Nothing Exceptional: Scottish Housing Associations and the Erasure of Scottish Social Housing

After years of preferential funding allocation treatment over public housing—which has more or less been frozen out of the equation—HAs have been subject to significant reductions of state funding, making them ever more dependent on the private market.

Increasingly acting as large corporate organisations—including strong tendencies towards mergers, and a reliance on risk-laden bond funding and real estate investment trusts (REITs)—HAs now typically produce homes for market rent, market sale, so-called ‘affordable rent’ (80% of market rent in England), and home ownership—rather than genuine affordable ‘social rent’.

Those defending HAs claim that they are charitable bodies following a ‘community ownership’ model with social obligations. As I will show, this claim is untenable; but even if it were not, with massively reduced state funding HAs must submit to the prerogatives of the banks and the laws of competition in the housing market rather than the needs of tenants. The question is material and political rather than moral, and the figures are damning.

In England, only 8.4% of HA housing completions during Q2 of 2017–2018 were for ‘social rent’; the rest were for market or intermediate rent or sale. In the financial year, 2016–2017, fewer homes for social rent were built with government funding than in any other year on record, with completions down by 96% in seven years. At the same time, UK HAs posted record operating profits for the year 2017, propped up by ever-increasing debt levels which rose by an aggregate of 17% from 2016 to 2017.

The Scottish Government has garnered praise in some quarters for adopting more progressive housing policies than the rest of the UK, not least from the Scottish Government itself. They cite the nationwide cessation of Right to Buy (RTB) on 1 August 2016, the mitigation of tenant rent burdens associated with the ‘Bedroom Tax’ via state funded Discretionary Housing Payments (though not the repeal of the policy itself), and relatively progressive homelessness legislation (though the rough sleeping homeless population has never been more visible).

These measures undoubtedly have a tangible beneficial impact for tenants in an otherwise punitive housing market. Yet praise of ‘Scottish exceptionalism’ should not blind us to the extent of housing privatisation in Scotland, the enormous scale of ongoing demolition programmes, and the lack of political will for a genuine and necessary expansion of public/social housing.

Neither should it obscure current Scottish housing policies such as Help to Buy or the Rental Income Guarantee Scheme (RIGS), the latter of which not only entrenches an already over-heated and insecure private rented sector (PRS), but does so by guaranteeing the income of ‘Build to Rent’ PRS developers against void risk and non-payment of rent risk. This subsidy for private developers, a creature of Scottish government policy, it hardly needs saying, epitomises everything that is wrong with current housing policy in Scotland from a tenant perspective.

In what follows, I briefly discuss the housing context in Scotland before honing in on Glasgow, and particularly Glasgow Housing Association (GHA), which was the beneficiary of the largest housing ‘stock transfer’ project in the UK in 2003, and the largest ‘modernisation’ (read ‘privatisation’) project in Europe at the time. The consequences of this process are now all too evident in a housing landscape dominated by rapidly escalating private rent, the absolute erasure of public housing in Glasgow, and a massive overall decrease in social housing.

In conclusion, I contend that HAs are increasingly part of the problem and not the solution to the ongoing housing crisis. The independent tenant’s movement in Glasgow and Scotland more generally has been badly marginalised, in large part through tenant incorporation into toothless HA management committee structures. I argue here that its resuscitation must necessarily be central to any solution to the contemporary housing question. Living Rent Tenants Union provide one important example of how that process is already emerging.

The Privatisation of Scottish Social Housing

Like elsewhere in the UK, and indeed Europe, there has been a marked shift from the social housing sector towards private homeownership and the private rented sector (PRS) in Scotland. According to the Scottish Government, owner occupation doubled from around 30% in 1969 to around 61% in 2016. In the same period, the percentage of households in the social rented sector halved from around 50% of households to around 23%, while the proportion of households in the PRS decreased from around 20% to 5% by 1999, before rising again to around 15% in 2016. The decline and rise of the PRS, it can be noted, is inextricably and inversely bound up with the rise and decline of public housing.

The rise of the PRS, in Scotland as elsewhere, can also be attributed to the demise of the ‘homeownership dream’ as house prices have increasingly risen beyond the means of first-time buyers, creating an additional context for the consolidation of an exploited and impoverished ‘generation rent’.

The principle reasons behind the overall reduction of public housing in Scotland and the UK were Right to Buy (RTB) sales, housing ‘stock transfer’ from council housing to HAs, and massive funding cuts in the social housing sector. These can be seen as part of a wider ideological attack on the very principle of public housing, working alongside the visceral return of a usurious rentier economy and a general tendency of capital to seek profits from urbanisation rather than industrialisation.

RTB has been responsible for the loss of around 2.7 million public homes in the UK since 1980, with around half a million council homes lost to private sale in Scotland before the cessation of RTB for new applicants on July 31, 2016. Annual RTB sales in Scotland peaked at 40,000 in 1989, settling at around 15,000 between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, before dipping to 1,735 in the year ending March 2016. This means that most of the damage was done before RTB sales were closed for council housing, but that the new legislation has not been insignificant.

‘Stock transfer’ from public housing to HAs has contributed to the loss of around 1.5 million public homes in the UK since its inception in 1988. Scotland followed the policy later. In 2003, three councils undertook stock transfer to HAs (Dumfries and Galloway, Glasgow and Scottish Borders), resulting in a loss of over 20% of the total Scottish public housing stock. Another 4% was lost through stock transfers in Argyll & Bute and the Outer Hebrides in 2006, and in Inverclyde in 2007. As I will show shortly, further substantial losses to public housing were only prevented by significant tenant anti-stock-transfer campaigns in several major cities and towns across Scotland.

Following the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, housing budgets in the UK were cut by nearly 50% for the period between 2011 and 2015. Likewise, there were very significant funding cuts for social housing in Scotland. Between 2007 and 2013, the Scottish Government’s new build social housing budget allocation per house was reduced from £77,000 to £44,000.

