The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation

Scott Hames is Lecturer in Scottish Literature at the University of Stirling. He has edited two books of essays on modern Scottish literature and national identity and is an occasional contributor to Bella Caledonia. In The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation he examines the influence of writers and intellectuals in shaping the campaign for constitutional change in Scotland from the 1970s to the establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999, exploring the relationship between the ‘dream’ of national empowerment and the ‘grind’ of electoral strategy, and examining critically how the work of authors such as William McIlvanney, A.L. Kennedy, Irvine Welsh and James Kelman relates to the concern with articulating a distinctive and authentic Scottish voice during the period of the Thatcher and Major governments.

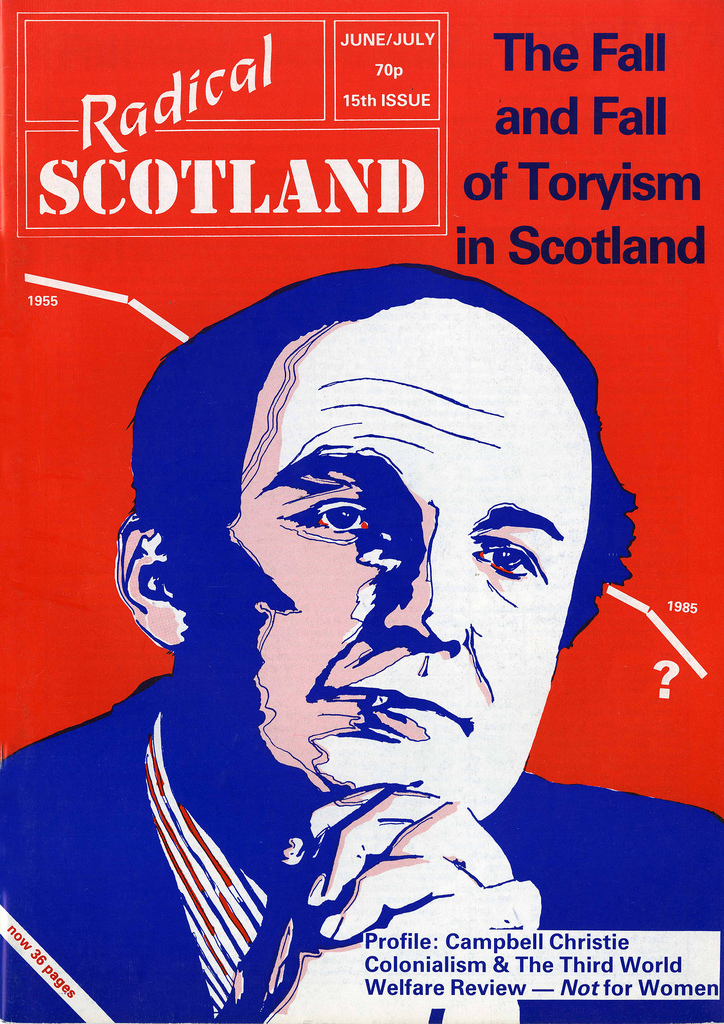

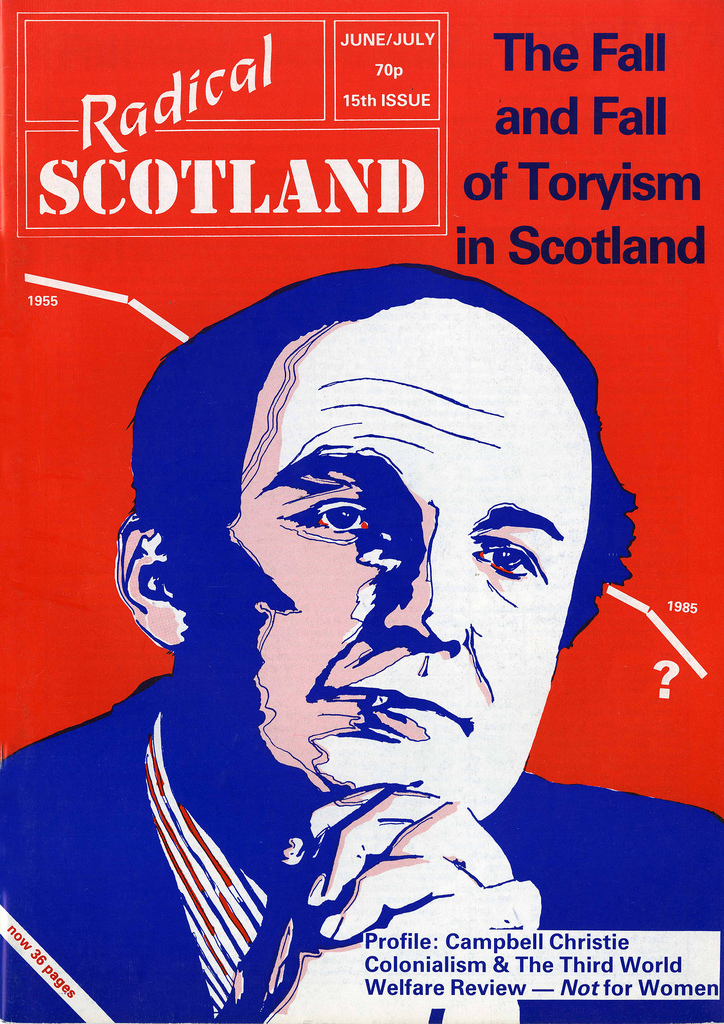

Hames highlights the influence of writers and thinkers such as Tom Nairn, Stephen Maxwell, Jack Brand, Neal Ascherson and Christopher Harvie in shaping the initial response to the unsatisfactory outcome of the devolution referendum of 1979, but a distinctive feature of the book is a strong focus on the small magazines which engaged with Scottish political and cultural debates in the pre-internet period, particularly Radical Scotland, Calgacus, Cencrastus and the Edinburgh Review.

While Hames is sympathetic to the cause of Scottish self-government, he is at pains to maintain a critical distance from his subject. He is right to subject the sometimes exaggerated claims of cultural vanguardism to critical scrutiny, but his scepticism often becomes mannered, not to say loaded and laboured. Scotland’s claims are ‘uncertain’. Assertions of popular sovereignty are dismissed as ‘nationalist notions’. Scottish nationalism contrives to be perversely ‘a-cultural’ while retaining a ‘tweedy aura’. When it is not being expressed through the ballot box, Scottish national consciousness is