Feudal Relics and Colonial Conquests

Forty years ago, the first fish farms appeared in Scotland’s west coast sea lochs. No planning consent was required and as they spread, local politicians and campaigners became aware of the unaccountable and remote body that is the Crown Estate Commissioners. Since 1961, they have been responsible for managing Scotland’s Crown Estate and as their tentacles spread, they began demanding rents and levies from harbours and moorings that had previously invested in coastal facilities but not ever imagined they needed to pay rent for the privilege.

For the best part of 40 years, there has been an active campaign to eliminate the malign influence of the Crown Estate Commissioners by, for example, the West Highland Free Press and politicians such as Brian Wilson and Michael Foxley [for more background on the Crown Estate see also here – Ed]

Scotland’s Crown Estate derives from two sources. The first is ancient rights that belong (or were asserted to belong) to the Crown by default – gold and silver, the foreshore, mussels and oysters, salmon and the seabed. The second are conventional and more modern acquisitions of ordinary property – offices, farms and retail premises. Historically this first set of rights had always administered in Scotland until the 1830s when control went south to London the Crown’s rights to ownerless property and treasure trove which to this day are administered by the Crown Office with revenues paid to the Scottish Consolidated Fund.

Crown property, rights and interests in Scotland have, for centuries ,been defined by Scots law and remain so. For most of their history, they have been administered here in Scotland and the revenue has flowed to the Scottish Exchequer with only a short hiatus between 1830 and 2017. They never, for example, formed part of the civil list when England’s crown revenues were surrendered in 1760.

In other words, this is a distinctive, historic set of rights that belong to Scotland.

But in 2014, in the aftermath of the independence referendum, the Smith Commission recommended that management and revenues be devolved and that management would be further devolved to Scotland’s local authorities

Despite UK Government guarantees that Smith would be implemented in full, legislative competence for the revenues of the Crown Estate was never devolved as it should have been. The Scotland Act 2016 stipulated that the revenues should be paid into the Scottish Consolidated Fund but the Scottish Parliament cannot change this. Nevertheless, with management devolved, a key obstacle to more fundamental reform was removed.

The Scottish Crown Estate Bill was introduced to Parliament in January 2018. This week’s debate on Stage One was preceded by a statement from the Justice Secretary, Michael Matheson:

“For the purposes of rule 9.11 of the standing orders, I advise Parliament that Her Majesty, having been informed of the purport of the Scottish Crown Estate Bill, has consented to place her prerogative and interests, in so far as they are affected by the bill, at the disposal of the Parliament for the purposes of the bill.”

That the Scottish Parliament must defer to Her Majesty in order to legislate is a symbol of the arcane nature of our democracy.

As for the Bill, it disappointingly, proceeds on the normative assumption that the Crown Estate is a coherent suite of assets which by law must be maintained as an estate in land on behalf of the Crown. It does this, in part, because the Scotland Act 2016 and the arrangements for the devolution of the management of the Crown Estate seek to restrain and curtail the Scottish Parliament’s freedom of manoeuvre.

I reject this assumption.