Paul Martin, the Labour MSP for Glasgow Provan, said in a Meeting of Parliament at the time, that these cuts were ‘putting at risk the very existence of the community-based housing association movement’. The term ‘community-based housing association movement’, is something of a misnomer as I will show, but Martin’s contention that HAs are becoming increasingly precarious is entirely credible give current trends.

Scotland has traditionally had the highest level of public housing in the UK, but as Eric Clark, a prominent gentrification scholar, has argued in the context of Sweden, it is precisely because such a large public fund of institutionalised commons existed in Sweden that it has liberalised faster than any other Western country over the last two decades. A similar argument could be made about Scotland, and in particular Glasgow, where Labour Party hegemony was rapidly transformed into viral neoliberalism from the 1980s with the Labour-dominated District Council becoming an increasingly active state player in urban accumulation strategies. Glasgow’s wholesale housing stock transfer in 2003 provides a compelling case study in this regard.

In 1981, nearly 55% of the Scottish population lived in state funded council housing, and in Glasgow the figure was as high as 61%. Aside from Birmingham, the city maintained (or under-maintained) the highest percentage of public housing in the UK. Since the early 1980s, however, the tenure switch in Glasgow has been dramatic, with social rented housing (inclusive of public housing and RSLs) decreasing from 70% to 36% of citywide housing provision overall between 1975 and 2015, and the PRS, widely acknowledged as the worst of all possible tenures, increasing from 5% to 20%, and more than doubling in the last decade alone.

In Glasgow, as noted previously, the entire public housing stock of the city (81,000 homes) was transferred to GHA in 2003, making it Scotland’s biggest social landlord.

Before detailing the consequences of this transfer, it is important to note that the ballot on stock transfer was only narrowly won after a significant citywide anti-stock-transfer campaign. There was a sense that if Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland, said yes to transfer, then other Scottish local authorities would follow. But the critical understanding developed through the Glasgow ‘No’ campaign, alongside negative news of tenants’ experiences post-transfer in England, helped mobilise successful tenant campaigns against stock transfer proposals in Dundee and Aberdeen, and full stock transfer ballots in Edinburgh, Stirling, the Highlands, and more recently, East Renfrewshire and West Dunbartonshire.

In part this was down to a less complicated privatisation processes in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK. There were no Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs), and no Arm’s Length Management Organisations (ALMOs) in Scotland, meaning that tenant organisation could be mobilised around stock transfer ballots with more clarity. In part, it was because local campaigns were well organised, sometimes with the support of Defend Council Housing (DCH) and trade unions, albeit with limited resources, and in part because tenants simply did not believe their housing experience would be improved through stock transfer.

At the same time the ‘No’ votes were of note because tenants were given an extremely skewed ‘choice’ in the ballot (‘ultimatum’ is a more appropriate word), which gave no incentive at all for a vote against transfer. By contrast, the ‘Yes’ vote, in Glasgow for instance, promised total housing debt relief for the local authority from the Scottish Executive and British Treasury of around £900 million pounds; an expected demolition programme of around 11,000 council homes; and significant investment in re-cladding and maintenance (exterior and interior). There was also much talk of tenant participation and ‘community ownership’, which I will address shortly.

Since the ‘Yes’ vote, GHA has become part of the Wheatley Group, which comprises six HAs; two care organisations; three commercial subsidiaries (including Wheatley Lowther Homes, ‘one of Scotland’s leading developers, letting agents and property-management specialists’); a charitable trust; and joint ownership of City Building (Glasgow) with Glasgow City Council (GCC), a repairs and maintenance company controversially calved off as an arms-length external organisation (ALEO) from the GCC building services department in 2006.

The Wheatley Group disingenuously takes its name from the socialist, John Wheatley, the famous ‘Red Clydesider’ who was prominent in Glasgow’s 1915 Rent Strikes and who delivered the Housing (Financial Provisions) Act 1924 (‘The Wheatley Act’), which significantly increased government subsidies for local authorities to build public housing. Recuperating Wheatley’s name, it need hardly be said, is a barefaced negation of socialist principles (ideally at least), since the Wheatley Group, and its ‘family members’, especially GHA, have helped significantly privatise the social housing landscape.

Since stock transfer in 2003, the stock of GHA ‘affordable homes’ has decreased from 81,000 homes to 39,272 homes. Around 20,000 of this reduction is down to a mass high-rise demolition programme, which has provided a lucrative process for the demolition industry as well as condemning thousands of tenants to a usurious and deeply insecure private housing market. It is unclear whether ‘affordable homes’ means homes for actual social rent, but given the broad definition usually applied, the figure for genuine social rent could be much lower.

Another 20,000 or so have been ‘second-stage transferred’ to smaller Local Housing Organisations (LHOs), who now own as well as manage the former GHA properties. This was a central part of the ‘community ownership’ mantra in the initial stock transfer proposals, but has been extremely controversial since second-stage transfers have been partial and heavily delayed. As Kim McKee has observed there was insufficient pre-planning for the process and it would appear that hyperbolic claims over the process were made to convince tenants about the merits of transfer without examining the practical difficulties involved with anywhere near enough due diligence. Ultimately, the basic and eminently foreseeable problem is one of cost, with GHA and LHOs haggling over the price of acquisition.

Transforming Communities Glasgow?

A closer focus on one particular GHA joint initiative reveals a striking recent housing privatisation plan via eight area-based regeneration programmes. The Transforming Communities: Glasgow (TCG) programme, formerly the Transformational Regeneration Area (TRA) programme, is led by the GHA, Glasgow City Council (GCC) and the Scottish Government. Initiated in 2007, it covers eight different areas of the city–East Govan/Ibrox, Gallowgate, Laurieston, Maryhill, North Toryglen, Pollokshaws, Red Road/Barmulloch and Sighthill–with the latter claimed to be the largest urban regeneration project in the UK outside of London. Notably, these areas have all been subject to sustained disinvestment, territorial stigmatisation and ill-informed ideological attacks on social housing as an incubator of social problems.

