The Promised Land

“The blooming appearance of this place forms a delightful contrast with the bleak aspect of the mountains within view. The traces of tillage on a spot surrounded by so much sterility, interest us like the first faint tinge of returning health on a countenance long wasted by sickness or famine.”

“The blooming appearance of this place forms a delightful contrast with the bleak aspect of the mountains within view. The traces of tillage on a spot surrounded by so much sterility, interest us like the first faint tinge of returning health on a countenance long wasted by sickness or famine.”

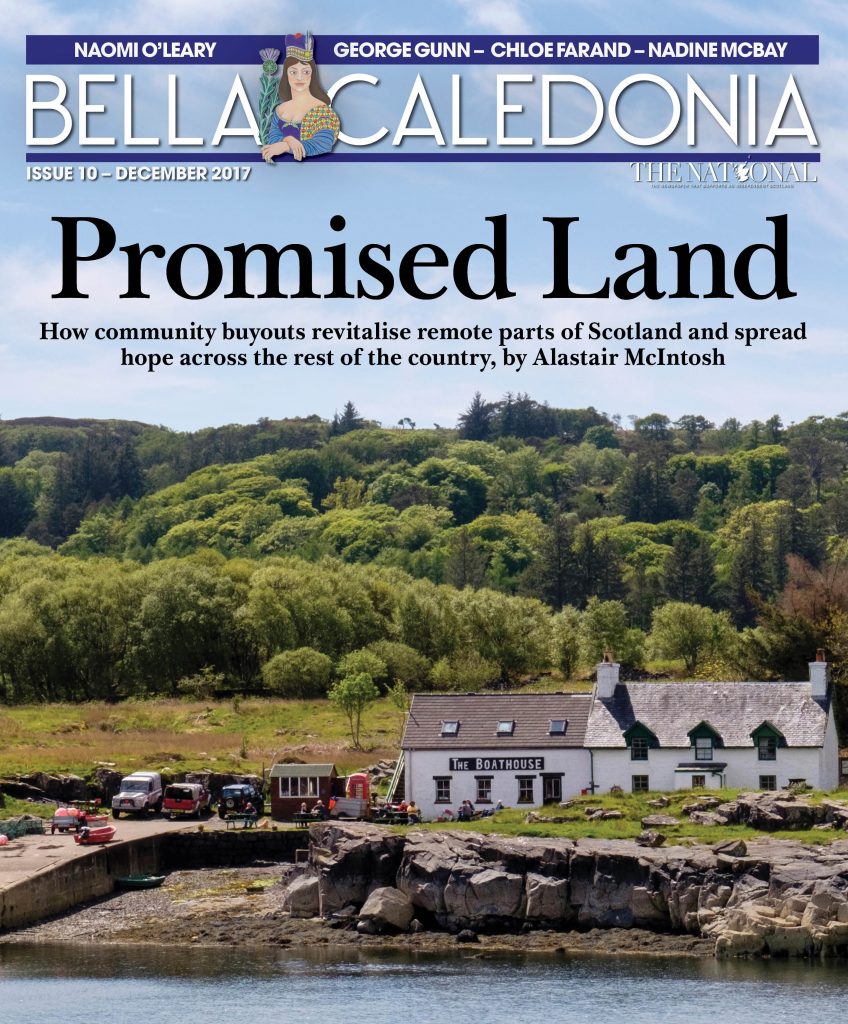

So wrote the English landscape artist William Daniell as he sketched the Isle of Mull as seen from Ulva. It was the summer of 1813. His vision of the latter, his vantage point, was bucolic.

