blame our failure on individual bad people, from Thatcher and Blair to Sheridan and Tsipras. This is a tragic abandonment of the left tradition of looking for structural rather than individual causes.

Once we accept the lessons of the defeat of Social Democracy, we can start to draw up realistic plans. Prime Minister Corbyn or an independent Scotland will not and cannot restore the postwar settlement. In Scotland, we might manage to ape the atrophied and weakened Social Democracy that still exists in Scandinavia. At a UK level, even that is impossible without first repressing the City of London, which would devastate tax revenues and the balance of trade.

No policy, no matter how radical or well-intentioned, can avoid these problems. Social Democracy worked so well that it forced a crisis, a revolutionary situation. It failed for the same reasons that every attempt to build socialism in one country has failed: capitalist powers combine to blockade and if necessary invade any threat to the system. This begs the question of how we avoid denial without surrendering. The clue might lie in Mitterand’s new policy after 1983, to pursue European integration at all costs.

Capitalists have always had a contradictory relationship with the state. They need the state to create markets and defend them from the poor (“For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor … It is only under the shelter of the civil magistrate that the owner of that valuable property … can sleep a single night in security.” – Adam Smith), but a state powerful enough to make a market is powerful enough to regulate it and to redistribute wealth from rich to poor.

Socialists face the same dilemma as the capitalists: we want to abolish the capitalist state, built as it is to defend the interests of the powerful, but the state is one of the few weapons capable of matching the power of the capitalists.

Capitalists must always build a state large enough to create the markets they need. For a common market across the British Empire, capitalists needed the British Imperial state. For a common market across Europe, capitalists have created the outlines of a federal European state.

While the EU is currently an enemy of Social Democracy from Scotland to Greece, the EU is also the smallest possible state capable of implementing Socialism or even Social Democracy in Europe.

There is a tendency in Britain to blame “the EU” as though it is a government apart, but in fact EU policy is largely driven by national governments in the Council of the European Union. The so-called European Parliament is actually a second chamber like the House of Lords. It is the national governments who appoint the Commission and the national governments who control the equivalent of the Commons. We have a right-wing EU because we have right-wing European governments.

If we want to match the power of finance capitalists and end austerity, our only hope is an international movement to win an anti-austerity majority of European governments. If we want Socialism, we must win a Socialist majority across Europe.

Wonderfully insightful piece of writing. Therein lies the reason I love Bella more than any other alternative media site.

yes, brilliant idea to ‘reprint’ this now.

To me, it makes it really clear

(1) Why voting to stay in Europe is vital, and

(2) Why Bella’s continued existence is vital

This article conflates Socialism – the state control of the economy – with Social Democracy – which is based on a market economy.

But the point about Mitterand is well made. If a similar French experiment were made now it would not only be international depositors turning the screws, but the pro-market European Commission, ECB and the relevant treaties, that France would have to default on.

Certainly didn’t mean to conflate them. I think socialism in one country and social democracy in one country face the same challenges.

Also that some Swedish social democracts made a genuine attempt to take a reformist path to socialism, so the distinction between the two isn’t as simple as sometimes claimed.

Agreed. Post-war the distinction seems to become established. I don’t think any of the mainline parties, including Sturgeon SNP and Corbyn Labour, would describe themselves as socialist in the classic sense – the community rather than capitalists owning the means of production.

At best they would be like Mitterand or old Labour, with the state aspiring to own the commanding heights of the economy. Much more difficult now under EU rules.

I agree with the author in that Old Labour are gone. Corbyn might have a chance fighting on tuition fees but he looks like he has backed down on this as well.

The Greens and some Labour thinkers are big on their direct democracy as a new alternative but I find this becomes pretty insipid in practice and ends with poorly attended community groups arguing about bus stops.

Can a democratic, publicly owned central bank not mitigate against the power of rich Individuals and their control over money and global finance?

Given what is going on in financial markets, I wonder if China is now the target for discipline.

A good article that leaps into overkill with this…

“The so-called European Parliament is actually a second chamber like the House of Lords. It is the national governments who appoint the Commission and the national governments who control the equivalent of the Commons.”

