‘Persons in Relation’ – the quality and citizenship agendas in Scotland

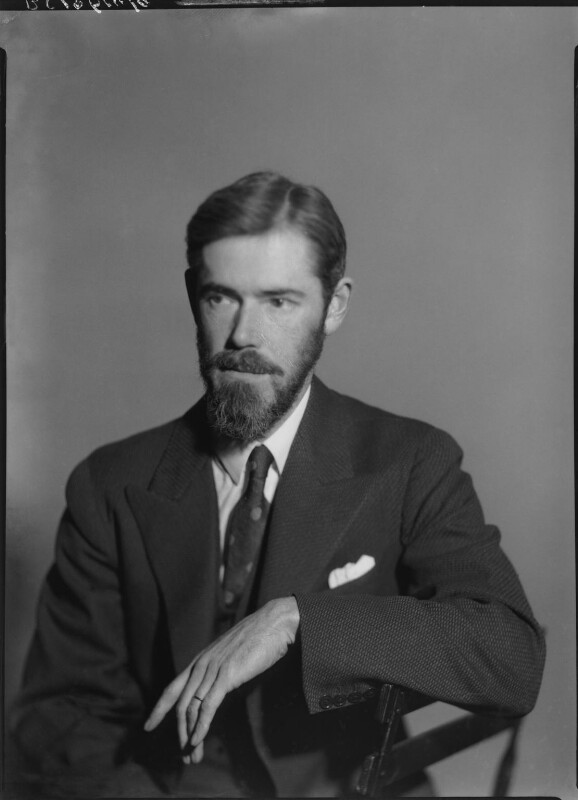

The philosophy of John Macmurray (1891-1976) is only now receiving the attention it deserves. It is in the contemporary climate of dissatisfaction with hyper-individualism that Macmurray’s emphasis on the relations of persons has come to the fore. Moreover, Macmurray’s recognition of the central importance of acknowledging human embodiment is being favourably received by a wide range of fields, which including philosophy, theology and psychology. Macmurray’s overriding concern is to present an adequate account of the person and of personal relationships. Here Colin Kirkwood analyses ‘Persons in Relation’ – and the quality and citizenship agendas in Scotland today in relation to Macmurray’s work.

The philosophy of John Macmurray (1891-1976) is only now receiving the attention it deserves. It is in the contemporary climate of dissatisfaction with hyper-individualism that Macmurray’s emphasis on the relations of persons has come to the fore. Moreover, Macmurray’s recognition of the central importance of acknowledging human embodiment is being favourably received by a wide range of fields, which including philosophy, theology and psychology. Macmurray’s overriding concern is to present an adequate account of the person and of personal relationships. Here Colin Kirkwood analyses ‘Persons in Relation’ – and the quality and citizenship agendas in Scotland today in relation to Macmurray’s work.

I come as a child of the movement for social change that had its gestation in the deep disillusionment that followed the bloodletting and destruction of the first world war, rose to a fullness in the 1942 Beveridge Report which identified five giant evils (squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease), and culminated in the creation of the welfare state: a society of full employment, social security, pensions for all, homes for all, expansion of education at all levels, maternity benefit, family allowances and above all, the National Health Service. A great wave of reform and social creativity supported by the main political parties, which ran for approximately thirty years.

I come as a Scottish generalist, by which I mean that I have never regarded myself as a specialist in any one field, but as someone trying to maintain an overview of a total picture which is always changing, drawing on a number of disciplines including history, language and literature, moral philosophy, adult education, counselling and psychoanalysis.

I come with a continuing commitment to what Paulo Freire called fundamental democratisation, which I consider to be a noble and unfinished cause.

I come with a deep intellectual dissatisfaction which I long to have remedied. Throughout my adult life British culture, British thinking, has been dominated by an entrenched conflict between individualism on the one hand and collectivism on the other. I find this stereotype exasperating and frustrating. It remains a real roadblock to growth and development on these islands. You will not be surprised therefore to learn that it is because John Macmurray addresses this theme directly, illuminates it, and I think resolves it, that he has to be the key figure in this presentation.

But Macmurray does not come to us in isolation. He comes as one member of several communities of persons in relation, and tonight I single out three of those: Ian Suttie, psychiatrist and psychotherapist; Ronald Fairbairn, psychologist and psychoanalyst; and John D Sutherland, Jock Sutherland, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and social visionary, co-founder in 1971 of the Scottish Institute of Human Relations, after whom the Sutherland Trust is named.

One final comment about my orientation. Robert Creeley, one of the outstanding American poets of the 1950s and 60s, wrote a striking line which has haunted me ever since I first read it: “Go forward to get back”. It’s true, of course. But its opposite is also true, a truth we have lost sight of in our progressivist culture – a truth we need to relearn. My formulation is therefore the opposite of Creeley’s. It is: “Go back to move forward”. We need to go back into our personal, communal, intergenerational, historical hinterlands. The past is not what William Shakespeare called “the dark backward and abysm of time”. On the contrary, it is our biological and cultural source, a source of understanding, a source of orientation, a source of what we value and of human figures on whom we can rely, of ideas we can trust, in which we can ground ourselves. Of course, we should not approach our inheritances uncritically, but in a spirit of evaluation, as well as appreciation.

My aim in presenting to you the wisdom of these men is to paint a picture of what the persons in relation perspective means. And having done that, to turn our attention to what it offers us now.

John Macmurray was a philosopher, and a political and cultural activist. His idea of persons in relation is really quite simple. Like a stone dropped in the water, it first makes a splash and then sends out ripples in every direction. He affirms that people are persons, and that their personhood is constituted by their relations with other persons, past and present, conscious and unconscious, inner and outer. With psychoanalysis, he acknowledges that we are capable of repressing our feelings and wishes and thoughts, which nevertheless go on impacting us outwith our awareness. Macmurray challenges us to confront what he calls “unreal” in ourselves, in our feeling and thinking. He argues that we can do that through self-realisation. But his view of self-realisation is the opposite of individualism. It is to be achieved through sincerity and friendship in our mutual relations with other persons. We realise ourselves in, with and for others. Self-realisation is a quality of the relations of persons in community with other persons, which he regards as an end in itself.