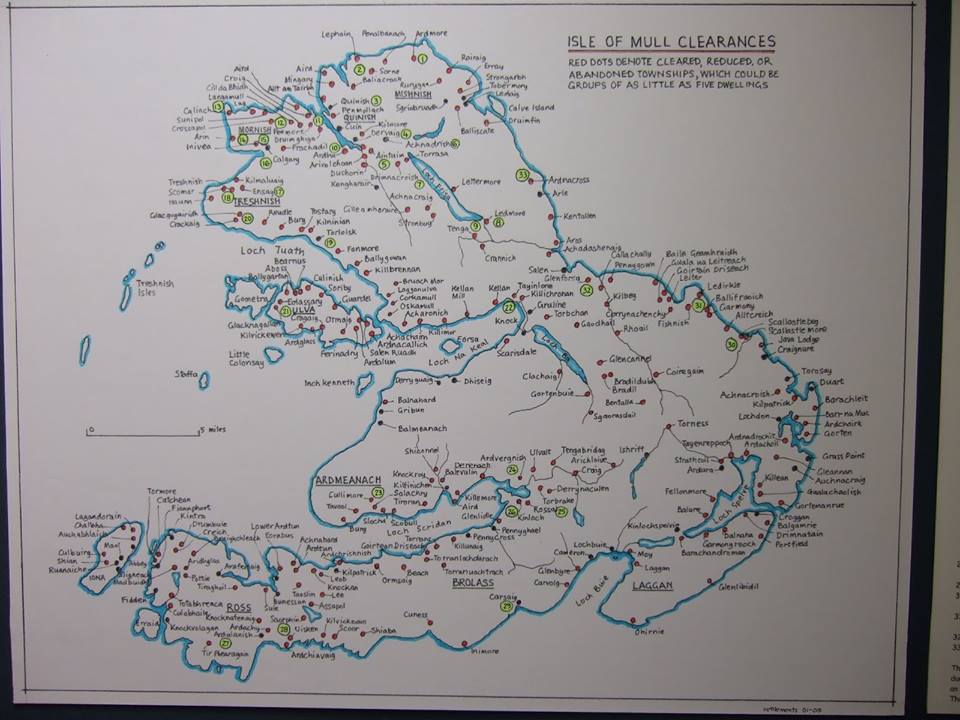

Ulva’s name is Norse. It is thought to mean the Isle of Wolves. However, it was not to be the once-native wolf that the people had to fear. The Highland Clearances would be predation of another kind. These would leave Ulva, large swathes of Mull and several other nearby Inner Hebridean islands largely emptied of their human populations, wet deserts that would linger to the present day and haunt the human soul.

Today, Ulva’s population has collapsed by 99%. It has dropped from six hundred, to just six. The island has been put onto the market. It is, said of the selling agents at Knight Frank in a comment to Business Insider UK, “without doubt the most beautiful and remarkable property I have dealt with in my career. The scenery is truly breath-taking [with] a range of property and land types…”

Quite so. This is where the grandfather of missionary explorer, David Livingstone, lived in a cave on a raised beach as he built his croft house. The Livingstone’s Cave Walk is now a tourist feature. It also draws archaeologists, who dig up the bones of Arctic fox and lemmings. Human remains also yield their testimony. Here we have a property that boasts eight thousand years of residence.

The Community’s Buy-Out Bid

But tenure of the cave, and its two thousand hectares of surroundings, may be on the verge of transformation. In October, the Scottish Government invoked the Land Reform Act to take the island off the market.

Due process has now been set in course by which Ulva’s remnant of residents and the wider nearby resident community hope to bring the island under community land tenure. Led by the North West Mull Community Woodland Company (NWMCWC), the hope is to raise funds and exercise the pre-emptive right-to-buy that the law allows. Any other bidders will have to hold off for the time being. Said Colin Morrison, Chair of NWMCWC:

“Ulva Ferry School was threatened with closure a few years ago and the resulting, ultimately successful campaign to keep it open, brought people together in the realisation that the only sure way of effecting change was by taking proactive steps to secure the future of their community. Thus the people of the area are already keenly aware of the necessity of working together for the common good. It is within this context that our plans for a buyout of Ulva sit – within a community that has already accepted its ability to shape its own destiny rather than assuming the role of bystanders.”

