Looping the Thread

One of the most enduring sounds from my childhood was the drone of my grandmother’s Singer sewing machine. As I sat watching the television, I’d be dimly aware of the comfortable hum of the needle coming from the ‘wee’ bedroom of her council house, where she sat surrounded by pincushions and thimbles, scissors and safety pins, and folds of material waiting to be transformed into clothes, costumes and furnishings.

One of the most enduring sounds from my childhood was the drone of my grandmother’s Singer sewing machine. As I sat watching the television, I’d be dimly aware of the comfortable hum of the needle coming from the ‘wee’ bedroom of her council house, where she sat surrounded by pincushions and thimbles, scissors and safety pins, and folds of material waiting to be transformed into clothes, costumes and furnishings.

It was my grandmother who designed and stitched my mother’s wedding dress and her bridesmaids’ dresses, as well as the pink and blue suit she wore as mother of the bride. Never one to throw away what could be salvaged, the wedding dress was later transformed into my baptismal gown and, even smaller pieces of material, into tiny satin ballgowns for the Barbie dolls my sister and I played with. It is only now, looking back at old photographs, that I realise the incredible skill that went into my grandmother, Dorli’s, creations. She made fancy dress costumes for us on Hallowe’en, and for the Lilias Day Parades in Kilbarchan where we lived, including a ladybird with bobbing antennae, and a very cute snowdrop outfit I had complete with white cap and green leggings.

Yet her talent went largely unrecognised. Like many women of the war generation, self-sufficiency was something of a necessity and she had what almost amounted to an aversion to buying new clothes (she’d even tear up my grandfather’s old pyjamas to use as cloths). Yet Dorli had a creative flair that, had she been born in a different era, might have been nurtured by a university course in art or design. But such ambitions were rare amongst women of her generation and social class. She came from rural Europe, a small town called Gratkorn, near the city of Graz, in Austria. My grandfather was from Elderslie, Renfrewshire, the apparent birthplace of William Wallace. Theirs was a war romance, then he brought her over to Renfrewshire and the rest, as they say, is family history.

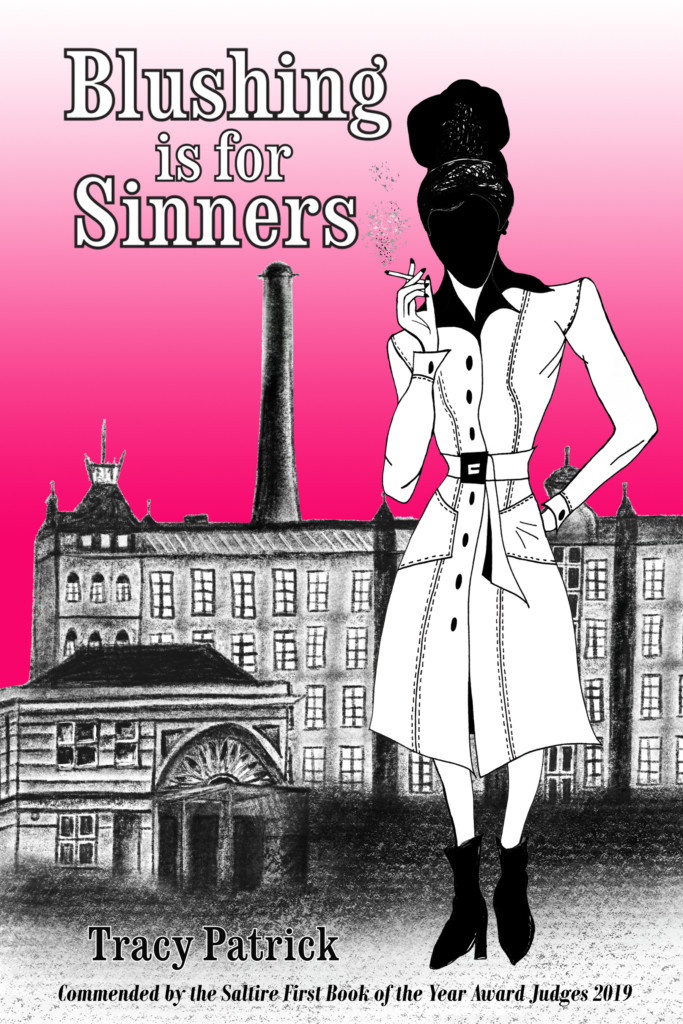

I won’t go into the inevitable Nazi insults hurled at her as a result of her Austrian accent. She changed her name to Doris, and learned English slowly and by ear, piecing together nouns, verbs and sentences. Her favourite novel was Pride and Prejudice, which she read faithfully, over and over. Sadly, Dorli died before my first novel, Blushing is for Sinners, was published, so I’ll never know what she would have made of the story of Jean, a Paisley mill worker who longs for a better future; and her daughter, Ava, who ends up growing up without her mother in a different country, Canada. Yet, somehow, it seemed natural that I should dedicate the novel to Doris. Jean is a romantic dreamer who falls in love with the wrong man and, as the contrast between her fantasy world and her reality becomes increasingly bleak, she embarks on a drastic course of action.

