Nowt so Queer as Folk

There’s nowt so queer as ‘folk’: is the word folk useful anymore? by Jamie Chambers.

There’s nowt so queer as ‘folk’: is the word folk useful anymore? by Jamie Chambers.

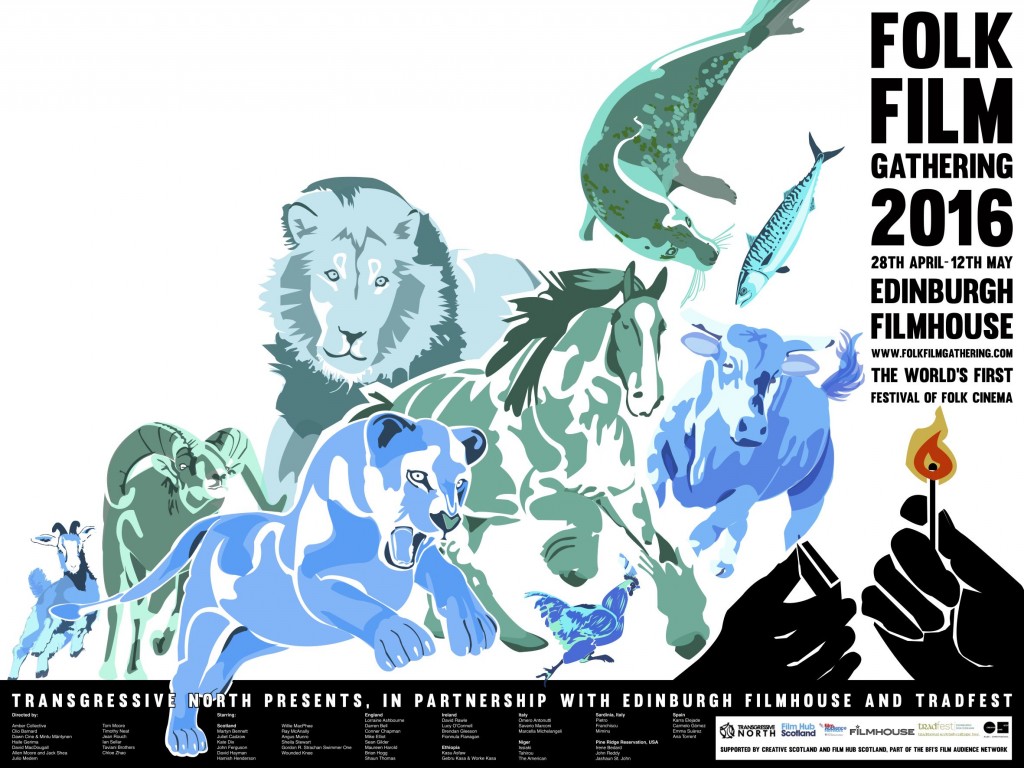

The Folk Film Gathering – the world’s first folk film festival – takes place from 28th April to the 12th May, at Edinburgh Filmhouse and the Scottish Storytelling Centre.

Putting together this year’s programme for the Folk Film Gathering I’ve found myself thinking a lot about the word ‘folk’: about what it means and whether, in 2016, it’s still a useful word for progressive political projects in Scotland and further afield.

We seem to use the word ‘folk’ a lot in Scotland; and whilst every one of us (myself included) seems to think we know what it means, a look round Scotland and the West more widely serves to illustrate that ‘folk’ means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

All of the films at the Folk Film Gathering this year enact their own ideas of ‘folk’. A skim through our programme suggests just how broad the ‘folk’ catchment is: whether its the early 80’s Hebridean shepherding community in SHEPHERDS OF BENERAY, the 40’s Orcadian fishermen in VENUS PETER, or the 90’s Tyneside trotting community in the Amber Collective’s brilliant EDEN VALLEY, and the Bradford scrap metal business in 2013’s THE SELFISH GIANT; or the farm labourers in 70’s Ethiopia in Third Cinema classic HARVEST 3000 YEARS, the Sardinian shepherds in PADRE PADRONE and TEMPUS DE BARISTAS, or the residents of the Native American Pine Ridge Reservation in 2015’s SONGS MY BROTHERS TAUGHT ME.

So if our programme is anything to go by, ‘folk’ can be rural and urban; pre-industrial, industrial and post-industrial; can embody an address to the present, to the past, or both; can be traditional, contemporary, or both; it can be rooted and bounded, or diasporic and hybrid, or – once again – it can be both.