The laird or landlord who is selling is a generally liked Old Etonian, a onetime army captain called Jamie Howard. His asking price was offers over £4.25 million. Such horizons may or may not include a speculator’s premium as Scottish islands, on the international islands’ market, have been described as “a collector’s item”.

Under the land reform provisions the Scottish Government is conducting an “economic valuation”. Meanwhile, by postal ballot, the surrounding community on Mull will be asked whether they back the idea. If a positive result is declared on 9th January 2018 the fundraising – which has already made an encouraging start – will shift into high gear.

Giving Hope

In the free arts newspaper, ArtWork, the columnist Sir Maxwell Macleod, reported that Howard had asked him “for advice on how to evaluate whether the place could be sold into community ownership.”

I wondered what Morrison had made of that.

“It is very much to be hoped a community purchase can provide a ‘win win’ situation, for both the Howard Family and the local community,” he told me.

“We would want to see that Jamie Howard will always feel that he belongs, and is most welcome here. That’s not about ownership. It’s about fundamental human respect.”

An application to the Scottish Land Fund will be central. This currently feeds £10 million a year into communities, resourced by the reintroduction of business rates on sporting estates.

The deadline for finding the valuation price is 9th June. It sounds like Mission Impossible, but other communities including North Harris and Gigha have done it. I was on the board of the Eigg Trust at the time when £1.6 million came in from 10,000 donations. Only some £30,000 was public money. One envelope stays vividly in my mind. I watched it, amongst many similar, being opened on Maggie Fyffe’s kitchen table in 1997.

Two pound notes dropped out and a handwritten note.

“It gives me hope. From Unemployed, London.”

To us, that counted more than just two hundred pence. That was a shot of fire into the belly. It was the same at a community meal in Govan the other night. In a local news roundup, I told folks about the Ulva appeal.

We were in the kitchen, and one of our grassroots guys, John Noble, just threw his arms wide open. He was of urban stock, but his support fired up straight from the hip.

“How are we going to get the money for these people?”

There you see it. Scotland’s land reform, Mull and Ulva’s aspirations, give people hope.

Is Ulva Justified?

What, then, is the justification for what would be a major community buyout of a virtually uninhabited island, albeit one separated from Mull by just two hundred yards of shallows?

A month ago, linked to an invitation from the Iona Community, I gave some talks on Mull and at Iona Abbey.

While there, I was approached by several local residents who asked what I made of the proposed Ulva buyout. I didn’t at first have an informed answer. However, I noted that, without exception, they seemed excited by it. It had to do with reclaiming the context for community. With seeing heritage, not as a fossilised entity, but as a living force that is the antidote to hollow individualism.

Community land buyouts matter to people, not just for economic reasons – though I’ll come to those shortly. They matter because, at so many levels, they give life.

Folks like Unemployed from London, or John Noble of Govan, see that very plainly.

From Prosperity to Starvation Point

To activate a living heritage means activating history. Ulva was once the clan territory of the Macquarries. When Dr Johnson and Mr Boswell visited in 1773, they were hosted by the last of the resident Macquarrie chiefs.

He told them that his lineage went back nine hundred years. His ancestors were buried in the cemetery of saints and kings on Iona. Now, however, debts were forcing him to sell.

The same was happening all over the Highlands and Islands at the time. The Statutes of Iona (1609), the introduction of “improved”, “Sassenach” or Anglicised ways, were easing or squeezing Highland chieftains out of their customary roles. Land was less and less valued for how many souls it could support. Land was now just yet another commodity, to be bought and sold to the highest bidder.

Although Dr Johnson conflates the clan (or family) system with feudalism, he nailed the problem, the introduced shift in the political and economic base. Writing to Boswell on 22 July 1777, he took pot shot at Ulva’s new owner, remarking:

“Poor Macquarry was far from thinking that when he sold his islands he should receive nothing. For what were they sold? And what was their yearly value? The admission of money into the Highlands will soon put an end to the feudal modes of life, by making those men landlords who were not chiefs…. Every eye must look with pain on a Campbell turning the Macquarries at will out of their sedes avitae, their hereditary island.”