I have read some of the letters Dorli wrote to my grandfather after he was demobbed, and while she was waiting to be brought to Scotland. They are tender and filled with a young person’s ideal expressions of love. The reality of finding herself in a council flat in a grim Scottish industrial town with two small children to bring up must have brought a certain amount of disillusionment to a romantic soul who dreamed of the Hapsburg empire and grand opera houses of Vienna.

I remember going with my grandfather on Friday afternoons to collect my grandmother from the Chrysler car plant where she worked, and watching hundreds of women pour from the factory and out onto the street. Like the mill girls, my grandmother belonged to a generation of women who thrived on the camaraderie that enabled them to survive years of repetitive piece work. She once lost her wedding ring in a box of car parts only to have the team at the other end take the trouble to find it and return it to her. In my novel, Jean’s mother, Senga, and her friends, Maggie, Isa, and the no-nonsense ‘Big Una’ are reminiscent of this generation, the lifelong friendships they formed, and the small kindnesses they showed to each other that shone a light through the dark times. On finding out the mills will no longer be offering long-service certificates, Una says: ‘It’s a sign. It’ll be just like the end a the trams, only naebody’ll be lining the streets tae wave us goodbye.’ Similarly, Jean recalls how, on her mother’s last day at the mills: ‘the front room was filled with flowers and all the women she worked with came round for sandwiches, cake and tea. After they left she cried like somebody had died, like it was a funeral.’

By the time I was at school, this way of life had already disappeared. I remember passing the Ferguslie mills on the bus every morning, the buildings like old vanguards of days gone by. They were outdated institutions, something to be rebelled against, like the ‘daft old guy in war medals’ who chases Jean’s loud-mouthed boyfriend, Billy, round the cenotaph. It is Billy, who, in his unflattering way, senses the transitory nature of industry: ‘One day, nane a this will exist. All gone, like cardboard in the rain.’ Nowadays there is an element of nostalgia about the mills: the social activities and educational classes; the holiday outings; the medical care they provided to women when there was no NHS; the detailed architecture. Indeed, the Coats and Anchor labels would have been familiar to Dorli whose own mother swore by the quality of the thread. Back then, living in Paisley was something to write home about.

By contrast, Jean’s daughter, Ava, has opportunities afforded to her that women of older generations lacked. Perhaps the geographical distance between mother and daughter in the story is somewhat symbolic of the distance between myself and Dorli, an intensely private and serious woman who, no doubt for her own reasons, did not reveal much about her inner life. It is only when it is too late, I realise there was so much about her I didn’t know. The quiet hum of the Singer always blended into the background, behind the TV and chatter. It was only when it finally stopped that I really began to listen. My grandmother’s roots belong to me too and, like Ava’s son, Scott, who is fighting to protect the old growth trees of British Columbia from logging, dedicating this book to my grandmother is a way of exercising some kind of guardianship over her memory and over our shared history.

I have one of her boxes of thread at home, dating from the sixties and bearing the distinctive Coats logo. Inside is a mosaic of colours: sungold; air force blue; glowing pink; artillery red; wood violet. It was Dorli’s black cotton thread that I used to hand-stitch copies of my poetry pamphlets a few years back. Her mother was right; the thread is still strong and sturdy as ever, its quality undiminished.

A fine example of the great writing you include here by via the multidimensional subject matter that forms your literary quilt. Or should I say tartan?

Can I thank you for publishing this, as it took me straight back to 32 Hawthorn Street in North Kilbowie in Clydebank, where in the front bedroom, my gran kept her treadle sewing machine, made of course by Singer. On this machine she made clothes not just for the family but for clients who would come up for fitting. Not exactly Saville Row, but the best many people could afford, and there were some occasions when, having finished a job, knowing the client would have struggled to pay, she would say “I’ll just take this through and wrap it in some brown paper for you”, during which time the money for the job would have secreted back in the parcel.

