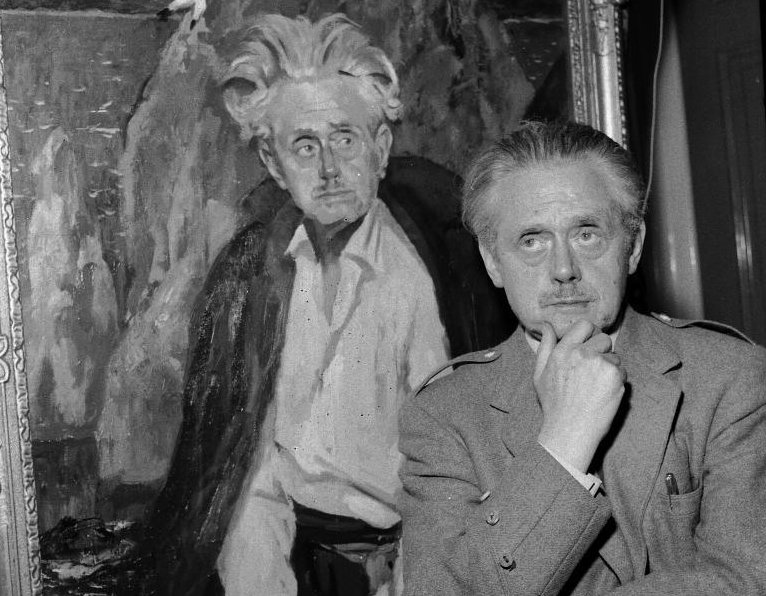

Hugh MacDiarmid and Prejudice

Hugh MacDiarmid was a fascist. As well as a communist, Scottish nationalist, Scots Republican, and Social Creditor. And – what is sometimes forgotten – often a great poet, too. Scott Lyall argues that supporters of independence need to acknowledge MacDiarmid’s fascist statements, but that the persistence of this debate tells us something much more revealing about the nature of modern Unionism.

Hugh MacDiarmid was a fascist. As well as a communist, Scottish nationalist, Scots Republican, and Social Creditor. And – what is sometimes forgotten – often a great poet, too. Scott Lyall argues that supporters of independence need to acknowledge MacDiarmid’s fascist statements, but that the persistence of this debate tells us something much more revealing about the nature of modern Unionism.

The recent front page story on Hugh MacDiarmid in The National (20 May 2016) sparked the usual round of social media arguments about the poet’s controversial politics, with Unionist pundits repeating the accusation of his support for Nazism.

MacDiarmid had pre-empted all of this. The poet who wrote hymns to Lenin in the 1930s set out his credo in A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle from 1926:

I’ll ha’e nae hauf-way hoose, but aye be whaur

Extremes meet – it’s the only way I ken

To dodge the curst conceit o’ bein’ richt

That damns the vast majority o’ men.

Paradox was central to MacDiarmid’s creative and political modus operandi: the Scots poet who turned to writing global English, the Scottish nationalist who was also a communist. When accused of contradictoriness he liked to quote Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes).

To look in MacDiarmid’s poetry – any poetry – for the ‘correct’ political attitudes is to go hopelessly astray. Prejudice, in the broadest sense of the term, is what he invites and what he seeks. MacDiarmid was, and continues to be, a lighting-conductor for prejudice in contemporary Scotland. And just as the critic Michael Wood sees violence as being fundamental to W. B. Yeats’s poetry, prejudice was a spur to MacDiarmid’s creativity.

MacDiarmid’s extremism relates in part to how he saw Scotland just after the First World War. MacDiarmid wanted to defeat the Kailyard: Scotland as parochial, couthy, Presbyterian, and pre-industrial. Scotland as represented by the comedian Harry Lauder and J. M. Barrie’s ‘Thrums’. For MacDiarmid the popular Kailyard vision of Scotland did not match the realities of industrialisation, slum poverty, and increasing Irish immigration (for the record, MacDiarmid thought Irish immigration a good thing). The Kailyard, for MacDiarmid, paralysed the Scottish imagination.

