Aye’s right!

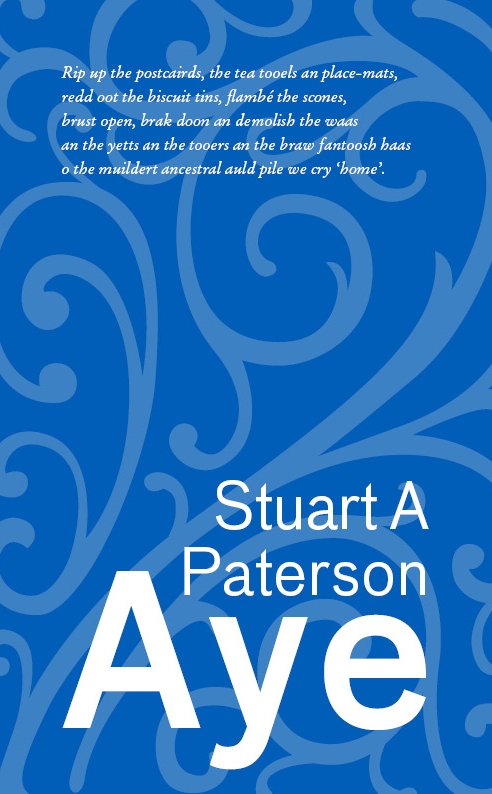

Stuart A. Paterson’s recent pamphlet, Aye, for Tapsalteerie signals a return to his native Scots, following the success of his last English-language collection, Border Lines, for Indigo dreams. The return is much lauded in the foreword by Chapman’s Joy Hendry, clearly thrilled to read the real deal, noting that Scots writing has, rightly made a resurgence, en vogue, in recent years, but has nonetheless been dogged by those who “produce poetry hovering on sentimentality, work only vestigially Scots, or an egotistical, ill-informed, self-invented mishmash that offends the ear.”

Stuart A. Paterson’s recent pamphlet, Aye, for Tapsalteerie signals a return to his native Scots, following the success of his last English-language collection, Border Lines, for Indigo dreams. The return is much lauded in the foreword by Chapman’s Joy Hendry, clearly thrilled to read the real deal, noting that Scots writing has, rightly made a resurgence, en vogue, in recent years, but has nonetheless been dogged by those who “produce poetry hovering on sentimentality, work only vestigially Scots, or an egotistical, ill-informed, self-invented mishmash that offends the ear.”

Indeed, Paterson writes from a position of authority in his native Ayrshire dialect, a language he clearly adores and feels comfortable using once more, now resident in rural Galloway. Readers expecting some sort of synthetic Scots in the vein of MacDiarmid, should beware. Though keen to promote a standard orthography for the language, and adhering closely to the norms suggested by the Dictionary of the Scots language, Paterson’s poetry in Scots as she is spoken, or indeed, as he speaks it. Two stanzas into the collection, the voice is already clear, bellowing off the page as if down a digital phone line or echoing around the empty pint-glasses of his local in Galloway.

The poetry is rich, with personal philosophies, an unrelenting sardonic humour sometimes bombastic, other times self-deprecating, which repeatedly cuts through the bullshit of post-millennial life to drop a sentiment which startles with its honestly and universality. Linguistic differences aside, Paterson, like McDiarmid before him, uses the local and the national to evoke the international and the universal, and once the language barrier is traversed, the poetry maintains a grip on the reader from cover to cover.

Structurally, the volume is telescopic in its approach which a perspective which, at times, hover far above Paterson’s world as he knows it, and at others, zooms in, incrementally, in order to for the poet to focus on his subjects at varying degrees of proximity. Thus, the new pamphlet works on various levels, ranging from the intensely personal, with the romance of ‘Dwam’, to the national, as he sets out his desires for his native Scots in ‘Leid’ with other poems, such as ‘Space’ and ‘Space-stane’, which transcend political borders, observing our dear blue planet from a quiet corner of the firmament. This modus operandi is summed up appositely in the final stanza of the title poem:

“We’re canny, no cannae, we’re aye and we’re aye,

We’re Scottish, we’re British, we’re World, we’re I.”

Indeed, ‘Aye’ opens with a call to arms, which sets the tone from the off. This is a manifesto which demands that all Scots ‘wipe off your jockodile tears’ in order to take a fresh-look at this nation, post-devolution, post-independence referendum. Indeed, within the confines of this three-page work, Paterson lattices the entirety of his nation, ranging from his home in Dumfries, to Dingwall, Dores and Dundee, alighting, bird-like, on a vast list of Scottish archetypes, stereotypes and cultural artefacts as he acknowledges their existence yet questions their relevance in the era which we now live. Yet ‘Aye’ rumbles along with a touch of uncertainty, despite navigating the cultural signposts of the Scottish landscape, where Paterson, like a bird without a coup is riddled with a sense of unease, uprooted again and again by a series of earth-tremors, predicating the imminent explosion, expressed in the final stanza.

Paterson’s Scotland, in the title poem, is set to blow, which is no bad thing in his eyes, for surely this is only way to rid herself of the bonds of parochialism and tartanry which muffle her authentic voice, ever-plural and acutely aware rich native cultural diversity. The poem lays out openly examples of Scotland’s heritage which Paterson feels to be of note and value, whilst juxtaposing his Scots Cyclopedia with a bristling critique of Scotland as commodity for export, reviling the trade of tourist trapping denoted by ‘tea tooels and place-mates’ and ‘biscuit tins’, which have so often replaced local business, whether your High Street is Princes Street, Buchanan Street, Union Street or Academy Street.