The Parliament elects the Commission, and can also dissolve it. More power, such as shared control over budgets has been shifting to the Parliament from it’s co-legislature, and will continue to as the EU seeks democratic legitimacy.

The Commission isn’t the Council tho. He refers to the Council. There’s a point to analogy, but beyond analogy each political structure must be analysed on its own terms. Power analysis shows the Council holds way more power than the Parliament. That’s really the main thing. The Commission is a kind of semi-executive, which in parliamentary terms seems to concern itself with infrastructural management, statutory instruments, and compliance. The Governments however really drive policy. I think that’s the main point.

“The Commission isn’t the Council tho”

And nobody has claimed that.

Though if you were to ask the average voter, the overwhelming majority wouldn’t have a clue about the power structures of the EU, so perhaps, in an article like this, we should strive to be accurate on such matters.

I’ve no idea where your ‘power analysis’ comes from either by the way. Going to enlighten us?

The EU parliament is a source of potential power for the left and the weak link for neo-liberals. The EU governments now accept that the leader of the largest group in the EU parliament should be the Commission President. This is a potential route for the left to influence the direction of the EU. Imagine a bold united integrationist left that was able to stand on a programme and become the largest party committed to a social Europe and an extension of democracy. The Commission could be used as a democratic battering ram by the left to transform Europe. Such a left would of course quite likely have allies amongst key states. Some would object but used skilfully other states would reach an accommodation depending on the balance of forces within their own territory.

It wasn’t the govt spending in the 70s that was an issue but rather the peg to the dollar.

Very interesting. Your analysis of the issue of capital flight is really good. Still, I think the political conclusions at the end just seem like a deus ex machina (“global capitalism threatens democracy, we need the EU”). You might be correct that we need a pan-European socialist state to effectively implement sustainable economic planning. That is *not* an argument for the EU. The notion that the EU is a kernel of a future socialist multi-national state is just not plausible or supported by any evidence. Its structures are not incidentally undemocratic and ‘right-wing’, such that they can be fixed by a few election victories: they are intentionally structured in this fashion. They are *intended* to operate outwith democratic control so that the machine rolls on apart from any ‘democratic shocks’ cf ‘Lisbon Treaty’, Greece, Spain, Italy etc. Of course any situation could be improved by left-wing governments. Left-wing governments would improve the UK – is that an argument for the Union with London? No. So why is it an argument for Union with an even more undemocratic, distant and unaccountable structure like the EU?

The EU can still be overruled and the extent of power in the centre much less than the UK. If the UK ceded as much power to the EU as Scotland does to the UK we’d leave no question. Scotland could easily ignore EU legislation that inconvenienced them as Southern Europe does on occassion.

The EU is becoming controlled through coalitions of countries. The big shift was when reactionary oligarchic countries in the East joined, many of whom are the Tories biggest allies. Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, etc. Western Europe was traditionally much more middle of the road. Counter intuitively, it is precisely because of democrscy you have this loony right-wing switch. Many of these countries are barely democratic with corruption on massive scales. The issues in Poland surfacing now are extreme but the tip of the iceberg.

That would be no reason to dismiss these countries and particularly the people there as ‘crazy’ but a great deal of EU policy is determined by them. The EU being baw deep in ethnic conflicts in the former USSR is the most obvious. The situation in Ukraine would be a lot less tense if these incompetent regimes did not a Russian bogeyman to keep the proles in check.

The tories were the biggest advocates for EU enlargement, makes you wonder if they saw the issues this would cause.

I think part of the problem is that we tend to talk about the extremes: a greed-is-good capitalist economy at one extreme and a centrally-planned socialist economy at the other. Both disastrous in the long-term.

Interesting that you quote Smith. Smith is widely quoted out of context by economists and politicians to justify all sorts of nonsense (e.g. Invisible hand of the market bs). They get away with this because hardly anyone reads Smith. Your quote is from Book V of Wealth in which he discusses the three duties of the sovereign. These were first outlined at the end of Book IV:

Your quote comes from the section discussing justice in which he speculates about how systems of justice developed and then discusses how justice might be administered fairly. A central argument of the book as a whole is that the wealth of the nation (i.e. of the citizenry as a whole) is dependent on institutions that ensure justice for all. Note, however, that Book IV is a critique of the mercantile economics of Smith’s day, describing how the wealthy merchants bend government, the institutions of law, etc. to serve their own interests against those of the public. The nature of the economic system is somewhat different today but the political problem is still the same: what institutions support the generation of wealth and restrain factional collusion so that the general security and well-being isn’t sacrificed to the interests of a few? Don’t expect practical answers to come from either socialist or capitalist ideologues as both in their own way are masters of factionalism.