It’s a strange and powerful word that can seemingly straddle such a dizzying spectrum of different cultural and historical locations, and attempt to bring them into some sort of alignment. A Utopian word then, yet a Utopia teetering on the edge of terrifying darkness: for just as the word ‘folk’ has been associated with some of the most inspiring Leftist struggles for recognition and political revisionism, so it has also been associated with many of the darkest moments in history. As the Scots film critic Colin McArthur sagely remarked to me after last year’s Gathering, a Folk Cinema should be careful not to become a Volk Cinema…

If ‘folk’ has any stable implications at all, it would seem to be subaltern (popular / working-class / ‘low-brow’) on the one hand, and collective (communal / plural / choric) on the other. Yet, trying to excavate any stable sense of meaning from the word ‘folk’ recalls Raymond Williams on the idea of ‘the masses’:

To other people, we also are masses. Masses are other people. There are in fact no masses; there are only ways of seeing people as masses… The fact is, surely, that a way of seeing other people which has become characteristic of our kind of society, has been capitalized for the purposes of political or cultural exploitation.

Similar can be said of the word ‘folk’: a way of seeing people in different ways, for very different purposes. You only need to look through Scottish and British politics over the past few years to find ‘folk’ in the employ of highly divergent political projects. To me, it is implied (if not always voiced) in the Yes Campaign’s ‘Come All Ye’ sense of grass-roots collectivity; I see it in the inclusivity and collectivity of Common Weal’s ‘all of us first’, and the very idea of a ‘common weal’ itself. Beyond IndyRef see it in the grass-roots formation of Scotland’s new media, in the free sharing of information, and the changing solidarities between different parties and institutions of the Left.

Elsewhere, however, the word is a mainstay in the vocabulary of Nigel Farage, who so frequently returns to a refrain of “ordinary folk, ordinary families that are paying the financial price”. Whilst IndyRef’s appeals to ‘folk’ were almost always inclusive, Farage uses the word exclusively; to distinguish a white, indigenously British ‘Us’, from the incoming threat of ‘Them’.

As I wrote for Bella last year, our arts collective Transgressive North founded the Folk Film Gathering upon Hamish Henderson’s revisionist idea of ‘folk culture’, and the subsequent, Utopian celebration of socialist, cross-cultural solidarity buoying the world folk revival. Hamish’s own, particular use of the word ‘folk’ takes a lot from Gramsci’s famous Observations on Folklore:

Folklore must not be conceived as an oddity, a strange, ridiculous or, at best, a picturesque thing; rather it might be conceived as something very serious and to be taken seriously. Only in this way will its teaching be more effective and better develop the culture of the great popular masses, and the separation between modern culture and popular culture or folklore will disappear.

It’s illuminating to think of Hamish’s summed body of work – his activism, research, poetry, and enormous, epoch-defining contribution to Scottish culture – as being an address to this separation between bourgeois and ‘folk’ culture. For indeed, there’s no more resonant symbol of Hamish’s revisionism (particularly when thinking about cultural events in Edinburgh) than the 1951 People’s Festival Ceilidh at Oddfellow’s Hall: the opening up of the hitherto exclusively bourgeois stages of the Edinburgh festival to the working class, subaltern, ‘lay’ cultures of Scotland. A similar case for a folk cinema seems self-evident to us in Transgressive North: of opening up the privileged arena of cinema to popular experience and concern.

In a passionate indictment of anthropology in the 80s, Johannes Fabian condemned the way in which Western thinking about subaltern communities so frequently sought to distance subaltern experience as somehow behind, below or outside the status quo. Fabian uses the word ‘allochronic’ to describe the way in which ‘folk’ communities are framed by Western discourses as divorced from the present, dialectical moment; backward, primitive, out-of-time, uncomprehending and therefore less deserving of political priority or recognition. In these terms Hamish’s work can be seen as trying to subvert bourgeois, ‘allochronic’ framings of Scottish popular culture, by provoking encounters situating Scottish popular culture both literally and figuratively on a national and international stage.

Whilst Fabian’s ideas help us understand the Hendersonian, Gramscian imperative to attack separations between bourgeois and popular culture, they also point to problems with the word ‘folk’. Recalling Raymond Williams (and ‘folk’ as a way of seeing people), it’s easy to point to a heavy usage of the word that’s overwhelmingly defined by romanticism, exoticism, nostalgia and paternalism; ‘folk’ as kind of collectivized noble savage.