But Scotland-as-Kailyard is more than merely ‘false’ cultural representation. It is an attitude of mind that for MacDiarmid is a forerunner of the Scottish cringe. The Kailyard, as represented by the likes of Lauder, breeds cultural stereotypes enabling Scotland to be more easily controlled. The postcolonial critic Homi Bhabha makes the point that stereotyping is an integral part of colonialism: ‘An important feature of colonial discourse is its dependence on the concept of “fixity” in the ideological construction of otherness’.

Of course, historians such as Tom Devine, Michael Fry and others, have shown that Scotland was central to the business of empire. But, rather than being an English colony, MacDiarmid thought Scotland was self-suppressing. And the main agent of that self-suppression was the canny Scot, described by MacDiarmid in Scottish Eccentrics as ‘very dour, hard-headed, hard-working, tenacious people, devoted to the practical things of life and making little or no contribution to the more dazzling or debatable spheres of human genius’.

MacDiarmid countered the canny Scot – a ‘demographic’ we can imagine was targeted by indyref Project Fear strategists – with the Scottish eccentric: figures such as James Macpherson, author/discoverer of the Ossian poems, and James Hogg, whose masterpiece is Confessions of a Justified Sinner; the world’s worst poet William McGonagall; linguist and evolutionist, Lord Monboddo; author and critic Christopher North, pseudonym of John Wilson; and Elspeth Buchan, founder of religious sect the Buchanites. Often polymaths, sometimes barely sane, what these figures have in common, apart from mostly being born in the eighteenth century, is the willingness to follow their chosen paths through to an uncompromising conclusion, no matter what the odds or the opposition. This is important for MacDiarmid because of course in the eighteenth century Scotland followed a path in union with England that precipitated the canny Scot myth. These eccentrics, whatever their politics may be, are indicators of the possibility of other Scotlands and other Scottish characters that challenge the dominant stereotype.

Chris Grieve created his own Scottish eccentric when he invented ‘Hugh MacDiarmid’ in 1922, year of Eliot’s Waste Land and Joyce’s Ulysses. It is important to remember that ‘MacDiarmid’ was a fiction, similar in some ways to Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa’s multiple ‘heteronyms’ or Yeats’s Mask. For Yeats the concept of the Mask is ‘a form created by passion to unite us to ourselves’. For Pessoa the heteronyms – writers he invented with distinct personalities – were in many ways a release from the individual personality. Yeats, Pessoa and Grieve all wanted to spark nationalist literary and cultural revivals in their small, home nations. The Mask, the heteronym and the pseudonym are factors in this, enablers of creative multiplicity. MacDiarmid allowed Grieve to speak truth to power in and beyond Scotland, inspired him to write poetry, challenge embedded interests, and explore various, often mutually contradictory, positions and prejudices. If these positions are sometimes extreme – calling for a Scottish fascism in the 1920s, for instance – then that is because he saw the cultural and political position of Scotland as being in extremis.

Yeats, Pessoa and MacDiarmid are also united by the cultural and political contexts of interwar literary modernism. They were all attracted in varying degrees to fascist ideas. MacDiarmid wrote ‘Plea for a Scottish Fascism’ and ‘Programme for a Scottish Fascism’ in 1923, only months after Mussolini took power in Italy. He called for a fascism of the Left, ‘because nationalism is opposed to capitalist materialism’. He also proposed an agrarian policy: ‘the land for those who work it’. MacDiarmid cites fascism in the Twenties – ‘whether it be called Fascist or pass under any other name’ – as a means primarily to revitalise depopulated rural Scotland.

But the evidence against the accused mounts in the 1930s, during which MacDiarmid was watched by the British Security Services. His ‘The Caledonian Antisyzygy and the Gaelic Idea’ (1931-32) asks Scottish nationalists to adopt the ‘race-consciousness’ of National Socialism. Around the same time he reviewed Wyndham Lewis’s Hitler with approval. By 1940, writing to Sorley MacLean, MacDiarmid thinks the Germans − ‘appalling enough’ but ‘they cannot win’ − a lesser threat to a future communist society than ‘the French and British bourgeoisie’. In ‘On the Imminent Destruction of London, June 1940’ the poet claims to ‘hardly care’ as ‘London is threatened / With devastation from the air’.

