Interview with Murdo Macdonald, author of Patrick Geddes’s Intellectual Origins

Can you tell us a bit about the process of writing and completing the book. How long have you been working on it? How did you decide to organise it?

I’ve been exploring Geddes in a serious way since 1992 when I edited a Geddes edition of Edinburgh Review. The idea of writing a book grew over the years but the real issue was finding the right focus. Geddes is a wonderfully complex thinker who achieved a great deal in areas as diverse as botany, geography, ecology, sociology, urban planning and cultural activism. Very often he had a pioneering role in helping to establish academic disciplines which we take for granted today. A great deal had been written about him but I was very conscious that much of his thinking has still not been fully addressed. From my own perspective I could see a particular gap, namely the Scottish dimension to Geddes’s thinking – so that became my starting point.

You situate the book in the Scottish generalist tradition, can you tell us how Geddes evolved out of this tradition? There are various theories that this came from his linguistic background and his childhood education. What’s your view?

Well, it’s perfectly true that like many Scots he had a rich linguistic background to draw on including Scots and Gaelic as well as English, but with respect to his interdisciplinarity I think what was really important is that he grew up at a time when interdisciplinary approaches were commonplace in Scotland. I only became aware of this because I was fortunate enough to be taught by George Davie at the University of Edinburgh. George was author of the classic account of Scottish universities in the nineteenth century The Democratic Intellect and as a postgraduate I help to publish its sequel The Crisis of the Democratic Intellect. As a result of that experience I realised that Geddes’s interdisciplinarity was part of a Scottish intellectual tradition, and that aspect of Geddes had been missed in previous accounts. So that Scottish interdisciplinary tradition gave me a framework within which to think about Geddes. It also helped me to structure my book, for my concluding chapter focuses on Geddes’s farewell lecture to University College Dundee given in 1919 before he took up a new role at the University of Bombay. It is one of the great statements of his interdisciplinary approach.

Geddes’s interdisciplinary view, his generalism (to use George Davie’s terminology), continues the thinking of an earlier generation of Scottish thinkers. That tradition includes the pioneer of educational theory and teacher training Simon Somerville Laurie and the Milton scholar David Masson, both of whom Geddes knew. It became natural for me to consider Geddes alongside them and as part of the same tradition, rather than seeing Geddes’s interdisciplinarity as primarily influenced by nineteenth century French thinkers. Those French thinkers, not least Comte and Reclus, were of course very important to him but the point is that his receptiveness to their thinking was because he was already part of an interdisciplinary tradition. So for Geddes it was a genuine Auld Alliance of thinkers, rather than simply French influence. The wider historical and international dimension to Scottish interdisciplinarity is also important here. Laurie in particular drew heavily on the thinking of the seventeenth century Czech philosopher Jan Amos Comenius and Geddes followed suit in his admiration for Comenius’s interdisciplinarity.