Personalism of the kind advocated by Macmurray and Martin Buber is therefore neither individualist nor collectivist. It is simultaneously personal, social and communitarian. It holds that valuable objectives cannot be achieved by habitually subordinating means to ends. The means adopted, as far as possible, must constitute or embody the ends.

Macmurray does not deny that people are objects, or that they can be, and frequently are, treated as objects. A quotation will illustrate his position:

“I can isolate myself from you in intention, so that my relation to you becomes impersonal. In this event, I treat you as an object, refusing the personal relationship.”

Two other aspects of Macmurray’s thinking are relevant. First, his view of knowledge. He argues that there are three kinds of knowledge: knowledge of the inorganic material world; knowledge of the organic, biological world; and knowledge of the world of the personal. He holds that personal knowledge subsumes the inorganic and organic forms of knowledge, and is the highest of the three. This connects with his distinction between “knowledge about” and “knowledge of”. We need both, but they are not identical. “Knowledge about” is intellectual knowledge, based on concepts. “Knowledge of” is direct personal knowledge. It begins with the senses, which we need to cultivate to be fully alive. It involves our emotions which we also need to cultivate. For Macmurray our emotional, sensual and relational life is us. Our emotions are the sources of both our motivations and our evaluations.

But Macmurray is not posing the senses and the emotions against reason. One of his books is entitled Reason and Emotion: he wants us to achieve a new integration of our reason with our emotion, and memorably describes reason as “the capacity to act consciously in terms of the nature of what is not ourselves, whether that be an inanimate object, an organism or another person”.

Macmurray’s philosophy, then, though based on self-realisation, is other-centred rather than self-centred, which is why I personally prefer the phrase ‘persons in relation’ to the adjective ‘person-centred’. His idea of ‘the good other’ is central to his view of personal relations, community, society and religion.

I want now to foreground one other aspect of his thinking. Macmurray is very interested in the deep historical roots of British and European culture. There is a section in his essay on Reality and Freedom headed The Roots of our Culture which reads as follows: “Three old civilisations have been mixed together to form the culture of which we are the heirs: the Hebrew, the Greek and the Roman: a religious; an artistic and scientific; and an organising, administrative civilisation. These three streams of civilisation have never really fused.”

Beginning with this sally, he develops a thesis about the development of European culture out of the Roman imperium. I need to outline this thesis because it helps us to make sense of central tensions in our contemporary culture.

Rome, for Macmurray, is first and foremost an imperial power. It is bent on conquest and rule. Its governing ideal is to establish and maintain an efficient organisation of social life wherever it goes. This is based on law, directive management, the maintenance of power and the defence of property.

Macmurray argues that the Greek arts and the Judaeo-Christian religion were incorporated into, and subordinated within, Roman culture. At the core of the Roman system is duty: obedience to the laws of the state and the law of God. There is a fixed framework of rules for the organisation of life involving rational calculation, the exercise of strong will, and the primacy of policy. Macmurray summarises the key implication of this in the male-dominated language of the time: “a good man will do what he ought to do, not what he wants to do”. In sum, there is a foundational requirement to subordinate emotion to reason, by means of will.

He points out that the dominant philosophy of Rome is Stoicism, whose geographical area of origin is Cilicia, a coastal region of what is now southern Turkey, to the north of the island of Cyprus. This piece of geography is important because Cilicia is the location of the city of Tarsus, where the intellectual founder of Christianity, St. Paul, was born. St. Paul was Saul of Tarsus. Macmurray argues that Paul’s version of Christianity is infused with Stoicism, which is the opposite of the morality preached by the Hebrew prophets and Jesus of Nazareth. According to Macmurray, the tradition represented by the prophets and Jesus is based on an inner vision and an emotional response, not on law and obedience.

So: for Macmurray, the Roman tradition of Stoicism has yoked and distorted the Greek and Hebrew elements. He argues further that these two elements are natural allies against the dominance of rational organisational efficiency. Art and religion, says Macmurray, require a spontaneity of feeling. It is emotion that is the creative force in human experience. I quote: “It is only emotion which can provide the impetus which drives us forward.”

Macmurray now takes us on a fast-forward zoom through the next nineteen and a half centuries, up to his own day. He argues that there have been two great revolts of the Greek and Hebrew elements against Roman dominance. The first of these consists of the artistic/intellectual movement of the Renaissance, and the religious movement of the Protestant Reformation, through the rediscovery of Greek literature and science, and of original Christianity through the study of the New Testament.

He concludes that, while this revolt struck a severe blow at Roman culture, it nevertheless succeeded in re-establishing itself. The net outcomes of this first great revolt of the emotions, according to Macmurray, are the emergence of individualism, and the creation of modern science.

The second great revolt of the emotions is the Romantic Revival, with net impacts like the emergence of the modern democratic state, educational and humanitarian movements, Darwin and evolutionary biology, Karl Marx and socialism. And again, Macmurray asks: did the Romantic movement, led by the poets, succeed in dethroning Roman will and law? Did it release the emotional life from its subservience to rational principles? And again he answers: no, it did not. Roman dominance once again re-established itself, more precariously than before, through a series of compromises, with such net results as:

• the romantic treatment of love

• the sentimentalisation of the moral and social life of Europe, and

• the development of what he calls “the machinery of hypocrisy”.

With that, I conclude my introduction to Macmurray’s perspective. I believe it is profoundly insightful. His thought provides a framework within which we can locate the contributions which follow. One word of caution. It would be wrong to polarise Macmurray’s contribution in terms of a “radicals versus conservatives” stereotype. He is not trying to destroy reason. He is trying to dethrone the Roman imperialist version of it, integrate reason with the senses and the emotions and relocate it with reference to mutuality in human relations. His perspective helps us to make sense of the struggles of the 20th century, and offers us a lens through which to make sense of what is going on in the 21st century.

The Origins of Love and Hate

I turn now to consider the contributions of Ian Suttie, whose work informed Macmurray’s development of his Persons in Relation thesis. If Macmurray is the philosopher of this perspective, Suttie is its psychotherapist. Ian Suttie was a psychiatrist who worked in hospitals in Glasgow, Perth and Fife, and – during the first world war – in what is now Iraq, before moving to London with his wife Jane where they both worked as psychotherapists at the Tavistock Clinic.