Unionists raise MacDiarmid-as-fascist as a means to kick the SNP, a party he was expelled from in the 1930s for communism. Fascism was not unusual among European modernists, and MacDiarmid’s brand is superficial in comparison with other writers of the period such as Ezra Pound. Nonetheless, Scottish nationalists need to acknowledge the fascist component in the poet’s politics.

What is more interesting and serious about the ‘MacDiarmid’s a Nazi’ debate is what it tells us about modern Scotland and Britain. If MacDiarmid in the Thirties believed the canny Scot to be a stereotype keeping Scotland within controllable political and cultural limits, then the Scottish and British press has played its own more recent role in perpetuating insulting, dangerous and controlling ideas about the modern nationalist movement in Scotland. One such is their continued correlation between the contemporary politics of Scottish independence and interwar fascism.

A case in point is when in April 2013 Scotland on Sunday photo-shopped the swastika onto the Saltire to illustrate an article by Gavin Bowd, author of Fascist Scotland. Predictably it caused, and was designed to cause, controversy. But little of that controversy focused on how such representations reflect on national identity, both in Britain and in Germany. As Petra Rau, a German academic working in England, argues:

there is a complex relationship between ‘fascism’ and the cultural presence of the Second World War in the popular memory of Britain […], and the way in which that presence is made to serve political purposes and underpins national narratives of heritage and identity.

Unionists see a fascist MacDiarmid as their politico-cultural trump card. The Second World War and opposition to fascism serve to bind the nations of the United Kingdom in a continuing political union, as well as fixing Britain in ‘our finest hour’. Equally, such representations also freeze Germany in its darkest hour. Both Scotland and Germany, modern civic nations, are caught in historical aspic, pinned to a superannuated Britishness, and how that reflects on others, that is maintained by the British state and the fourth estate in Britain.

Hugh MacDiarmid remains a controversial figure, not only because he was not afraid to write combatively to challenge stereotypes and change Scottish culture, but because he exposes – often through his own prejudices – the prejudices upon which much cultural and political power remains premised.

*** GO HERE TO DONATE TO OUR CROWD FUNDER APPEAL AND SUPPORT US ***

References

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 2nd edn (London/New York: Routledge, 1995), p. 66.

Hugh MacDiarmid, A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, in Complete Poems, Vol. 1, ed. by Michael Grieve and W. R. Aitken (Manchester: Carcanet, 1993), p. 87.

Hugh MacDiarmid, ‘The Caledonian Antisyzygy and the Gaelic Idea’, in Selected Essays of Hugh MacDiarmid, ed. by Duncan Glen (London: Jonathan Cape, 1969), p. 62.

Hugh MacDiarmid, letter to Sorley MacLean, 5 June 1940, The Letters of Hugh MacDiarmid, ed. by Alan Bold (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1984), p. 611.

Hugh MacDiarmid, ‘Plea for a Scottish Fascism’, The Raucle Tongue, Vol. 1, ed. by Angus Calder et al. (Manchester: Carcanet, 1996).

Hugh MacDiarmid, ‘Programme for a Scottish Fascism’, Selected Prose, ed. by Alan Riach (Manchester: Carcanet, 1992), pp. 36, 37.

Hugh MacDiarmid, Scottish Eccentrics, ed. by Alan Riach (Manchester: Carcanet, 1993), p. 285.

Petra Rau, Our Nazis: Representations of Fascism in Contemporary Literature and Film (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), p. 5.

Michael Wood, Yeats and Violence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

W. B. Yeats, MSS of A Vision, in Birgit Bjersby, The Interpretation of the Cuchulain Legend in the works of W. B. Yeats (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri, 1950), p. 128.

