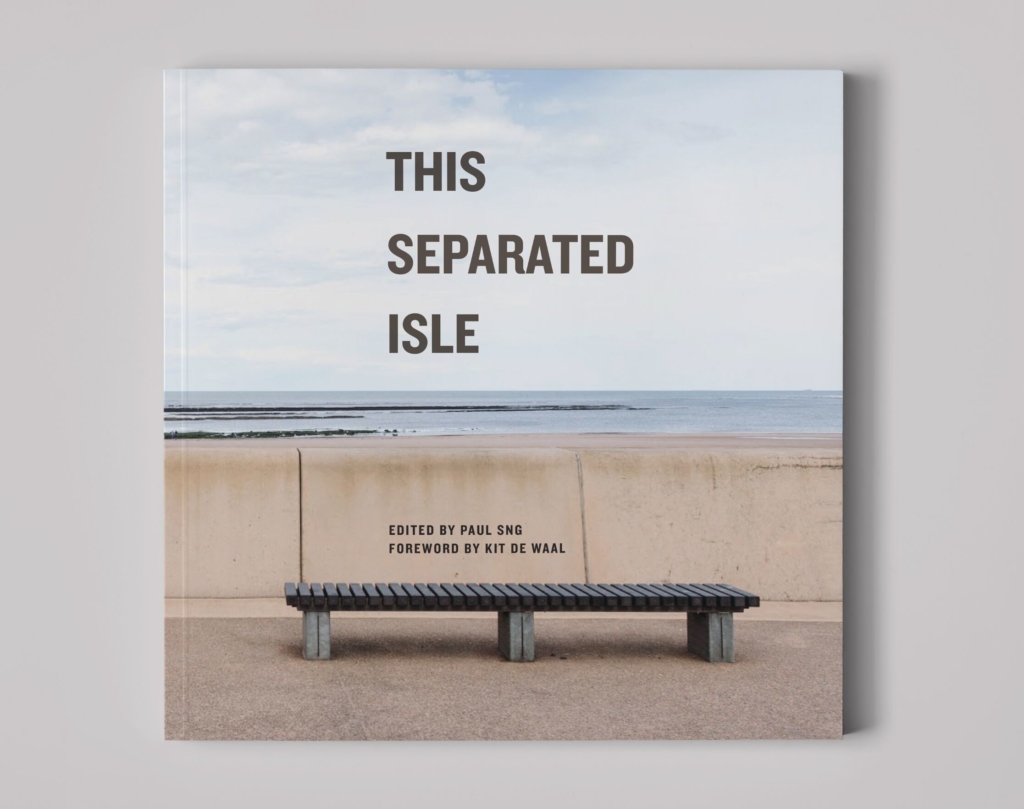

This Separated Isle

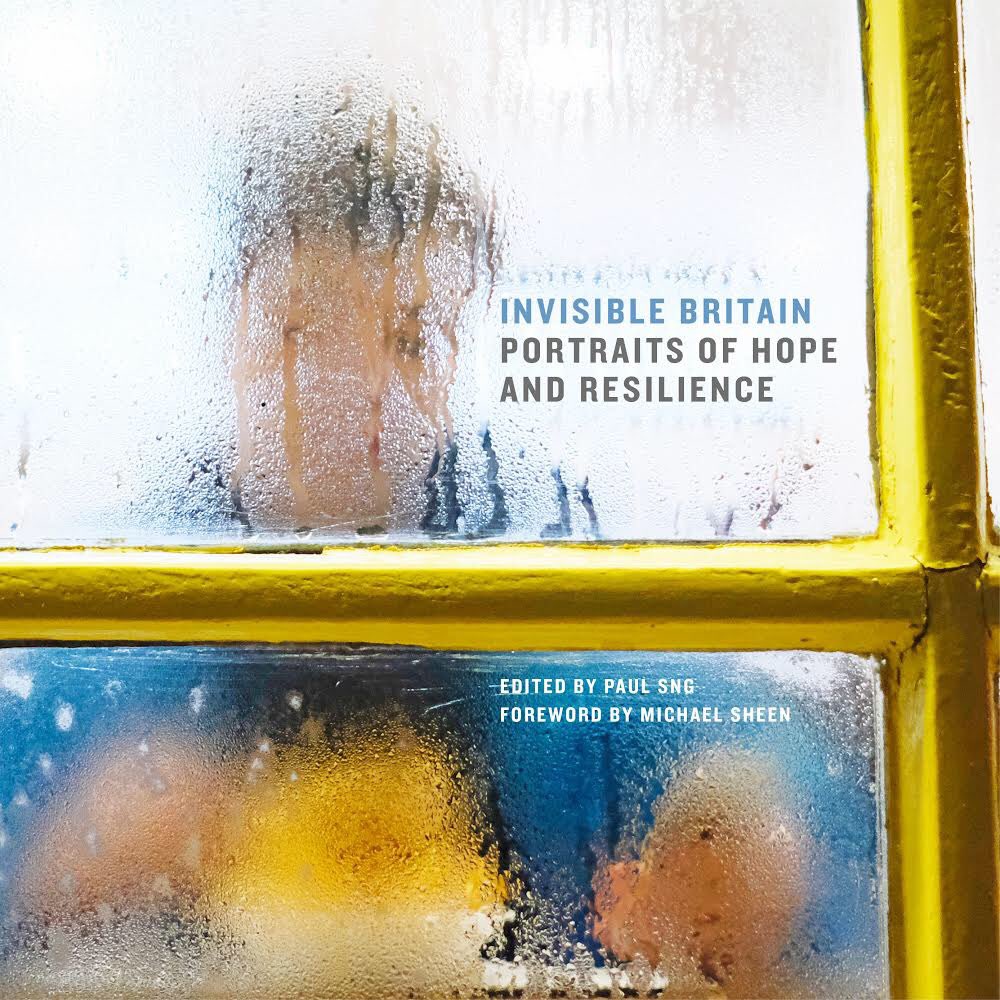

This Separated Isle is a forthcoming narrative photography book edited by documentary filmmaker Paul Sng, which follows on from the critically acclaimed Invisible Britain: Portraits of Hope and Resilience.

The book features stories and portraits of people from across the UK, and asks vital questions about the relationship between identity and nationhood to explore not only what divides us, but also the ties that bind us together – both in the past, and today.

In the UK and across the globe, the Covid-19 pandemic has made a seismic impact on society and how those within our communities who may be seen as ‘other’ are perceived. Yet even before this life-defining event, Brexit, the Windrush scandal, and rising levels of racial hate crimes all exposed bitter divisions in British society.

As we undergo the most turbulent period in modern times, This Separated Isle explores our concept of ‘nation’ and ‘identity’ via a diverse range of opinions and understandings about the meaning of ‘Britishness’.

The book combines direct testimonies with images shot by award-winning documentary photographers and emerging talents, to present a snapshot of modern Britain.

The photographers involved include: Alicia Bruce, Joanne Coates, Inès Elsa Dalal, Kat Dlugosz, Alecsandra Dragoi, Amara Eno, Mohamed Hassan, Mario W. Ihieme, Christine Lalla, Ciara Leeming, Jenny Lewis, Kathy Anne Lim, Sally Low, Gina Lundy, Kirsty Mackay, Margaret Mitchell, J A Mortram, Nicola Muirhead, Kate Nolan, Jon Pountney, Marie Smith, Roland Ramanan, Vivek Vadoliya, Fiona Yaron-Field.