Suttie’s work is known mainly to us through his one and only book, The Origins of Love and Hate. He died prematurely very shortly after its publication in 1935. Because of his combative attitude (his work is full of challenges to Freud) his work was greeted with silence by the psychoanalytic establishment of his day.

Suttie’s work is known mainly to us through his one and only book, The Origins of Love and Hate. He died prematurely very shortly after its publication in 1935. Because of his combative attitude (his work is full of challenges to Freud) his work was greeted with silence by the psychoanalytic establishment of his day.

But a number of psychoanalysts were listening to Suttie. John Bowlby unequivocally praised his contribution. He describes Suttie’s book as:

“a robust and lucid statement of a paradigm that now leads the way.”

In selecting a number of Suttie’s themes, I aim to link them with Macmurray’s, because they belong together.

The ground-base of Suttie’s thinking is his postulate of the innate need for companionship from birth. This is embodied in mutual love, tenderness, interest-rapport and fellowship. Suttie rejects Freud’s conception of the infant as a bundle of instincts generating tensions which require discharge, a process in which other persons are needed, if at all, only as means to ends.

Suttie sees the baby as seeking relationships from the start of life, bringing with it the power and will to love, which is met, at best, by the devoted and loving ministrations of its mother or caregiver. This reciprocal love is characterised on both sides by tenderness and appreciation. It is in this interpersonal context that bodily needs arise and are met. There are three vital points here: first, instincts are subordinate to personal relationships; second, love is social and not merely sexual; and third, the interactions between the loving baby and mother are communicative, as well as nurturing.

But Suttie does not idealise love. He understands that things often do not go well. When the baby’s love search is not met, the first result is anxiety, and when this frustration persists, it can generate the reactions of aggression, or of withdrawal.

Suttie’s next key concept is what he calls interest-rapport. He traces the development of the baby’s interest-rapport from the earliest phase of life in which self and other are not yet discriminated. The baby loves its own body, its immediate concerns, its mother’s loving attentions and mother herself. It is in the course of these interactions that interest-rapport develops. As not-self is gradually discriminated, play and fellowship can develop. If things go well, the extension of interest from self-and-mother to other persons and physical objects broadens out to include, potentially, the whole socio-cultural field.

So, love generates interest-rapport which gradually extends beyond and differentiates itself from the original love relationship. With the development of this concept of the growth and spread of interest rapport, Suttie replaces Freud’s concept of aim-inhibited sublimation of the sexual instinct as the explanation for the development of culture, and prepares the ground for the work of Fairbairn, Winnicott, Bowlby, Ainsworth and Trevarthen. He opens the door to interpersonal and socio-cultural perspectives in psychology, psychiatry and psychotherapy, alongside biological and intra-personal perspectives.

I’ve already argued that Suttie does not idealise love. Love can be an equivocal factor in human society. This idea is taken forward in what Suttie calls the development of a social disposition. In this process, Suttie ascribes a crucial role to the emotions, arguing that they are nearly always socially related. For Suttie, the expression of emotion is a means of communication with others and is designed to elicit a response. It aims to keep people in rapport with others, communicates meaning and maintains cooperative association. He argues that the means of emotional communication include the voice, crying, laughter and all kinds of body language. Here he points the way to the work of Trevarthen and Malloch and their collaborators in an important book entitled Communicative Musicality.

For Suttie, love is the primal emotion. All other emotions are interconvertible forms of the urge to love, the conversions deriving their stimulus from changing relationships with the loved person.

We turn now to another vital connection with Macmurray’s thinking, Suttie’s concept of the taboo on tenderness. Suttie holds that the repression of tenderness begins in the process he calls psychic weaning, which relates to physical weaning, the birth of another baby, cleanliness training and the need for the working mother to leave her babies. This can be experienced by the child as a withdrawal of mother’s love, and also as meaning that the child’s love is not welcome to the mother. This thwarting of the child’s tender feelings, grief over the felt loss of mother, and anxiety caused by the apparent change in her attitude, strike at the roots of the child’s sense of security and justice. The child, according to Suttie, is now faced with a number of options: it can develop companionship with others; it can fight for its rights; it can regress; find substitutes for mother; or submit and avoid privation by repression. The last of these options, the repression of longings, is a major source of the taboo on tenderness.

But it is not the only source. Here again, we admire Suttie’s ability to combine interpersonal factors with socio-cultural factors. For Suttie, the taboo on tenderness has its origins in the Roman Stoicism which has pervaded British culture and British Christianity for so long. The child’s parents and older siblings will already, to a greater or lesser extent, be intolerant of tenderness, depending on the degree of stoicism in their own upbringing. As examples of stoicism in British culture, he gives the practice of sending children away from home to attend single sex boarding schools, and the gang of boys who idealise manliness and repudiate any sign of babyishness or girliness. He describes such boys as “a band of brothers united by a common bereavement”.

I call Suttie’s next theme society and the jealousies. Again he is involved in a fierce, one-sided argument with Freud. Freud, so Suttie claims, holds that society is maintained by the dominance of the male leader over his followers. Social behaviour on this view is the result of repression by fear, and the fear involved is the fear of castration. This leads Freud to over-emphasise men’s jealousy of male rivals, and women’s penis-envy of men in general.

Suttie replies that while these factors do exist in certain societies and in certain families, they are not universal as Freud supposes. For Suttie, love is the mainspring of social life. The jealousies disrupt love and frustrate the need for it. The basic unit of society, he argues, is the band of brothers and sisters under the same mother. Mother is the first moraliser, encouraging mutual tolerance by means of fear of loss of love. Freud, Suttie contends, understands only the fear-of-castration factor, not the fear-of-loss-of-love factor. Of these two, Suttie holds, the fear of loss of love is the more powerful.

