Is Scotland not ready for green burials?

If the latest statistics are anything to go by, this New Year will have been the last for almost 57,000 of us.

If the latest statistics are anything to go by, this New Year will have been the last for almost 57,000 of us.

It may not be a merry thought, but in 2016 a total of 56,728 deaths were registered in Scotland.

The number was the second highest since 2005 and there are also more of us living north of the Border than ever before, with the headcount hitting a record 5.4million during 2015. Analysts at National Records of Scotland predict this will hit 5.69m in 2041, by which time the number of deaths per year is expected to outstrip births by more than 10,000.

That more of us are living and dying in Scotland poses challenges on many fronts, including the availability of housing and the provision of health and social care.

It also raises questions about where we go after we die – from a very literal standpoint.

According to predictions made ten years ago, the answer for many of us should be neither municipal cemeteries nor local crematoria, but natural burial grounds.

Those spending eternity in the sites, which are set in woodlands, parklands and meadows, are buried in biodegradable coffins or shrouds to minimise impact on the environment. This low-impact ethos often extends to a non-embalming rule to prevent the escape of harmful chemicals into the soil, and can include a prohibition on traditional headstones. However, with no overarching framework on what natural burial truly means, these policies can vary from site to site.

What all do share is the promise of long-term protections for green land as their special status prevents development for housing or other use.

In an interview in The Herald in 2007, Ian Wells of Monmouth-based woodland burial site firm Native Woodland predicted that all Scots would have the option of a green burial within five years as more sites opened in response to anticipated consumer demand.

At the time only seven such centres had opened, and Native Woodland operated three of them – Hundy Mundy in the Borders, Cothiemuir Hill in Aberdeenshire and Delliefure in the Cairngorms National Park.

At the dawn of 2018, the growth predicted has failed to materialise even in the most populated parts of the country. Craufurdland at Fenwick, East Ayrshire, remains the closest to Glasgow despite the 20 mile distance, and even Wells’ own firm has opened no other locations.

Though there is no central database of the country’s natural burial grounds, Rosie Inman-Cook, manager of the Natural Death Centre charity and Association of Natural Burial Grounds, acknowledges that take-up in Scotland has been slower than that of England, which is home to most of the UK’s 270 such sites.

She says the funeral industry itself is to blame, claiming funeral directors prefer to promote standard options to customers as travel time to the rural sites hits productivity and profit. However, she points to a newly approved site in Angus as proof that demand continues.

Councillors voted through the application for Cairnbrae Natural Burial Ground in November, where around 20 burials per year will take place, with the scattering of ashes also allowed.

Dom Maguire, chairman of Anderson Maguire Funeral Directors, disputes Inman-Cook’s argument, suggesting instead that what is offered by a green burial is not yet palatable to most Scots.

Maguire, whose Glasgow-based family firm handles “four figures” of funerals a year, agrees the distance from towns and cities to the rural locations is a barrier to some, but says culture is a bigger roadblock.

“People are going for a half-way house,” he said, “by having a wicker coffin as what they consider being a contribution to the environment, but the concept of their loves one being buried somewhere where they deny the option of to memorialise them with a marker or headstone is something they are not comfortable with.

“I don’t think in Scotland they have made that cultural change yet. They want to have somewhere they can go and pay their respects.”

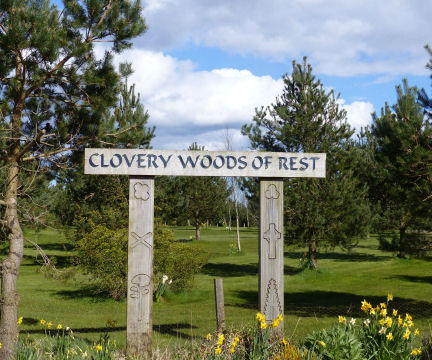

However, Fiona Rankin, who founded Clovery Woods of Rest at Fyvie in Aberdeenshire with husband Alexander, says her site – one of the oldest in Scotland – is built on respect for both the land and the individual.

The couple were already living next door to the land when Alexander had a heart attack in 2000. The experience prompted the pair to evaluate their end of life plans, eventually leading to the opening of the woods of rest two years later.

When Alexander died in 2014 he was buried there in a ceremony that included a Burns reading by his daughter and music by The Beatles.

“Neither of us fancied cremation or going in a churchyard,” she said. “We are all about choice here. Most of our burials are not religious, but we have had families come without even a humanist and just do it themselves. We have had some who have come and just stood at the graveside not saying anything, because that was what was comfortable for them.”

Rankin says her site is too far from Aberdeen for some, but says the failure to keep pace with England may be “something to do with the Scottish psyche”.

“People can be slow to take on new ideas”, she said. “People spend so much on funerals and they think they have to have the big limo – they don’t. You can come here on the back of a trailer pulled by a tractor in a plain box or wrapped in a blanket. You don’t have to have a coffin, it’s all tradition. That’s understandable, but there are people ready to break with that.”

Kirsteen Paterson is a reporter for The National with an interest in the environment, social justice, marginalised voices and the way we live now. @kapaterson

I can’t help but feel that there is something a bit imperialist about laying claim to a plot of land for all eternity. Maybe the most environmental option is to support communal reclamation plants like Resyk in Judge Dredd’s Mega City One:

http://judgedredd.wikia.com/wiki/Resyk