The Disposability of the Precarious Worker

‘Our job is to not exist,’ my friend told me in reference to his new minimum wage service job. This accurately poignant observation cleverly summarises the experience of the service industry workers. He didn’t intend for it to, he was only describing the role of a waiter in a high-end eatery. However, it perfectly explains my own experiences in having just been let go from yet another minimum wage job in service because I refused to bend to unreasonable whims.

‘Our job is to not exist,’ my friend told me in reference to his new minimum wage service job. This accurately poignant observation cleverly summarises the experience of the service industry workers. He didn’t intend for it to, he was only describing the role of a waiter in a high-end eatery. However, it perfectly explains my own experiences in having just been let go from yet another minimum wage job in service because I refused to bend to unreasonable whims.

In having read many self-help books in my time, I understand the importance of setting bound- aries, the power of saying no, and the need to own one’s voice. As one of the precariat, I also recognise that the majority of work available to me requires that I cast these rights aside to be ‘adaptable’, ‘flexible’ and ‘cope well under pressure’. These terms are interchangeable with the phrase ‘bowing to oppression.’

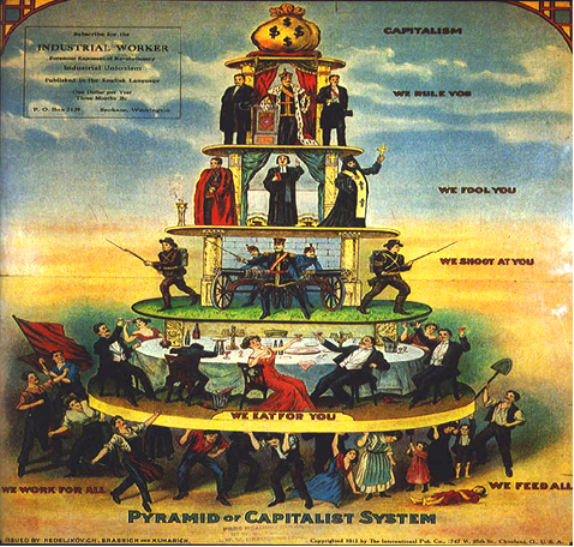

In Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of The Oppressed, his quintessential text on educational reform and revolution, he discusses how educational institutions shape our mindset to fit with the current hi- erarchies. We, the workers, must be dictated to by our masters and accept the demands of our employment even at the expense of our health, families and personal lives. This is all too clearly illustrated by the General Manager of a restaurant who having realised his mistake in scheduling my hours as a cash-in-hand cleaner, without taking into consideration my clearly stated availabili- ty, accused me of becoming ‘confrontational’ and told me ‘it wasn’t going to work out.’

Confrontational? You haven’t seen anything yet, baby.

My friend and I both come from low-income families and to be able to continue our post-graduate studies found it is necessary for us to take on part-time employment to sustain our very existence whilst gaining our degrees. Without financial security to sustain us on our course, we must fit these roles to stay alive. In one world we are taught to be critical and to drive ourselves to explore our environment. In the other, we are told to keep our head down and our mouth shut, the avoid- ance of which is a luxury we cannot afford.

The increasing demands on service workers to work zero-hour contracts, unsociable hours and to accept ill-treatment from employers and customers alike, make for an unhappy work environment. Not only are we expected to put the needs of the business before our own but we must forgo movement up the ladder: our only hope being we may make it to a managerial position where we can then dictate to rather than be dictated to.

When I was sixteen, I worked in a nightclub collecting glasses. On New Years Eve, as I made my way across the dance floor to the bar during the bells, a man in his late fifties grabbed me and forcibly kissed me. The assault was brushed off by the staff: the customers pennies and pounds being of more value than the safety of a young woman in the eyes of the business. It is a brutal thing knowing that the hand which feeds you thinks currency has more worth than you.

This is what happened with this new, upmarket restaurant. For all the investment, all the coin that has been poured into it, they still fail to recognise the value of the humans within their walls. The money from that job was to go towards food in the bellies of my bairns, keeping the electricity on, buying a birthday gift. I have value and my children have value. We deserve to have our needs met more so than the needs of a new fancy restaurant. What they needed was someone who will do as they are told and keep their mouth shut. I, unfortunately, do not have that in me.

The fragile nature of working in the service industry; where you are not only viewed as disposable by the customers but replaceable by the management, is a result of oppressive hierarchy. Service is the key word. We are servants, we are here to serve. Perhaps it is an elaborate ruse to con the middle classes into thinking they have power by providing a platform from which they can play at being master. Being waited on hand and foot, no cleaning, no cooking… all taken care of by the staff. Freire describes this as an attempt to escape oppression: become an oppressor so you are no longer oppressed. But to commit a violent act such as dehumanising a person, even in the mi- croclimate of the restaurant, does not make you free – it makes you a jerk.

My loyalty and submission cannot be bought, we are all collaborators. When I work for someone, I see it as granting them my time and being reimbursed for the inconvenience, not bribed into self-humiliation. How far can we push her? Can we get her to bail on her kids? Deprive her of sleep? No, you can’t – I know my worth.

Checking diseases of affluence on Wikipedia for mental disorders:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diseases_of_affluence

leads to Affluenza:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affluenza

The more affluent you are, perhaps, the more distant from the workings of the world you tend to be, the more ignorant of how your food gets on your plate, and the more likely you are to attribute your good fortune to personal worthiness rather than luck or (precarious) exploitation of others or the enviroment. It may amount to a form of psychosis in some cases.

This tends to be explored to good effect in disaster stories where the social order crumples while the rich are still trying to bribe their way onto the lifeboats.

On reflection, I know someone who wasn’t rich but had impulsive access to easy credit who seemed to love the (forced) displays of respect he got when turning up at restaurants and negotiating two starters for himself. The other notable thing about him was that he was a British Imperialist whose fondest fantasy (as related) was to be some kind of colonial governor in India at the receiving end of processions, presents and pampering. This did not seem healthy.

Excellent. I suspect anyone who has worked almost anywhere in the last 20 years or so will recognise the ideas here. I like the notion of the middle classes having been given an illusion of power in restaurants, hotels etc. You can see the same thing manifest in other areas, the way people drive, treat shop assistants, transport workers, health professionals etc etc etc.

I think it is becoming common among the working classes as well. We’ve been sold the lie that we have power as consumers, we don’t.

Has there ever been a workplace situation in Scotland, wherein solidarity amongst the workers made the exploitation and general abuse of personnel by management impossible? Not in my fifty years of experience there wasn’t. And that included unionised workplaces, where it was often difficult to know exactly who’s side the Union was on.

Post 1979 it became blindingly obvious (to some of us) that employers were out to seize back everything grudgingly conceded in the post-war period. Individuals who chose to resist this managerial reassertion of power were, of course, easily picked-off. I chose to emigrate in my mid-forties, penniless and jobless; a most successful move as it transpired. I write this in the certain knowledge that I’m not a lone-voice regarding the harsh and ofttimes denied realities of Scottish work-culture.

Do you mind if I ask which country you migrated to, Jusef?

Hi Ian, the Republic of Ireland.

Thank you for writing this.

What an excellent article.