The Infinity Of Debt: FROM THE PROVINCE OF THE CAT

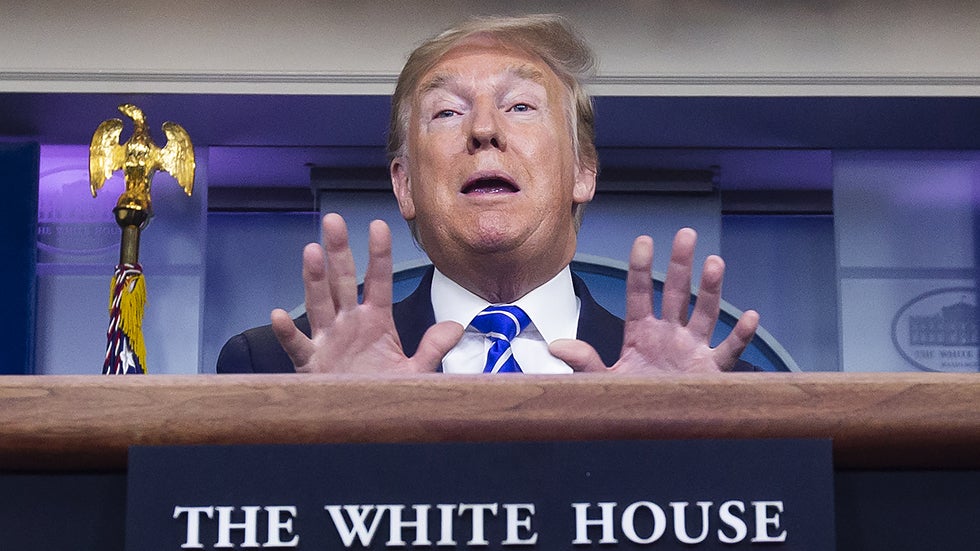

As I listened to Donald Trump, the Potus, the President of the United States, suggesting that the way to “knock the virus out in a minute” was to inject disinfectant into Americans I realised that a strange new form of infinity had slid in un-noticed from some far-flung outer nebula of the universe and had entered, somehow, into my mind and into the mind of everyone who had watched TV at that moment. As the reality slowly dawned, that there was now no “reality” and that the phosphorous and sulphurous parameters of the volcano of human imagination, on which I depend, had melted and turned to gas I realised there was no longer anything left to protect me from either my own despair or the chaos of the random disorder of political entropy. And I suddenly felt very alone, surrounded by five and a half billion others on this beautiful blue dream-ball of a planet. I went out and stared hungrily, hard and eager, into the vast April night at Venus burning like a torch in the low North-Western sky, hanging gloriously over the vast Caithness bog, signalling the way to somewhere, if only I knew where? It was then I realised I was scared.

How strange then, at that moment, that these words by William Wordsworth should enter into my mind like a herd of nervous deer,

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

Wordsworth wrote that poem, published in 1807, when he was in his early thirties, his radical years behind him and his reactionary Tory years yet to come. The French Revolution still burned its radical fire in his blood and his disgust at the on-going Industrial Revolution had yet to metamorphosise into the fear of change which haunts the frail, greedy heart of all conservatives. Wordsworth, literally, gave his radical heart away. The latter part of his life, politically, was indeed “a sordid boon!”.

Time passed. The night was breathless and beautiful. Venus still burned brightly. The pandemic still raged across the world, killing silently, from person to person, from country to country. The taxi meter of death kept running. The sky was Moonless and full of infinite stars. There I was: one man standing powerless on the Northern edge of Scotland. This pandemic has brought us all to the edge.