Scott Lyall is Lecturer in Modern Literature at Edinburgh Napier University. He is author of Hugh MacDiarmid’s Poetry and Politics of Place, and editor of the recently published International Companion to Lewis Grassic Gibbon and Community in Modern Scottish Literature.

This literary machine killed Kailyard

Outlander?

Fretting about MacDiarmid’s alleged fascism is about as sensible as worrying about Jean Brodie’s enthusiasm for Mussolini. Expressions of approval for the apparent vigour and efficiency of Europe’s fascist regimes were common in the 1930s.

Benito Mussolini, received the order of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath from King George V and was referred to in 1924 issue of Who’s Who as Sir Benito Mussolini, G. C. B.

An interesting article, but the relevance of MacDiarmid is surely as an historical footnote of around 80 years ago and really hasn’t much to say about current Scottish Nationalism. I’m troubled by arguments constantly urging us to acknowledge crimes of our ancestors. They aren’t relevant unless the mindset which produced those “crimes” still exist.

And why only Scottish Nationalism. Doesn’t Churchill’s preventive war against the Soviet Union inform the Blair/Bush wars? We could go back even further and examine UK militarism.

Every SNP MP and MSP wears a white rose to honour him, at every opening of both parliaments. If it’s no longer relevant, gonnae tell them to stop?

Why?

‘MacDiarmid allowed Grieve to speak truth to power in and beyond Scotland’

Was their ever a more sinister phrase written?

Distinguishing between Communism and Fascism misses the point entirely. There is no contradiction in systemic terms, they are both sides to the same coin, hence the reason it is so easy for far left ideologues to switch to the far right and back again. See the US Trots out of which Neo Conservatism was born or the old Commi’s who are now on board with Putin. The problem is ideology, vanity, myopia, utopianism and intolerant polemic.

Both Communism and Fascism are politically modernist constructs and therefore identical in their motives their inevitable totalitarian outcomes. Both are predicated on bullshit Hegelian dialectics (the totally spurious and unempirical notion of grand narratives through history, or historical processes acting in a scientifically measured way like the theory of evolution (historicism)- Marx was a great fan of Darwin and wanted to dedicate Kapital to him just as Hitler adopted social Darwinism and eugenics).

The objection to Mcdairmid is not simply that he was a fascist, but also that he then became a Communist, thus reinforcing his dependence on Utopian/ nationalist modernist ends for political, social and cultural definition while refusing to acknowledge the processes of totalitarianism (left or right).

Apologists for Mcdairmid always rely on false comparisons to get him out of jail. They dismiss his fascism as pre-holocaust/ WW2 and therefore not ‘actually fascism’ or make the false distinction between Communism and Fascism or claim it was simply intellectual posturing – playing with modernist themes (the latter at least has some validity). However they all remain weak defences as many far sighted Liberals, Social Democrats and conservatives (of the Burkian sense – opposed to Jacobinism and contemptuous of the conceit of Robispierre) of the time (of which Mcdairmid would have been more than aware) dismissed both Communism and Fascism, seeing them for what they were, exactly the same construct, and fully understanding that they both lead to political authoritarianism and intolerance. The e.g) Keynes, Joyce (after his dalliance with the Futurists), Scott Fitzgerald, Getrude Stein, Hemingway, Orwell, Karl Popper, Hayek, Wittgenstein, Bertrand Russell, Einstein, Roosevelt, Churchill, Beveridge, Bevan, Beveridge, Picasso, Dali, Sartre, Camus, Marlena Detreicht, Berlin, Brecht, Isherwood, …in fact the list is very long. Why compare Mcdarimid’s dodgy politics with the dodgy politics of Ezra Pound or point to Knut Hamsun as ‘what aboot…’. It’s true he was hardly alone, and hardly unique in his support (or willful misunderstanding) fascism/ Communism in the 20’s and 30’s – Waugh, Shaw (were on the religious right and sometimes ambivalent as the Catholic Church was)… when the real comparison is perhaps with T S Eliot (the greatest modernist poet and despite being right wing and conservative/ religious was in fact implacably a liberal humanist when push came to shove). Pessoa, for the most part, despite initial acceptance of Salazar and the Estado Novo, was critical (cryptically) and implacably anti Hilter/ Mussolini and Bolshevism. His Cosmopolitan nationalism was closer to that of Joyce. Both ultimately ended up rejecting cultural nationalism for a pan European fluid notion of culture, unlike the Yes nats of Scotland today or Mcdairmid.