To Freud’s two jealousies, Suttie adds a version of sibling rivalry, which he calls Cain jealousy; men’s jealousy of women’s childbearing, lactating and nurturing qualities, which he calls Zeus jealousy, and the father’s specific jealousy of the new child produced by the mother, which he calls Laios jealousy. You will remember that Laios was the father of Oedipus who exposed his son on a hillside intending that he should die.

Finally, I want to touch on Suttie’s distinctive view of psychotherapy. He thinks psychotherapy is ultimately about reconciliation, aiming at restoring the love, interest-rapport and fellowship between the alienated self and the social environment. It seeks to overcome the barriers to loving and feeling oneself loved.

The role of the psychotherapist is to offer: “a true and full companionship of interest…the therapist shows by his understanding and insight that he too has suffered…so there is a fellowship of suffering established”. He favours activity and responsiveness on the part of the psychotherapist, and opposes what he calls the fiction of immunity from emotion and the practice of self-witholding. He agrees with Sandor Ferenczi that it is the therapist’s love which heals the patient, and goes on to clarify what he means by love in this context: “a feeling-interest responsiveness, not a goal-inhibited sexuality”. This is not an argument for the therapist using the relationship to meet her own needs. Therapeutic love is altruistic, non-appetitive love, focussing on the suffering and growth of the other. Such a relationship, says Suttie, cannot be self-withholding. The therapist has to be fully present, a real human being, communicating genuine human responses.

I turn now to the third figure in the persons in relation pantheon, the psychoanalyst Ronald Fairbairn, author of Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality. Like Macmurray and Suttie, Fairbairn belongs to a generation born near the end of the 19th century, who came through the first world war and whose studies included philosophy. It was, I believe, this capacity for engaging confidently with ideas which enabled all three of them in very different ways to confront what they inherited. Macmurray’s intellect is formidable and his range of reference is sweeping. Suttie is combative and incisive. Fairbairn is unfailingly courteous and respectful, but no less analytical, no less tenacious.

We already know from Fairbairn’s daughter, Ellinor Fairbairn Birtles, that he and Macmurray knew and admired each other’s work. We know from Harry Guntrip that Fairbairn thought that “Suttie had something really important to say”. But we have had to wait until 2011 to understand exactly what he meant by that.

It was in an issue of the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association published in that year that Graham Clarke’s paper entitled Suttie’s Influence on Fairbairn’s Object Relations Theory was published. What Graham had found in the Special Collections section of the University of Edinburgh Library is Ronald Fairbairn’s own copy of Suttie’s book, The Origins of Love and Hate. Clarke illustrates, in this meticulously researched paper, how the passages in Suttie’s book heavily underlined by Fairbairn correspond closely to the later development of Fairbairn’s own thinking about the dynamic structure of the personality and its rootedness in early relationships. I do not intend to go into detail here, but having read this paper carefully, and being familiar with the writings of both men, I am satisfied that Graham Clarke’s labour of love has enabled us to put a number of missing pieces into the jigsaw, completing our understanding of Fairbairn’s development of what he wanted to call, not object relations theory, but personal relations theory.

I plan to present Fairbairn’s contribution in a slightly unusual way. Where Suttie, in his concept of the development of a social disposition, is concerned with the actual interpersonal impact on the small child of its early relationships, and the interpersonal stance it subsequently adopts, Fairbairn’s aim is to give an account of what he calls the basic inner situation, which gives rise to the child’s way of feeling, construing and relating from then on. Fairbairn’s loyalty to Freud led him to couch his picture in Freudian terms, even though he was actually developing a fundamental critique of Freud’s instinct theory. I am going to take Fairbairn’s summary of his theory, and translate it where possible from latinate language into plain English, but sticking to the meaning Fairbairn intended. You will find his original text on pages 155 and 156 of From Instinct to Self, edited by David Scharff and Ellinor Fairbairn Birtles.

A PERSONAL RELATIONS THEORY OF THE PERSONALITY

(1) The baby is a person, with a sense of ‘I’, from birth.

(2) Love is a function of the baby as a person.

(3) There is no such thing as a death instinct. Aggression is a reaction to frustration or deprivation.

(4) Since love is a function of the person, and aggression is a reaction to frustration, there is no such thing as an ‘id’.

(5) The baby is a person seeking another person to love.

(6) The earliest and original form of anxiety, as experienced by the child, is separation-anxiety.

(7) Taking in the loved other person is a way of coping, adopted by the child, to manage mother insofar as she is unsatisfying.

(8) Taking in the loved other person is not a fantasy of taking something in through your mouth, but a distinct psychological process.

(9) Two aspects of the loved other person are taken in: an exciting aspect, and a frustrating aspect. They are split off from the core of the loved other, and pushed out of awareness.

(10) These two repressed aspects of the loved other (the exciting and rejecting aspects) now exist inside the person.

(11) The main core of the loved other person is not repressed, but idealised.

(12) The exciting and rejecting aspects of the loved other person previously existed in relationships with the child’s self. So now, two aspects of the child’s self are also pushed out of awareness, along with the exciting and rejecting aspects of the loved other, to which they are still attached.

(13) The resulting inner situation consists now of three distinct aspects of the person, in relation to three distinct aspects of the loved other, as follows:

(a) a conscious self relating to an ideal other

(b) a repressed needy self relating to an exciting other

(c) a repressed rejected self relating to a rejecting other.

(14) This picture of the inner situation represents a basic divided self, or divided person, more fundamental than Melanie Klein’s depressive position.

(15) The rejected self, because of its experience at the hands of the rejecting other, takes up a hostile attitude towards the needy self. It passes on the rejection. This attitude reinforces the repression of the needy self by the conscious self.

(16) What Strachey’s translation of Freud calls the ‘superego’ is really a combination of the ideal other, the rejected self, and the rejecting other.

(17) This is a way of seeing the human personality in terms of internalised self-other relationships, rather than one based on instincts.

My translation of Fairbairn’s summary of his personal relations theory clearly connects with Suttie’s account of the development of a social disposition, the difference between them being that Suttie’s account is couched in terms of attitudes to actual social relationships, whereas Fairbairn’s summary refers to the existence of internal representations of aspects of the self, aspects of the other, and of their relationships. I argue that there is a really close relationship between the social disposition and the basic inner situation: the intrapersonal reflects the interpersonal, and the interpersonal reflects the intrapersonal.