The TCG programme is seen by GCC as a significant opportunity “to transform areas of predominantly social rented stock into new, mixed tenure”, making explicit a typical but unwritten policy assumption that mixed tenure policy should target predominantly social housing areas. In practice, as many critics have shown, the language of ‘mixed communities’ and ‘mixed tenure’ has been at the forefront of ‘gentrification by stealth’, since any ‘mixing’ typically always involves more private and less social housing, and is generally targeted at predominantly social rented neighbourhoods.

The projected shift in the programme from social to private tenure is profound. The figures have been subject to frequent revision, but initial plans envisaged that 11,000 GHA social rented properties would be demolished and replaced by 6,500 homes for private sale and mid-market rent and just 600 new social rented homes. This would represent a staggering overall reduction of 10,400 social rented homes in Glasgow in just one city-wide ‘regeneration’ programme. Around a third of the way through the programme in terms of housing constructed, the current target for new homes has been downgraded to around 5,000 ‘mixed tenure’ new homes, while figures for social rent remain at around 600.

This brutal erasure of social housing by mass demolition has been sanctioned by GHA, GCC and the Scottish Government. ‘Scottish exceptionalism’, with regard to housing policy and practice, does not seem to be so exceptional after all–unless we mean in a negative sense. In such a context, it is clear that a strong independent tenants’ movement in Glasgow is a compelling necessity, but here lies another cost associated with the hegemony of HAs.

HAs have cornered the market in the devil’s lexicon of duplicitous terms such as ‘community ownership’ and ‘tenant participation’. But the narrative of HAs as bold new experiments in local control has always been hyperbolic since ‘community-based housing associations’, as Chik Collins and Peter E. Jones have shown, were already being characterised as ‘the tool of central government’ as early as the 1970s, and a Trojan Horse for the privatisation of public housing. Stock transfer in Glasgow, as elsewhere, was partly sold to tenants on the basis of ‘community ownership’, but the reality for tenants has been more akin to incorporation, regulation, de-politicisation and governmental responsibilisation.

The recuperation of tenants into largely toothless HA tenant committees, legally bound to represent the interests of increasingly corporatised HAs rather than tenants, has drastically undermined independent tenants’ movements across the UK. That HA tenant representation would be ‘primarily symbolic’, and no more than a ‘fig leaf’ covering the real relations of power in HAs, was predicted very early on by Defend Council Housing, and other critical commentators.

In Glasgow, for instance, Gerry Mooney and Lynne Poole have stressed that tenants had no role in the preparation and process of ‘housing stock transfer’ and thus any ‘tenant participation’ post-transfer was clearly circumscribed by pre-transfer decisions over which tenants had no control. Additionally, as Collins and Jones observe, stock transfer was never requested by tenants but rather was always a top-down bureaucratic creature of state policy.

It is possible to draw a parallel here with a radical, rather than liberal, critique of ‘trickle down’ economics: the radical critique is not merely founded on questions of redistribution, or the lack of it, but on the actual control and ownership of economic production and wealth. Likewise, the limits of ‘community ownership’ are not only that tenants have been denied meaningful ‘participation’ in GHA decisions, but that tenants have no real ‘community ownership’, either in a de jure or de facto sense.

It is vital to stress that the mainstream Left has been complicit in housing privatisation in Glasgow. As Collins and Jones have shown, the Labour Party in Glasgow were busy trying to (mis)sell the notion of ‘community ownership’ as an expression of the co-operative tradition to the local labour and trade union movement as early as 1984, through the circulation, dissemination and justification of a briefing paper, entitled ‘The socialist case for community ownership’.

As the authors contend, this proposal directly contradicted what the independent ‘community action’ movement in the city at that point had been agitating for since the 1960s: more power in the hands of local communities, but certainly not the dismantling of collective public provision. Indeed, the community action movement viewed the move as a ‘reactionary’ top-down proposal rather than a bottom-up community approach, thus opposing ‘The socialist case for community ownership’ on actual socialist grounds. At the same time, many in the labour and trade union movement thought it risked ‘complicity with the aims of Thatcher’s government’.

Regardless, the Glasgow District Labour Party proposed the ‘community ownership’ model to central government after the relevant unions dropped their opposition to the plan. Approving the principle of ‘community ownership’, but rejecting the formation of independent co-operatives, central government instead suggested the model of ‘voluntary’ housing associations under the government agency, the Housing Corporation in Scotland (HCiS). In Glasgow, these were characterised as ‘Community-Based Housing Associations’ but they were in fact a ‘tool of central government’ accountable to central government itself.

This model could hardly be justified in terms of socialist co-operation, yet proposals disingenuously proceeded under a bogus discourse of grass-roots experimentation and challenges to housing management paternalism and bureaucratic monolithic landlordism. As such, they represented a precedent for transfer to HAs and it was not long before 25%, 50% and finally, in 1999, 100% housing stock transfer was being proposed. The detrimental results of this transfer, which eventually took place on 2003, I have made all too clear.

Conclusion: Building an Independent Tenants’ Movement

The reality of Scotland’s meagre social housing tenure output, and the erasure of its social housing sector in the long run, gives credence to David J. Madden and Peter Marcuse’s observation in In Defense of Housing that the term ‘affordable’ housing, a favoured term in the HA lexicon, is an ideological tool to legitimize private development: ‘a strategy of the real estate machine rather than a relief from it’. Moreover, the idealised notion of HAs as models of ‘community ownership’ in Glasgow, based on their supposed emergence from housing co-operative principles, was always tenuous, as Collins and Jones have convincingly shown.

In the present, such rosy characterisations have been fundamentally undermined by neoliberal policy, funding cuts, corporate management structures, financialisation and increasing commodification. Contemporary Scotland’s fabled progressive ‘exceptionalism’, in relation to Scotland’s housing policy and practice is mythical. This is reflected in a vast housing privatisation process, and in rapidly dwindling social rent tenure figures for anyone who cares to see.

