The Ulsterisation of British Politics

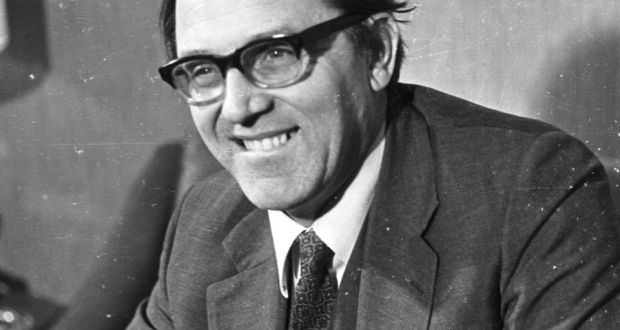

At the height of the Troubles in the 1970s, a new Northern Ireland Secretary named Merlyn Rees introduced a three-part strategy for dealing with the crisis: normalisation, criminalisation; and Ulsterisation. The first part was a straightforward attempt to reduce the level of strife, and above all the death toll, to what a former Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, had earlier controversially described as “an acceptable level of violence”. The second involved the portrayal of the conflict as an internecine law-and-order issue and the ending of special-category status for prisoners, a change that eventually led to the hunger strikes of 1981 and, indirectly, to the reinvention of Sinn Féin as a political force. The third element, Ulsterisation, also known as “the primacy of the police”, was a deliberate policy to reduce the number of casualties from Great Britain at the expense of the locally recruited RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment. The end result of these three policies was to anaesthetise the British public to the horrors of the Troubles and enable the continued prosecution of the Long War against the IRA.

At the height of the Troubles in the 1970s, a new Northern Ireland Secretary named Merlyn Rees introduced a three-part strategy for dealing with the crisis: normalisation, criminalisation; and Ulsterisation. The first part was a straightforward attempt to reduce the level of strife, and above all the death toll, to what a former Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, had earlier controversially described as “an acceptable level of violence”. The second involved the portrayal of the conflict as an internecine law-and-order issue and the ending of special-category status for prisoners, a change that eventually led to the hunger strikes of 1981 and, indirectly, to the reinvention of Sinn Féin as a political force. The third element, Ulsterisation, also known as “the primacy of the police”, was a deliberate policy to reduce the number of casualties from Great Britain at the expense of the locally recruited RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment. The end result of these three policies was to anaesthetise the British public to the horrors of the Troubles and enable the continued prosecution of the Long War against the IRA.

For years the belief has persisted among large swathes of the British public that Northern Ireland is, in Dervla Murphy’s term, “a place apart”, a throwback province neither British nor Irish, addicted to conflict and damned by its own proclivities. Indeed, that is one of the more mainstream readings of the Troubles. That reading of course overlooks both the post-colonial element and the very real parallels with politics elsewhere.

Even leaving to one side the importance of the DUP in propping up the current Conservative Government, the recent emergence of Brexit as the dominant question of British politics has thrown those parallels into sharp focus. Here I shall list a few.

Symbolism Over Reality

Ulster Unionists have sometimes been criticised for what is called “the siege mentality”, the fear that to give ground equals defeat. In Northern Ireland itself, this is sometimes described as “the zero-sum game” — the idea that in any division of a finite pie, more for one side means less for the other. Students of Brexit will recognise a similarity with what economists term “the lump of labour fallacy”, the notion that a job taken by an Eastern European immigrant automatically means an unemployed Brit. In fact, however, the parallels run deeper, for at its most basic level the siege mentality is simply the elevation of symbolism over reality. Nowhere is that more evident than in the DUP’s support for Brexit and ultimately for a hard border.

Needless to say, the prospect of customs posts has not made the Union more secure. In fact, it is fair to say that it has put a united Ireland back on the agenda. That preference for the symbolic or ideal over the tangible and real suffuses the Brexit debate more generally, in which supporters of separation from the European mainland have promoted a policy ostensibly intended to make the United Kingdom richer and more sovereign but which most analyses suggest will have the opposite effect.

