A New Dawn Fades – Creative Scotland’s Killing of NVA

Neil Cooper argues that Creative Scotland’s debacle must end now: “It may be too late now for or NVA, Fire Exit, Inverleith House and all the others killed by Creative Scotland. If so that’s as heart-breaking for those companies and institutions as it is shameful for those who sanctioned the decisions that directly caused their downfall.”

Neil Cooper argues that Creative Scotland’s debacle must end now: “It may be too late now for or NVA, Fire Exit, Inverleith House and all the others killed by Creative Scotland. If so that’s as heart-breaking for those companies and institutions as it is shameful for those who sanctioned the decisions that directly caused their downfall.”

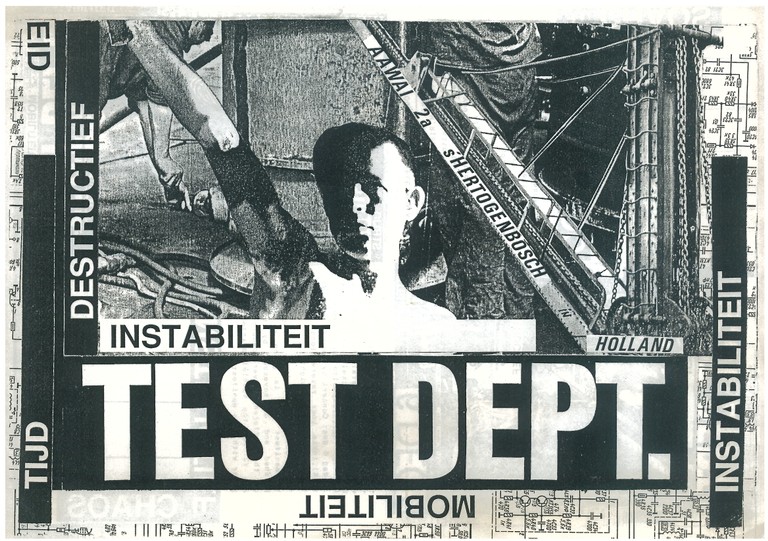

It must have been about sixish on that cool, dewy Mayday morning in 1988 when I was approached by the man I now know as Angus Farquhar atop Calton Hill in Edinburgh. At the time, I only recognised the kilted and bunnetted figure who offered me a bannock and a blessing for luck as a member of Test Dept. The NME-championed industrial agit-prop ‘metal-bashers’ had earlier lined up with massed drums and pipes between the pillars of the Scottish National Monument’s half-built folly in front of several thousand revellers to see in the day as part of a ritual for Beltane.

This reconstituted Celtic ceremony had come at the end of a procession spear-headed by dancers covered in blue or red body-paint, and led by a flailing May Queen. This white-robed powerhouse positioned herself at the centre of the folly flanked by Test Dept’s black-clad quartet pounding their sturm-und-drang way towards dawn. Now here she was standing beside this unerringly polite if possibly pissed member of the group in serene silence as he handed me a bannock before kissing me on the cheek by way of a similarly spirited good luck charm.

I now know that the May Queen was Laban-trained choreographer and dancer Liz Ranken, currently an associate artist and movement director with the Royal Shakespeare Company. I also know that her costume was created by art-school trained Butoh dancer Lindsay John, who was ill and unable to take part alongside the body-painted sprites who leapt about the hill. I now know as well that the late Martyn Bennett played the pipes that night, and I half remember Hamish Henderson singing Freedom Come All Ye, but none of that mattered to me then.

What mattered was that such a spectacle seemed to tap into the spirit of a then unregulated free party scene that would give rise to rave culture, here married to more traditional musical forms in a way that is now commonplace. Even better, it was happening in a public space opposite St Andrew’s House in a still to be devolved Scotland. And that was making a huge political statement, about the right to free assembly, and about self-determination.

What mattered was that such a spectacle seemed to tap into the spirit of a then unregulated free party scene that would give rise to rave culture, here married to more traditional musical forms in a way that is now commonplace. Even better, it was happening in a public space opposite St Andrew’s House in a still to be devolved Scotland. And that was making a huge political statement, about the right to free assembly, and about self-determination.

That first modern revival of Beltane had been initiated by Test Dept, whose revolutionary rhetoric was forged in the rust and real-politick of closed-down factories. Here they transformed the leftover fire and steel into a musical assault on western capitalism with military precision and constructivist artistry. In hindsight, for me, at least, while there would be several other Test Dept spectaculars beyond Beltane, this looked and felt like the spiritual beginning of NVA, the environmental arts pioneers who would move into the great outdoors for a series of great adventures that would span over more than a quarter of a century.