When we read Jock Sutherland’s account of Ronald Fairbairn’s own development, in his book Fairbairn’s Journey Into the Interior, we can see that Fairbairn himself grew up in a patriarchal, stoical culture, and as a result became a somewhat reserved and inhibited man. In these respects he was like many of his fellow Scots of that period. These qualities were reflected initially at least in his approach to the conduct of psychoanalysis. He sat behind a large desk with his patient on a couch on the other side of the desk, facing away from him. As his practice developed and his understanding of self and other deepened, Fairbairn moved away from this distancing practice towards a closer and more dialogical relationship. This suggests that the mid 20th century view of the psychoanalytic relationship with its distancing, self-withholding, blank screen qualities was at least partly a reflection of the stoic culture of British society as of anything inherent in the psychotherapeutic relationship. In line with these developments, our fourth key figure, Jock Sutherland, argues for a warmer and more spontaneous psychotherapeutic style.

Sutherland was a remarkable person. When he came to meet our cohort of psychoanalytic psychotherapy trainees in 1990, one of our group immediately dubbed him “gentleman Jock” and that did not feel unfair. But there was nothing condescending about Sutherland. He spoke to you directly in a friendly way, wanted to hear your response and was genuinely interested in it. Sutherland was born in 1905, studied psychology and psychiatry, and had an analysis and lifelong friendship with Fairbairn. He trained as a psychoanalyst, played a leading role in the War Office Officer Selection system, and for twenty years was head of the Tavistock Clinic in London. He was a member of the middle or independent group of analysts, and the people he admired most were Fairbairn, Winnicott, Guntrip and Balint. He was editor of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and of the British Journal of Medical Psychology. He had a significant influence also on the development of psychoanalysis in the United States of America.

For our purposes this evening, his focal achievement is his co-founding of the Scottish Institute of Human Relations. The word ‘co-founding’ is important because although Sutherland was an inspiring leader and communicator, he was at the same time an enabler and collaborator, interested in others, promoting and supporting others, making connections across disciplinary boundaries and able to operate at all levels of society.

We need to acknowledge also that Sutherland is a transitional figure. The Scotland to which he returned at the end of the 1960s was still a patriarchal and misogynist society, a society in social, economic and cultural turmoil. Political power was passing from the Conservatives to Labour, there was a rising Scottish National Party, a tiny but influential Communist Party, and a small but not insignificant Liberal Party. The golden age of the 1950s and 60s was coming to an end, running aground on the rocks of growing unemployment and government debt. The discovery of oil in the North Sea was just round the corner. Popular hopes for achieving a socially and economically just society were as high as ever. Deference was declining. There were significant trade union, religious, self-management, community action and feminist movements.

Into this environment came Sutherland with the energy of a 21 year old and the vision of a prophet. It would be inaccurate to imagine that he came north to establish psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic training, in the narrow sense of four or five times a week treatment in private practice. He valued that tradition highly, but understood that on its own it was not in tune with the nature of Scottish culture. His aim was to spread psychoanalytic ideas and practices throughout Scotland, beyond the couch, through the professions, institutions and communities of Scotland, in dialogue with people at all levels of Scottish society who were already active and innovative. He made creative connections with psychiatry, psychology, nursing, general practice, occupational therapy, social work, the clergy, education, particularly list D schools, and adult and continuing education. He promoted community development, community mental health and counselling. There are people here tonight who took part in hugely influential groups which were one of the hallmarks of the work of the Institute in the 1970s. He promoted women and young people, people from the so-called lower professions as much as the so-called higher professions.

The achievements of the SIHR can be summarised as follows: the importance of groups; the establishment of a training in analytical (later psychoanalytical) psychotherapy; the establishment of the human relations and counselling course; the development of consultancy to many kinds of organisations; the development of child and adolescent psychotherapy and training; and family therapy.

Two of its early objectives have not yet been fully achieved: to establish psychoanalytic/psychodynamic perspectives and practices across the NHS, and within the Universities. This is a story of considerable partial success, rather than failure. Most recently, the Institute’s successor body, Human Development Scotland, after a successful competitive bid, has been fully funded by NES (National Health Service Education Scotland) to deliver a second programme of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training in Scotland. This includes a significant increase in central funding, carrying a big message about serious investment. Additionally, a commitment to increase access to child psychotherapy is now official Scottish Government policy. As a former Board member of SIHR and as a member of Human Development Scotland, I welcome these new developments. I hope they will be the first of many.

I want to take this opportunity to float a new proposal. I believe that Sutherland’s strategic reading of Scottish society was essentially correct, but that it needs to be updated and reinvented to meet the needs of the Scottish community in the 21st century. When Sutherland was Head of the Tavistock Clinic (now the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust, and a fully integral part of the NHS in England) he was concerned to achieve a broad integration. One to one psychoanalytic work was done very early in the morning, often starting at 6 am, and was regarded by him and his colleagues as a valuable form of research. But the bulk of the psychoanalytic contribution within the NHS then took the form of a wide range of group work.

Things have moved on since those days. At UK level, we now have specialisms and separate institutions for psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic psychotherapy, group analysis, family therapy, child and adolescent psychotherapy, couple psychotherapy, counselling, and organisational consultancy.

It is my contention that specialisation has gone too far and become counter-productive. This reflects to some extent the individualist culture that has come to be associated with Thatcherism. That association may be unfair to Margaret Thatcher, who has been out of office for over twenty years and is no longer with us. It is not Margaret Thatcher, but ourselves, who have become self-centred and narrowly self-interested. To me, this is the central problematic of contemporary culture, a problematic that the psychoanalytic traditions and the persons in relation perspective can help us to tackle.

My proposal is that we learn anew from the thinking behind the Institute’s Human Relations and Counselling Course in the 1980s and 90s. It was a generic programme tailored for that period. We cannot replicate it now. But we could profitably carry out an assessment of the mental health needs of adults, children and families in the Scottish community today. What problems are of greatest concern? How can they be addressed most effectively? What insights and practices will be most helpful? How can we adapt our psychoanalytic inheritances to meet today’s needs?

