Illustrated Declaration of Arbroath

Andrew Barr launches his Illustrated Declaration of Arbroath this month. We discuss the project:

Can you tell us a bit about how the project came about? What was your motivation?

As soon as I realised the 700th anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath was coming up in 2020 I knew I wanted to do something creative to mark the occasion. I noticed that all the existing books on the Declaration were academic, and I wanted to do something quite different to really bring the whole thing to life. So I began drawing, taking inspiration from the wording of the document. But I also started writing, exploring the Declaration’s meaning and significance from a cultural perspective. A book became the natural way to pull the whole thing together. I started working in 2018, and I was delighted when the Saltire Society agreed to publish it.

What is the significance of the Declaration of Arbroath?

The Declaration is one of the primary foundation stones of Scottish identity. It sets Scotland out as a sovereign nation, but it also sets out an early idea that nationhood is about much more than the person who happens to rule it. It’s about a ‘community of the realm’, it’s about all of us, and leaders have to be accountable to the people they serve. That kind of thinking was quite ahead of its time in 1320.

Do you think we are getting any better at learning and teaching our history?

Scotland is in a much better place now than it was a few generations ago. We’re becoming better at celebrating our history and culture, but there’s still a long road ahead, and progress can sometimes seem slow. I think Scottish culture is underserved in areas like broadcasting, for instance. We don’t see much our history reflected back at us in the way other countries usually would. Those with a knowledge of Scottish history are often self-taught – we’ve gone to find things out for ourselves.

What do you say to the people who think that this is ancient history, that its not relevant to 21C Scots?

History doesn’t take place in isolation. You can find threads of ideas which last for hundreds of years, and which manifest themselves in different ways when picked up by different people. One of the things I really enjoyed about writing this book was looking back at how the Declaration has been commemorated over the last hundred years, at the 600th anniversary in 1920 and then the 650th anniversary in 1970. These commemorations are always set against a backdrop of what else is happening in Scotland at the time, both culturally and politically.

The Declaration still has a way of inspiring people, but people also debate what it really means and what should be taken away from it. And that to me just goes to show how powerful this document still is, even after 700 years.

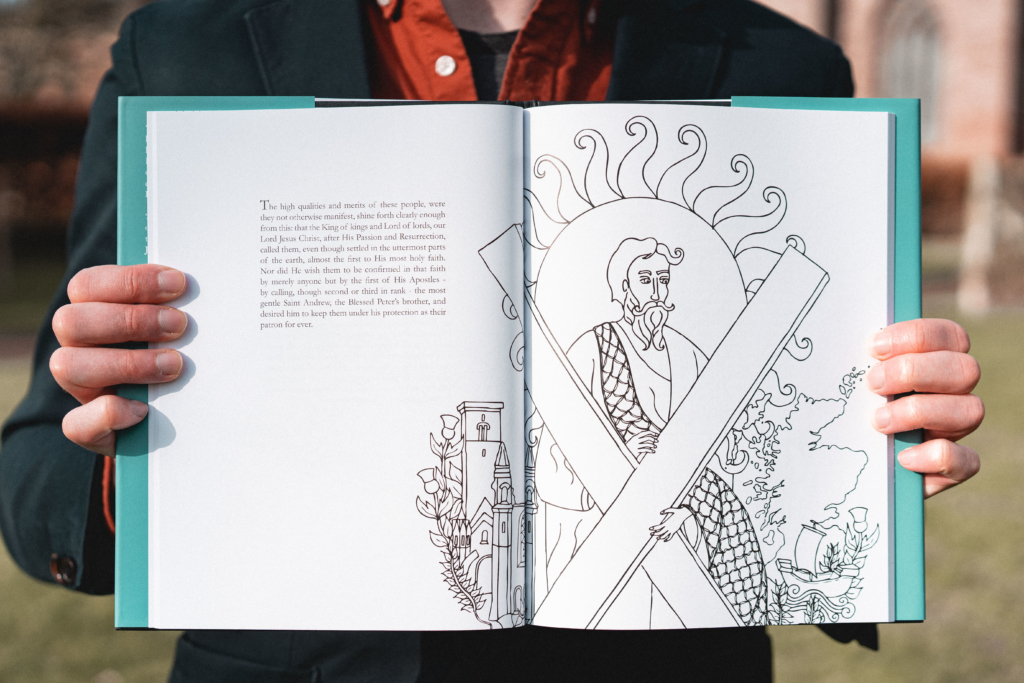

Can you say something about the style of illustrations you used and the creative process?

