The Authentic Andy Murray

In classic Andy Murray fashion, after the downcast press conference, the worldwide tributes and the schmaltzy retirement video by his fellow pros, he gave us all something to cling onto. This week he’s expected to announce if he’ll go ahead with a hip resurfacing operation, which would, if nothing else, improve his quality of life. It’s an operation no singles player has ever come back from, but it might give him a shot at playing again. Keeping us in suspense, one more time.

But if this is to be the end, his career highlights are worth savoring: US Open champion; two-time Wimbledon winner; twice Olympic gold medalist; Davis Cup victor; World Number One. These are remarkable achievements by any measure and for those who have followed his journey there’s an overriding sense of pride and gratitude. Yet there remains a nagging feeling that he could and maybe should have achieved even more. In terms of total match wins, Andy’s in the top ten ever for three out of the four Grand Slams. Between 2008 and 2017, he appeared in 21 Grand Slam semi-finals and 11 finals (the ninth best in the Open era) but won only three.

It’s tempting to indulge in hypotheticals – if he wasn’t playing in the Greatest Ever Era, if he’d been born a few years earlier, or a few years later, he might have double or triple the number of majors. He’d be a multiple Australian Open champion – rather than five-times runner-up. He would have dominated Wimbledon. In a field without the King of Clay, he might even have triumphed on the red dirt of Roland Garros.

But, of course, every player is a product of their own era. Their style of play honed by varying court speeds and innovations in racket technology; their bodies sculpted by the latest fitness regimes and sports science; their boundaries pushed by the success of their peers. Just as Federer, the graceful, all-conquering genius, was forced to add dimensions to his game by an explosive young Mallorcan, all biceps and topsin, so Nadal’s level was pushed to new heights by the ruthless precision of Djokovic, who set new standards for a multi-surface, baseline game. These icons made Andy Murray a better player – as he did them – and when the defining clashes of this golden age are retold, the unprecedented feats eulogised, he’ll be part of the story.

Even against such competition, it sometimes felt like Andy should have more to show for his talent and graft. Few in history have possessed his court-craft or tactical nous, his magnificent backhand or his confounding ability to get another ball back, then another ball back, then another…There’s very little to choose between his game and Novak’s. Sure, the Serb has a more penetrating forehand and a stronger second serve, but arguably the biggest attribute separating the two friends, the main reason one holds three grand slams and the other 14, is not technical or physical, but mental.

Murray is among the fiercest competitors in any sport, one of the hardest workers, an athlete who has used the pain of the most wounding defeats as motivation to claim the most beautiful victories. But he’s generally lacked a kind of emotional equilibrium maintained by his three illustrious rivals. The others have each had their petulant lapses, but their on-court demeanour conveys a steely focus and unwavering self-belief that has at times eluded Murray. In Andy’s moments of greatest adversity, the world could see his demons; his mental torment and physical anguish were rarely hidden from view. The grimaces and muttering, the sarcastic goading of his box, were sometimes difficult to watch, and tended to coincide with an unraveling of his tennis game.

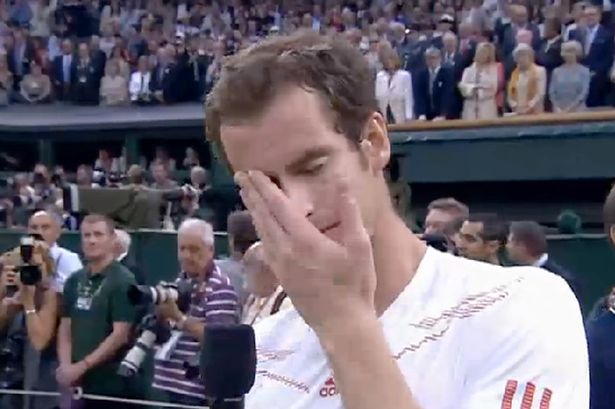

But it’s that same emotional honesty – the wavering voice in on-court interviews, the propensity to let the tears flow, the frankness about his own shortcomings – that makes him more relatable than his consummate, smooth competitors. He’s always provided confirmation that what he’s doing is even harder than it looks. If the Big Three seem to have superpowers, he’s a hero of a different sort – the Everyman, your messy-haired pal going toe-to-toe with sporting immortals. Beyond his titles, it’s this authenticity, and willingness to challenge the status quo with deeds as well as words – most significantly on sexism in tennis – that makes Andy such a role model, personifying a healthy masculinity that is tough yet vulnerable. He might be a “dour Scot” but he’s got no time for self-repression. As Victoria Azarenka put it, he’s “the realest”.