Also, good point about some of what we now consider to be neoliberalism starting in administrations pre-dating Thatcher and Reagan. For more on the history see Daniel Stedman Jones’s Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics. One of the tragedies is that Keynes died when he did immediately after Bretton Woods. The so-called Keynesians that followed weren’t half as smart or pragmatic as Keynes himself.

I also agree with the general point about countries being entangled. This is not new. Back in the 18th C. nation states worried about the influence and power of companies like the East India Company (a major target of Smith in Wealth and the model for the global mega-corporations to come). Smith is often used as a justification of small government but he was against the power of all large institutions (religious, economic, etc.). Government, although it is often heavy-handed and infringes on individual liberty in many negative ways, was in fact preferable to corporate or religious institutions. The former at least serves the public interest in theory; the latter are inherently factional.

An acute comment, if I may say.

“The former…the latter..” Smithian! Having just finished “Moral Sentiments” and closing in on “Wealth” I am struck by what a humane man Smith seemed to be. Armatya Sen in his intro to “Sentiments” argued it was at least as important as “Wealth”, but it would seem even fewer of the neoliberals have read it.

It seems to me that Smith’s thought has been purloined and bastardised by economists and politicians, just as you say, for I can find little to support their appropriations of his work. Quite the opposite, for as well as his critique of “global” entities and his support for justice for all, among other things, he deplored monopolies which served only the interests of the monopolist, he was against slavery, he noted the disastrous consequences of european migration to the Americas, he commented on the iniquity of inequality and argued that “Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.”

All of these issues are alive and well today.

1. As Paul Mason often says: ether we are at a 50-year transition between different historical “phases” of capitalism or we are at a 500-year transition between the capitalist mode of production and another mode.

2. If we are at a 500-year transition, then this is a problem for reformist politics because even if a country elects a government which aims to embark on the transition by itself, the international isolation that country would experience would make the transition impossible.

3. The task of ensuring that any 500-year transition we are about to undergo is progressive in character is almost impossible to achieve through the ballot box, due to different election cycles across the continent of Europe, along with the domination of the capitalist class.

4. Obviously, the historical precedent is the French Revolution, which resulted in a convulsion across Europe that (along with the industrial revolution in Britain, of course) facilitated the transition from feudalism to capitalism

5. As Immanuel Kant remarked at the time of the French Revolution, it was an event which inspired revolutionary enthusiasm across continental distances and which then ensured that surrounding countries achieved the appropriate transition. Contrast this with the failure of the enthusiasm of Syriza’s election in Greece to have much of an effect at all (therefore demonstrating how different election cycles across the continent function to prevent a progressive transition)

6. If we are at a 500-year transition, then we are either looking at a progressive transition to a post-capitalist (perhaps even communist) economy or, alternatively, a neo-feudal rentier economy characterised by even rawer forms of class power than we know now. Therefore the stakes cannot be higher.

7. Europe therefore needs a revolution in at least one country to inspire the entire continent and to get out of its current mess (I would contrast this approach with Yanis Varoufakis’ idea that progressive left forces need to “retake” the EU – again, the problem is: how to do this in a continent of different election cycles?).

8. Could post-referendum Scotland be the site of this revolution? Yes, but equally, I think the whole of Britain could be the site of this revolution (particularly once Labour has imploded under the weight of its current contradictions) – personally, therefore, I am for holding back on pushing for independence, particularly in the light of the SNP’s excessively gradualist approach. But, equally, I do see the revolutionary case for a more militant left-wing push for independence (indeed, I was making that case for a while). Whether we are better off pushing for a Scottish revolution or a British revolution is a strategic question, the answer to which will only become clearer with time. (As Fredric Jameson says, politics is the art of opportunism, not principle.)