only ‘latent’. Home rule activists are characterised as ‘obsessives’ fretting over ‘nebulous difference’ and nursing ‘national injury’. Scots is only a ‘semi-separate tongue’. The Scotland of the 1990s is reduced to being ‘marginal’ and a ‘semi-nation’. Scots appear to have only a ‘half-belief in national belonging’, and Scottish identity is a ‘provisional choice’. In this narrative, Scotland exhibits a peculiar form of exceptionalism, a unique ambivalence about its authenticity. One is left wondering how this etiolated, twilight entity, with only a tenuous grip on national consciousness, could have come to possess the distinct ‘intelligentsia’ and ‘densely-networked’ civic realm which Hames identifies as key drivers of the campaign for devolved government.

Also, the application of academic rigour is decidedly uneven when it comes to the evaluation of evidence, the assessments of some observers and commentators winning an uncritical acceptance not accorded to others. For example, Benedict Anderson’s wholly misconceived and ahistoric assertion that ‘already in the seventeenth century large parts of what would one day be imagined as Scotland were English speaking’ is recorded without a quibble. And Hames is content to accept the distinction George Kerevan makes between a ‘rising intelligentsia’ of post-war graduates and organisations such as the Campaign for a Scottish Assembly (CSA) ‘cast too much in the mould of the apolitical Covenant movement of the Fifties: too middle class, too Protestant, too male, too middle-aged’ without any qualification.

The cultural revival led by writers and artists such as Edwin Morgan, Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochhead and Ian Hamilton Finlay after the devolution referendum of 1979 was able to combine respect for Scotland’s indigenous cultural resources with an openness to ideas from elsewhere. Oddly, Hames doesn’t attempt to engage with any of this, preferring to wear his studied scepticism about the existence and viability of a distinct Scottish cultural identity as a badge of detached academic rigour.