The Macquarries scattered – whether to their deaths at Waterloo, or, as with Major General Lachlan Macquarie, to become “the father of Australia.”

Around Boswell and Johnson’s time the island had supported at least one fishing boat for every family. Its eight square miles had exported a crop of potatoes. In the years following their visit the mainstay of the economy became kelp. Kelp is seaweed that has been burnt in kilns to manufacture industrial chemicals. The industry brought hard and filthy graft to the people but for landlords, prosperity.

As such, it was a bucolic scene that William Daniell sketched from close to Ulva House in 1813. By now, it was the country residence of Sir Reginald Macdonald Steuart-Seton, Second Baronet and Sherriff of Stirling. Notwithstanding what Daniell spoke of as the “many prejudices” and “desponding expostulations” getting in Macdonald’s way, his “agricultural improvements” had resulted in:

“… a garden which, by the variety and richness of its products, might vie with those of a more favoured clime, and which proves that even in the Hebrides the vows paid to Flora are not ungraciously requited.”

Come 1835, and three years before his death Macdonald sold Ulva on to a certain Francis William Clark. He was a lawyer from Stirling, originally from Morayshire, and by this time Ulva’s population stood at around 600, spread across sixteen townships.

By now the kelp industry was finished. However, it had left behind a community of carpenters, boat-builders, cobblers, subsistence farmers and fisherfolk but a weakness had entered the island’s ecology. Seaweed burnt and exported as kelp meant seaweed not put on the land each year to keep its ancient fertility intact. Notwithstanding Macdonald’s impressive “garden”, both the soil’s condition and smallholder agricultural skills had declined.

As happened over much of the Highlands and Islands, a diversity of crops that included oats and barley had narrowed to a dangerous over-reliance on potatoes. When the blight fungus struck in the late 1840s the people, like those affected by the Irish famine, were left without sufficient fallback.

At first Clark provided some relief. However, he was not a man of peasant sympathies. In The Making of the Crofting Community James Hunter records how he took, in the words of one of his admirers, “a decided stand against crofting”. By setting fire to the thatch of their humble cottages, he proceeded to convert crofting arable land into grazings. Over a mere four to five years his waves of evictions of the peasantry collapsed the population from its 600, to just 150.

Those left behind either drifted away more gradually, worked in waged labour for the laird, got whittled away in later evictions, or got pushed over to a human dumping ground at a spot called Aird Glas.

The National Library of Scotland hosts a website made by local school children. It includes a map with a walking tour. A link to Google Earth clearly picks out terraced ruins and other homesteads visible to satellites in space. The children write:

“Aird Glass was always a last resort because life there was so miserably desolate. Most of the people who went to Aird Glass starved because it was too boggy to grow crops. That’s why its known as Starvation Point.”

The urban unemployed of today – our London or our Govan friend – are very often caught up with the consequence of intergenerational poverty from such times as this. That’s why, although they may be urban, they draw hope from rural land reform.

Hope, for What?

Jamie Howard has farmed Ulva for some thirty years. It was inherited from his mother, the Hon Mrs Jean Howard, who in turn inherited it from her mother, Lady Congleton. She bought it in 1946 for just £10,000.

Howard did what he could as a private individual to make the island a going concern. However, the twists and turns of the community buyout bid has not been a comfortable ride. The Times profiled him on 4th November. It describes how one of his estate agents, Bell Ingram, is incredulous to see “the North West Mull community group being guided through the legislation by civil servants at every step.”

Well, the poor might have no lawyers, but they have a government.

One can understand why Howard might be ambivalent. A sale at economic valuation might lack the cutting edge of speculative competitive bidding. He told The Times:

“I don’t want to give the impression that I’m against community buyouts. At the end of the day what I want is what’s best for Ulva. But my suspicion is that all along ministers have felt that this community bid would make a good headline for the SNP conference and have given it all the help they could.”

