Just Doing My Job

I recently sat through a very dull talk opening a conference on some of the impacts of climate change. It was a classic example of academic pontificating, diffusing, hedging round the issues and eventually said so little that I began to wonder whether I might leave in the break. The next contributions were much more engaging so I stayed till lunch where I ended up in a conversation with the person who had given the opening address. This was a warm individual, passionate about the potential for their work to make a difference, who clearly cared deeply about the issue and talked compellingly about their alarm at the rate of change and their anxieties for their kids’ future. The contrast between the morning’s talk and the lunchtime conversation couldn’t have been more stark.

Academia’s ongoing battle (against the increasing evidence that this is ever fully possible) to present a rational, evidenced face is at odds with the catastrophe that is climate change. The person in this case, knew and felt the severity of the situation (and had established their department specifically to look at it), but even with (or maybe because of) their senior position, they seemed to feel unable to allow any of their human sentiment to come though in their public persona, hugely weakening their potential impact and concealing the power of their message.

This issue of scientific reserve has come under increasing scrutiny over the last few years as the terrifying scale of the climate catastrophe has been confirmed and there has been increasing pressure (and some progress) to encourage climate scientists to speak in more emotional, relatable terms about the subject of their research, to help non-scientists relate better to the core understandings – and their often very drastic implications.

Since my experience at the conference, I’ve noticed versions of this professional reserve on several occasions in very different contexts and have become increasingly convinced that this isn’t just a problem for scientists and academics, but is much more widespread, indeed it is a key piece in understanding why action on climate change has lagged so far behind what the science is telling us needs to be done.

At a recent event run by Scottish Communities Climate Action Network, we invited professionals from a wide range of sectors for a weekend retreat. The invitation, to attend as themselves rather than in their professional roles, was based on the experiences above and was an attempt to dig a bit deeper into the extent to which this change to the usual invitation would enable a different kind of communication. We observed that the people who attended engaged deeply with the content and shared opinions and feelings publicly that they acknowledged they had never shared at work before. One person, spending this time with a colleague they had worked with in other contexts, remarked that it was good to hear them for the first time being honest about what they really thought in relation to climate change.

In the hierarchical organisations most of us work within, it can feel unsafe on a number of levels to voice an opinion that runs counter to the status quo. Ultimately conformity is rewarded and while imagination and insight can also be valued in some fields or areas of work, they are often hedged round with sanctions for those who go too far. Employers often hold the ultimate sanction of dismissal for those who repeatedly refuse to conform to the ‘way we do things’ or who bring in challenges that are uncomfortable to those with more power.

This cultural reticence to stand out from the crowd is established deeply and early within the education system, where children are carefully schooled in giving the correct answers and in unquestioning obedience to those in authority. Time and time again, individuality, questioning, creative thinking and personal preferences and concerns are ignored or even punished, leaving students in no doubt that their personal opinions and values must be carefully trained to fit within a certain mould.

Continuing relatively unchanged from Victorian era values, the school system is where many of us have cultural colonisation drummed into us, most often by well meaning people who are simply (unquestioningly – because that’s built in too) passing on the cultural imprint that they themselves absorbed. School is the place where the work of personal and indigenous cultural suppression happens, where conformity to the rule of authority is embedded so deeply into us that most of us don’t even notice it’s there.

We’re told, and come to believe, that attending school is in our best interests. Clearly much useful teaching and learning happens there (although, many mistakenly believe that school is the only place that we can learn to do anything of value). But running deep and silent, alongside and intermingled with the range of school subjects, much of the medium, context, unspoken rules and values which underlie the education system feed into the (unconscious) perpetuation of the mindset of domination that enabled the ongoing colonial project: the objectification of anyone who is not a wealthy white male and the treatment of nature as a commodity rather than the miraculous basis for our species’ survival.

When those who tend to gravitate to senior positions in our workplaces are from the demographic most likely to deny climate change in the first place, it’s easy to see how, with the background most of us bring straight from school into work, creative thinking about a commensurate response is likely to be dumbed down, resulting in exactly the kind of tinkering round the edges that we have seen over the past decades. Those in power decide what is ‘realistic’ and most of us will fall into line behind that, even though realism exists to a great extent in the eye of the beholder.

This doesn’t stop at work: we moderate ourselves in many other ways, hiding or even denying emotions, ideas, dreams or beliefs we hold deeply, for fear of being seen as out of order, too much, strange. Protecting our vulnerabilities like this can leave us living less than our full selves. Most of us are much deeper, weirder and more interesting than we acknowledge to any but those closest to us. We hide our individuality, our specialness and our idiosyncrasies under a bushel of moderation which alienates us from our true selves and cheats others of the privilege of connecting deeply with who we really are.

In independent conversations, three researchers I know have told me that they, not infrequently, have strange experiences reported to them. These don’t crop up in the main interviews, but often just after, or in the pub later on, people mention personal practices, deeply held emotions or magical experiences. People are often reluctant to talk about such things, which they feel may mark them out as credulous, naive or unprofessional – and yet those experiences, responses, thoughts and feelings exist – and may be more genuine and appropriate than the measured, professional ones we have been socialised into.