Ethnocentrism

Current Northern Ireland Secretary Karen Bradley recently caused a mild furore when she admitted in an interview that she had not known prior to her appointment that Unionists and Nationalists would not vote for each other’s parties, one of the major differences between Northern Ireland on the one hand and Scotland and Wales on the other. In Northern Ireland, for the vast bulk of the population, the ethnic tradition followed is determined by the segregated school system. If British, one votes Unionist or Loyalist, if Irish, Nationalist or Republican. For Protestants in particular, a “journey to Yes” would be unthinkable. And on the Catholic side, where there may always have been a significant minority tolerant of the Union, very few would ever dream of voting for a Unionist politician.

One of the results of this set-up is that parties compete only within their ethnic blocs, with any other political debate taking place at the level of point-scoring or, to use the Northern Ireland term, “whataboutery”. Whether there is a majority overall for a particular course is immaterial. What is important is whether there is a majority within one’s own group. Nowhere was this more apparent than when Ian Paisley claimed that the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, endorsed by 71% of the Northern Ireland population, had been rejected by most Unionists. In fact, given the population structure at the time, that claim was impossible, but in Northern Ireland the rhetoric that he adopted was par for the course.

The current Brexit debacle has been notable for the way in which Scotland and Northern Ireland rejected the proposal. Had Dr. Paisley lived to make a similar claim about a majority of Protestants this time around, it would have been true, for overall only 56% of those in Northern Ireland voted to remain, and voters split largely along ethnic lines. In Scotland, the rejection of Brexit was more emphatic, with 62% voting to stay. Given the very slender majority for Brexit overall in the UK, one might have thought that the UK Government would have had serious doubts about whether to proceed. However, after the 2015 UK general election, the SNP held almost every seat in Scotland. Traditional pan-British parties, which had never figured much in Northern Ireland terms, had been put out of another constituent part of the United Kingdom. They key issue for both Tories and Labour, therefore, was what the voters of England had said, and they had voted to leave. This marked a turning point for the United Kingdom and the mainstreaming of Ulster-style ethnocentrism.

One thing that Scotland and Ulster Unionists have in common is that they were both originally multi-ethnic alliances but are now at an advanced stage of merger. In Scotland, internal ethnic questions have been put to one side, with Gaelic and Scots suppressed in favour of Standard English, religion fast losing importance, and a stylised version of the non-linguistic aspects of Highland culture now symbolic of the entire nation. In Ireland, the term “Protestant”, which had been used to refer to Anglicans alone, recovered its original breadth of meaning when it was extended to take in Presbyterians and Methodists, who for a long time had been classed as “Dissenters”. The fatal design flaw in this promising multi-ethnic alliance, which even picked up the odd Huguenot refugee, was that it was defined not positively but negatively — against Catholicism.

In the modern era, it is fair to say that far too many people in all countries are prone to racism, and Scots have no get-out-of-jail card in that respect. That attacks on ethnic minorities are less frequent in Scotland must to some extent at least be the result of superior political leadership. Something that those living outside Northern Ireland will in all likelihood not be aware of is the recurrent, organised attacks on ethnic minorities by Loyalist paramilitaries over recent years, whether the Chinese, the Poles or the Romanians. There have always been those in Loyalism ready to flirt with the broader extreme right, and many ethnic minorities in Northern Ireland live in working-class Protestant territory — which, reflecting the demographic realities not of today but of the 1960s, is where the empty property is. The morning after the Brexit vote brought similar attacks into the mainstream in England.

Flags

Anyone who has visited Northern Ireland, particularly during the summer months, will have noticed rather a lot of flags on lamp-posts, overwhelmingly British ones, but also the flag of the Northern Ireland Government, paramilitary flags, Scottish and Israeli flags. Irish tricolours feature too, but in different areas and at a lower level. Given that Ulster Unionism, as we have seen, has a highly symbolic culture, all that marking out of territory is perhaps unsurprising. Its elevation of symbolism above reality also explains part of the antipathy to the Irish language and to Irish-language signage in particular — often incongruously articulated by Protestant politicians with Gaelic surnames of Scottish or Irish origin.