In this context, an independent tenants’ movement is vital. The formation of Living Rent in Scotland in 2014 is thus extremely important. Not least because it addresses the PRS as well as the social housing sector; a crucial move at a time when the tenant demographic has simultaneously seen a significant decline in the social housing sector and a rapid and volatile increase in the PRS.

For all the reasons above, it is encouraging that Living Rent formed a Tenant’s Union in 2016, which, through members’ dues, will provide a source of funding allowing autonomous and independent development and the avoidance of precisely that incorporation into HA tenant management committees which has befallen the older council housing tenants’ movement. The result of that process is manifest in the current housing crisis, the rapid privatisation of HAs, and their obvious inability to provide a solution to the perennial housing question. HAs, are part of the problem and not the solution. An independent tenants’ movement, by contrast, is a necessary precondition for any progressive housing transformation.

*

Neil Gray is the editor of a forthcoming book on historical and contemporary housing movements in Britain and Ireland entitled Rent and its Discontents: A Century of Housing Struggle.

This article is a revised version of a chapter that will appear in a forthcoming book, Whatever Happened to Housing Associations?, a collection of chapters by tenants, trade unionists and academics that will be edited by Glyn Robbins and published by Red Roof Publishing.

Thank you. This is the most coherent and lively left critique I have read on the consequences of marketization of social housing. You have done us all a great service.

Dougie

I wonder about social housing.

In the years after both wars huge numbers of council houses were built. Some were extremely good but the majority were poorly built and designed. They were sited on the outskirts of cities and a cohesive centre of leisure and employment in these “schemes” was not thought of. The inhabitants were abandoned to either live on welfare or attempt to travel long distances to work elsewhere. There are no decent facilities or competitive shops.

The tenants were taught that it was the Council’s responsibility to effect even the most minor of repairs. The councils wasted huge sums creating and running inefficient and ineffective organisations to maintain the houses. The rates went up by more than inflation every year and the housing stock deteriorated. Many of these houses that were no more than 50 or 60 years old have now been demolished or thinned out in an attempt to create something better.

Thatcher’s right to buy was an unmitigated disaster as almost every decent council house in a well designed area was sold leaving the rubbish in the hands of the council. While this was going on we could all see it coming and I thought at the time that the best idea would be to give the hoses to the tenants; make them responsible for their own maintenance and repairs; let them sell if they wanted and find rented accommodation in the private market. As a necessary corollary it would be essential to supervise and manage the private rental market in a way that is not done at the moment.

Housing in the worst areas would cost little to buy and they would attract those willing to make the effort to improve them. The huge cost of constant repair and refurbishment would no longer fall to the council or subsidised housing associations and the general housing stock would be improved.

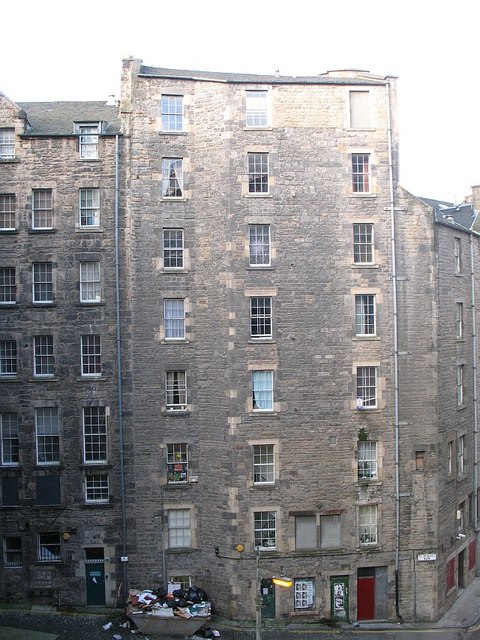

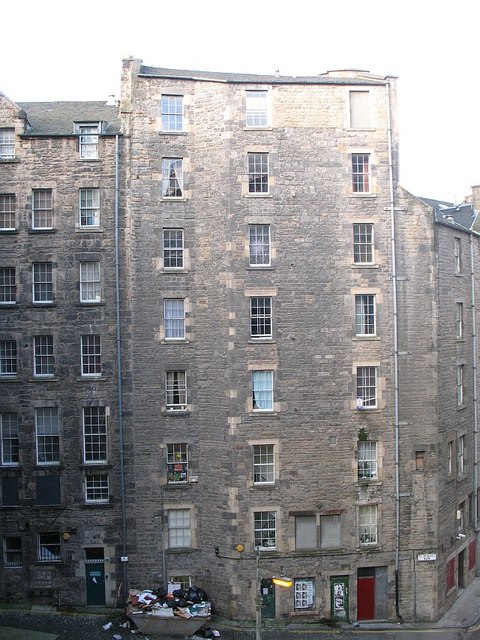

Nice use of an Edinburgh tenement in an article about Glasgow! It’s at the top of Calton Road, near the back of Waverley Station if anyone is wondering. But that shouldn’t detract from a thought-provoking piece. If we really want to change Scotland, we need to start with housing.

While people should have the option of renting you are wrong to suggest that houses in the private sector are too expensive for first time buyers. There are around 40000 each year for sale in all council areas in Scotland with at least two bedrooms for less than £110,000 and most considerably less than that limit. There are up to 100% mortgages available on many of these. The mortgage payments are significantly less than social rents .

Without wishing to get into the specific arithmetic, the median house price in Scotland is I believe around £189,000.

Correspondingly the average wage is around I believe around £26,500.

An average wage earner buying a median house would thus, assuming a 15% deposit of say £25,000, but excluding survey and legal fees, would require a mortgage of something like six times their annual income.

A fairly gargantuan task for a young couple with maybe the mother full time looking after young children.

However not everyone earns the average wage, and many folk are on zero hour contracts and minimum wages. The working poor I think we call them.

What chance of them securing a house, even if that house was available at the aforementioned threshold of £110,000, or lower in council areas across Scotland.