Online comments by the newspaper’s readers dismiss the buyout aspirations as “the zealotry of the SNP and its Communist inclinations.” It is a project that “sounds more like Russia than the Highlands.” In short, “eat your heart out Mugabe,” because this panders to “core voters of the unemployed and the unemployable.”

That’s one set of views. Another, is that the NWMCWC have set their aspirations as:

“[To] manage the estate to provide sustainable benefits for the community in the short to medium term and in the long term for future generations including the repopulation of the island. Sustainable community benefit is dependent on more people living and working year round on the island itself and the way to achieve this is for the land to be owned and managed by the community.”

Community buyouts elsewhere suggest that there are four main driving forces that help land reform to be successful. These are:

- Social housing with secure tenure and housing plots can be created at low cost. This eases worry and economic pressures on young families, leading to benefits that are monetary, that affect child welfare, and are conducive to improved mental health.

- Business units and business opportunities can be set free, stimulating entrepreneurial initiative.

- Agricultural potential, ecological potential, sporting assets and renewable energy can be harnessed for the common good. For example, Eigg now gets 90% of its electricity from a local hydro, wind and solar grid, with only 10% of diesel backup. This reduces the carbon footprint of rural lifeways.

- There are a range of psychological, creative and spiritual benefits. Community structures – when well held and with support from groups like Community Land Scotland – create contexts where people grow. This includes learning how to recognise and process conflict. It includes learning, or relearning, how to take responsibility for both self and neighbours. It is from such qualities that nations grow in strength and gentleness.

Hope, for what, is hope for a better way of being human in the world. On Eigg, where all the island directors of the Heritage Trust were children at the time of the buyout, this is seen very clearly by the younger generation – a generation that are returning, and having babies.

Hope, for Ulva

Ulva is an opportunity to renew community and to stimulate the same in surrounding areas of Mull with a clean sheet of paper. With the population down to just 1% of what it was, there’s a remnant taproot of community, but the chance for new beginnings.

The NWMCWC has proven experience of running a multi-million pound economic venture. If anybody can bring an island back to life theirs is the kind of expertise that can pull it off. Said Ulva resident, Rhuri Munro:

“Having grown up here, and now bringing up my own children on Ulva, the future of the island is more important to me than ever. Too often, the people who live and work in a place have the least say in what happens there, particularly on private land like here on the west coast.

“Community ownership is not without its challenges, but ultimately it offers us a voice and an input which is not existent at the moment. I believe the interests of Ulva and the wider community are far better served by those of us living here, who have a real stake in this community, and want to see the island thrive.”

I was filming with the BBC on North Harris recently. The hotel receptionist was in her mid thirties. “How is it since the buyout?” I asked, she not knowing why I might be interested.

“Oh, it’s wonderful,” she said. “People my age are coming back. We’ve now got jobs here.”

That, too, is why Ulva is chance to be seized. The right local spirit is in place. As they said on Eigg when the fundraising began in earnest, “Let’s crack it.”

May the wind be at the back of the folk of Ulva in their effort to gain community ownership of the ground they work and stand on . Last week the recently formed Scottish Land Commission held a reception in Glasgow in the very City Hall that Henry George , more than a century before, made the impassioned case for a land value tax which would have replaced other forms of taxation . I was encouraged to hear that the new commission is mandated to revisit George’s proposals . Does land value tax threaten the viability of community buyouts ?

I’ve just seen your question, 6 months down the line. My personal view is that land value tax (or whatever of various names it might be called) should be exempt, or at a reduced rate, for land that is held in ways that are demonstrably for the public benefit and with public accountability, such as community land trusts.

Just for the record, the community buyout of Ulva was completed and celebrated on 21 June. Every good wish to them. https://www.scotsman.com/news/environment/tiny-island-of-ulva-officially-transferred-to-community-ownership-1-4758496