The hint of exoticism in the word ‘folk’ really worries me. There’s a current trend of ‘folky’ coffee-table books (featuring semi-ethnographic pictures of subaltern communities in traditional costume) that seem to play directly to bourgeois appetites for exotic images and aesthetically pleasing primitivism. I worry that a folk cinema might be in danger of satisfying similar tastes; functioning as a form of social safari or class tourism complicit with neo-imperial and neo-colonial ideology. I was shocked recently to hear a filmmaker who should know better discussing how poor Eastern communities ‘presented themselves’ much better to the (Western, white, middle-class) eye than disadvantaged communities in Scotland: a disgusting and racist insinuation of a bourgeois ‘aesthetics of poverty’. Considering this in regard to our programme makes me worry: are the films of the Amber Collective, depicting the post-Thatcher struggles of de-industrialized working class communities in the North of England, somehow less aesthetically pleasing and less successful with British cinema-going audiences than the rurally-set films of the Taviani brothers? Are the films of Garry Fraser less pleasingly ‘folky’ to the bourgeois palate than WHISKY GALORE or THE MAGGIE? The notion of a ‘folk aesthetic’ – images of subaltern experience structured for the delectation of bourgeois cosmopoles – is intensely troubling, and would seem, for events like ours, very dangerous to cater to.

Indeed, for the native American political theorist Vine DeLoria, the word ‘folk’ itself stands for distanced, backward and ‘allochronic’:

The anthropological message to young Indians has not varied a jot or tittle: Indians are a folk people, whites are an urban people and never the twain shall meet.

Back in Scotland Malcolm Chapman has similarly criticized the way the word ‘folk’ distances the people using it from the people it is imposed upon: “the folk that are in possession of the kind of knowledge that [one] might choose to call ‘folklore’, have no … idea that within somebody else’s discourse their knowledge is so peculiarly marked”. As it is a “categorical requirement” of folklore that it should be the “pre-rational memories of former days and ways”, “any attempt to restore to ‘folklore’ an epistemological status equal to the knowledge that, say, a folklorist has, will be impossible, however good the intention”.

Back in Scotland Malcolm Chapman has similarly criticized the way the word ‘folk’ distances the people using it from the people it is imposed upon: “the folk that are in possession of the kind of knowledge that [one] might choose to call ‘folklore’, have no … idea that within somebody else’s discourse their knowledge is so peculiarly marked”. As it is a “categorical requirement” of folklore that it should be the “pre-rational memories of former days and ways”, “any attempt to restore to ‘folklore’ an epistemological status equal to the knowledge that, say, a folklorist has, will be impossible, however good the intention”.

DeLoria, Chapman and Fabian raise difficult questions for the word ‘folk’. Are Gramscian, Hendersonian attempts to provoke recognition for subaltern communities innately subverted from the outset by the identification itself of a ‘folk culture’? By using the word ‘folk’ do we distance whichever community we are talking about, and somehow push ‘them’ outside of the present, dialectical moment where ‘we’ stand ourselves, the moment where political priority is established? I’d personally hope it remains possible (if difficult) to at outplay least partially such determinism. The critique bites deep, however, and is not easily dispelled.

Another set of problems arises when we consider how the word ‘folk’ allows the local and the specific to aspire to the global and universal; dubbed ‘the folk’, a very particular people becomes The People. It’s all too easy to see how appeals to ‘the folk’ in nativist discourses can lead to exclusion and fascism. The word ‘folk’ (or volk) allows a given people to lionize themselves as The People and thus potentially marginalise those that the word excludes. To paraphrase Mark Salber Philips, the question with the folk ‘Come All Ye’ is always ‘how wide is the We’?

Yet this question of ‘folk’’s dual address to local and global also belies the word’s potential for progressive political projects. For Hamish Henderson, ‘folk’ indeed implied a sense of cultural specificity; a commitment to the particular concerns of working class and subaltern communities in Scotland – and rightly so. Crucially, however, Hamish’s conception of folk was not parochial or exclusive, but looked outwards to Europe (and the Italian partisans), to America (and the dustbowl), to Africa (Rivonia) and beyond. Put differently, Hamish’s ‘Come All Ye’ stretched from Springburn to Nyanga.

Such a Utopian sense of universalism maybe seems outmoded for contemporary Leftist discourses understandably dominated by politics of location and identity. Viewed from within the fraught arena of contemporary identity politics, universalisms seem naïve at best, and pernicious and duplicitous at worst. James Clifford describes how:

A very human being becomes a humanist. But the privilege of standing above cultural particularism, of aspiring to the universalist power that speaks for humanity, for the universal experiences of love, work, death, and so on, is a privilege invented by a totalizing Western liberalism.

Any yet, a growing number of commentators on the Left seem to be taking universalisms back off the shelf; thinking about ways universalist approaches can pragmatically be used in the service of socialist projects that are increasingly dissatisfied with action performed merely at a local level. As Jimmy Kasas-Clausen wrote recently, Alain Badiou, Jacques Ranciere, Paolo Virno, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri converge in making claims of universality and global action central to their conception of Leftist politics. Kasas-Clausen describes how, by saying ‘there is only one world’, we allow ourselves to act on the world as if it were one; an approach mirrored by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’ recent denunciation of hyper-localism (which they ironically dub ‘folk politics’!) in Inventing the Future. Here on Bella, Katie Gallogly-Swan wrote two months ago that when Bernie Sanders:

speaks of ‘together’, it isn’t just about Americans. For me it’s about the international movement for justice and the role we all play in enacting change. With a strong dose of defiant hope and passion, we shouldn’t be interested in simply making America great again, but in making the world great, movement by movement by movement.