Assuming that you can be fortunate enough to live in a council area with presumably ex council houses for sale, the threshold for securing a mortgage of maybe five times a minimum wage or thereabouts becomes painfully obvious. Factor in a zero hours contract and things become even more grim.

And with many of the ex council houses being bought by speculators to privately rent the background for people on average to minimum wage becomes ever so clear why there is a housing problem.

Housing for living is in a mess. It is a holocaust for those at the bottom end of the income scale and a struggle for many earning more that the average too.

Of course the economics of creating an asset bubble, which asset bubble was founded on credit mortgages that most home buyers require to have, was at the heart of Mrs Thatcher’s economic thinking.

And if you want an example of where this can take a society, consider London where the median value is on a scale where new three bedroom flats cost upwards of a million pounds.

That’s what choking off affordable housing supply does, and you’ll certainly not get a house London for £110,000 or less.

Thankfully the SNP are committing to building more social housing, but there’s a long way to go to assist Thatcher’s disinherited grandchildren.

Yes and the local councils are paying upwards of 450 a month even though these people were already housed in council properties. I honestly think local councils need to look more than just accept the situation , as it is

It’s difficult to know where to start with an article and some comments that are so unhelpful not to mention partial. partial because it misrepresents how we got here and unhelpful because it offers nothing of substance on where we go now.

To begin with how we got here, focusing on, i accept, Glasgow (not my area of strength)…. by the 1960s the City Corporation owned and managed over 160,000 homes and to all intents and purposes housed the whole city and it wasn’t good at it. The community based housing associations that grew up in this period were driven largely either by tenants deeply unhappy with the way the corporation and later the District Council managed their homes and more middle class and often professionally led groups seeking to stop the Councils demolition of traditional tenements. Some of these organisations have grown and spread their operations across other communities but many of them retain much of the focus on community engagement that gave rise to them.

Locally, regionally and nationally a number of specialist associations formed to meet the housing needs of particular groups including those with disabilities, older people and occasionally minority ethnic communities that weren’t well served by Council housing services.

The UK and Scottish Government stock transfer programme of the first ten years after devolution was undoubtedly politically motivated but the deals offered to Glasgow, and Edinburgh for that matter, were genuinely well funded and the investment programmes that came out of them have improved the homes in both cities, the different ballot outcomes notwihtstanding.

The demolition programmes in most of Scotland’s towns and cities that ran from the 1990s through to around 2010, usually badged as “urban regeneration” were largely driven by tenant’s active rejection of many of the homes in those areas. They were “hard to let” because they were “hard to live in” and there are still groups of tenants in central Scotland arguing for the demolition of their homes because they just aren’t good enough.

As to the quality of what is now left, it is very mixed this is true, but the best of it is far from all gone and the worst is a good deal better than it was fifteen years ago. The sector as a whole is more energy efficient than any other, better maintained and fills empty homes as quick as any other.

Our housing system is certainly broken and the right to buy was certainly part of the cause, it should have been abolished in the 2001 housing act, not extended. But it’s gone and the argument is over.

Our 160 or so Housing Associations have far from lost their souls in the way that the sector has in other parts of the UK. The vast majority of the homes they build are for social rent. Just a handful of associations are involved in Mid Market Rent or other “affordable” housing models and fewer still with full private sector operations.

Twenty six of our 32 Councils still have over 310,000 homes between them and most are investing in new homes and growing their stock for the first time in 30 years.

What we have is hardly the basket case described in this article. And without properly understanding what we have and how we got it we can hardly expect to be able to think clearly about where we go.

We have problems in the social sector and in housing policy it’s true. Grant rates for new homes put most of the cost burden on existing and future tenants through their rents (the management of all social housing including debt repayment is entirely funded through rents, services to existing tenants are unsubsidised). Partly as a result of this and the cost of improvement programmes including a substantial and long term energy efficiency programme across the sector, rents have been rising faster than inflation for the last ten years (and the 20 before that for other reasons). As at 2016 32% of tenants in social housing were spending more than 30% of their net income on rents. The sectors claim to be affordable is under threat.

On top of that the community based housing association movement is facing real challenges with governance with around 1 in 8 subject to some intervention because of failing oversight.

And whilst it’s true that we still have 23% of all homes in social renting this is very unevenly spread with 36% or more in West Dunbartonshire and inverclyde and 12% or so in East Renfrewshire and East Dunbartonshire. In many rural communities and some urban areas social housing has all but disappeared, in some newer communities it never existed.

One of the results of the history of urban regeneration and the growth of community based housing associations is the fact that most of the investment in new social housing is in those areas that still have the most and goes to housing associations. Glasgow and four other authorities in the West receive 48% of the investment. The City of Glasgow gets twice that of Edinburgh, our most pressured market with just 19% of the stock in social housing.

Councils have only been eligible for any grant to build new homes since 2010 and at a lower rate than Housing Associations. Councils, who built no homes at all in 2006 now build over 1,200 each year. That should grow to over 2,000 homes by 2021.

I don’t think that the current situation is a crisis but I do think the Edinburgh housing market is on the brink of becoming as dysfunctional as London and as damaging to its hinterland.

And for all the investment the supply of available social housing is falling, in 2016 53,000 or so properties were let, down 8% in as many years, that’s just about the same number as approached their council’s homelessness or housing options service that year. And there are 160,000 folk on council waiting lists. We have perhaps 10,000 people with disabilities in Scotland in homes that don’t meet their needs many of them older owners who can no longer use their whole home. And homelessness is far from fixed, both councils and associations need to do more in that respect.

The list of failings in the system is pretty long, but on balance the social sector is a strength. Yes, it would be better if it had a vibrant and genuinely independent tenants movement. It’s true that much tenant activism has been co-opted into legally defined and officially sanctioned structures but that has not been without its impact. Landlords are better at listening to tenants than they were though they have much to improve on, tenants views do influence rent setting decisions in many instances and local groups are still raising local issues about dampness, repairs quality and dog fouling.

