From Paris to Nantes, State Violence 1968-2018

When a journalist called out French President Emmanuel Macron in a televised interview last month for misnaming his centrist party En Marche [Onwards] rather than En Force [In Force], he was accused of a brash interview style.

But among many French voters, his comment resonated strongly.

Since the day of his election nearly a year ago, Macron’s spectacle appearances on the world stage have seen France’s youngest President since Napoléon win over the global liberal elite.

The moment he walked through the courtyard of the Louvre Palace in Paris – alone and solemn – in a long black coat to the tune of the European anthem Ode to Joy will remain a defining moment of his Republican rule.

Sharp, eloquent and self-assured, 12 months after taking office, Macron ploughs ahead with his ideas and vision.

A former philosophy student and avid reader, Macron is no doubt familiar with Machiavelli’s reflections on how to be ruler and “whether it be better to be loved than feared or feared than loved?”.

Machiavelli’s concludes “it is much safer to be feared than loved” and Macron seems to have taken on the advice.

With less than a quarter of the votes in the first round of last year’s election, Macron yet used ordinances to speed up the legislative process to reform and “modernised” the country’s Labour laws – a long-standing contentious issue.

In Macron’s Republic there is so far little space for dialogue.

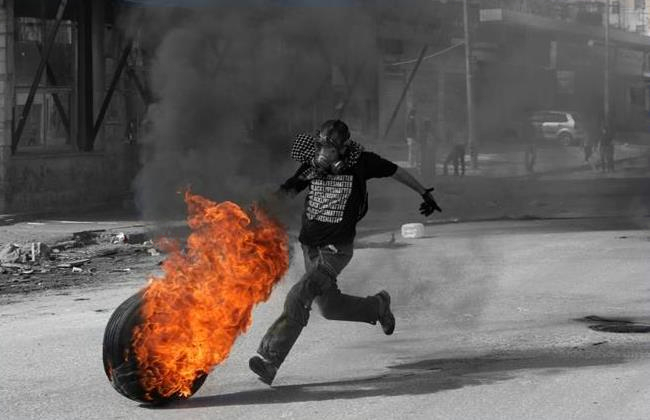

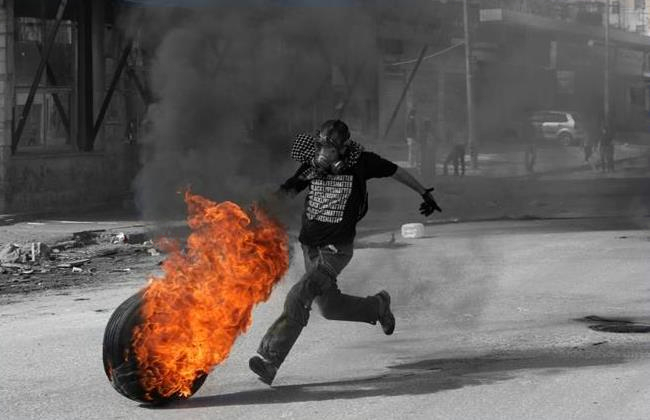

But the most poignant example of Macron’s forceful presidential style are the images of violent clashes between riot police and anti-capitalist and eco-warriors protesters at the illegally occupied site of Notre-Dame-des Landes, in western France, also known as a Zone to Defend (ZAD).

In 2008, environmental activists joined a few farmers on the site and set up a protest camp against plans to build a new airport.

In January, following a decade of opposition, the government abandoned plans for the airport and gave an ultimatum to the two to three hundred zadists (ZAD residents) on the site to regularise their status by registering for individual farming projects or face eviction.

For the state, the zadists are illegally occupying land to which they have no rights. For its eclectic group of residents, the ZAD is more than a contested piece of land but a home in an organised community living on the margin of society and which advocates an alternative way of life, away from the mass consumerism destroying the planet and worsening inequality.

The zadists built homes in bricks and wood and over the years a bakery, a brewery, a radio station, an online newspaper and a weekly vegetable market were also created.

This was a social experiment. Some may say it was a success. Others will point out to a divided movement of people opposing state authority.

The ZAD was a thriving parallel world to Macron’s own reality as a former Rothschild banker. But under French law this utopian project remains illegal and despite the government’s ultimatum, many zadists refused to leave.

Early April, the government sent 2,500 police officers to evict the zadists. The operation turned violent and soon images of police throwing tear gas to protesters in wellies went viral on social media.

But the violence came from both sides. Footage also showed young people in balaclava throwing what is believed to have been petrol bombs to the police, which accused radical left groups to have used the movement to spread disorder.

The images were shocking. It looked just like civil war. The zadists have estimated up to 300 people have been injured, some seriously. Among the police, dozens of officers are reportedly injured.

A group of zadists is now preparing to take a case to the Défenseur des Droits, an independent rights mediator which is responsible to investigate reported claims of police misconduct.

Luce Fournier, a spokesperson for the group VigiZAD, told independent French media Mediapart the complaint included allegations the police used offensive GLIF 4 grenades which contains TNT explosives on protesters.

Fournier added the group was considering further court action against the French state over its abuse of force and violence.