The word ‘folk’ remains provocatively ambiguous: extremely powerful and yet considerably dangerous. The longer you roll it around on the tongue, the more it seems ambiguous and ambivalent, ready for co-option and articulation by any political project that can fit it for purpose. Yet somehow, despite an enormous, anxiety-provoking history of misuse, I’m still quite attached to it. For us in Transgressive North and for many others in Scotland I would imagine, ‘folk’ remain a pregnant symbol, a powerful image of collectivity and demand for the political recognition of marginalised communities that can potentially rally and align disparate socialist movements in complex, fraught, but essential dialogue.

And yet, I feel it’s important to keep the dissonance and anxiety the word provokes. The issues are real and remain to haunt any use of the word ‘folk’ and any possibility of a Folk Cinema. The Amber Collective, (whose masterful EDEN VALLEY we are showing this year, followed by a Q+A with the filmmakers) believe the ethical, cultural and political difficulties of making films with subaltern communities are an inextricable part of the process of making such films. The problems are to be lived with, worried over and struggled with, and not resolved. A perfect destination and a perfect film are never reached.

Others will disagree, but it would seem to me – as it obviously does for Amber, Clio Barnard, Chloe Zhao, and many of the filmmakers represented at the Folk Film Gathering this year – that its infinitely better to attempt to outplay the determinism and try.

Brilliant article. And the entire programme of events seems a necessary and very welcome to the dominance of ‘high’ culture at the Festival, wonderful though much of it may be. I found myself really wishing I could see the films discussed here. (Ditto last year’s offerings.) And I found myself thinking about cultural seclusion in a different sense, and wondering whether there might not be some way to open these up to others, like me, excluded from this particular discourse by location (I live a day’s drive from Edinburgh), purse (I have just the basic pension), or personal circumstances (I have chronic health problems which leave me bed-ridden much of the time). There must be many others similarly prevented for one reason or another, from seeing and discussing the films.

Yet we have the technology to make this possible. Might there not be a way to give access to the programme and discussion about its components in a curated presentation online?

I don’t know how many of the films involved are available online already, but what I have in mind goes beyond that, bringing them together, linked in some kind of programme, just like a ‘live’ festival, with a dedicated discussion area attached; the latter could be so important for the socially isolated.

I know that there are costs involved in putting on the festival as it stands, and that paying punters are essential to cover these. But it occurs to me that, in addition to the usual concessions, those who are financially excluded might be given free (or very greatly-reduced price) access after the series of showings at the Festival is over, and the market already fully ‘milked’ from those willing and able to see the films at the time of showing. This would allow much greater geographical (including behind the bounds of Scotland) and social access. Isn’t that what a folk film festival should be aiming for?

However, excellent, thought-provoking article. Bella at its best. And a great example, too, of contemporary Scottish culture, where politics is not a self-conscious, polite, not quite fitting in, we’ll need another chair, occasional visitor to the arts (as it seems to be south of the border) but is relaxed, fully and comfortably at home in the family, feet on the sofa, arguments (sometimes loud and furious) and all.

I think the inclusive sense of ‘folk’ remains dominant in Scottish discourse. Patrick Geddes believed that the triad of Place/Folk/Work provided a basis for social analysis which had universal application. From that perspective we are all ‘folk’, and under no obligation to be ‘ordinary’. I find the concept of ‘subaltern communities’ with its connotations of subordination and distancing far more alarming! All folk need to think global and act local.

Aye. There’s nowt so queer as people.

I recall Jack Shea showing us the product of his year-long sojourn on Berneray on celuloid at Edinburgh College of Art in the early 80s where he lectured immediately after. He described how forgetting he had promised to edit out the lamb castration by human tooth did lose him some friends at the Berneray public viewing.

In his film and elsewhere our ‘Folk’ commonly appear to hang on to existence by a thread. Or be already extinct or lost. I suppose this is a part of folk’s appeal. Often the folk were pushed to the margins where they struggled. It is the same today, as described on Skye by my friend Seonachan, bemoaning the never-ending exodus of youth from a place with no work. Must such go on for eternity?

For all its creativity under duress, I believe folk will produce more and better if communities at the margin are re-enfranchised and relinked to the heart of their nation when we reclaim the rents of land as Scotland’s. Under AGR, areas with low rental values will pay less than those with high rental values. Here is the resolution to a thousand years of oppression.