Hames’ relentlessly sceptical stance tends to undermine his own account of the influence of writers and intellectuals in establishing consensus around a post-referendum narrative in the early 1980s. He writes of the assembly offered in the 1970s dismissively as only ‘half-wanted’ and ‘nobody’s dream’. But if the feeling that the failure to grasp it was a lost opportunity had not been widely shared, that narrative would have had little traction.

Hames is curiously uncurious about the social, political and cultural networks which took the cause of Scottish self-government forward in the 1980s and 1990s, the people involved and the connections between them. His analysis of the forces at play during the period remains at the level of airy academic abstractions such as ‘the intelligentsia’, ‘Civic Scotland’ and the ‘elite’. He argues that ‘the Scottish elite took over a half-constructed, semi-derelict project’ of devolution after 1979, though this elite is not defined or examined in any depth. While the Constitutional Convention established in 1989 can be seen as an elite project, the Campaign for a Scottish Assembly (CSA) which preceded it, and was up and running the year after the referendum, was by no means an elite organisation. It grew out of the links which had been established between activists of various parties and none during the referendum campaign. It was grass-roots and multi-faceted. It included members of the SNP, the Labour Party and Jim Sillars’ Scottish Labour Party, as well as Liberals, Communists and Greens. The Scottish Ecology Party, forerunner to today’s Scottish Green Party, had been established just in time to campaign on the ‘Yes’ side in 1979. Hugh Miller of the Scottish Republican Socialist Party was a key figure in the Edinburgh Branch and nationally. Activists with widely different political perspectives admired his enthusiasm and commitment and respected his organisational skills. Pace George Kerevan, in its diversity and activist-driven creativity, the CSA was more closely akin to the local ‘Yes’ groups of the 2014 referendum campaign than John McCormick’s douce Covenant Movement.

Hames suggests that there was little examination of the content of Scottish culture by writers and intellectuals in the period after the 1979 referendum. In fact, there was rather a lot. Scottish Journey (1935), Edwin Muir’s bleak assessment of Scottish culture and identity was widely referenced during the period. A new edition had been published by Mainstream in 1979, with an introductory essay by T.C. Smout. Barbara and Murray Grigor’s Scotch Myths exhibition (1981) stimulated a series of articles examining aspects of the representation of Scottish identity and culture in The Bulletin of Scottish Politics and Cencrastus, but Hames’ strict focus on literature allows him to confine his acknowledgement of this fact to a footnote, on the ground of lack of space. The cover of the first issue of the relaunched Radical Scotland published in the spring of 1983 illustrates the quote attributed to Tom Nairn, that ‘Scotland will be free when the last minister is strangled by the last copy of the Sunday Post.’ Here, the new Editorial team were not asserting a tentative or questionable Scottish cultural identity but contesting the nature of Scottish identity and signalling a break with the past. It is noteworthy that the Kirk and Presbyterianism barely surface in Hames survey of the writing of the period, though in his criticism of the work of James Robertson the Disruption of 1843, a singularly Scottish event, does get a mention.

Hames quotes the following passage from Robertson’s novel, And the Land Lay Still (2010):

“There were magazines recording and encouraging this process of self-exploration. They were small-scale, low-budget, sporadic affairs, and their sales were tiny – a few hundred, a very few thousand – but the people running them weren’t doing it for the sales. They were doing it to address the pervasive sense of wrongness. And the people who read them – culturally aware, politically active people – were hungry for what they provided. More than anything, perhaps, the magazines said you are not alone.”

Sadly, we learn less than might have been expected about these people. Kevin Dunion and Alan Lawson, the successive editors of Radical Scotland are identified, as are Joy Henry, the editor of Chapman, and Peter Kravitz, the editor of Edinburgh Review. Norman Easton, editor of the predecessor to Radical Scotland, Crann Tára, is not identified, neither is Ian Dunn, the co-founder of the Scottish Minorities Group who edited two issues of Radical Scotland prior to the relaunch of the magazine in 1983. With the exception of Cairns Craig, the members of the editorial team at Cencrastus remain anonymous.