Recent years have seen the wholesale rebranding of a host of food British products with Union flags, even where, as in the case of Bell’s whisky, the change seems counter-intuitive and self-defeating. Given that, outside football, there are not usually that many actual British flags seen waving in Scotland, the change has understandably attracted comment. Great Britain differs from Northern Ireland in that the main focus has been supermarket produce, which in Northern Ireland is more likely to be kept neutral; indeed, Empire biscuits are known there as “German biscuits”. In parallel, literally dozens of television programmes have gained the moniker “Great British”. Finally, several Unionist politicians in Scotland have emulated Ulster colleagues in decrying the actually rather half-hearted promotion of the Gaelic language as a “nationalist plot”, with spectacular claims made of exorbitant spending on cost-neutral signage in particular. These developments can be traced to the independence referendum of 2014, of which Brexit itself, in part at least, is a result. If and when Brexit actually happens, British flags will presumably grow only more numerous.

Negotiating with Ourselves

One of the unavoidable results of the ethnic blocs described above is that, with a few notable exceptions, negotiations take place within them, often with the professed aim of achieving ethno-political unity. In Northern Ireland, every election is a referendum on the border, and in first-past-the-post Westminster elections in particular, internal division can mean that the other side wins. The DUP exploited similar fears when they successfully canvassed a change to the Good Friday Agreement so that the leader of the largest Stormont party would automatically become First Minister, calculating that they could now rely on Unionists voting for them in perpetuity rather than splitting the vote and letting in Sinn Féin. The downside of promoting internal unity, on the other hand, is an inability to compromise with the other, to practise politics as the art of the possible. Last week saw the arrival of that phenomenon in Westminster in grand style, with the Conservative Party adopting an incoherent policy obviously unacceptable to its main negotiating partner, the EU, for the purpose of achieving internal party unity. It was duly lauded by the newspapers that gave us Brexit in the first place.

Splitting to the Right

A Northern Ireland politician once commented to me about the relative loyalty of Nationalist politicians — and Sinn Féin ones in particular — to their parties, a major contrast to what he thought was the serial disloyalty shown by Unionists. “Do you know why that is?” he asked. Here I expected him to adduce the serial schisms of Protestantism or, failing that, to infer something from the hierarchical nature of the Catholic Church. “It’s the idols,” he said, taking the conversation to a whole new level of gaga. Between 1920 and the 1960s, the Ulster Unionist Party essentially ran a one-party state, safe from Nationalists because of first-past-the-post voting, the manageably low number of Catholics, the buying of working-class Protestant loyalty through its own form of national preference and, where those wouldn’t work, as in Derry, outright gerrymandering. From the late 1960s onwards, that all began to fall apart. Since that time Unionism has constantly split to the right, most notably when several high-profile politicians left the UUP for the DUP when the former supported the Good Friday Agreement, eventually resulting in a wholesale re-alignment of Unionist politics. Back in the 1980s, when the then Ulster Unionist leader Jim Molyneaux was asked how he fended off the challenge of the DUP’s Ian Paisley, he answered simply, “I out-right him.”

Euroscepticism, from a time long before anyone had ever used the term “Brexit”, has been marked by a similar splitting to the right, albeit at the level of resigning the whip, forcing by-elections, or mounting leadership challenges rather than of setting up a new party. Regardless of what happens with Brexit, it is reasonable to suppose that every future Conservative leader will be looking over his or her shoulder, and on just this issue. Given the huge contradictions in that party, however, it can surely only be a matter of time before much more fundamental change is on the cards.

Paralysis

For many people living in Northern Ireland today, their main political gripe is not sectarianism per se, which after all has always been with us, but the current absence of a Government. If Northern Ireland were a country in its own right, it would now hold the world record for a political vacuum, having surpassed Belgium’s total back in August 2018. Even before the last suspension of the region’s political institutions, however, the Assembly was notable for the very low volume of primary legislation that it passed, a result of its mandatory coalitions and difficulty in finding consensus.