9. RISE is obviously not a revolutionary organisation (although there are some revolutionaries lurking within it). But, then, I think that brings us back full circle – are we at a 50-year transition point or a 500-year transition point? And how different should our strategies be depending on the answer to that question? If the two possible answers to this question lead us to two totally incompatible “strategy sets”, then those revolutionaries within RISE (and the Scottish left more broadly) will probably have to embark on their own project. A scary split, perhaps, but on this rare occasion I am with Zizek on this question – sometimes a sectarian split is necessary to keep radical politics alive.

A great article with plenty to think about. Mitigating the risk of capital flight is surely the biggest and most important challenge that the SNP has to tackle before moving for a second referendum.

Some very good comments made too especially by Alan who picked up on the Adam Smith point. I think that there’s a full article there on taking Smith off of the right wing libertarians and seeing what he has to say that is relevant for all of us.

There are those who decry “Socialism in One Country”, but it is still better, no matter how badly implemented, than “Socialism in No Country”. The American elite were absolutely terrified of the dangerous example of Cuba, and of the revolutionaries it created, such as Che. A massive counter-insurgency and counter-Revolutionary program engulfed Latin America for 30 years after Fidel took power. That is simply factual. Ultimately, it failed, as it left behind an entire continent of rage and and opposition to the Americans, which is historically permanent. The consequences of this are now manifesting themselves, as Che Guevara’s powerful observation, that “America will destroy itself in 100 Vietnams” comes true. The recent chain of wars in the Middle East and elsewhere have bankrupted America, wrecked its social organization, and impoverished a large part of it’s population. It is now in a major internal crisis and cannot survive long term in it’s present form. Europeans tend to forget they are just 20% of the Global population, and that the big struggles are happening elsewhere. Ultimately, what matters is what happens Globally, in a World where the great mass of the people live in impoverished third world countries, and really are, as Fanon said: “The Wretched of the Earth”.

So where does this leave Scotland?….In, I think, a rather interesting place. It has a long radical tradition, leftist ideals in a large portion of the population, and many internal problems, such as land reform and economic destruction by the UK Government, and much else. It has now elected, twice, a transitional Government, (SNP) for a transitional state. Unlike most small states, it has natural resources on a very large scale, and could, if independent, resist Hegemony by the Global system as they need these resources, and would have to tolerate some national autonomy. An autonomous Government would have some room for manoeuvre. Because we are now on the edge of a series of crisis in Europe, and Globally, and the general global system is itself in crisis, there is room for some considerable level of reform and restructuring, carried out by a radicalised left wing Independent Scottish Government. If France had had nearly three times the oil reserves of Kuwait, (Scotland has) then Mitterand would have had considerable elasticity and power in dealing with the global system. So would Scotland. The Greek idea, of international solidarity, cooperation, and resistance to the neo-liberal Hegemony, would, and could, work, if the key European states were able to install leftist administrations. If not, Scotland could still exist, as an independent dangerous example to the rest of Europe. All this sounds very ideological, but is merely to state the obvious. So Scotland has a hard choice. It can remain in the UK system, or leave, which will require considerable hardship and struggle, but the alternative would be further serious erosion and impoverishment, as in Greece, unless it did so. The EU Referendum is near, and it lookes like an exit poll. At that point, there is an internal crisis in Scotland and the UK, and handled correctly, an opportunity for a clear vote for independence. I think there would be a YES vote to leave. At that point, we are in another ball game, and a real struggle, but the alternative is rather grim. Sometimes you have to make a stand, and resist, fight, and win.

Also, if you have a state of over 350 million people spread of 30 countries it would struggle to be democratic in any meaningful sense. In a state of 5 million people 200,000 might need to be convinced that something is wrong in order to bring about change in the country or state. In a political union of 400million spread across 30 states and many more languages it would be near impossible for policy to come from people. The idea of popular sovereignty may work well in an individual state but be meaningless within the wider union. Maybe there is a trade off here. Can a democratic central bank, publicly owned and run, in each state mitigate the effects of global capital and the people who own it?