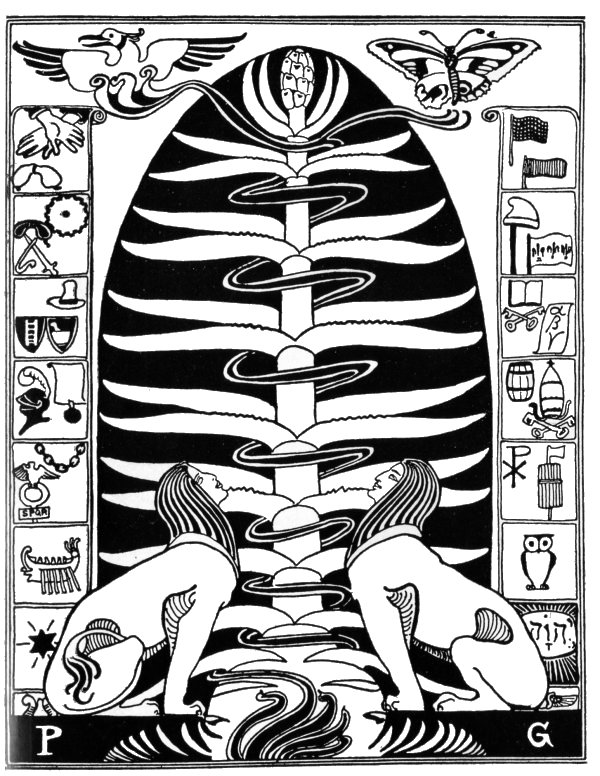

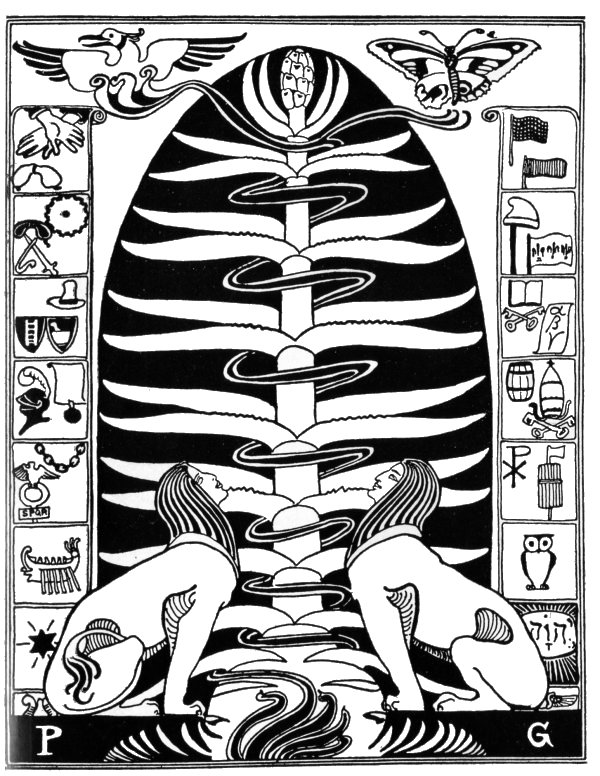

Geddes is one of the great visual thinkers. His friend Rabindranath Tagore said of him that he had ‘the power of an artist to make his ideas visible’. I would like to think that someone would soon produce a well-illustrated book on Geddes and the visual. There is a real opportunity to do so at the moment because a great deal of Geddes’s visual material held by the Universities of Edinburgh and Strathclyde is in the process of being digitised.

The importance of visual methods to Geddes is directly related to his interdisciplinarity, for the visual encourages a holistic approach. That is something that George Davie discusses in The Democratic Intellect. Geddes called his Outlook Tower, packed full of images and models as it was, an Encyclopaedia Graphica. In doing so he was also drawing attention to the fact that the tower was in Edinburgh, the city in which those great statements of interdisciplinary thinking, the Encylopaedia Britannica (to which Geddes was a contributor) and Chambers Encylopaedia were founded.

In chapter three you explore the idea of ‘garden and world’. Can you explain the importance of the garden in Geddes’s work throughout his career?

Geddes grew up in a small cottage with a beautiful large garden on a hillside looking over the river Tay towards the city of Perth and onwards to the Highlands. That relationship between garden and wider human-ecological region inspired him throughout his life. Indeed he saw urban planning as first and foremost a growth of gardens and parks, whether in the opportunistic use of gap sites in Edinburgh, or as parts of wider planned environments, as in his unexecuted plans for Dunfermline and Dundee. And those gardens and parklands link directly via rivers, mountains and oceans (what Geddes called ‘the valley section’) to the wholeness of the planet itself. In his farewell lecture at Dundee he puts it thus: ‘this is a green world’ followed soon afterwards by his wonderfully concise ecological statement: ‘by leaves we live’. Never was the significance of ecology of the planet for the survival of us all more clearly stated. And never has it been more relevant than today.

You explore ‘Education, Anarchism and Celtic Revival in Edinburgh’ in the book and the influences of Kropotkin and the Reclus brothers are clear. How do you find the tension between ‘radical Geddes’ and ‘establishment Geddes’ through his life?

It’s certainly an interesting question for debate in our own time, but for Geddes I don’t think it was a tension. He was profoundly pragmatic, and he believed in social evolution. That means he didn’t expect things to be ideal or perfectible in his own time. So he would accept establishment patronage if it furthered his aim of moving towards a just, ecologically sustainable society (which itself would always be evolving). I don’t think he was naïve in that, for he saw society as an evolutionary process, and the establishment he had to deal with and gain resources from was just one expression of the current state of that evolution. But the crucial thing he recognised is that human decisions could guide social evolution, and that such guidance could be for good or for ill. He would be disappointed that since he made these points about social evolution so many political choices have favoured the destruction of the planet for short term financial gain (‘we live not by the jingling of our pockets but by the fullness of our harvests’). On the other hand he would be heartened at the growing success of renewable energy, and see that as indicating hope for the future of what he called a ‘neotechnic’ society.

You write about ‘Saint Columba as point of reference’, Coomaraswamy, Baha’ism and Theosophy. The element of the spiritual (if not the religious) is a thread throughout Geddes’s work. How are you understanding this in his wider work?

Geddes was well versed in the Bible and books such as John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress but he saw religious texts as sources of wisdom and debate not of dogma. For example he saw no conflict between science and religion, seeing them as complementary ways of approaching the world rather than as in any sense antagonistic. His deep spiritual commitment emerges again and again not least through his friendships, which numbered several of the key spiritual thinkers of his era. In Scotland they included Alexander Carmichael (of Carmina Gadelica fame), John Kelman (who amongst much else wrote The Faith of Robert Louis Stevenson), Alexander Whyte (analyst of Dante and correspondent of Cardinal Newman) and Whyte’s wife Jane Barbour (whose advocacy of Baha’ism brought Abdul Baha to the Outlook Tower).