The two and a half years since the Brexit referendum have seen a similar paralysis engulf Westminster. Important issues are not given the attention that they deserve and decisions put on hold, while political discourse is dominated by an overriding constitutional question. In the world of business, too, just as has been the case in Northern Ireland for many years, investment has dried up because of political uncertainty. Even if Brexit is reversed, that investment shortfall will take years to make up.

Conclusion

The near-miss independence referendum of 2014 changed Scotland for ever. Independence now dominates political discourse and will presumably continue to do so until it is achieved. At a UK level the same is true of Brexit, which in addition has let several unpleasant genies out of the bottle. Even if there is no Brexit on this occasion, the prospect will continue to hang over the heads of all those living in the UK — changing and poisoning its politics in the process.

A well written critique of Northern Irish politics.

Unfortunately I’m not sure that it takes us any further forward. Will we see the sensible option of a United Ireland, probably not. Will Scotland hold and win an independence referendum, open to debate but likely to be greatly influenced by unionist propaganda and trumped up charges against Alex and Nicola.

Ireland us a microcosm of the United Kingdom. Entrenched views fed by visceral main Stream Media that it partisan to an extreme. When first I heard the Brexit result I thought, that’ll unite Ireland then I remembered the tribal hatred that trumps any rational argument.

Dougie, the argument is that the Kaffliks will ‘outbreed’ the Proddies, and vote for reunification.

Hence DUP’s determination to smash the GFA.

Just saying, like. Scotland will achieve Self Determination in the aftermath of Brexit, of that there is now no doubt.

I hope you are right.

I enjoyed this article. What is the view now of Irish unification? It is the obvious answer to the British Brexit paralysis.

Northern Ireland is not a province, a province of where? it’s a bit of somebody else’s province!

NO! (or as Maggie once put it: No! No! No!). It is not Ulster. As a person of Ulster but not ‘Northern Ireland’ origin, I must strongly object to the sloppy confusion of the Province of Ulster with the detached bit of the UK. Three of the nine counties of Ulster are in ‘Ireland’.

That hasn’t stopped Unionists falsely adding Ulster to their party name. Once upon a time they used to be Irish Unionists, but that changed, too, didn’t it? Will they make up their mind who they are?

Westminster has no need of NI except as a temporary prop for the May administration.

Had May not stupidly called a snap GE,she would not even have needed that and by now NI would be cast adrift in order to

get her EU deal through Westminster (as she tried to agree with the EU a year past December).

How would the DUP have faired in NI trying to single handedly extract the province from the grip of the EU.

Probably not too well I suspect and they must be thanking their God that a hard Brexit is now on the cards giving them the excuse

to reverse the Belfast Agreement and return to splendid isolation (within the splendidly isolated UK).

Scotland is a whole different kettle of fish,with Westminster’s need to hang onto Scottish resources.

Fortunately they have,for now, a sizeable unionist population who will willing assist in that objective,under the cover of Better Together.

Irish and Scottish unionists are united in ensuring that Westminster continues to rule their province/country but for very different reasons.

Irish unionists I get but Scots ?

The Irish don’t have any oil. The English will ditch Ireland as soon as.

A quick reminder that the majority of Protestants in Northern Ireland are descended from Scottish Presbyterians. Do you remember David Tennant on “Who do you think You are” visiting his long lost cousins in Derry and being presented, to his dismay, with an Orange sash?

This historic but continuing link is probably why many of the more bigoted of them catch ferries from Larne every week to support Rangers rather than going to Liverpool, where they could watch much better football but not enjoy the same sectarian banter that comes with a visit to Ibrox.

The Scottish Tories who opposed T. May’s Plan A did so because of their refusal to countenance the backstop arrangement that would have protected the Irish people from the effects of a hard border. They are just as bad as any English Tory when it comes to putting a huge obstacle in the way of peace, so let’s not have it that “England” is entirely responsible for the situation in Ireland.

Well done to Conall by the way, for pointing out again that Ulster is comprised of nine counties: Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan, Monaghan and Donegal. Not only is Ulster a misnomer for the 6 Counties but so is Northern Ireland, since the most Northerly point of the Irish mainland is in County Donegal, and hence in the “South.”

Very well written.

Excellent piece. Brilliant analysis.