The tenant population is changing, unlike the rest of the population its getting younger, social housing is fast becoming a tenure of working age households and younger people. That’s a challenge both for landlords in modernising services and to the tenants movement to renew itself.

The question is, how do we build on that strength, more specifically, what role should social housing play? what’s the right balance of rent and grant to support new house building? who should live in social housing? how many is too many or too few in any particular community? and how do we increase the % in those areas where it’s too few?

How do communities in decline control the investment in housing in their area to reverse that decline, or to grow?

The list goes on, I just don’t see how this article will help us to find the answers.

An interesting fact based comment that casts more light on the situation.

There are still many areas where social housing streets are the places where the disadvantaged or problem people go to be forgotten and to be out of sight.

I live in Helensburgh, a douce town in many respects but there are several streets that are avoided by the majority of the population. For my sins I have knocked on most of these doors. As everywhere else there is a mix of people. Some have bought their houses and do the best they can, some live in squalor and the houses reflect their lack of care and some are occupied by the dregs of society. A significant number of doors show signs of forced entry for whatever reason.

These areas are where the real challenges are to be found. We do not want any more experiments luke Ferguslie Park where the troubled were sent and the area became notorious. In the end we will continue to muddle along much as we are.

As I said earlier I believe we need to engage more with the inhabitants of problem areas, perhaps with wardens or inspectors, but we need to ensure that socially provided housing is respected and more effort is made by some tenants to maintain the area they live in.

Doghouse Reilly,

Thank you for this nuanced piece in reply to the author of the main article, which I found interesting and insightful in many ways. However, on reading the main piece, I had a visceral feeling that I was reading a piece which was intended as propaganda on behalf of a group which is claiming to have ‘the solution’. I remember similar groups from my days in trade unions.

Many, indeed, most, in those groups were sincere and well-motivated in their intentions, but, often, they had a particular perspective and had a tendency to drift into authoritarianism.

Housing is a very complex area and it often suffers from unintended consequences as well as the really intended consequences of ‘Right to Buy’. In my experience, it is those who live in the various types of housing who actually have the best understanding of their specific circumstances. They need rights and empowerment, but there also have to be some checks to ensure that the ‘common good’ is continually considered.

I was born and brought up in private rented accommodation in a slum area of Glasgow and, remembering, my mother’s continual worries about finding the rent money and the often fruitless attempts at getting the most basic repairs done. We were not eligible for council housing because under the equitably intended ‘points system’ we were relatively low on the ‘waiting list’. I recognise that poor though our circumstance were, there were others in even poorer conditions. I had a few years in other private rented accommodation as a student and as a first-time, full-time worker. I was young, reasonably resilient and optimistic and the flats were essentially a roof-over-my head, while friends and I went out socialising.

Our first year of marriage was spent in private rented accommodation, and then we bought our home, where we have lived for the subsequent 44 years. We did not ‘get on the housing ladder’ – we bought a place to live. We were not making an ‘investment’. This ‘asset’ which we bought has increased in value fifty-fold – aye! right! It is an illusion.

My experience of housing is greatly different from many other people who have had to live in private rented accommodation and so, I do not have the nuanced day-to-day experiences, to form a rigorous view. So, I welcome the main article, the comment by Doghouse Reilly and by several of the other posters.

Alistair Macdonald

With regard to the points based allocation of housing, it used to be said that in Glasgow,that the best way to ensure you were remembered after you died was to put your name on the Corporation Housing List.

More seriously, the family of my best friend at school got a – much envied – transfer from a council tenement to a house with a back and front door. He told me that his father had paid a council official a hundred pound bribe; a lot of money in the 1960s. I am still not sure if this was the truth.

There was lots of “who you know” or backhanders.

In the 1950s we lived in a tumbledown tenement with a toilet down the stair on the landing that was close to John Brown’s shipyard where 24 hour hammering and banging could be heard. My father was friendly with an old woman through work and her son was a leading councillor who later became Clydebank Provost. The mother asked the son to “do something” and it happened almost immediately. We moved to a marvellous wee solid built prefab with a couple of bedrooms, bathroom, kitchen and a garden.

Most interesting comments Dog House Riley.

Social housing as you clearly identify had its problems as was more than exemplified by the old Glasgow Corporation.

Why did Glasgow back in the 60s have the worst housing stock of a major city and in Europe.

Well that’s easy, ageing tenements, failure to maintain, private landlords.

The action areas of the 70s and later were governmental attempts to redress that.

But all that is social is not good and the councils most certainly built a lot that was not good.

To a large extent, and through deliberate policy we have stigmatised social housing. But it doesn’t need to be like that, and there are other options to.

What gives society the best housing for the buck is the big question.

Take two schemes as one might somewhat pejorative describe them.

One is Knightswood in Glasgow built in the in the 1920s whilst the other scheme is Drumchapel also in Glasgow and built in the 1960s.

With both being built to assist eradicate slums, it is not difficult to say which area most folk would describe as being a success and which one not.

So why the difference, both were Corporation housing estates. And why can this not be done again.

What do we need to learn this.

And in the alternative, if we consider politically that it is also good for people to own their homes, what do we need to do to achieve that too.

Increase land available, provide real grants to purchasers and not backhanded payments to developers.

Yes DHR your comments were thought provoking. Something needs to be done about not just housing, but the environment in which we want our society to grow up and develop in.

We don’t have all the answers but by goodness we could with our experiences do do much better.

Dort housing and you sort a lot. Sink schemes, sink people, sink society.

Willie

You point out the difference between the good housing built in Knightswood and the poor housing in nearby Drumchapel.

There is a bit more to the Corporation’s failure. When Knightswood was built in the late 20s, other good quality schemes such as Riddrie were being built. In the late 30s, the Corporation built smaller, poorer quality houses in schemes like Blackhill, Moorpark and Barrowfield. All have been demolished. Post 1945, they built the peripheral housing schemes like Drumchapel. (Even as it was being built, Clydebank Council was building far better houses in Linnvale and Drumry five hundred yards away.) Next came the unwanted high rise flats of the 60s.