Traditionally we associate the Declaration of Arbroath with just one image, which is that rectangular piece of parchment with wax seals dangling beneath. But of course I couldn’t fill an illustrated book with just one image. So I began to look very closely at the wording of the Declaration, and realised the text itself was full of images: saints, kings, battles. It’s got everything. I wanted to translate some of that into my illustrations and bring the whole Declaration to life. The illustrations are fairly simple black and white line drawings. I liked the idea that the wording of the text is quite stark and bold, and the illustrations were meant to match that.

I’m sorry the virus has disrupted launch. What plans were there to celebrate the anniversary and what is going on to replace live events?

We had sold out the Webster Theatre in Arbroath for a brilliant cultural evening of music and entertainment. It was due to be one of the big events of the anniversary weekend, but sadly we’ve had to postpone it to a later date. In the meantime Lesley Riddoch has put together a brilliant documentary film on the Declaration, which is now available to watch for free online. I was delighted to be a part of it. It was a quick turn-around and a real community effort.

I’m hopeful we can still celebrate the 701st anniversary of the Declaration next year, and give this part of our history the recognition it deserves.

The Illustrated Declaration of Arbroath is now available to order online at AndrewRBarr.com

I wish I could have calligraphed this; an example of the style I created is at the bottom (final photo) of this article at my blog: https://bunkunin.com/2019/11/02/watching-the-fall-and-the-fall-of-the-world/

I mention this because I’d wondered just how visual art comes to be at Bella.

I do hope the illustrated version doesn’t depict that part of the text which describes the mythical Scottish invaders as “having first thrown out the Britons and completely destroying the Picts”.

My understanding of actual Scottish history is that the Britons and Picts who occupied Scotland before the Scots (and Angles) arrived were neither thrown out or destroyed. The Picts (who were linguistic kin with the Britons but untouched by Rome) were culturally assimilated by the Gaelic Scots of the west. No genocide occurred. The Britons maintained an independent Welsh-speaking kingdom and principality from Dumbarton to Carlisle for many hundreds of years, despite Gaelic Scots to their north and west, and despite Angles to their east ruling a greater Northumbrian kingdom from its capital in Edinburgh. Relentless attacks from the Norse finally led the ruling elite of the Britons (by then calling themselves Cambrians) to sail down the Clyde to find a welcome in north Wales, but leaving their people behind in Strathclyde, Ayr and Lanark. David I of Scotland was called Prince of the Cambrians. William Wallace (whose surname means Welsh) was one of the same people. Welsh is a more common surname in Scotland than in Wales. Even if we just mentioned William Wallace and Irving Welsh, we would have a good grounds for believing that it has served Scotland well that the Britons were not “driven out”.

The Picts are less easy to pin down, but we can surmise that there complete destruction (had it happened) would have deprived Scotland of unnumbered essential contributors.

In conclusion, Scotland should glory in its multiple origins and threads of DNA and humanity. The Declaration of Arbroath is a jewel of its time, but beware the nonsense within its text.

Thank you for this Adrian

It needed to be said and how well you did…..

“Scotland should glory in its multiple origins and threads of DNA and humanity”

BRILLIANT!

For several decades, the “mystery” of the Picts has been clear: they spoke a P form of a Celtic language, i.e. they were Britons. Surely there seems little point in dredging up debunked theories, even if prompted by the mediaeval claims of people keen to assert their own political independence in the face of powerful enemies.

STONE LASTS FUR NEARLY EVER

Scottish Thistle Coin 1602, a photo by Tropic~7 on Flickr. There was an extremely interesting blog posting on Wings over IRVINE WELSH: IN PERSON, a photo by EIFF on Flickr. Bella Caledonia has today published an original article by Irvine