Hi Gordie … have a look at the work being done by Positive Money,the clip below being a simple introduction, the other video clips on the site go into much greater detail:

http://positivemoney.org/about/

I see myself as somewhat illiterate against the article and the informed comments that have followed it, but pulling together an EU left majority seems to me a very big ask, the electoral cycles across the EU being a major factor as already commented on, and even if accomplished will not only face fierce opposition, but will likely face a backlash from the right and the markets as the struggles arise.

So, can we in Scotland in any way act as a pathfinder, on independence we will face a debt burden, and that will affect the levels of struggle we will face, and we still have to resolve the currency question, the markets (whether we like it or not) will challenge us … and taking those aspects into account is where I think the proposals behind Positive Money deserve serious consideration and debate, and relating their work to the article, the thinking behind the proposals are gaining international interest and research, and from both the left and the right.

On the Mitterand quote about the Leninist solution: I came across this in an interview with Alain Badiou:

Which reminds me of Foucualt’s observation in The Birth of Biopolitics (pp. 91-93), about the absence of an autonomous socialist art of government. He observes that historically socialism has only been implemented by being connected to other types of governmental rationality: liberalism (where socialism functions within as a palliative) or a hyper-administrative police state.

I’m never quite sure if Foucault was celebrating or critiquing neoliberalism in the College De France lectures (The birth of bio-politics). I sometimes get the impression that he was doing both. He certainly seemed to admire some of the key thinkers in neoliberalism; Hayek and Becker for example.

I read Biopolitics cover to cover and I don’t recollect a single place where he might reasonably be construed as celebrating or admiring neoliberalism. Where? Recent accusations that Foucault had a positive view of neoliberalism, stem from Zamora’s article in Jacobin and a subsequent book of essays on Foucault and Neoliberalism edited by Zamora and Behrent. For a detailed critique of Zamora and company see Colin Gordon’s commentary: Foucault, neoliberalism etc.

Gordon quotes Michel Senellar, the editor of the lectures, who is worth re-quoting:

It’s now more than 35 years since Foucault’s biopolitics lectures and it’s hard not to conclude that the Left’s “critical culture” is still having trouble coming to terms with the challenge of neoliberalism and remains “singularly ill-equipped to respond”. See, for example, Philip Mirowski’s Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown, a savage attack on the American version of neoliberalism and the failures of the Left. There is a need for a little more “critical attentiveness to the present”, of the sort exemplfiied by Foucault, so that the “possibility and necessity of fresh acts of inventiveness” can be grasped. The tired old socialist intellectual frameworks and their associated rhetorics don’t cut it and haven’t for a very long time.

Alan,

The argument that Foucault was an admirer of ne0liberalisms design is made by a number of academics including Mirowski, who provides a critique of Biopolitics in the book you just mentioned – the highly enlightening chapter is entitled Everyday Neoliberalism. My other source was Mitchell Deans’ Michel Foucault’s ‘Apology’ for Neoliberalism’, which was in the Journal of Political Power. Ewald (I think) who was one of Foucault’s doctoral students also accused him of being an apologist (I think that was the term) for neoliberalism.

Having said that we could trade sources all night on Foucault. In terms of my own thinking, as you rightly point out, Foucault provided a powerful critique of socialism and taking his critique to it’s logical conclusion I was left with the feeling that there was no credible alternative to capitalism or neoliberalism. Fukunyama’s end of history was for me a realisation that we are living through ‘the end of revolution’ in the West. As you know Foucault’s insight into neoliberalism was very prescient mainly because he engaged with the work of neoliberals. When I read his analysis of Becker about the ways in which all relations are marketised, including the construction of an entrepreneurial self, I was left with the conclusion to paraphrase Foucault that neoliberalism was a means of thinking about power without discipline? That for me is pretty fascinating, and comes close to suggesting that Foucault was an admirer of neoliberalism. From a Foucauldian perspective, I would say that I am too.

Frank,

I agree with your about comments about engaging with the work of neoliberals. That’s why he has so many insights on what’s new and distinctive about neoliberalism and why the analysis has been so fruitful. And I agree on the importance of of the analysis of Becker, the transformation of all relationships into market relationships, and the construction of an entrepreneurial self.