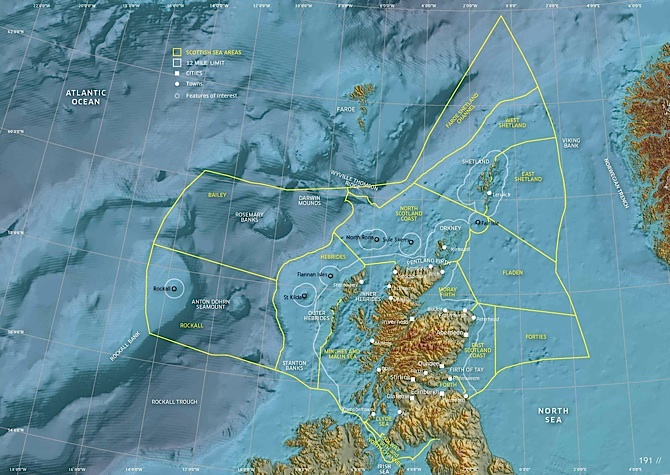

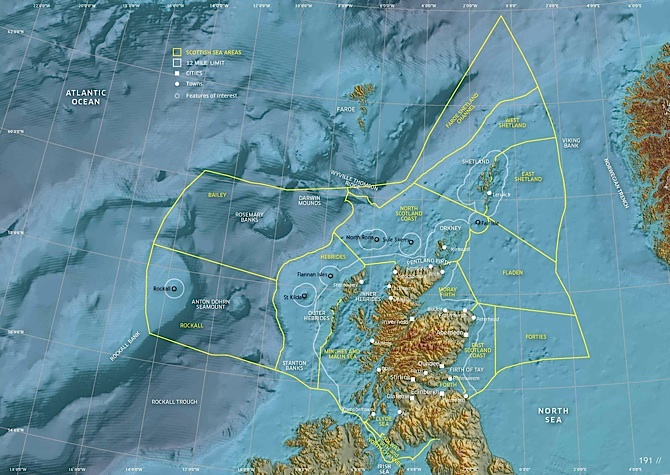

The Crown Estate is both a feudal relic and the last gasp of Empire. It includes gold and silver, rights to which date back to the oldest Scottish Act on the statute book, the Royal Mines Act of 1424. It includes the foreshore and the seabed, rights to both of which have no statutory basis. In relation to the foreshore, the Crown’s rights are said to be patrimonial rights derived from the Crown prerogative but in the words of the Scottish Law Commission, that is merely the “predominant modern theory.” As for Rockall, it was claimed by the Crown in 1955 in Britain’s last formal exercise of colonial power with possession being taken in the name of her majesty by Captain O’Connell of HMS Vidal who was given a royal warrant to seize the rock.

Crucially, Scotland now has the power to sweep away these anachronisms and in so doing free ourselves from the shackles of the 2016 devolution settlement. Put simply, the complex arrangements for managing Scotland’s Crown Estate proposed in the Bill can be dispensed with if we abolish the Crown rights themselves.

For example, despite the transfer of administration in 2014, there is no good reason why the medieval right of the Scottish Crown to naturally-occurring mussels and oysters has any place in a modern statute book. The Bill should abolish this right, confirm the species as ferae naturae – wild animals.

More substantially the Crown rights to the foreshore should be abolished. This Bill provides the opportunity to modernise the legal basis for the ownership of the foreshore and vest title in Scotland’s local authorities directly rather than through a complicated scheme of delegated management. Councils such as Orkney and Shetland have demonstrated over decades that they have the skills and capacity to discharge this responsibility competently and effectively.

In relation to the seabed, where the Crown’s ownership has no statutory basis, the Bill could vest it in the name of Scottish Ministers and create an equivalent to the National Forest Land Scheme to enable transfers of title to Scotland’s 248 local authority harbours and 46 Trust Ports ending decades of legal disputes and conflict between the Crown and many harbour and port authorities.

I will be consulting over summer on detailed proposals to effect the changes described above and will be seeking the support of other political parties to usher in a new era where medieval ideas of property can finally be consigned to the dustbin of history and we can make one small step on the way to becoming a modern, democratic society.

Image credit: Scott Hutchison

An important article which, I think, would benefit from some very careful proof-reading so that its content is not undermined by errors of punctuation, spelling and, I suspect, inadvertent omission.

I should like to echo Michael Stuart Green’s comment. The issue of land and property is a complex one with a fair amount of arcane terminology and concepts with which many of us are unfamiliar. It is essential that the text is proof-read carefully so that there is a text which does not put barriers in the way of comprehension.

When I was studying for a Master’s degree, one of my tutors had a maxim; “Everything is capable of being explained to others at an appropriate level, in a conceptually rigorous way.” It is something which is easier said than done, but, which can be done with a bit of care and practice. If we take, say, some of the concepts of electricity, then we can make these comprehensible, to early primary school age children. This is not claiming that they will know at the level of a post-graduate physics student or an electrical engineer, but that they will have a sound grasp of the rudiments, which by further teaching and learning can be deepened and widened. Misunderstandings which arise early in one’s exposure to a subject, unless quickly corrected, often persist throughout one’s life.