Put simply, a successful policy followed by three failed ones.

There were financial constraints on the Corporation but its own failures were immense. It was determined to keep as many people in Glasgow as it could. It ignored the fact that most people did not want to live in tenements or high rise buildings. It made it impossible to build private housing in Glasgow for decades. Its

neglect of property repairs was a long running scandal, again lasting decades.

As to your question, ‘why can this (building good council/social houses) not be done again’, the answer is because hardly anybody trusts the Corporation/Council. East Renfrew and East Dumbarton have prospered by being – in housing terms and, later, in terms of schooling – the opposite of Glasgow. The city is still dealing with the damage the Corporation’s housing failures inflicted over a period of nearly fifty years.

Willie,

Thanks for that.

As you (and Florian Albert) have indicated the former Glasgow Corporation built some very good housing schemes which are still in existence today and are desirable places to live. I think there was also a degree of selection of tenants deemed suitable to live in areas like Knightswood or Riddrie, to take the two examples mentioned. What was known locally as ‘Number 1 Scheme’ in Drumchapel, was also a fairly successful area.

However, with later developments in Drumchapel, there were issues about the quality of some of the housing and its maintenance and there were also issues of social segregation, due to a policy of housing ‘anti-social’ tenants in significant numbers in particular areas. This caused substantial problems for the majority of the neighbours who were good citizens, who then sought rehousing in areas like Knightswood and this led to a downward spiral of social problems in the ‘ghettoised’ areas, and the destruction of the properties and eventual demolition. There was also the issue of amenities.

The ‘right to buy’ took areas like Knightswood and Riddrie out of the public housing stock and the refusal to grant Councils consent to use the revenues to invest in new social housing, meant that the remaining stock got worse, that there was an created shortage in supply of housing, which increased demand and forced up prices, leading to the lunacy of the property speculation which has come close to destroying the economy of the UK.

In Glasgow, there is a large amount of cleared sites and gap sites, which have been empty for decades. They are wilfully being kept undeveloped by property speculators to maintain the shortage of housing and to continue the bloated property bubble. The owners pay no taxes on this land. Such land should be subject to a land tax which increases in proportion to the length of time it lies undeveloped. This will bring such land back into use and should reduce the iniquitous price of land, which is a disproportionately large fraction of the overall cost of housebuilding. With there being more available land, there will be a greater supply of houses, which should reduce demand and begin to bring a bit of sanity back to the property market. With land costs being less, people can invest more in the bricks and mortar and build better quality eco and energy friendly housing.

As a homeowner, who has seen our property rise in value ‘fifty fold’ I have no concerns about the ‘value’ of this ‘asset’ decreasing. It is a place which we bought to live in and, if we sold, we would have to buy or rent at equally inflated prices.

Bring on land reform!

PS To Florian Albert – very many people enjoy living in tenements – Hyndland and Shawlands, for example, have street-upon-street of elegant, spacious, stately desirable flats.

Alistair Macdonald

I would take issue with your chronology vis a vis the decline of Drumchapel. Within a few years of the scheme being built, and before the problem of anti-social tenants arose, there was a clear desire from many tenants to get out. The Corporation dealt with this desire by stopping lateral transfers; i e you could not move from a four apartment in Drumchapel to a four apartment in Knightswood. Predictably, this increased the contempt with which people viewed the Corporation.

The problem of anti-social tenants arose next. Since the decline in Drumchapel was mirrored in almost every other post-war scheme, you have to ask questions about these anti-social tenants.

Where did they all come from ? I suspect that there were few of them to begin with; far fewer than might be assumed. The real problem was that their unacceptable behaviour was ignored and more and more people took advantage of this laxity. A similar story unfolded in Glasgow’s schools; disruptive behaviour was tolerated and became endemic.

Selling off council housing did not start till the early 80s. By then much of Drumchapel was past the point of no return.

You are correct about there being fine tenements in places like Hyndland. However, the people there have chosen to live in them. In Drumchapel, houses were allocated by the Corporation to people whose only alternative was the slums or near slums they wanted out of. Also, people in Hyndland would not be bullied into accepting anti-social neighbours.

Private builders, like Wimpey and John Lawrence, responded to Drumchapel, not by building tenements but by building thousands of semi-detached houses. Some of these were, and are, situated within a couple of hundred yards of Drumchapel itself.

I worked in Drumchapel for a period of five years in the first half of the 1970s. I also had a number of friends from primary school in the 1950s who were amongst the first families to move into Drumchapel and most were bussed daily from and to Drumchapel to continue at the same primary school.

Many of them lived in Number 1 scheme and, despite what you say, it continued to be a fairly successful area. In the 1960s and early 1970s the three secondary schools were producing some very successful students, but this tailed off very sharply by the mid 1970s. By the 1970s, when I worked there, some parts of Drumchapel were really very difficult and many of the ‘aspirational families’ – with fathers who worked in John Brown’s, Goodyear, etc – were moving back into nearer the city centre and Knightswood was a popular choice, but others moved into places like Hardgate and Westerton. So, I agree that by the sell off of council housing substantial parts of Drumchapel were in severe decline.

I think the posters to this article have covered in a fair amount of detail, the many problems which contributed to the decline and failure of a number of ‘schemes’ in Glasgow.

