Representation and Storytelling: arts for social change

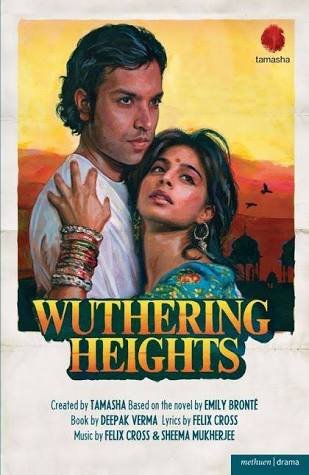

When I was younger, I remember seeing a flyer for a theatre company Tamasha, advertising their upcoming production of Wuthering Heights at the West Yorkshire Playhouse. The flyer had a distinct Gone With the Wind feel to it; the lovers in the picture holding on to each other dramatically, the sun setting in the background, with the tagline above reading: Bronte Goes to Bollywood. You see, Cathy and Heathcliff in this adaption, were Asian.

When I was younger, I remember seeing a flyer for a theatre company Tamasha, advertising their upcoming production of Wuthering Heights at the West Yorkshire Playhouse. The flyer had a distinct Gone With the Wind feel to it; the lovers in the picture holding on to each other dramatically, the sun setting in the background, with the tagline above reading: Bronte Goes to Bollywood. You see, Cathy and Heathcliff in this adaption, were Asian.

I still have the flyer now, I kept it since a teenager and have framed it in my house. Perhaps the reason I’ve kept it – and the reason it resonates so much – was because it was the first time I saw something cross over from one of my cultural frames of reference (Bollywood) into the other (Literature, Theatre and the Arts in Britain). The Yorkshire part of me (thanks mum!) and the African Indian part of me (cheers, Dad!) were both represented in this poster, and not only represented but it looked right, and exciting, like something I wanted to go see. It signalled to me that there was much more space in the arts and literature for people from wider communities than the traditional establishment, than what I’d previously been given to realise.

This ethos is something I carry now into my work as a creative practitioner in Scotland. It is no accident that whenever I deliver a creative writing workshop, regardless of the audience, the poets whose work I feature are women of colour, women writing in non-traditional ways, as well as film poetry and poems not in English. Indeed, for some of the poets I feature – Rupi Kaur being a good example – their work has drawn great critique from the literary establishment; some of it founded in genuine literary engagement, others reeking of ingrained imperialism, racism and misogyny. My reading lists are made up of writers like Ijeoma Umebinyuo, writing in less than 10 lines about the profound journey of healing, or Andrea Gibson – a white, gender-queer poet whose work touches on gender, identity, mental health, and sexual violence to name just a few themes. Poets like these were never taught on my school curriculum, their true to life topics, every-day language and spoken word never appearing alongside Shakespeare and (my beloved) Bronte.

But what if they had been?

When you teach a class on poetry, and the poets featured are in some way defying conventions of what we are traditionally taught poetry is, then this opens up to students an understanding of where their work can go and what they can do as artists. It paves the way for them to move towards their own independence and self-definition as artists. You are literally unblocking creative inspiration, taking away the sense of stigma or perception of a rule book which says you can’t do something a particular way. Further, if in our mainstream education system, we read a broader range of work by people from communities outside of the mainstream majority – whether it be in Scotland or the wider UK – as well as offering Scottish literature to be as equally Leila Aboulela as it is Robert Louis Stevenson, it may in turn impact how people from minority or marginalised communities experience a sense of place, belonging and aspiration. Importantly, it may also influence how people from majority groups treat people from other communities around them.

In the past, I have worked to teach young women of colour about the history and achievements of women of colour in the UK and globally; shared the impact of South Asian women on UK Trade Union History in the Grunwick Dispute, or of the influential suffragette Sophia Duleep Singh. In doing so, what I found was that sharing the stories of these women – who looked like my young audience, and like them too faced sexism and racism and wider discrimination – was like giving the young women permission to unlock their own voices, ambitions, pride and sense of self. Further, in reflections with the young women about the political impact of learning (or not learning) about the achievements of women of colour, we made a connection between the value placed on the achievements, success and struggles of our ancestors in the national consciousness, and the value placed on us – in the prejudice and discrimination we experience in an everyday context and the media – now.

The process of moving towards a freer way of writing is, similarly, often also a process of decolonising and deconstructing the weight of structural oppressions around us; indeed, the aforementioned writer’s ‘rule book’ has likely grown from these structural oppressions in the first instance. When we say poetry can be written in verbatim, in your local dialect, in your own combination of English and Urdu, and use examples of poets spanning a wide range of ethnic groups and social structures, we’re also deconstructing the often patriarchal, racist and classist imperialism which hangs over literature and the arts.