If I was wise, or a Stoic philosopher – like Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180 AD) – I would understand that the pandemic isn’t really under my control but the way I behave in response to it is. Marcus Aurelias would go on to argue that the way I behave in relation to any challenge is my responsibility, but I would say as well as being a Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus (like death he had many names) was also a Roman Emperor. Ironically the great Stoic died in a plague but because he was an Emperor the Antonine Plague was named after him. None of us, on the edge or not, would seek such a grim nomenclature. I am a mere Scottish poet, and my archaic instinct is that I want to fight this modern plague out in the open with spears and swords, dirks and claymores, beneath the hill, like ancient tribes who would ride out into the empty bog to fight the wind, who would burn bonfires on the top of Beinn Dorrery to greet the Spring. I want to bury this plague at sea. I want to summon up a storm and cover it in sand like the lost Coombs Kirk on Dunnet Beach, complete with its own crop of medieval plague dead, dancing now in the sand of history and in the eternity of time. I want to plough the plague beneath the earth, to burn it like dead heather on the hill, to shut it in a cave and roll a stone against its mouth.

I suspect it is not the virus that makes us afraid but rather our ill-informed opinions about it. Nor is it the inconsiderate actions of others, those ignoring social distancing, having house parties and driving to beauty spots miles from their homes, that make us angry so much as our powerlessness and insecurity which we project onto them. In other words it is not the individuals themselves but the reasons they do or do not do what is in the best interest of the human commonwealth, which we feel are a betrayal and diminish the majority. “Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers” as Wordsworth put it. These fraught days of Covid-19 can render talking and thinking into the babble of star-gazers. I hang onto the notion that the future is not destined to be worse, although that is likely. It is certain to be different. You cannot put a wall around infinity, no matter how scared you may be.

Epidemic is a Greek word meaning “on the people”, and until Hippocrates requisitioned it to refer exclusively to the spread of a disease, the Greeks applied it to anything that percolated through a population – from fog to rumour to civil war; and in our time – lying London Tories. We are told again and again, through the truth-portal of the BBC (other truth-portals are available) that the (UK) Government is “following the science”. As time goes on it is clear that the Government is picking and choosing what “science” suits it and that we, the people, are expected to follow the Government. Jerome Kim, the director general of the International Vaccine Institute in Seoul, said South Korea had contained the virus through “decisive and transparent leadership based on data, not emotion.” In “Britain” we are encouraged to clap our hands “for the NHS” and forget about decades of crippling cuts to all aspects of social care and civic infrastructure. When it comes to Westminster the question is – where does data end and ideology begin? Answer: every time a Tory minister opens their mouth in front of a camera or microphone.

In one of the stories in his 2005 collection “Here Is Where We Meet” John Berger has one of his characters say:

“I was scared of one thing after another. I still am. Naturally. How could it be otherwise? You can either be fearless or you can be free, you can’t be both.”

Walter Benjamin wrote that to be happy is to be able to live without fear.

As Berger reminds us, and as the present emergency shows us, that is not an easy condition to be in. One central challenge to those who dream of a better material future, post-Covid-19, is that everything in the world has been financialised. While the architects of this monetarised infinity take to their super-yachts to self-isolate, the rest of us are left to construct, somehow, from the broken pieces of free-market capitalism, a social model that protects us from “the fear and greed of mobs that trade”, as Sir Isaac Newton called the promoters of the South Sea Bubble scam in his day. These mobs are currently protected by governments and injected not with disinfectant but with what the US Federal Reserve calls “Quantitative Easing Infinity”, or “doing whatever it takes” so that the banks get bailed out yet again with electronic cash. The result is that instead of a financial system of reserve central banking with fiat currencies we have a hologram, an infinity of debt. For the ruling elite a return, post-Covid-19, to the old austerity cannot come fast enough. That is austerity for the majority and “business as usual” for them. Increased taxation for the majority whose income depends on work and the “good times” returning for those who flourish on tax avoidance, property, wealth and the ownership of everything that isn’t nailed down or can be looted. However there is a kink in this particular dialectic and it is this – as the world economy contracts, global debt surges. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) have said debt will increase by 13 per cent to reach 96.4 per cent of GDP this year. Global debts are the highest they have been since World War Two, at $250 trillion. As coronavirus burns its way through Africa and South America the infinity of debt will begin to consume the owners of the super-yachts.

Covid-19 is hitting every part of the world economy. The World Bank is warning of a devastating setback to the economies of Nigeria, Angola and South Africa, along with the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. Almost half the countries in the world – more than 90 so far – have been forced to apply to the IMF for financial assistance. Most of them will get nothing, or if they do the financial vaccination will be worse than the virus. The major weakness these countries have, their fatal flaw in the eyes of the World Bank, is that they are poor.