To some extent she wasn’t even doing it for the money. She died just before Christmas in 1969, leaving a broken-hearted grandson of 17 years who had never known her in anything that remotely resembled good health, but who loved her to bits as the only person who never ever judged him (though this was not to say that we could not disagree about matters, but that is another, much longer story). After she died our doctor told my mother that he was pretty sure that one of the things that kept this determined woman going was her sewing – she had responsibilities to others.

But, having said she wasn’t doing it for the money, in one sense she certainly did. My grandpa was a baker with the Coop. Not a bad job as it meant he was never unemployed, even during the 20s and 30s, but hardly making a fortune. But, with his wages, and what she earned doing sewing jobs, allied to a determination and an iron discipline to save for this, they put my mother and her sister (there was only the two of them) through as teachers at a time when not only were there no grants, full fees had to paid. Why so determined? Well, by the time she was three her father was dead (Bright’s disease – basically kidney failure), and by the time she was eleven her mother had died of TB, having been ill for three years. Their care fell to their maternal grandmother who was a widow, so money – when there was money – was tight. I remember her telling me her gran kept a cockatoo, and sometimes she and her two sisters were so hungry they ate the nuts the bird was fed on – to a chorus of “eating Cocky’s nuts gran, they’re eating Cocky’s nuts”. By the time she was fourteen her elder sister was dead from TB like the mother, and three years after that her younger sister died of a particularly unpleasant form of diphtheria. That fate was not going to befall her girls, so the work was done to make sure they could qualify into a profession. When I went to University in 1970 Germaine Greer was getting going, women were burning their bras and there was much talk of “strong women” – knowing my gran (and to some extent my mother) my response was “aren’t they all?”

Like Billy, I know these days wont be back, but they had aspects that were to be much admired – the sense of community and mutual support, determination but most of all getting through a life that could be more challenging than many of us can imagine, and with no chance of support from the state.

Your piece took me straight back to that front bedroom, with material and partly finished job draped over the bed,, small bits of material and thread covering the floor, and the Singer over beside the window. Thank you.

Thank you for this reply. I love the story about the cockatoo. Your grandmother sounds like a remarkable woman. My grandfather worked as a carpet weaver in Stoddard’s in Elderslie, or the ‘carpet field’ as he used to call it. My mother worked there too for a time. Famously, it was the setting for John Byrne’s ‘The Slab Boys’ and she remembers him sweeping along the halls when he worked there, a distinctive figure even then, in his long dark coat. Now the carpet field is replaced by houses. Life was definitely harder back then, but the tendency for social isolation these days is quite sad, and so many are lacking that mutual support. Maybe staying in the same job for years was something of an institution, but it did create lifelong friendships and the stability that being part of a community brings.

That brought tears to my eyes. Such a beautiful tribute to those marvellous women and men too who gave so much to make their children’s lives better. These stories must always be remembered and recalled even though they are no longer the daily reality for their descendents. Thanks so much.

My wife protects her ever-diminishing supply of ‘Coates of Paisley’ wooden thread reels. Modern imported cotton threads are rubbish when compared to Coate’s thread. And we have inherited the old Singer sewing machine, a few years ago it was the ‘new’ imported sewing machine that ended up in the skip and the old Singer brought out of the cupboard where it had been stored – just in case!

I think the wooden bobbins used to be hung up outside the door to show whose turn it was to wash the close.

Clydebank Town Hal has a museum section which includes a display of every model of sewing machine made at the factory during its near hundred years in the town. It is well worth a visit.

Perhaps the new trend for upcycling will bring back the Singer into people’s homes!

I read this article completely concerning the comparison of most recent and earlier technologies, it’s amazing article.|

‘Blushing is for Sinners’ is a superb novel, written wonderfully. It should be a movie. Some film maker out their would be wise to buy the rights, Peter Mullan maybe?

This is so true, Jim – the juxtaposition of the two contrasting time lines, the scenes of high drama and suspense, the strong characterisation and the dialogue would all lend themselves to a film or TV drama.

I love the history of your grandmother and I was born an raised in Kilbarchan. Came to the USA in 1961. Would love to have your book- is it available in the USA?

Thanks Sally. I lived in Ramsay Crescent, near Tandlehill Road in Kilbarchan from 1975 to 1981 and went to the old Kilbarchan primary school which is sadly no longer there. I don’t think the village has changed much over the years. I don’t have a US distributor, but my book is available on Amazon in paperback and Kindle. You can contact me through my website and all the links are on there: tracypatrick.org