NVA was led by Farquhar, a key member of Test Dept. The organisation’s initials stand for nacionale vita active. NVA said this ‘expresses the Ancient Greek ideal of a lively democracy, where actions and words shared among equals bring new thinking into the world.’ As ambitions for an arts group go, it made quite a statement.

Back in 1988, the factories were pretty much all gone, either flattened, left derelict or else bought up by corporate property developers to be converted and reinvented as edgy apartments for urban living. They’ve no doubt ended up as the sort of bland conurbations without any history to call their own that are currently sucking the life out of every city on the planet. Outdoors, the land still gave the impression, in 1988, at least, of being owned by all and none, and the potential for transforming it into a living spectacle born of the landscape itself was up for grabs. Almost thirty years on, Beltane is still a fixture of Edinburgh’s cultural calendar, while NVA have blazed several trails in an increasingly monumental but totally transitory series of environmental interventions.

NVA’s announcement this week that it will be closing forthwith comes on the back of the company being turned down for regular funding by Creative Scotland. For anyone who has ever been soaked, windswept and exhilarated by being immersed in an NVA creation, this is a tragedy. As is too the organisation’s reluctant withdrawal from reinvigorating St Peter’s Seminary, the Cardross-based modernist architectural wonder which lay empty and unloved for years before Farquhar and co invested a decade attempting to restore it.

While St Peter’s looks set to be put in the care of Historic Environment Scotland, NVA’s departure from the project is a civic and artistic disaster. Beyond both decisions, these two tragedies signal one more nail in the coffin of the beleaguered arts funding body who thought not supporting NVA was a good idea.

While St Peter’s looks set to be put in the care of Historic Environment Scotland, NVA’s departure from the project is a civic and artistic disaster. Beyond both decisions, these two tragedies signal one more nail in the coffin of the beleaguered arts funding body who thought not supporting NVA was a good idea.

NVA’s announcement comes hot on the heels of Creative Scotland’s humiliating reversal of some but by no means all of their regular funding decisions after theatre companies such as the internationally renowned Catherine Wheels were initially cut. As well as NVA, David Leddy’s Fire Exit theatre company was turned down for RFO status, as was Glasgow’s pioneering artist-led gallery, Transmission. While Catherine Wheels, the Dunedin Consort and three other organisations had their funding decisions reversed, the cuts against Fire Exit, NVA, Transmission and others remained.

For long-time Creative Scotland-watchers, leaving some of the most imaginative, outward-looking and risk-taking arts organisations in the country without a secure footing to plan future activity looked very much like lightning striking twice. Back in the last RFO funding round in 2014, when announcements were made to cover 2015-18, those who lost out included Stewart Laing’s acclaimed theatre company, Untitled Projects.

It’s interesting to note that while Creative Scotland failed to recognise the artistic worth of Untitled Projects, Edinburgh International Festival did. This happened first with a 2015 remount of Laing’s brilliant Paul Bright’s Confessions of a Justified Sinner, an event which tapped into Scotland’s underground culture which Farquhar, Test Dept, Beltane and NVA invoked.

This year Untitled are at EIF again with The End of Eddy, an audacious staging of French nouveau enfant terrible Edouard Louis’ wave-making autobiographical novel that looks at class, violence and sexuality in unflinching fashion. This is great news, but imagine what work has undoubtedly been lost because Creative Scotland are unable to recognise the genius they have on their doorstep because it didn’t fit in with some stupid, ill-conceived and ideology-led box-ticking exercise.

Also turned down for regular funding in 2014 for the 2015-18 period was Inverleith House, the former keeper’s residence contained within the grounds of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh which was the original home of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Once SNMG moved on, under the guidance of RBGE’s then director of exhibitions Paul Nesbitt, over the last thirty years Inverleith House became a world-renowned platform for contemporary art.

The outcry the subsequent closure of the programme for Inverleith House in 2016 provoked caused a Scottish Government working group on the future of the space to be set up. This in turn provoked something of a U-turn by RBGE middle managers following an extended closure of Inverleith House’s contemporary art programme. While there are currently no artistic staff in post at RBGE, an advertisement for a Head of Exhibitions has recently appeared. The damage, alas, has been done, and the chances of Inverleith House’s contemporary art programme being restored to its former greatness are slim.