The nineteenth century French economist Claude-Frédéric Bastiat wrote that “When plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men in society, over the course of time they create for themselves a legal system that authorises it and a moral code that glorifies it.”

The result of that is that there are now two main ways to be broke: one, is you can have no money at all; the second, is that you can have all the money in the world and find out it is worthless. Cash that you do not have you cannot spend and cash that does not go directly into the economy has no value. Similarly there are two ways that the financial system will collapse: gradually and suddenly. We have witnessed the gradual graduation of things falling apart since 2008 and now in 2020 we see the systems fatal fragility with the latest crisis in the collapse of the price of oil. There will be others, one falling quickly on the back of another as assets become liabilities and each trader on the stock market floor goes in search of unobtanium, that mystic commodity which will save them from the infinity of debt. This way of life that is plunder, as Bastiat noted in the nineteenth century, we see both authorised and glorified now when the IMF, the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve continue to bail out the creditors and not the debtors. When the banks, as they have been doing, demand a bailout at the point of a gun that gun, as Anton Chekhov reminds us in literature, will be turned on them eventually. He wrote in a letter to a friend,

“If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”

The weapon of blackmail is “hanging there” and will be wrested from the sticky hands of the bankers and their advocates in governments around the world by the very people whom they exploit and have nothing to lose. This is why there is no going back to “normal”. Normal is fatal. Corvid-19 may be a coronavirus and it is a fact that it will kill anyone no matter where they are, who they are or how rich or poor they are, but as the grim statistics are doled out every day one thing becomes clear: the diseases of the rich kill the poor. In South America they call the coronavirus “La peste de los chetos – the plague of the snobs”. It makes its way into their lives off jet planes, cruise liners and tourist trains and leaves its red mark of death upon their doors.

As the writer Jonathan Cook has recently noted,

“Pandemics like this one are the outcome of our destruction of natural habitats – to grow cattle for burghers, to plant palm trees for cakes and biscuits, to log forests for flat-pack furniture. Animals are being driven into ever close proximity, forcing diseases to cross the species barrier. And then in a world of low-cost flights, disease finds an easy and rapid transit to every corner of the planet.”

“Little we see in Nature that is ours”, as Wordsworth lamented in his time. It is little wonder that pseudo-uber-shamans like Donald Trump, the Potus, conjures up cures from disinfectant and ultra-violet light when his government is producing magic money trees and an infinity of debt to protect itself from financial meltdown. So concerned are all governments to do likewise that they may decide to fortify this form of capitalism from their own electorate and treat the people as the plague, not Corvid-19.

It is not all doom, gloom, charity singles and clapping at eight o clock on a Thursday night. As the American writer and activist Rebecca Solnit has so brilliantly written:

“I have found over and over that the proximity of death in shared calamity makes many people more urgently alive, less attached to the small things in life and more committed to the big ones, often including civil society or the common good. There’s another analogy that comes to mind. When a caterpillar enters its chrysalis, it dissolves itself, quite literally, into liquid. In this state, what was a caterpillar and will be a butterfly is neither one nor the other, it’s a sort of living soup. Within this living soup are the imaginal cells that will catalyse its transformation into winged maturity. May the best among us, the most visionary, the most inclusive, be the imaginal cells – for now we are in the soup. The outcome of disasters is not foreordained. It’s a conflict, one that takes place while things that were frozen, solid and locked up have become open and fluid – full of both the best and worst possibilities. We are both becalmed and in a state of profound change.”

So we have to be hopeful, not frightened or scared. We may be “in the soup” but, as yet, we are not in the fire. But that does not mean that you should not look dreamily up at Venus and plan for a better world. We can reform our fragmented imaginations and in Scotland, at least, we can put forth the proposition that this pandemic, this crisis, shows beyond all doubt that we need to live in an independent country and we must all work everyday in every way we can to achieve that. It is, literally, a matter of life and death.

©George Gunn 2020

This is a brave and beautiful bit of writing. Some of the deepest and most useful thinking about the existential depth of what we are as yet barely aware that we are going through…

Your last two sentences perfect.