In my own work, it’s felt important to push past conventional notions of what I am supposed to write about. My poem and accompanying film-poem ‘Hopscotch’ is a good example of this. Made up of the words and phrases which men have shouted at me on the street, ‘Hopscotch’ takes the things which we as women and people of colour are told not to talk about, ignore, or take as a compliment, and instead holds them up like a mirror to the audience, illustrating their collective violence. The poem discusses racist, sexist and Isalmophobic harassment, and taken literally, the title ‘Hopscotch’ evokes hopping in and out of being accepted as Scottish. Taken metaphorically, it suggests the childhood game of jumping in and out of chalk lines to illustrate what it can feel like for a woman trying to navigate through harassment. Writing the poem, I recognised that, like so many other women, people of colour, and LGBTQI folk, I was walking around carrying on my back the weight of the words men had said to me on the street, with nowhere for them to go. Further, the experience of street harassment can be a very voiceless one; it’s not always easy to ‘holler back’ when you are shocked, scared, outnumbered, tired, anxious, or indeed when your assailants are shouting the abuse from a moving car. ‘Hopscotch’ was my way to not only reclaim my power and voice within a voiceless experience, but to also take that experience and – through art – use it as a tool for change.

Art, met with lived experience, is an essential root for activism to come from; it blends the personal with the political, the emotional heart with the strategic head. Indeed, storytelling lies both at the heart of the arts, and at the heart of social justice movements. And to create social justice change – whether in Scotland, across the UK, or globally – then we need to be creating space for, and supporting people from, communities wider than our own to tell their own stories in their own ways, and on their own terms.

One of my favourite workshop activities that I deliver involves participants making a ‘self-portrait’ from their words or art which draws together all aspects of their identity. I include prompts such as art by Hate Copy aka Maria Qamar, whose ‘Trust No Auntie’ merges the traditional cultural reference (aka. the ‘in joke’) about the all-seeing, all-hearing network of Aunties, with the popular Netflix series’ Orange is the New Black’s statement ‘Trust No Bitch’. All done in a distinctive, Pop-Art style. Hate Copy’s work is easier to find on Instagram than in national galleries, and it is precisely for this that I choose to use it; to consciously continue to deconstruct both the physical and social barriers to traditional arts spaces, and the traditional understanding of what art is.

It is important, when coming from a place of writing our self, of exploring our place and our community’s place in the arts, to acknowledge the whole medley of what it means to be in that community, and to be true to yourself – and artists like Hate Copy show this. Whether it’s Bronte and Bollywood, or a Masala Dosa with an Irn Bru, the more we are apologetically true to ourselves in our art, the more we challenge the notion of the single, stereotypical story held in the minds of those who may seek to misunderstand us. The more we say to those like us: come, there is space for you here.

*

Nadine Aisha Jassat is the author of Still, a feminist poetry pamphlet. She has performed solo shows at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the Just Festival, and the Audacious Women Festival, as well as speaking at Edinburgh International Book Festival, Aye Write, and Glasgow Women’s Library’s Festival of Women Writers. She was the debut writer in residence for YWCA Scotland – The Young Women’s Movement, and features in 404 Ink’s acclaimed anthology Nasty Women. Her work has been published both online and in print, including in the Dangerous Women Project and New Writing Scotland. Her piece ‘Hopscotch’ was made into a film-poem by award-winning filmmaker Roxana Vilk, and was part of the official selection for the Women of the Lens Film Festival 2017. Nadine was recently named as one of thirty inspiring young women under thirty in Scotland.

Nadine Aisha Jassat is the author of Still, a feminist poetry pamphlet. She has performed solo shows at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the Just Festival, and the Audacious Women Festival, as well as speaking at Edinburgh International Book Festival, Aye Write, and Glasgow Women’s Library’s Festival of Women Writers. She was the debut writer in residence for YWCA Scotland – The Young Women’s Movement, and features in 404 Ink’s acclaimed anthology Nasty Women. Her work has been published both online and in print, including in the Dangerous Women Project and New Writing Scotland. Her piece ‘Hopscotch’ was made into a film-poem by award-winning filmmaker Roxana Vilk, and was part of the official selection for the Women of the Lens Film Festival 2017. Nadine was recently named as one of thirty inspiring young women under thirty in Scotland.

There are more ways to introduce poetry these days. For instance, there’s a computer game called Epistory where text plays an integral part. Poetic descriptions appear (and are read out) as you explore the landscape:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistory

Maybe that format would appeal to some students.

If poetry typically uses shorthand communication that relies on cultural references and shared experiences, is there now almost a globally-shared reservoir of cultural meaning? Or is this an illusion? I seem to remember the poetry (even in Scots) that I learnt at school drew on a lot of classical Greek and Roman myths, and our curriculum included Classical Studies which primed us, I guess.