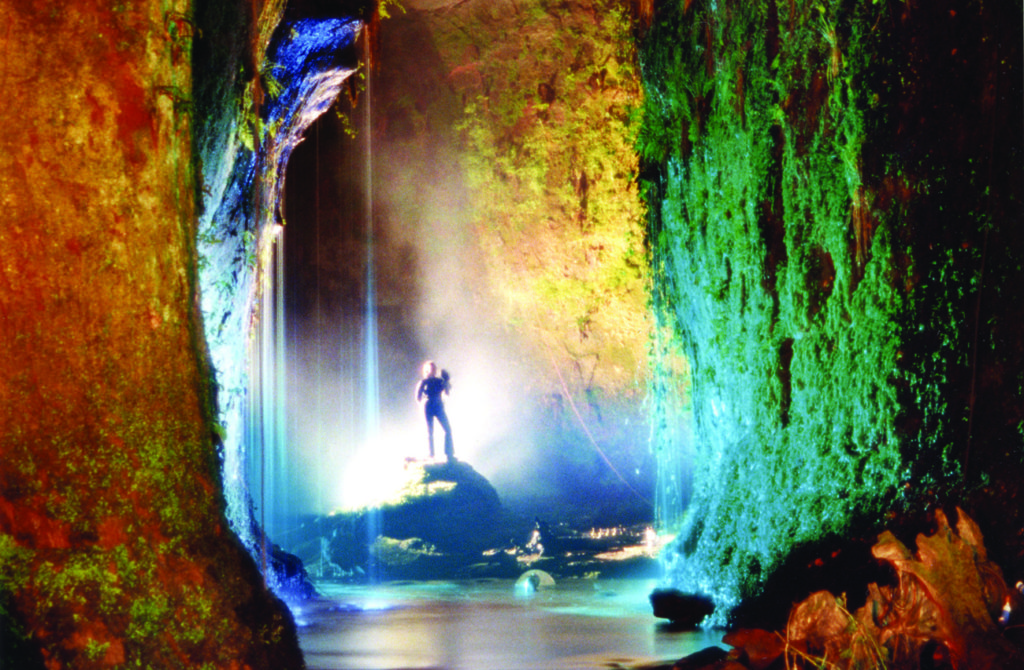

All of this is umbilically connected to the closure of NVA, whose early outdoor work includes The Secret Sign, a ‘walk in the dark’ along the Devil’s Pulpit in Finnich Glen near Loch Lomond in 1998. Two years later, they produced The Path in Glen Lyon, Perthshire. In 2002, Fall from Light was a sound-and-light-based promenade through the South Ayrshire locations for Tam O’Shanter, and formed part of the Burns an’ A ‘That festival. A year later again, NVA created The Hidden Gardens, a permanent transformation of industrial wasteland at the back of Tramway in Glasgow into a living environmental monument to peace.

All of this is umbilically connected to the closure of NVA, whose early outdoor work includes The Secret Sign, a ‘walk in the dark’ along the Devil’s Pulpit in Finnich Glen near Loch Lomond in 1998. Two years later, they produced The Path in Glen Lyon, Perthshire. In 2002, Fall from Light was a sound-and-light-based promenade through the South Ayrshire locations for Tam O’Shanter, and formed part of the Burns an’ A ‘That festival. A year later again, NVA created The Hidden Gardens, a permanent transformation of industrial wasteland at the back of Tramway in Glasgow into a living environmental monument to peace.

In the last decade and a half, NVA collaborated with numerous arts organisations. In 2005, the same year sound and light installation The Storr appeared on the Isle of Skye, the company took part in the Glasgow Festival of Light with Radiance. This featured a visual art programme developed by Katrina Brown, with organisations involved including Transmission.

In 2007, NVA worked with the National Theatre of Scotland and Barry Esson of sonic arts producers Arika Industries on Half Life, which took place in Kilmartin Glen in Argyll. A year later they lit up the glasshouse of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh with Spirit, which formed part of that year’s Chinese Lantern Festival.

As part of the 2010 Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art, NVA presented the 1960s Dutch Provo inspired White Bike Plan. Perhaps most ambitious of all, in 2012, Speed of Light was a fusion of public art, sport and choreography presented on Arthur’s Seat as part of Edinburgh International Festival and the London 2012 Olympic cultural programme. As well as straddling all twelve of Edinburgh’s festivals, Speed of Light went on to Yokohama, Salford and Ruhr.

And then came St Peter’s, the neglected architectural masterpiece championed by Farquhar, NVA and others, but which in the end simply couldn’t be brought back to life without a far greater investment of time, energy and resources which nobody seems to have.