As far as Foucault being an admirer of neoliberalism I’m going to stick with Senellar’s “exemplary abstention from value judgements” unless someone has textual references to Foucault’s work that provides good support for a contrary reading. Neither Dean nor Mirowski see Foucault as a neoliberal or advocating neoliberalism and their own work on neoliberalism, as both acknowledge, builds on Foucault. Dean notes elsewhere that “The vast bulk of Foucauldian commentary and analysis would reject the idea of an affirmative relationship between Foucault and neoliberalism.”

It also rather misses the point of Foucault’s work to accuse, as some do, Foucault of being a card carrying this or endorsing that, whatever those things might be. It misunderstands his analysis of power/knowledge and the type of critique that analysis makes possible. Foucault himself comments on the desire to stick political labels on what he’s doing (see the Polemics, Politics, and Problematizations Interview in The Foucault Reader):

Others worth reading on the matter include Will Davies (“First of all I have never read Foucault as someone who’s promoting neoliberalism. The controversy strikes me as a fairly tribal attack on somebody who has always annoyed the socialist left…”) and Terry Flew (“Foucault’s own complex, nuanced reading of what he would term neoliberalism has long been at risk of being subsumed into a more generic neo-Marxist critique of capitalism….”).

Columbia University has been holding a series of seminars on all the College de France lecture series given by Foucault. Last month was STP and this month, today, as it happens, is The Birth of Biopolitics. This can be watched live here. The associated materials are worth reading. See especially Harcourt’s introduction and the transciption of a talk Ewald gave last September. Ewald:

Great piece. Alistair, and I agree with your description of the EU, because PACE Boab above, the EU Parliament is not a plenipotentiary insititution. As you rightly say, the EU is run by national governments – all of the Commissioners are appointed by national governments – and so of course it cannot be a truly pan European institution…and it cannot fight for the common European interest…

…it used by called the European Economic Community, which is a much more fitting billing than the European Union, because there is no union to speak of. I am 46 years old, I lived most of my life outside of Scotland, and I have only been able to vote at one single general election in my life, which was the GE of 92 – I voted SNP. I have paid my taxes all my life.

The same is true for Europeans in Scotland. We have, at Edinburgh University, in the Hispanic University department, one of the major world experts on contemporary Spanish literature, a Greek who speaks about ten language, a veritable genius of man, and he doesn´t get a vote either…so enough of this farcical sham about the EU being democratic…it is not democratic and it exists to boost pan European trade, period…

As for the historical moment, well, we are well on our way to techno-fascism. The only hope is that the technology can help the Left too. As Gramsci said, “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will…”

Better to be a Leninist than a defeatist.

We all follow the yanks and that can only mean disaster.

No one really seems to know what neo-liberalism is in any categorical sense- for me its more or less a consistent set of economic practices that liberate the flow of capital from the geographic limits of space and time. It’s really a description of the financial global elites institutional opportunism & not a coherent ideological system that provides positive solutions to the perennial ‘problems’ of the human condition. Neo-liberalism is a mythological ‘system’- in that sense it did not survive the financial meltdown- mainly due to the fact that it doesn’t exist: the last few years have simply been a manifestation of how the same old monied elites have survived & insured financial solvency by being enabled by governmental levers. These national governments, including the UK, have been conspiring with these global elites, to empower them domestically & also limit resistance- these financial elites have used the free reign they have enjoyed for the forty years by constructing syphoning structures that have facilitated a vast transfer of public money to private interests. Neo-Liberalism as a set of practices is a machine for producing inequality. Its hard to see how so-called Neo-Liberalism can fail: it has the capital, owns the banks, is enabled by domestic governmental state conspiracies, the whole game is rigged in their favour- why does the left persist in fighting Capitalism on its own terms? Why did the communist revolution under Lenin continue to use the anachronism of money? How can you achieve what is beyond the present limits of capital by seeking change within a capitalist system? How can we have a modern rational civilization if its founded on an ancient feudal concept like money? This seems contradictory to me: surely we on the left need to elaborate a system that in no way participates in our enemies system- a capitalist economic system that operates through a basic unit that expedites debt & financial dependency-& finds a way of simultaneously traducing the reality of capitalism & most importantly offer an alternative that transcends the primitive concept of money & capital debt.