Several members of the new editorial team at Radical Scotland had been active in the SNP 79 Group, and involved in the production of its newsletter, 79 Group News. Following the proscription of the 79 Group from the SNP in the autumn of 1982, they were in need of an alternative vehicle for the promotion of their ideas. However, Hames is mistaken in his claim that the magazine was taken forward by ‘an entirely new editorial team’. There was an element of continuity, and that played a part in facilitating the change to the new regime, but it is worth noting that an interesting strand of writing on sexual identities and minorities in Scotland did not survive the transition. Hames references an excellent essay by Douglas Robertson and James Smyth on the story of Radical Scotland, about which Robertson has first-hand knowledge as a member of the editorial team. I remain astonished that it was rejected by the journal Scottish Affairs and is still unpublished.

While my personal knowledge of the period has led me to be acerbically critical of several aspects of this book, I do believe that it is a valuable piece of work, breaking important new ground in exploring the ‘complex and pervasive intermingling of Scottish literature and politics over the past few decades’ and highlighting the part which small political and cultural magazines played in bringing that about.

Hames is right to warn against a reductive critique of Scottish writing and writers. He provides valuable insights, such as the suggestion that ‘Loosening the grip of MacDiarmid’s acolytes on ‘Scotland’ as a topic and possibility was arguably the crucial legacy of Scottish International.’ He draws our attention to observations by Scottish writers which remain all too relevant. Tom Nairn’s comment that English nationality has little political horizon beyond Anglo-Britain and its imperial residues remains true today as we teeter on the edge of Brexit. James Kelman’s parody of the stand-off between Civic Scotland and the Major Government over devolution, in which ‘the height of their defiance is to carry on waiting until they give us power,’ has an uncomfortable resonance in the political predicament in which Scotland now finds itself. Hames is correct to conclude that Scottish devolution is not only a set of political structures but a cultural condition, but surely mistaken in suggesting that it is “a condition just short of independence” – as we are currently finding out.

There is much more to explore and much more that can and should be written about the relationship and interactions between culture and politics in the period between the referendums of 1979 and 1997. Scott Hames has made a welcome start.

Scotland! https://soundcloud.com/epsilon60/scotland

I read most of this article word for word, until I developed a conclusion that Mr. Hames authored his own work from the standpoint of so much unexamined baggage of his own, that whatever he has produced must be seriously distorted. You have been more than fair in urging his work be regarded as “an important contribution”; you will perhaps, therefore, be also able to accept that your own willed generosity might not be shared by others.

Scotland is often portrayed as independent (or quasi-independent) in near-future science fiction. By 1997, for example there has appeared the Caledonian Habitation Zone in the Judge Dredd universe, and Ken MacLeod had published his first novel (I have only read his later work). Partly, I suppose, because writers don’t want to be caught out by independence and have their futurism horribly dated (this poses a particular problem for institutions like the BBC). Any survey of Scottish literature that excludes science fiction (yes, I am aware that Alasdair Gray wrote some) has a hole in its head and one eye put out.

I cannot tell if Hames recognizes this (and his chapter dates only go up to 1992, apparently), but perhaps I am looking for the wrong book: the interplay of science fiction and independence movements.

Graeme chides me (as quoted by Scott Hames) for characterising the 1980’s Campaign for a Scottish Assembly as ‘cast too much in the mould of the apolitical Covenant movement of the Fifties: too middle class, too Protestant, too male, too middle-aged’. In fairness, the quote comes from an article I wrote in 1983! With the benefit of hindsight, I will grant this characterisation was and is a mite too polemical. On the other hand – in the aftermath of the abortive 1979 referendum, subsequent general election, collapse of the SNP vote and Thatcher’s victory – a new debate had opened up that went beyond simply reiterating the demand for a Scottish Assembly. New forces in the labour movement had come over to independence, seeking a more radical approach. It was in this context I criticised the CSA LEADERSHIP for being too cautious – I think correctly. I remember speaking at CSA events where this debate came out into the open. That said, Graeme is correct to say the CSA reflected new social forces coming into play. History is not something apart. It is made by women and men choosing to act. In that sense, Scotland in the 1980s recast its political self. Change came from within, not without. We are seeing the results today.