What has been achieved on the St Peter’s site over the last decade, however, has been heroic. Hinterland marked the launch of Scotland’s Festival of Architecture 2016, and opened the doors of the former seminary to a wider public for the first time in thirty years to witness a suitably transcendent spectacle of sound and vision.

“Despite a catalogue of ineptitude, jaw-droppingly bad decision making and an apparent ignorance of the constituency they are supposed to be serving that borders on self-parody, those at the very top of that funding organisation somewhat miraculously still have jobs. Those working for NVA don’t.”

What will now be NVA’s final work, Make Me Up, is scheduled to appear across the UK this coming November. This new film by Rachel Maclean, who represented Scotland in the 2017 Venice Biennale, sees Maclean conjure up a comic-horror dystopian future where a group of women are trapped in a vicious reality TV-style competition. Filmed in St Peter’s, Make Me Up commemorates the 100-year anniversary women in the UK being first given the right to vote.

As this far from definitive list shows, NVA’s work can’t easily be put into a particular box. It is neither theatre or visual art in the Waverleygate sense of those words. Rather, the company has occupied a unique position within Scotland’s artistic landscape both at home and abroad. That position, alas, has just inexplicably been razed away.

NVA were post-industrial mavericks. Led by Farquhar and executive director Ellen Potter, the company drew its artistic ideas from the counter-cultural European avant-garde, Joseph Beuys inspired environmentalism and situationist-styled psycho-geography. Crucially, these ideas were applied in a civic context that saw NVA collaborate with festivals at a local, national and global level. In this way they both infiltrated official culture and laid down the foundations for future cultural explorers to burrow their way through the ruins of town and country and reinvigorate them with fresh artistic life. In Edinburgh, for instance, the Hidden Door festival has been excavating neglected spaces and reimagining them in ways Test Dept / Hidden Door might once have done.

Throughout a series of increasingly ambitious works, NVA avoided being co-opted as a circuses-and-bread style diversion and retained artistic credibility. At its best, NVA’s work, and the constituent parts required to make that work, was a sleight-of-hand on an epic scale that joined dots between artforms and organisations like few others.

With this in mind, there is no little irony in the fact that NVA has just been killed by Creative Scotland. On the one hand, you have an artist-led organisation headed by one of the most visionary auteurs of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, whose drive and zeal was born of punk and an instinctive opposition to 1980s Thatcherism. On the other, you have a government-sanctioned quango founded on a bureaucratic, managerialist New Labour ideology which an SNP government – an SNP government – has quietly acquiesced to.

With this in mind, there is no little irony in the fact that NVA has just been killed by Creative Scotland. On the one hand, you have an artist-led organisation headed by one of the most visionary auteurs of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, whose drive and zeal was born of punk and an instinctive opposition to 1980s Thatcherism. On the other, you have a government-sanctioned quango founded on a bureaucratic, managerialist New Labour ideology which an SNP government – an SNP government – has quietly acquiesced to.

At that funding organisation’s head are a coterie of middle managers, desperately out of their depth after being parachuted in equipped with little save a passed-down hand-book of the sort of loveless jargon that makes leadership training course graduates feel clever. It takes two minutes, however, to realise that those boardroom-friendly phrases are actually meaningless. Despite a catalogue of ineptitude, jaw-droppingly bad decision making and an apparent ignorance of the constituency they are supposed to be serving that borders on self-parody, those at the very top of that funding organisation somewhat miraculously still have jobs. Those working for NVA don’t.

As has been stated here before, the removal of those senior Creative Scotland managers from their posts – and more than one must go – will solve nothing by itself. This was the case too following the necessary removal of their open-shirted predecessor Andrew Dixon. A veteran of exactly the same management training courses as them, his departure left Creative Scotland’s fundamental ideology intact in the way a time-bomb is left, one wrong move making it likely to blow up in everybody’s faces.

“With this in mind, there is no little irony in the fact that NVA has just been killed by Creative Scotland. On the one hand, you have an artist-led organisation headed by one of the most visionary auteurs of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, whose drive and zeal was born of punk and an instinctive opposition to 1980s Thatcherism.”

If the ideological time-bomb that Creative Scotland was founded on is not dismantled from the top down, whether it’s this time next year, in three years, five years or beyond, be sure that it will blow up, and it will keep on blowing up.