I propose that Human Development Scotland, in partnership with the Sutherland Trust, the NHS in Scotland and its education arm, NES, and other stakeholders, establish a working group to address these questions with a view to recommending specific courses of action: in particular to make a recommendation as to the most effective form of training of psychoanalytically and relationally informed practitioners in all specialisms in Scotland; and a recommendation also as to the best forms of employment and deployment of these practitioners in the public and voluntary sectors in Scotland. The grain of Scottish culture and ethics suggests that what is worthwhile must be made available to all who need it, not only to those who can afford to pay for it privately.

What we will discover, I believe, is that there is a need for relational psychotherapists working in psychiatric wards and other public and voluntary sector settings, who can combine competence in one-to-one psychotherapeutic work with individuals once or twice a week, with group work, family work, couple work and organisational work. The most pressing and widespread needs in Scotland today are to be found in adults and adolescents suffering from eating disorders, from alcohol and drug related problems, from the epidemic of family and relationship breakdown, from internet-and-media-related addictions, obsessions and sexual abuse, and from depression and loss of self-esteem.

We need a new generic programme of training, incorporating elements of one to one, group, couple, family, and organisational work. Some of these elements would be core, and some optional.

Such a psychoanalytic/relational programme would fit between currently existing programmes of counselling training on the one hand, and psychoanalytic psychotherapy training on the other. There is a strong case for incorporating all of these trainings into a common framework, with a variety of entry points, pathways and choices, and a number of possible exit points. Such a development will reinvigorate psychoanalytically and relationally informed training in Scotland, and dramatically increase throughput of students at all levels.

Such a programme should be explicitly pluralist and dialogical, avoiding the temptation to promote one underlying perspective.

It will be vital, in promoting such an initiative, that Human Development Scotland works in full partnership with the NHS and NES, existing producer/trainer/trainee interests (APTC AND SAPP), appropriate Universities with experience of combining professional training with academic study and the development of research capabilities. Such a programme would allow participants to graduate with professional qualifications and, if they choose, also with Masters and Clinical Doctoral qualifications. The centre of gravity should lie in the development of generic professional capabilities, and the adaptation of psychoanalytically and relationally derived insights and practices to meet contemporary needs in public and voluntary, as well as private, sector settings.

I want to turn, finally, to address concerns arising throughout the UK, in the NHS and other settings, which highlight issues of quality and citizenship. Our intention in formulating the title of this Sutherland Trust lecture was to communicate the idea that the persons in relation perspective might be the key to tackling questions of quality and citizenship in contemporary Scotland and beyond. Our problems have an ethical core, whatever their epiphenomena might be.

Our society has gone through enormous transformations in the last sixty years. New trends are rampant. New problems have emerged. Many of the changes derive from technological advances. Others reflect increases in the scale of governance, as centres of power have moved further away from persons and localities. Others again have to do with the eruption of libertarianism which has accompanied the decline of deference.

It is interesting to note that of all the initiatives taken to implement the reforms advocated by the Beveridge Report, it is the National Health Service which continues to be held in highest esteem. It is to challenges recently emerging in the NHS that we now turn.

I have selected three recent documents to discuss. First, an overarching policy document published by the Scottish Government in 2010 entitled The Healthcare Quality Strategy for NHS Scotland. Second, the Report by Robert Francis on the failings of the Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. And third, the Investigation into Management Culture in NHS Lothian. It is fascinating to note the degree to which, just as the emerging aspirations are shared, so also the emerging problems have features in common.

If we examine the Scottish Government’s policy document, we note that its core message is that all health services should be delivered with a view to their safety, their effectiveness and their person-centredness. The safety focus is a response to such issues as healthcare associated infections and avoidable hospital deaths. The focus on effectiveness concerns primary prevention, early intervention, evidence-based care, well-trained and empowered staff working in multi-disciplinary teams, and optimal use of existing and new technologies. The focus on person-centredness counterbalances these two, addressing fears that some services may at times appear to meet the needs of professionals rather than those of patients; and that some professionals may be overly focussed on the technology of treatment, and may have lost sight of the need to offer patients an empathic encounter and response, thus ensuring that treatments are tailored to patients’ perceived experiences as well as to their objective conditions.

The use of the term “quality” in this report is significant, because it highlights the qualities of persons as well as the qualities of things.

In the Francis Report, the author diagnoses a whole system failure. A core concern is the neglect, abuse and death of elderly patients in the hospital’s care. On the positive side, he calls for a reaffirmation of what is important, and what he means by that is:

• commitment to common values

• readily accessible fundamental standards

• zero-tolerance of non-compliance

• strong leadership

• and equal accountability of all staff at all levels.

In the most recent document, an Investigation into Management Culture in NHS Lothian, the kernel of concern is the suppression of information about patient waiting times for treatment, but the focus of analysis is placed less on system and more on culture, which is defined as shared values and beliefs about what is important. The report argues that behaviours, feelings and relationships are what matter, and that these need to be shared across the whole organisation and reflected in daily practice.

It goes on to contrast NHS Lothian’s aspirational values with what it describes as an oppressive management style characterised by bullying. The solution proposed is a change in leadership style: more collegiate, with strong accountability and zero tolerance. There is a call for a programme to create ownership of avowed values and behaviours, to be embedded in the organisation through training and induction programmes. Managers are to be clear about the distinction between bullying and firm management. And finally, “the Board should develop an open learning organisation rather than one based on blame”. Shades of Jock Sutherland!

If we try to characterise these problems and aspirations, which are replicated across most if not all sectors of contemporary society, what stands out is the feeling that the good aspirations are there all right, but something difficult to pin down is getting in the way, sabotaging their implementation. I find myself remembering three things: first, the successful series of conferences run by Marie Kane, on behalf of the Scottish Institute of Human Relations, entitled Working Below the Surface. Marie has put her finger on a key theme affecting every sector of organisational and institutional life. Second, I find myself remembering Jock Sutherland’s insistence that the main contribution of psychoanalysis to the NHS should be to provide a range of high quality learning experiences in groups. It is in interpersonal explorations in groups that what is going on above and below the surface can be brought into creative contact.