For those of us who are well through our lives and who are encountering this for the first time, such an introductory piece by Mr Wightman is important and, as such should be well produced.

Apologies for the pedantry, but, I think it is worth pointing out. Propagandising can be done very effectively. Propaganda is not just the kind of venal stuff that Josef Goebbels, for example, was propagating, it also includes the kind of morally and socially good information which was delivered when the Welfare State was being established by the post war government.

I think the devolution is generally a good thing, but I’d want the foreshore and seabed to be inalienable, i.e. it can’t be sold off.

In addition to the British Crown Estate’s centuries old exploitation of Scotland’s marine assets, Malcolm Rikfind when UK Transport Secretary sold to the ‘City’ much of Scotland’s major strategic seaports and their foreshore along the Forth, Clyde and Tay thanks to his 1991 Ports Act. Today the ownership of these large and often crumbling port estates and their regulation rests in the hands of offshore equity funds who invariably seek public money in order to revitalise their continued dereliction and obsolescence (e.g. Dundee waterfront). That port sell-off was described by maritime economists around the world as ‘the Anglo Saxon model’ of port and estuary management (i.e. a state giveaway to bankers to make loads of money at our expense). The rest of the world mostly subscribe to the rather more sensible notion that the foreshore including strategic seaport capacity should remain in ‘dominimum populi’, for all to rightfully have access to, and generally owned, administered and regulated by government bodies. The other UK ‘oddity’ known as ‘Trust Ports’ are similarly not public entities and as often as not they tend to work rather more in the interest of (private) trustees than the public. All of these examples of ‘Anglo Saxon’ exploitation (part of the gradually unravelling Union ‘dividend’!) of Scotland’s valuable foreshore should be addressed, as well as the Crown Estate.

Was Canada’s independence botched if 89% remains Crown land?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crown_land#Canada

Or is it a sign that feudalism and empire are still actually with us, albeit kept a bit quiet?

When the first colonists went to the new world they took with them most of the things they thought that they were escaping from. eg. in the book “God’s Frontiersmen” it tells how the established authorities (who had acquired the land for free) were complaining about the new settlers “that they expected to get land for free”.

Feudalism is alive and well, it has simply evolved into many different forms, from leaseholds (in England) private landlords, and Land value tax as in North America, all a means of leaching off the public regardless of the means to pay. You can also include franchises and intellectual property rights. The worst about it all is that the more openings there are for people to exercise such control over others the bigger the drain on the productive sector of the economy. It allows increasing numbers to lie back and skim the cream off of the labour of others, or in some cases simply deprive others of the means to labour

I’d like to defend Trust Ports as I understand them, speaking as a Trustee of Ullapool Harbour. We steward the harbour for the community, ploughing the profits back into the business. None of us are paid except the Chief Executive/Harbourmaster who works his socks off. Under Trust Port legislation we can give away up to 2% of the profit which we do to charitable local causes. All the Trustees I have known take the local interest very seriously and have no way to enrich themselves that I can see.

It would be great to see the back of the Crown Estate who charge rent on the seabed for no discernible public benefit. Just this week we see them selling off their 50% stake in Fort Kinnaird to finance their English estate.

If the only main management cost is the Chief Exec, how come the trusts’ ‘Administrative Expenses’ for 2017 amounted to £2.1m, according to the accounts? The port appears to have one main user and income – Calmac. And the main cost of the upgraded pier and previous upgrades was I understand met by the Scottish Government, yet the trust charges fees to the Scottish Government owned ferry operator for the privilege of using that Scottish Government financed pier? Does that not mean the taxpayer basically gets to pay for the asset twice? What is the real point of a trust with a board of individuals on it, however appointed? With one major port user, whose state owner also finances the port modernisation/upgrade, why not just let state owned agencies/users (Calmac/CMAL) own/run the pier? Other activities such as fishing, leisure etc could be part of Highland Council’s significant port portfolio. What really therefore is the point of the port ‘trust’ and its board, which you seek to defend? Giving 2% of surplus to charity is admirable, even if much if not most of that will be from public sector ferry income, but that is hardly justification for having a trust and board, is it?