So Mcdairmid also must be judged as with other modernists, such as Auden on his willful blindness to Stalinism (a leftist fascism) and their associated apologist attitudes towards political violence. Unlike Auden, Hemingway, Laurie Lee, Keostler, Orwell and many others, Mcdairmid stayed at home during the Spanish Civil War where as they went and fought and learnt and ultimately rejected (or most did- perhaps not Auden).

Mcdairmid ‘First, Second and Third Hymn’ to Lenin is testament to this blindness and acceptance of the excesses, totalitarianism and violence of the Soviet regime. That Lenin should deal with Glasgow’s ‘public men’ by going through them with a machine gun’ And in ‘The Battle Continues’ a long sprawling poem romanticising the Republican Spanish War, while dismissing the horror and violence as a step on an inevitable ‘process’ that totally ignores the authoritarianism of the leftists that Orwell so eloquently wrote about in Homage to Catalonia and criticised in ‘Inside the Whale.’

Whether Mcdairmid was a Fascist or a Communist is mere semantics. What he is really criticised for is being anti-liberal, authoritarian and accepting of political violence for his narrow view and ends entirely predicated on dangerous notions of perpetual struggle, social evolution, grouping and defining individuals as ‘groups’ good or bad (similar to intolerant religion and political authoritarianism) intellectual snobbery and contempt for the everyday/ mundane (wasn’t a great fan of ‘the people’ thought himself above them and like all radical revolutionaries he of course knew better. And it’s always someone else that makes the sacrifices for their grand cause, never them) and contemptible historicism (the root of all totalitariansim).

Sartre side by side with Camus as an anti-totalitarian? You jest surely…they fought about it and fell out about it and Camus was shunned by the CP press and numerous French intellectuals as a result of his distrust of the Party.

And Dali was sympathetic to Franco, and even Machado, fundamentally a Republican, wrote his Ode to General Lister, and you forget to mention Heidegger, Leni Riefenstahl and god knows how many other European intellectuals in the 30’s who were either Communists or Fascists, but the majority probably.

Half of your list are Brits. Britain has a totally different intellectual tradition to the rest of Europe, and MacDiarmid was writing when the British Empire was sat its height. You’re too harsh on him, and in any case, I agree with Borges when he said that it is always a mistake to judge artists on their politics….what about the work? That’s the real way to evaluate MacDairmid, and there he is the most important artistic figure of 20th century Scotland.

Fair point about Dali – Sartre less after Hungary 56 (but was a supporter of Algerian nationalists), but not to quibble. Either way, non of this changes the central point about Macdairmid, that he still demonstrated modernist / fascist attitudes and indulged in historicism long after it was abundantly how the totalitarian process and political violence worked systemically – when most had abandoned their 20s, 30s 40s support of fascism and later Communism when it could no longer be sanctioned (that the Soviet Union was ok – the Beatles wrote a good song about it) with any reasonable degree of truth. This means it is perfectly acceptable for people to point out that he was, well… a fascist, or had fascist tendencies and for it to be perfectly legitimate for others to ask of any movement that associates/ apologises for such views/ art, as sharing those intolerant values. Deflecting and blaming those who do and lumping them as ‘Unionist’ and projecting the same criticisms to counter such criticism is pointless.

That he was a good poet is not in dispute. Neither is the bit about the UK and it’s hang up with WW2 and popular memory – need to get over it. The point is this doesn’t excuse Scottish nationalism’s narrative if it is predicated on cultural figures like Mcdairmid.