But there is a third set of factors at play in our institutions, factors already on the surface and running rampant. Individualism. Self-interest. Greed. Untrammelled ambition. Ruthless acquisitiveness. Dramatic increases in income inequality. Alarmingly risk-taking capital accumulation. An intensity of narcissism that puts Narcissus himself in the shade.

What these factors are undermining is ordinary altruism, continuity of going-on-doing good-enough work, the sense of a genuinely shared project, the idea of social justice as something more than a platitude mouthed by politicians and commentators.

People are entitled to a stake in society and community, which has to include useful work they can do, a living wage they can actually live on, enough access to resources and support to enable them to engage in learning throughout their lives, the communal reaffirmation of shared values and ways of living, and regular healthy exercise. That used to be called sport, before it got confused with intense competition and big money-making.

If Scotland and other parts of the UK become self-governing, as I hope – and you’ll notice that I said self-governing rather than independent – then I see the NHS as a great potential vehicle for developing what that middle letter H stands for: HEALTH, meaning more than the treatment of illness, prescribing and providing opportunities for cycling, swimming and walking; learning about self, other and relationships in groups; and accessing individual, couple and family work when there are difficult problems to be tackled, not because they are seen as deficient, but because as the great English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott put it: life is inherently difficult for every single one of us.

We need to reverse the dynamics of centralisation and the objectification of persons, and replace them with personal and community empowerment. We need to combine enlightened self-interest with other-centredness in a renewed altruism, and re-affirm the self-realisation in, with and for others which John Macmurray proclaimed as the key to the good society.

*

from the Sutherland Trust Lecture Edinburgh

Thanks for this comprehensive material, Colin. I cannot contribute to the psychotherapy component, but I will venture a few remarks regarding your description of John Macmurray’s philosophy. I do this not in any spirit of contradiction or argumentation, but simply as an expansion on matters of common interest. Many more correspondences could be explored, not least: ‘[Macmurray’s] distinction between “knowledge about” and “knowledge of”’, and: “Personalism of the kind advocated by Macmurray and Martin Buber is therefore neither individualist nor collectivist. It is simultaneously personal, social and communitarian.”. But this post will end up more than long enough even with my restricted focus.

John Macmurray (1891-1976)

Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977)

I was interested that John Macmurray was a Christian. I have an abiding preoccupation with the work of another Christian philosopher, Herman Dooyeweerd. I notice that the dates of both thinkers are remarkably close. Many questions addressed in Macmurray’s thought also arise with Dooyeweerd. For example, you write:

“Macmurray is very interested in the deep historical roots of British and European culture. There is a section in his essay on Reality and Freedom headed The Roots of our Culture…”

Coincidentally, Dooyeweerd has a book entitled ‘Roots of Western Culture: Pagan, Secular, and Christian Options’.

You also write:

“Macmurray argues that Paul’s version of Christianity is infused with Stoicism, which is the opposite of the morality preached by the Hebrew prophets and Jesus of Nazareth. According to Macmurray, the tradition represented by the prophets and Jesus is based on an inner vision and an emotional response, not on law and obedience. So: for Macmurray, the Roman tradition of Stoicism has yoked and distorted the Greek and Hebrew elements.”

Thirdly, the following paragraph by you (which strikes me as both insightful and inspiringly brave given the current “right-side-of-history” dogma):

‘One final comment about my orientation. Robert Creeley, one of the outstanding American poets of the 1950s and 60s, wrote a striking line which has haunted me ever since I first read it: “Go forward to get back”. It’s true, of course. But its opposite is also true, a truth we have lost sight of in our progressivist culture – a truth we need to relearn. My formulation is therefore the opposite of Creeley’s. It is: “Go back to move forward”. We need to go back into our personal, communal, intergenerational, historical hinterlands. The past is not what William Shakespeare called “the dark backward and abysm of time”. On the contrary, it is our biological and cultural source, a source of understanding, a source of orientation, a source of what we value and of human figures on whom we can rely, of ideas we can trust, in which we can ground ourselves. Of course, we should not approach our inheritances uncritically, but in a spirit of evaluation, as well as appreciation.’

In this post, therefore, I limit myself to a few Dooyeweerd quotes regarding the foregoing identified issues, namely the roots of European thought and the place of Stoicism. At least implicit in these is Dooyeweerd’s deep interest (elaborated elsewhere in his writings) in what he has called ‘The Criteria of Progressive and Reactionary Tendencies in History’.

GROUND-MOTIVES

A key to Dooyeweerd’s analysis of western thought is his account of dualistic “ground-motives”. These are not propositional or philosophical premises or stances, but in fact precede and predetemine the latter as far more deep-seated, typically unperceived, cultural defaults. Despite postmodernism, there remains a prevailing hubris about neutrality and objectivity. The theoretical thought of any society must therefore be sounded for pre-theoretical “ground-motives”. Dooyeweerd uses the (no doubt entirely unhelpful) term “religious” to descibe these. It must be constantly reiterated that he is not in the slightest referring thereby to “organised religions”, but rather to the search for ultimate personal or communal concentration-points of ontical meaning, which restless yearning is a structural dynamic of humans per se.

Regarding ground-motives, Dooyeweerd writes:

“‘The religious ground-motives in the development of Western civilization are basically the following:

1. The “form-matter” ground-motive of Greek antiquity in alliance with the Roman power motive (‘imperium’).

2. The Scriptural ground-motive of the Christian religion: creation, fall, and redemption through Jesus Christ in communion with the Holy Spirit.

3. The Roman Catholic [Thomistic] ground-motive of “nature-grace”, which seeks to combine the two mentioned above.

4. The modern humanistic ground-motive of “nature-freedom”, in which an attempt is made to bring the three previous motives to a religious [ultimate] synthesis concentrated upon the value of human personality.'”