The title poem is succeeded in the volume by a bristling rebuttal of ‘No’ voters, post-referendum. Indeed, after siphoning off the angle’s share of Scotland’s excellence in the title poem, previously, Paterson, in ‘Naw’ is at a total loss in comprehending what he sees as a complete betrayal of the nation at the hands of the 54%. Indeed, the shock waves emanate internationally, with Paterson’s world gone ’heelster-gowdie, tapsalteerie’ in the post-vote hangover. His response is visceral, to mute the hypocrisy he sees in others, as he sees Scotland’s true voice is muffled in the previous work:

“Maun wheesht an sing nae sangs at aa –

they hae nae richt. They votit Naw.”

If this diptych represent is a love-song to a Scotland that could have been, and indeed, could yet be if only for a thorough shake-up, it is well placed, juxtaposed next to ‘Dwam’, which expresses some more corporal carnal desires. The love here is romantic and unrequited as Paterson observes a love interest in the arms of another. Despite the necessity, Paterson is again at a loss as to how to enact the necessary change, wishing ‘that we wur thaim’. As with the referendum, Paterson’s telescope spies a situation that could have been so very different.

Personal relationships examined in the volume range from the romantic to the social and the familial as in ‘Faither’ where Paterson examines a spectrum of parental relationships between men. The poems sees Paterson reel against the traditional family unit at the heart of society, based, in Scotland at least on the Gaelic patronymic system, where surnames are passed from fathers to sons. Paterson examines the space between the links in this chain; the realm of those step-fathers and father-figures who step up in extremis, that liminal space between the present and the past where the eyes bequest of genetics stares out of the window, bleary-eyed.

As in ‘Yuill Tide’, there is a sense of nostalgia to this poem, bolstered by the reference to tradition. A nod to Gaeldom, appears again, where with the Minch stretching out of the past and into the future, behind a vista of tourism and commercialism, the homes of once thriving island communities, who have been displaced at the hands of capitalism and the brain-drain which sees so many young Gaels seek their fortune in the big city:

“The sea will be Hebridean, B&Bs

regurgitatit hames fae the past’s

drouthie thrapple”

This once Gaelic-speaking environment is temporary haven of the holiday-maker, now, and the imagery is heightened as Paterson turns the perspective in on himself, sitting ‘bi a hairbour’, Tupperware box in hand, eating a packed lunch of Christmas dinner leftovers.

The juxtaposition of nourishment picked out of the carcass of festive cheer is stark, as Paterson’s psyche fills in the blanks of this seaside settlement, gutted out by time and community displacement, until he, like the vista he perceives is emptied out into the ether, becoming ‘a pooch full of air’, ready to be refilled, by the coming year, where back at the pub, in ‘Fou’ Paterson surveys his own mortality in the empty pint-glass:

“Hoo

the hailie hell’d it cam tae this?

Ocht aye. Acoorse. Ah’m on the piss.”

Emptiness and the need to fill the void are recurrent themes within the volume, though Paterson is clear throughout that in doing so, the selection must be carefully made. There is no sense of ‘anything will do”. And yet, it is far out amid the greatest emptiness of them all, outer space, where Paterson really allows himself to take flight.

Unfettered by the social responsibility he clearly feels towards his nation and linguistic community, personifying a meteor flying through the void of Outer Space, complete with plays-on-words alluding to Halley’s comet, Paterson is able to let his humour spread its glorious wings to their fullest capacity and it is here that the poetry truly rings with his personality. Paterson demonstrates his mastery of his craft to the highest degree here, confident enough to perceive the infinite on his own terms, through the prism of his own philosophy, which makes no space for indoctrinated theology. Indeed, in ‘Space-stane’, Paterson occupies his own liminal space, between space, itself, and time.

“A ‘meteorite’, that whit Ah am,

a cosmic kina wham-bam-slam”

Similarly, cocooned under his quilt in the dark of night, the poet’s over-active imagination again takes flight, imagining an eight-legged interloper into his downy sanctuary. ‘Ettercap’ is a hilarious romp through nocturnal paranoia and irrational arachnophobia and, again, demonstrates Paterson’s ability to make traverse the causeway between the personal and the universal.

The piece rings with oratory, heightened by unabashed use of onomatopoeia and pop-culture references. This is the Paterson of his many popularly acclaimed public readings rendered authentically on the page. Bellowing against the clamour of last orders and the back-door banging in the bitter wind as smoking social-lepers slip out for a sly fag.

In ‘Aye’ we encounter Paterson as a poet at the top of his game, who has been around long enough to have seen and known, and confident enough in a craft he has made his own, to celebrate and castigate, where necessary, with direct language which holds no prisoners. The brevity of the pamphlet leaves the reader wanting more, and will hopefully serve to propel it onto other titles in Paterson’s oeuvre. Though in another way, this brevity is a gift, and Tapsalteerie’s Duncan Lockerbie has employed certain editorial expertise in aiding Paterson, not just with the keen selection of the poets published therein but their clever placing, which imbues each work with maximum impact.

Comments (1)