Make Rojava Green Again: Building an Ecological Society

As part of our series to celebrate International Women’s Day 2020, exploring women’s non-fiction we review Make Rojava Green Again: Building an ecological society, Internationalist Commune of Rojava, (London 2018, Dog Section Press, £6 )

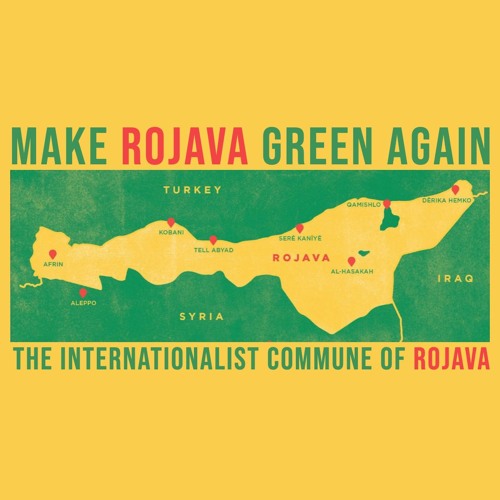

Ecology is a central pillar of Abdullah Ocalan’s political philosophy – the philosophy that underlies the Rojava revolution – but it is no secret that physical achievements in this field have been limited. Looking at Rojava, the predominantly Kurdish, autonomous region of northern Syria, we might be impressed by the creation of grassroots democratic structures and by the building of bridges between different ethnicities, and we might be amazed by the drive for women’s rights, but ecological changes are less evident. The Internationalist Commune, who have produced this small book, is made up of young people who have come to Rojava from all over the world to help build a new society, and they have taken up the challenge of assisting the local organisations in addressing the ecological deficit. The book is part manifesto, part practical guide – and a call for solidarity, practical and financial.

When I visited Rojava in May 2018, we paid a fleeting visit to the Internationalist Commune, and the dedication and enthusiasm of the young volunteers was palpable. I remember reciting to myself (with a tinge of jealousy) Wordsworth’s observation on the French Revolution: ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very Heaven!’ Of course, we were aware even then of how precarious the region’s new freedoms were. Afrin had been occupied by Turkey earlier that year, and the Turkish border was a constant looming presence. Today the situation is even more uncertain, but the Internationalist Commune, like other parts of Rojava, continues the everyday work of building a society that can provide a living alternative to ‘capitalist modernity’.

The book’s short bibliography includes Ocalan, Bookchin and Engels, alongside ‘Guidelines on the safe use of urine and faeces in Ecological Sanitation Systems’. This is a fair indication of its content, which moves from sweeping political theory to technical, as well as political, solutions.

The first half of the book looks at the theory of social ecology that was developed by Murray Bookchin and taken up by Abdullah Ocalan, and at the ecological and social crisis created by ‘capitalist modernity’. It describes how humanity became alienated from nature, and puts forward the need to rebuild the connection, so that human awareness and reason works with nature rather than against it. While the historical background is important in showing that there is nothing inevitable in the current situation, the sort of sweeping historical narrative given here loses power through being unrealistically neat and uncomplicated. Much of the early history is conjectural, as it is in the texts on which this account is based, and the later history makes no acknowledgement of the counter currents that have continually questioned the onward march of mechanistic rationality. (Wordsworth would have something to say on that too.)

“What is it about the social structures of Rojava that so inspires the fierce loyalty of its defenders and its people?

This book answers that question. In language that bridges the Utopian and the concrete, the poetic and the everyday, the Internationalist Commune of Rojava has produced both a vision and a manual for what a free, ecological society can look like. In these pages you will find a philosophical introduction to the idea of social ecology, a theory that argues that only when we end the hierarchical relations between human beings (men over women, young over old, one ethnicity or religion over another) will we be able to heal our relationship with the natural world.”

-Debbie Bookchin – 2018

This might seem a relatively minor irritation, but for those who do not already support the ideas being put forward, it makes it easier to dismiss them. Similarly, while the book clearly states the need for radical grassroots democracy, it doesn’t properly make the argument as to why a more centralised system would fail. Perhaps, for those living in Rojava, in a system where direct democracy is beginning to allow communities to be actively involved in shaping society according to shared and not individual interests, the value of this seems obvious, but for many readers the case has still to be made. When even a progressive organisation such as Scotland’s Common Weal looks to centralised efficiencies rather than democratic local engagement, as in their proposed Green New Deal, then these arguments need to be spelt out. In Rojava, politics is an integral part of people’s daily lives, and this is the best guarantee that actions remain rooted and relevant and under constant scrutiny.

In the second part, we go from the general to the particular, with an honest and informative round-up of the problems and possibilities affecting Rojava’s ecology. It begins with the legacy of the Assad regime, which turned much of the area into Syria’s breadbasket under an unsustainable wheat monoculture, and with the continuing threats from Turkey – including extraction of water and crop burning, as well as military attack and economic embargo.

It looks at the limited, but still important, achievements that have been made since the establishment of autonomous control – diversifying crops and reducing the need for irrigation, planting trees, setting up a nature reserve, and establishing agricultural co-ops. And it also looks at some of the other things that could be done, such as waste recycling and composting, and local green energy generation. Perhaps more links could be made to show how Rojava’s democratic system could encourage and nurture these changes, but this is a unique and useful account.

The final chapter explains the Internationalist Commune’s role, which has three parts. The first concerns education. They teach language, political theory and practical ecology to visiting internationals, and develop ecological understanding in wider Rojava society. The second is a practical contribution to building the new society, through the creation of a co-operative tree nursery and through research into green technology. And the third is the building of international solidarity in the joint task of making Rojava Green Again and avoiding ecological catastrophe. The writers state, ‘we hope that we can contribute to finding ways out of the ecological crisis of our time’. The work that they are doing to foreground ecology in the Rojava revolution, and to link social revolution into green politics provides an important step along the way.

As befits a radical text, this book can be read freely on the internet, but it is still nice to buy a physical copy, not just because proceeds go to the Rojava project, but because it is a beautiful thing in itself. The care that has gone into the design is symptomatic of the joy and commitment of those dedicated to creating a better world.

See also: https://makerojavagreenagain.org/