A thoughtful appraisal.

A wonderful piece of writing. Realistic, historical, cultured. One of the best things I’ve ever read on Bella. Thank you.

I was looking at Venus and the two day old Moon last night , as I have done since I first looked through a telescope in primary school at the age of seven.

Things seemed to take on a perspective that frosty morning and I have felt more an observer than a participant, watching the ebb and floe of world affairs and to see them scrambling about trying to work out how to use the situation to their advantage , putting their feet in it and being absolutely hopeless rings a bell through the last six decades I can remember. What changes , a Tory is still a Tory making the same noises fronting the ones in the shadows. Could say it was reassuring but it is not.

I agree, bring on Independence , the border is there for a reason.

Beautifully written essay but the human population on this blue planet is actually 7.8 billion.

Population increase this year (ie. the period of coronavirus) is over 26 million.

Take your point about the population. My apologies. Wrong number.

I hope Jonathan Cook meant that cattle are grown for *burgers*, not burghers. Unless, of course, that unfortunate industry has been wholly owned by the already far-too-wealthy German banksters?

Fine article, as are so many here…almost seems “damned by faint praise”, given the literary exuberance in these parts.

Aye, Daniel. Thanks, I didn’t spot the typo, but it is an amusing, if somewhat hellish, point you make.

I’ve felt that fear too George . But also sometimes a sense of peace and letting go. I love your writing.

Will the near-death experience of this pandemic make Scots more or less likely to take a risk and vote to live in a real country?

Lovely stuff ya wee wordsmith, ya.

In NY Governor Cuomo announces a 25% rate of antibody presence. In other words 1 in 4 New Yorkers have had coronavirus. This figure will go higher and therefore mortality rate will drop.

Expect much backtracking.

For some common sense and sanity amidst the coronavirus hysteria see Bill Maher interview with Dr David Katz. (Real Time with Bill Maher HBO)

It’s on YouTube.

Thank you again, George for your exceptional writing.

“‘Little we see in Nature that is ours’, as Wordsworth lamented in his time.”

Michael Newton in his invaluable dual-language book about the Gaelic heritage of my own home territory — ‘Bho Chluaidh gu Calasraid / From the Clyde to Callander’ — also quotes Wordsworth. Newton writes:

“Wordsworth wrote a famous poem when he was on Loch Lomondside:

Behold her single in the field

Yon solitary Highland lass

Reaping and singing by herself –

Stop here, or gently pass.

Alone she cuts and binds the grain

And sings a melancholy strain …

Will no one tell me what she sings?

Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow

For old unhappy far-off things

And battles long ago –

Or is it some more humble lay –

Familiar matter of to-day –

Some natural sorrow, loss or pain

That has been, and may be again?

“Rather than the feelings of the girl herself, the poem provides only the thoughts of Wordsworth. This symbolises the state of the Lennox and Menteith people generally – the opinions and literature of outsiders have taken precedence over the literature of the native inhabitants and the voices of the Gaels are now silent, as though they never existed. […] Despite that fact, we can state that until the nineteenth century the people of the Lennox and Menteith were every bit as Gaelic as the people of the Western Isles, and that remnants of the old Gàidhealtachd could still be found into the twentieth century.”

Newton states later in the book that indigenous Loch Lomond Gaelic survived until the 1950s. Grigor Labhruidh told me he puts the date into the 1970s.

Anyway, as a minor act of retrieval, here is my Scottish version of your quoted Wordsworth quatrain:

Tha an saoghal seo cus dhuinn; anmoch is tràth,

le sannt is cosg, thèid ar spionnadh mu làr;—

Cha lèir dhuinn san Nàdar ach tìr air fàs cèin,

Chaill sinn ar cridheachan, abair sochair gun stàth!

As always your writing inspires and comforts me. It’s so important and refreshing to read this when there’s so much drivel and nonsense flooding the print and airwaves at this time. It is a most welcome and necessary antidote. Thanks for your prose and poetry George it warms the ‘cockles of my heart’.

Brilliant, thoughtful, fully engaged and beautifully written. Your aven me on, stone the crows etcetera… Corvid-19