“This is a first step and it will help us gain support for future court actions,” she told Mediapart. “Given the level of violence which took place, we must respond with all available options and we do not exclude any legal challenges,” she added.

The operation to evict the ZAD is reported to have cost €300,000 a day of taxpayers’ money – reaching an estimated total of €3m.

Authorities say 29 of the 97 structures on the site have been destroyed and according to French newspaper Liberation, a delegation of zadists have since registered 40 “mutually dependent and collective” projects with the authorities.

This was not the first time French authorities attempted to take back control of the ZAD. In 2012, a similar operation failed to clear the site after the government u-turned following public outrage over the violent scenes.

But unlike his predecessor, Macron made the choice of an authoritarian crackdown on the ZAD – choosing to be feared rather than loved.

In an interview with French television channel France 3, Macron said he had kept his promise to restore “the Republican order” on the site, denouncing “those who are there to cause disorder”.

“The people who are protesting are people who are illegally occupying public and private land. But they no longer have a reason for their protest since they will not be an airport. So we are doing what citizens are expecting from the state – we are restoring the Republican order,” he said.

The incident stirred up a bags of mixed emotions among the French population.

Some local residents have long resented the ZAD and its residents for appropriating the land without paying their dues. Others have continued to bring their support towards a community which for a decade has ardently tried to live a much simpler life closer to the earth – sometimes on the edge of outright poverty.

But above all, the force and scale of the police operation on the ZAD has brought back other memories of a different time when groups in society decided to defy the authority of the state.

This was the biggest police operation for a public order matter since the student revolution of May 1968, which 50th anniversary is being commemorated this month.

Back then, public opinion was shocked and divided over the pictures of students firring cobblestones from behind barricades blocking the streets of Paris in response to police tear gas and truncheons. These pictures now form part of a collective memory.

The student movement carried the ideals of a generation rejecting the conservative morality, customs and values of traditional society. May ‘68 was a generalised strike action but it is the students which remain the most symbolic aspect of what commentators at the time called a “revolution”.

Critics saw the student movement as little else than a violent attempt to spread disorder and chaos. In this respect, parallels can be drawn between the way the events of May’ 68 and what happened at the ZAD were perceived by an unsympathetic part of society.

In both instances, the heavy-handed actions of the police to stifle public disobedience has divided opinions.

But in all other ways, there is little to compare between the isolated incident at the ZAD and the movement which swept across the whole of France 50 years ago and which legacy in liberating customs and ideas continues to resonate today.

What was once seen as radical in May’ 68 is now perceived as a keystone moment in the construction of modern France.

The rejection of authority in the name of utopian ideals have played important roles in fostering communities and challenging societies. But what happened at the ZAD was not an all-embracing movement to change the system at its root. In many ways, it was a self-centered initiative of a few carrying out an alternative experiment.

What legacy the ZAD will bring to France’s anti-capitalist movement is yet to be seen.

A year into his presidency, Macron has asserted his strong presidential style, powering through a string of promised reforms – fearless.

His zealous attitude fascinates political experts and commentators who invented a new word to describe Macron’s ruling style: Macronism.

Macromism is not a defined concept but rather a way of continuing to ask the question who is Macron?

A young and ambitious minister in the year ahead of the vote, he suddenly rose through the ranks and unexpectedly announced his candidacy to the presidency. Often compared to Jupiter and Napoleon for his commanding behaviour, he is a staunch European and a great believer of a more integrated EU.

Macron has seduced widely on the world stage – thanks in parts to his knowledge of English – and in line with Machiavelli’s advice that “one should wish to be both” feared and loved.

One person who appears to appreciate him dairly is no other than US President Donald Trump.

The pair’s “bromance” reached a new high during Macron’s visit to Washington – the French President being the first head of state to attend an official state visit to the US.

They were kisses and hand shakes, tree planting and compliments all around. But when it came down to business, Macron delivered nothing less than what the liberal elite expected of him.

Strong words on the importance of the Iranian nuclear deal and the urgency to tackle climate change may have irritated Trump but not enough to break his strongest relationship with any European leader.

Meanwhile, Macron used his special relationship with Trump to act as an indispensable bridge between the US President and the rest of the western world watching.

Even Macron’s critics will have to admit that the French President is a master in diplomatic and foreign relations, which have won him what seems like unconditional support from some parts of the British press.

Macron may be loved abroad but back in France there are fewer distractions from the fact his authoritarian stance at home is inspiring both fear and distrust.

Macron’s two faces – one feared and one loved – may provide some insight into what his macronism ruling style may hold in the future.

While he struts on the world stage, his term in office will ultimately be judged on domestic issues by French voters.

I heard French author Alexis Jenni speak at the Edinburgh Book Festival, who spoke of a French collective trauma over their colonial period, which professional historians avoided, and were not taught in schools. He said it was easy for ordinary citizens like him (a science teacher) to find the facts if they looked, but the providers of French culture did not appear to be looking. He was moved to write a novel about it:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Art_fran%C3%A7ais_de_la_guerre

There arose a French identity debate (he said), and France even had a Ministry of Identity.

Napoleon was an imperialist. What has been Macron’s contribution to this colonial-era retrospective soul-searching?