Geddes’s wider friendships included many Indian spiritual thinkers not least, along with Coomaraswamy, Rabindranath Tagore. Geddes’s former student, Annie Besant, headed up the Theosophist movement in India, and Geddes’s close collaborator the artist John Duncan became a Theosophist in 1909. So Geddes was close to and interested in all approaches to spiritual issues, the more broad-minded the better. Perhaps his view is summed up by the fact that he regarded the Outlook Tower as an ‘Inlook’ Tower also, a place a meditation.

In a later chapter you explore the relationship between Celtic revival and Bengali revival. Can you tell us a bit how these two cultural movements interacted?

A crucial moment was the Paris International Exhibition of 1900 which occurred soon after Geddes’s major period of Celtic revival advocacy in Edinburgh. It brought together Geddes and John Duncan with key figures who would develop the Bengal revival, such as Geddes’s friend the remarkable Irish educator Margaret Noble, who took on the name of Sister Nivedita as a disciple of the Hindu revivalist, Swami Vivekananda. As noted above, Geddes would later have close links with both Ananda Coomaraswamy and Rabindranath Tagore.

Geddes and Tagore have a great deal in common for they were both strong advocates of the arts and at the same time saw environmental regeneration as crucial to cultural revival. One of the major Indian figures Geddes met in Paris in 1900 was the pioneering scientist Jagadis Chandra Bose whose biography he would later write. One of the regrets I have about my own book is that I wasn’t able to discuss Geddes’s links with Bose in any detail, but that just draws attention to how much remains to be done.

When you reflect on the whole of Geddes’s life and career, do you have a reflection on what was the most important work he did? For what should he be remembered?

That would be an easier question to answer if Geddes had achieved less … so I think the answer must be his totality, his absolutely committed interdisciplinarity. If he had done nothing else other than commission Ramsay Garden in Edinburgh he would be remembered for it. But that was just part of a network including the Outlook Tower and much else. And he was a pioneer of ecology, sociology, planning and geography. And in addition he led the Celtic revival in Scotland and supported cognate revivals elsewhere.

Any one of those could be seen as a legacy achievement, worthy of remembering Geddes by. The crucial thing is that every single one of those achievements was part of a wider educational aim. So Geddes should be remembered as someone whose aim was to educate us fully about the planet and our responsibilities to it and to ourselves. That is why remembering him is important.

Many thanks for putting this on my radar, and great appreciation to Murdo for authoring this work. Patrick Geddes has long been an inspiration for myself, and this continues – now around 100 years on. I often wonder, ‘what would Geddes make… of this or that? … in our day. Today it is some wondering about what he’d make of the current pandemic, in particular, any evolutionary message in this for us, as a now a global collectivity. He would have lived through the Spanish Flu. What was his view? Would he now be making the connection between our learning from Covid-19, for the needed collective action on climate change? Look forward to mining Murdo’s book on Geddes for more nuggets of insight.

This is a wonderful commentary on Geddes and the Scots generalist tradition. I am particularly grateful that you draw out the spiritual aspect of it, and when I read the book I will be keen to learn more of those internationalist connections.

There is a tradition of what Davie spoke of as “metaphysical Scotland” finding expression here, a tradition that goes deeper than the stuck forms of religion we have often been lumbered with, but which I know in its primal essence flows on in the carrying stream today. It helps to make Scotland distinctive in the eyes of many visitors.

It reminds me of JM Barrie’s stage instructions in “Mary Rose” for the Isle of Harris ghillie, Cameron (who was very likely inspired by JMB’s 1912 visit to the island by the personage of the uncle of David Cameron, the Harris garage owner, also of Community Land Scotland). Barrie specified that his Cameron was to be portrayed, ”in the poor but honourable garb of the gillie [and] not specially impressive until you question him about the universe.”

Your work, Murdo, has long helped to maintain the legitimacy of that generalist yet metaphysical tradition; and I, for one, thank you profoundly for having helped me (back in the 1990s) to wake up, albeit as a very slow pupil, to this aspect of our intellectual heritage.

What an inspiration Murdo and can’t wait to discover more of Geddes and how it resonates in my own life view with so much more to learn even at this elderly state. Have only in the last decade or so discovered some of this amazing knowledge that I was never privy to in my working class scheme upbringing in Glasgow. But fortunate to have had the influence of those kind of people that impart that Scottishness a love of learning. They must have guided me to these more recent discoveries and have to thank James Kelman for that.

Is it (much) more difficult to be a generalist these days, given that there has been something of an explosion in disciplines? Perhaps there are simply many different configurations of synthesists, but no pan-disciplinary generalists? There is almost a fractal quality in the degree of some specialities these days, I gather. Ever branching.