(Herman Dooyeweerd, Roots of Western Culture: Pagan, Secular, and Christian Options, Paideia Press, 2012, p15)

STOICISM

Regarding Stoicism, Dooyeweerd writes:

“The ideas of world citizenship and of the natural equality of all human beings were launched considerably later in Greek philosophy by the Cynics and the Stoics. These ideas were not of Greek origin. They were essentially hostile to the Greek idea of the state, and they exerted little influence on it. The radical wing of the Sophists was similarly antagonistic. Guided by the Greek matter motive, it declared war on the city-state. Even more radically foreign to the classical Greek was the Christian confession that the religious [ie ultimate] root-community of humankind transcends the boundaries of race and nation. The Greek ideal of democracy that emerged victorious in Ionian culture was quite different from the democratic ideal of modern humanism. Democracy in Greece was limited to a small number of “free citizens.” Over against them stood a mass of slaves and city dwellers with no rights. […] The Greek idea of the state, however, was basically totalitarian. (Roots p 21)

“Stoic philosophy (influenced by Semitic thought) had introduced into Greek thought the idea of the natural freedom and equality of all human beings. It had broken with the narrow boundaries of the ‘polis’. The founders of Stoic philosophy lived during the period when Greek culture became a world culture under the Macedonian empire. Their thinking about natural law, however, was not determined by the religious [ie ultimate] idea of ‘imperium’ but by the old idea of a so-called golden age. This age, an age without slavery or war and without distinction between Greek and barbarian, had been lost by humankind because of its guilt. The Stoic doctrine of an absolute natural law reached back to this pre-historic golden era. For the Stoics, all people were free and equal before the law of nature.

The Roman jurists based the ‘ius gentium’ [‘law of nations’] as a private world law on this ‘ius naturale’ [‘natural law’]. In doing so, they made an outstanding discovery. They discovered the enduring principles that lie at the basis of civil law according to its own nature: civil freedom and equality of human beings as such… As one would put it today, civil law is founded on human rights. The Roman ‘ius gentium’ [‘law of nations’], which still legitimized slavery, actualized these principles only in part, but the doctrine of the ‘ius naturale’ [‘natural law’] kept the pure principles of civil law alive in the consciousness of the Roman jurists.

At the close of the Middle Ages most of the Germanic countries of continental Europe adopted this Roman law as a supplement to indigenous law. It thus became a lasting influence on the development of western law. The fact that national socialism resisted this influence and proclaimed the return to German folk law in its myth of ‘blood and soil,’ only proves the reactionary character of the Hitler regime. It failed to see that the authentic meaning of civil law acts as a counterforce to the overpowering pressure of the community on the private freedom of the individual person. But the process of undermining civil law, which is still with us, began long before national socialism arose.” (Roots 26, 27)

Dooyeweerd is of course not uncritical of Stoicism:

“Neither a nation, nor the Church in the sense of a temporal institution, nor the State, nor an international union of whatever typical character, can be the all-inclusive totality of human social life, because humankind in its spiritual root transcends the temporal order with its diversity of social structures.

This was the firm starting-point from which Christianity by the spiritual power of its divine Master broke through the pagan totalitarian view of the Roman empire, and cleared the way for a veritable and salutary revolution of the social world-view. The radical meaning of this Christian revolution would be frustrated by identifying it with the Stoic idea of humankind as a temporal community of all-inclusive character. It is true that the natural law doctrine of Hugo Grotius used this Stoic idea as a foundation for international law and that this idea broke through the classical Greek absolutization of the ‘polis’. But it could never become the starting-point for a social world-view which hits any absolutization of temporal societal life at its roots. It could not clear the way for a theoretical examination of the basic structures of individuality determining the inner nature of the different types of societal relationships. […] The Stoic idea of natural law in principle broke through the classical Greek idea of the city-State as the perfect natural community. It proclaimed the natural freedom and equality of all humans as such. It is true that the Roman ‘ius gentium’ [‘law of nations’] did not entirely satisfy these principles of freedom and equality, insofar as it maintained slavery; nevertheless, it constituted an inter-individual legal sphere in which every free person was equally recognized as a legal subject independent of all specific communal bonds, even independent of Roman citizenship. This was the fundamental difference between the undifferentiated Quiritian tribal law and the private common law.” (A New Critique of Theoretical Thought, Vol III, p 169, 447)

PROGRESSIVE AND REACTIONARY TENDENCIES IN HISTORY

As hinted at previously, Dooyeweerd lived through the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. As an important part of ‘Roots of Western Culture’ (originally written as a long series of Dutch newspaper articles in the aftermath of the 2nd World War), he traced the philosophical origins of Nazism:

“We have witnessed the unspeakably bloody and reactionary regime of nazism, the degenerate spiritual offspring of modern historicism. Totalitarian “racial” [volkse] ideals, inspired by the myth of “blood and soil,” reverted western culture to the dark night of the pagan nature religions. Moreover, these totalitarian ideals were backed by the military power of a mighty modern state. […] Science and art, child rearing and education, industry and technology, labour organizations and philanthropy – all were made subservient. […] Following the example of the mathematical and natural sciences, earlier humanistic theory had always searched for the universally valid laws that control reality. It constructed an “eternal order of natural law” out of the “rational nature of humankind.” This order was totally independent of historical development, and was valid for every nation at all times and in all places. […] But as a result of the polarity of its religious [ultimate] ground-motive, humanism veered to the other extreme after the French Revolution. Rationalistic humanism (in its view of mathematics and modern natural science) turned into irrationalistic humanism, which rejected all universally valid laws and order. It elevated individual potential to the status of law. […] When the Historical School attempted to understand the entire culture, language, art, jurisprudence, and the economic and social orders in terms of the historical development of an individual national spirit, it elevated the national character to the status of the origin of all order. […] Historicism robs us of our belief in abiding standards […] If everything is in historical flux and if the stability of principles is a figment of the imagination, then why prefer an ideology of human rights to the ideals of a strong race and its bond to the German soil?” (Herman Dooyeweerd, ‘Roots of Western Culture: Pagan, Secular, and Christian Options’, Paideia Press, 2012, pp 52, 63, 74, 87)

Let me finish by providing a URL for anyone interested in downloading free pdfs of Dooyeweerd books:

https://hermandooyeweerd.wordpress.com

‘Roots of Western Culture’ appears as third book down under the heading: “Series ‘B’ (essay collections)”. 256 page pdf download.