In many areas Stock Transfer meant taking down the sign that said “Housing Department” and replacing it with a sign that said “Housing Association”. Stock, tenants, management and attitudes were not changed. Managerial attitudes are often reminiscent of those days when the motto was “Dae hwit yir telt.” There are exceptions and I like to think I am the tenant of one of the Associations that is different. I have come to site on the management committee and struggle against the perceptions of the past about “Cooncil hooses”

Whilst an interesting read it is clearly not very objective. I work for a HA and maybe my opinion won’t be viewed as being objective either but I think some points have not been considered. Quality of housing is very important, the standards that need to be met are increasing all the time. The SHQS standard has resulted in the rented housing available through RSL’s has had to comply with the criteria set out. This has been tough for a lot of Associations and Local Authorities, generally HA’s have higher compliance rates for SHQS than Local Authorities, this would suggest better quality housing. Now the EESSH standard is being looked at and again it looks like HA’s and their stock are going to have higher compliance for this standard than Local Authorities. In addition to this, significant numbers of new housing is being constructed by HA’s, additional HAG funding is key to this but so is the ability of those bodies commissioning the new builds to borrow money for this. It should be noted Local Authorities etc all have to borrow as well. Borrowing, managing expenditure and increasing stock numbers along with all the other requirements needs sage business management abilities. HA’s generally don’t build massive schemes but through section 75 it is integrated within newbuild private developments. From personal experience buildings that have been empty for many years have also been remodeled and turned into quality housing. Different tenures are dictated by what tenants and customers want rather than being driven by HA’s, mid market rent is aimed at those who earn more while social rent is aimed at those earning less, this seems logical to me. Affordable ownership is sometimes required to make new build schemes viable but most HA’s will use this to supplement new build rented stock It should be remembered that as charities HA’s can only earn a small profit however as not for profit bodies most profit is reinvested in either improving stock or increasing numbers of units. Well managed HA’s have strong boards with good tenant representation on them. They do however require people with a good understanding of business as well. Some small locally based HA’s have struggled to cope with the requirements of the Housing Regulator and have experienced governance problems which mean they have ceased to be, mergerd or become part of a group. These actions have generally been taken to ensure that tenants recieve the best service and housing possible. Tenants do know what they want but there is a need to think bigger, to think about what’s best for all not for the few. I agree things could be better but things are improving.

I live in central london but the capitulation of HA’s to the affordable rent myth rings true.Unfortunately they have become the new frontier on covert privatisation.Brilliant article and thoughtful replies

By the 1980s, Glasgow city council was Europe`s biggest landlords with about 160,000 houses – and facing insurmountable problems. 1) There was political gerrymandering through trading cheap rents for votes. The housing convener took great delight in decrying the idea that tenants should pay realistic rents. 2)There was bad management though insufficient income to pay for routine maintenance and repairs. So more areas became sink schemes. 3)There was a political failure to act against bad tenants. Moonlighters popped up, quietly rehoused in another area…at least one case where a husband and wife rented two council houses in the same block (one was rented out!)…after complaints from neighbours two “business girls” were “transferred” from Drumchapel and opened up business from another council house in Knightswood. The government eventually wiped out the huge housing account debt by “hiving it off” into a housing association. Some 30 years later, Labour finally lost control of George Squre.

Many thanks to the author for a very interesting read, I would like to make a few small additional points.

The possibilities for tenant groups to be ineffective in involvements with HA’s were very clearly demonstrated by the events at the Wellhouse HA in recent years. http://www.eveningtimes.co.uk/news/15366536._Deeply_disturbing__failings_leave_Glasgow_housing_association_tenants_at_risk_while_bosses_buy_cars_worth___50K/

However HA tenants can note with interest the rent challenge made in Partick by tenants

https://www.livingrent.org/glasgow_members_win_massive_rent_reduction

and take heart from the news that HA’s are now covered by FOI legislation, which may well prove to be a very useful weapon for those seeking information. https://www.holyrood.com/articles/news/housing-associations-come-under-foi-laws-minister-confirms?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Holyrood%20Morning%20Roundup%20template%200712&utm_content=Holyrood%20Morning%20Roundup%20template%200712%20CID_bd3a7a0472abd1edf6413c8b2523fd54&utm_source=Email%20newsletters&utm_term=Housing%20associations%20to%20come%20under%20FOI%20laws%20minister%20confirms

Interesting arguments made by Neil Gray in his article.

Mainly refuted by Doghouse Reilly in his nuanced reply.

In addition others have commented, particularly in relation to Glasgow, on the dire state of the Corporation/Council stock held up until transfer to Glasgow Housing Association. Let us not forget that, at the time of transfer to GHA, the Councils’ Housing Department was all but bankrupt AND dragging the City down with it.

However, as I have always understood it, GHA was only ever intended to be a transition body prior to the ex-Council stock being transferred to local community control. Two things mitigated against this.

1) The desire within an organisation mainly staffed at the time with ex-Council staff to become City Housing MII; and,

2) The barriers erected to further transferring stock to local control.

In the event it took considerably longer than envisaged for ‘second-stage’ transfer to come about.

On the separate matter of community controlled housing associations not beeing controlled by members of the community they serve this is simply not true.

The vast majority of Scottish HAs are controlled by local committees comprised of tenants and residents: in many cases the tenants having a majority on the committees on which they sit. It is disingenuous to infer or suggest otherwise.

One area I will agree with Neil Gray is that, unfortunately, there are a few organisations who are building houses for ‘mid-market’ rent as opposed to social housing. However I do not necessarily see this as detrimental to urban renewal nor to the areas in which it is happening.

In short, using the example of English HAs in comparison, what would you rather have? A Scottish HA controlled by a committee of local residents, be they tenants or factored owners, or an English HA controlled by business people with no ties to the locality, no tenants/residents on their boards and run effectively for profit?

A quote from a submission made by Glasgow and West of Scotland Forum of Housing Associations to The Infrastructure & Capital Investment Committee at The Scottish Parliament in 2010:

“the decision to create The Wheatley Group and for Glasgow Housing

Association to become a subsidiary of Wheatley was made by GHA’s

board (under GHA’s constitution, its board are the only shareholding

members). More than 40,000 GHA tenants had no say in the

decision, nor will Wheatley’s Board be directly accountable to GHA

tenants for its current plans to expand the Group’s activities, even

though the Group’s main assets are tenants’ homes.”