In this sense Andy is the ideal sporting champion for Scotland – a nation so accustomed to disappointment, at least in a team context, that unmitigated success might trigger an existential crisis. For all his ability, our greatest sportsman is, more than anything, a fighter and a scrapper; a character prone to self-deprecation and self-doubt, who’s been dealt repeated blows only to rise again stronger. Surely no player in history has faced a rockier road to World Number One – but still he got there. If his stirring match against Roberto Bautista Agut was his final stand, then it was an appropriate send-out, fighting back from two sets only to go down bravely in glorious defeat. He’s a winner, but one with an appreciation for our national sporting traditions.

As a Scotland and Raith Rovers fan, my fitba teams will never be involved in the pinnacle of the sport. I watch the World Cup or Champions League finals because I love football, not because I’m deeply invested in the outcome. My earliest memories of Wimbledon are watching Tim Henman – a good player and decent guy, but a figure of that world, a country club golden boy, a cultural avatar for the Home Counties. As well as being Scottish, it felt like Andy could be the lad down the road from you, your friend’s son, that guy you went to uni with. Through this skinny, taciturn teenager from Dunblane, we were vicariously placed centre stage. The sparkling floodlights and dizzying tiers of Flushing Meadows; the regal prestige of SW19’s quintessential England; the bruising tussles in 40 degrees Down Under; exotic settings that were previously in the abstract now took on a thrilling relevance.

When he finally won a Grand Slam at the US Open in 2012, then backed it up at Wimbledon a year later, the talk of Fred Perry and Bunny Austin and Seventy Seven Years felt immaterial. It’s not disrespecting their achievements to observe that those men in trousers rallying leisurely in that grainy, pre-war footage were almost playing a different sport. Murray’s victories were not “the first time since”, they were the first time – the first time after four finals, the first time after all those bitter losses, answering the doubters who said he’d never do it. The waiting was indeed finally over – not for the LTA or Wimbledon, but for himself, his family and his fans, and for his hometown which had suffered like few others.

Most of the memorable moments following his career were collective experiences. On a scorching hot day in July 2013, I gathered with thousands at Festival Square to watch him routinely dismantle Djokovic in straight sets. We all booed when the camera cut to David Cameron and hugged and cheered when Andy sealed the fifth match point, as a passing bus blared its horn. And watching the TV weary-eyed with my family on that windy Sunday night in New York, when he triumphed after five sets and as many hours. Other times were more solitary, perhaps bordering on fanatical, like setting an alarm in the middle of the night to watch some last 16 match at the Australian Open. Or the tradition that developed with friends to have a breakfast fry up while watching his finals in Melbourne. The nights before those matches felt like Christmas Eve, even if after each one the merriment gave way to winter blues.

But perhaps my favourite occasion, at least as pure spectacle, was at the World Tour finals at the O2 arena in 2012. When we bought tickets, we didn’t know which players we’d see, and were excited to discover the first match scheduled was David Ferrer v Juan Martin Del Potro. With perfectly contrasting styles, they played an entertaining three-set match. Watching world class tennis live is always a wonder to behold – and yet when Murray and Djokovic stepped out onto that bright blue court, there was a noticeable step up. The speed, the power, the accuracy, the angles. Nearly every point a classic, with the world numbers one and three near the peak of their powers. The crowd watched transfixed, mesmerised, and rapturous between points, delighting in this moment for posterity, these champions for the ages.

Andy has been a magnificent Ambassador for Scotland but he should now seriously consider his own health and his family. Many of us of a certain age know only too well that severe injuries in early life have a nasty habit of coming back in later years and biting you on the bum.

Think long and hard Andy but whichever way you choose, Good Luck.

It would be wonderful to see Andy as a mentor to the youth of Scotland. An inspirational guy if there ever was one.

Take note, Nicola Sturgeon and John Swinney.

Great read, sums it all up beautifully.

I wish Andy good health and happiness in his life. If he is able to continue playing that would be wonderful for him, and of course all of us who get great pleasure from watching him. Most of all we want him to be pain free.

A perceptive piece of writing by someone who has kept pace with Murray through his career and lived his best and worst moments.

No doubt there will be more great moments ahead whether on the tennis court or not.

Although, of course, a Scotland football team has qualified for the World Cup this summer.