Also, the list is not exhaustive, was off the top of my head and you rightly point out many intellectuals were far left or right (ambiguous and changed their minds about things also) but many also weren’t and were implacable liberal democrats, despite other dodgy views on Empire (Churchill). which was the point. It has Americans, Russians, Spaniards, Germans, Irish, and Austrians on it and I could’ve included many others.

Fair enough, I am not in disagreement with you about MacDiarmid’s politics in general. My point is that in the context of the European intellectual tradition, there is nothing much unusual about him, and of course, installing himself in that tradition at the expense of the British tradition was part of his project, he wanted to reconnect Scotland to Europe.

He was also a man of paradoxes and contradictions: Hume was the Scot he admired more than any other. He was also a born polemicist, provocateur and shit-stirrer. “Scottish Eccentrics” is a great book by the way, written in direct retaliation to Edith Sitwell’s”English Eccentrics”, if I am not mistaken.

To wake Scotland from its slumber, he was prepared to deal in excess, and without him, our distinctive intellectual tradition would be much, much poorer.

I don’t believe in judging artists by their politics, at least not once they’re dead.

As for nationalists rooting themselves in MacDiarmid, besides a few Scottish intellectuals, I have never encountered that at all. I would be amazed if Fiona Hyslop has read MacDiarmid, and probably about 5% of the SNP rank and file could a quote a line of his poetry. The SNP wouldn’t touch him with a barge pole.

Despite all his failings, no Scottish artist I can think of has taken the cause of Scotland so seriously and shed as much light on Scottish culture, not just literature of course, but music too, say, and painting.

“The SNP wouldn’t touch home with a bargepole”? … Every SNP MP and MSP wears a white rose in his memory at every opening of both parliaments.

‘That he was a good poet is not in dispute’ I would write that all that matters about MacDiarmid is his poetry, his chosen art. Should we celebrate mediocre artists just because they were nice guys or gals ?

What evidence is there that Scottish Nationalism’s narrative is predicated on MacDiarmid and his fascist tendencies? What evidence is there of fascism in Scottish Nationalism? None, I believe. To suggest otherwise is to fall into the trap of those who think any slur, however absurd it may be, is legitimate politics.

And Churchill had more than “dodgy views”. There is good evidence that he “engineered” the Bengal Famine. “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.” There’s much in the UK cupboard, (mostly kept firmly shut) of a far worse nature than one eccentric poet’s dodgy views. Time for the Unionists to acknowledge their past?

Oh and it was George Orwell who shopped Mcdairmid to MI6. Hardly a Brit Nat apologist.

Grieve was being watched by the Security Services from 1931, long before Orwell made his ‘list’. (See Scott Lyall, ‘“The Man is a Menace”: MacDiarmid and Military Intelligence’, in Scottish Studies Review 8.1, Spring 2007, 37−52.)

(for the record, MacDiarmid thought Irish immigration a good thing).

(For the record, he also thought that famine in England would be a good thing irrespective of the innocence of those who would do the starving). Nice guy eh!

met and talked with yer man on a number of occasions. also watched him daily during the famous 1963 “Alec Douglas Home” by election in Perthshire. Chris Grieve was one of the candidates – and seemed to me to be as straight and honest as any of the others!

I also met the man, in his last summer, just before he died. He impressed me as warm, generous, and kindly. He loved Scotland and all who wished her well. No matter who they were or how little their talent. Later, in the autumn, after he had passed away, I met his friend Norman Macaig. He asked me how I had found him. I said, ‘like anybody’s kindly old grandfather’ and he replied, ‘Ah! You met the real man’.

You write as though the SNP have been disassociated from him since the 30’s and it’s unionists who keep bringing him up.

Every year, at the opening of both Holyrood and Westminster parliaments, *every SNP MP and MSP wears a white rose to honour him* .

To imagine a broad equivalent; Hugh McDairmed corresponded favourably with Mosley. Would you be so quick to look over it if every conservative MP and MSP turned up at the opening of parliament in ‘blackshirt’? I doubt it.

Ever read the poem?