In any other country in the world, artistic visionaries such as Angus Farquhar, Stewart Laing David Leddy and Paul Nesbitt would not just be lauded. They would be protected from bureaucratic bungling and given the resources and the security to make something even greater than they already have done. Instead, they’re effectively being told by Creative Scotland that, despite all the evidence to the contrary, their work somehow isn’t up to scratch. Rather than have some kind of sensible artistic continuum, they shouldn’t get too big for their boots, these arty types, and should go back to scratching around for pennies like everybody else.

As long as this utter failure of ambition, vision and will continues to be allowed to effectively control Scotland’s artistic narrative, those like Farquhar who are already in possession of all three will never be able to live up to their full potential. Perhaps they will quite rightly go somewhere they will be given the respect and the resources they deserve.

It may be too late now for or NVA, Fire Exit, Inverleith House and all the others killed by Creative Scotland. If so that’s as heart-breaking for those companies and institutions as it is shameful for those who sanctioned the decisions that directly caused their downfall.

For Farquhar, and for everyone else involved with NVA, just like that dewy Mayday morning back in 1988 on Calton Hill, it’s a brand new dawn. I hope they’re sharing bannocks and kisses to bring good luck raining down on them for whatever happens next. I hope as well that it’s something to do with actions and words being shared among equals to bring new thinking into the world.

As for Creative Scotland, stop me if you’ve heard this one before, but like I say, nothing’s changed. it’s an organisation that’s never been fit for purpose, and has been a dead quango walking for at least half a decade now. Time to put it out of its misery, rip it up and start again.

“In Edinburgh, for instance, the Hidden Door festival has been excavating neglected spaces and reimagining them in ways Test Dept / Hidden Door might once have done.”

Please inform us as to when Test Department undertook a creative ritual to herald the arrival of luxury flats Neil. Or when they ran a private art school charging 5k a pop.

I have heard nothing good of Creative Scotland. Those who have dealt with it have made dire accusations of a circle jerk with funding being channelled to ‘mates’. But the arts community, the gesso mafia also has to be realistic, there is only so much money that can be channelled to arts organisations before it becomes politically damaging.

Being very much on the fringe of the arts world and not knowing the dynamics within Creative Scotland, I’ve been watching this and wondering. Is it that it’s run by “parachuted in” administrators and perhaps disconnected committee members of the world of “loveless jargon”? Or, is it that Westminster’s austerity programme – choosing to make ordinary folks pay for the fecklessness of the rich – has impacted on Holyrood in ways that has cut budgets in real terms, and forced the mentioned managerialism as a coping strategy?

In other words, is it a people issue or a money issue (or both)?

In choosing not to fund the work of figures like Angus F, is the work that is being funded worthwhile? Or is it an effete opiate, serving so as not to disturb the sleepwalking?

I honestly don’t know, thus these are not daft laddie questions. I’d be interested to hear what informed voices say.

My personal bias would be strongly in the spirit of “nacionale vita active”. I would see that as art that lifts the human spirit, treasuring beauty, nodding to the sacred yet not hidebound by religion, raising consciousness and conscience in the manner that Freire called conscientisation, and all of that – to the discomfort of forces that would undermine the vernacular, the poor, and the future of an inclusive, generous Scotland.

I think Creative Scotland got an OK budget settlement, including a top-up to make up for declining Lottery sales. But there is also no shortage of applicants – I don’t envy them their job of sustaining established performers while also finding the resource to bring in new ones.

I was involved with NVA during the Storr Project on the Isle of Skye – It is important to discuss the legacies that such an organisation left after the event. It is perhaps difficult to state, but the legacy NVA left on Skye was a pride and a self belief in community, as well as the memories of the actual event and the art. I often wonder if the funding agencies really comprehend the importance of such legacies. I will toast NVA tonight, the craic was mighty, the professionalism exemplary. The show was audacious yet possible and is now part of Skye folklore. I am proud to say I was involved in my own small way and hope that Angus and the team find a future to continue being creative….

Should we expect government to fund revolutionary artforms?

Yes.

@Jim Bennett, does meeting requirements of government (or corporate) funding rather draw the revolutionary teeth from projects? There are other ways:

“People from over 85 cities from allover Europe registered as performers and volunteers – the whole project was entirely realized though crowdfunding, donations in kind and voluntary commitment.”

http://1000gestalten.de/en/

“I don’t know anything about Scottish culture but I’m keen to learn”.

When will we Scots ever get a grip o oor ain naition! Importing a meritocracy is for colonies.

I enjoy your writing style genuinely enjoying this website .