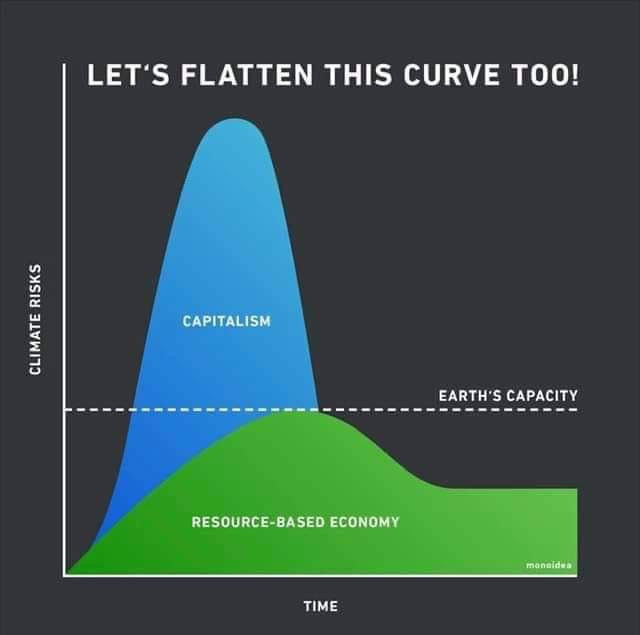

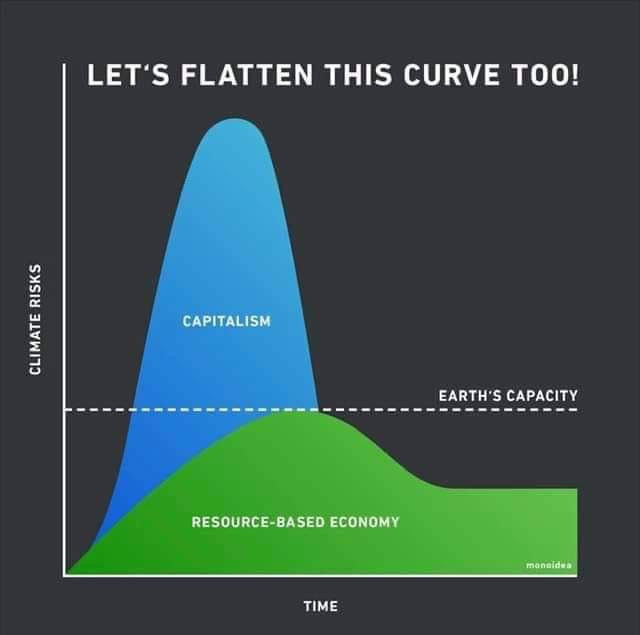

The range of potentially existential threats, including climate change, which are a direct consequence of the dominating mindset most recently expressed through neoliberal capitalism may only be able to be adequately dealt with once we have taken the risk to state the need for, and created enough safety to begin to unpick, the personal and cultural learned suppression of our true, idiosyncratic and interconnected selves.

Everyone’s experience of the lockdown is different – and for some it has clearly been catastrophic. One side effect for some has been that they are no longer tied to their work, or their work culture, in the same way as they were before. Might this rest from the ‘seeming’ many of us feel forced to do in the outside world, provide a wedge in the door that can resist a return to behaving as usual in the return to business as usual>

The relief we feel when we no longer have to pretend to be other than we really are will be echoed across the natural world, as we relax and put our energies into showering the love for ourselves, one another and the wider world that we are made for. This work of personal and cultural decolonisation needs our urgent attention.

Brilliant article Eva x

Every climate and biodiversity scientist needs to let that Jason Box “We’re fucked” moment out.

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vvb3pa/if-we-release-a-small-fraction-of-arctic-carbon-were-fucked-climatologist

I doubt that children simply accept the statement that attending school is in their best interests, and I don’t think the evidence supports that view. Are we to believe that the Curriculum for Excellence is “relatively unchanged from Victorian era values”? This can hardly be the case, or it would be hard to explain the attention given to dissenting movements like women’s suffrage in school, with the implications for today explored. Are children still being taught how to bear ‘the white man’s burden’? Or in fact, has the Horrible Histories approach made significant inroads and made state school defence of Victorian values impossibly imperilled by rightful ridicule?

A recent local newspaper summarised the most common family dinner table topics, and if I recall correctly *all ten* were environmental (OK, it might have been a throwaway piece, but the prevalence of environmental thinking and questioning amongst school-age children in the UK is surely beyond doubt). The popularity of programmes like David Attenborough’s various Life series are hardly down to his being an old, white male? And he is full of passionate views and anecdotes, and has reached out to modern-day school-age dissenters.

What would you replace school with? How would its socializing and levelling and mixing functions (outside of private cheat-education) be reproduced elsewhere? If you are going to do an article about science, I would expect more rigour.

Thanks, Eva, for your observations about the process of conformance that pervades schooling in Britain. I think this occurs even more in a University setting with a desperate scrabble to achieve high marks emphasising hierarchy over compassion as values normally supported – brilliance over mutual aid / competition over collaboration.

Can we truly listen to each other – and to our inner voices – at this time? Hope so!