Paul Sng is a documentary filmmaker whose work focuses on amplifying the voices of people who are rarely heard in the arts and media. His first book, Invisible Britain: Portraits of Hope and Resilience, was published in November 2018 by Policy Press. Sng will be working with a number of Scottish photographers and participants, we caught up with him to find out more.

It’s a daunting task and a huge challenge to present a credible representation of what constitutes national identity for a diverse range of people. The term ‘Britishness’ is problematic in numerous ways; there’s no universal definition of what it means. Ask an 80 year old woman in Glasgow to define Britishness and you’ll likely get a very different answer to that of an 18 year old in Glamorgan. As someone who grew up during the 1980s in London as mixed race and working class, my understanding of what it meant to be ‘British’ was limited to patriotic cliches and caricatures. It’s changed radically since then, but those traditional ideas still exist in some people’s minds and ought not to be diminished or disregarded just because they seem old-fashioned. The idea of the project is to hear from people of different ages, different ethnicities, different occupations and provide a broad range of what may even in some cases be contradictory viewpoints. Tolerance is a dreadful word when it comes to how we should treat people from non-western cultures who may hold different beliefs to the prevailing ones in our society. We should be aiming to understand and accept them.

Joy by Mario W. Ihieme

Scotland and England have been going through their own parallel ‘national identity’ crises in the last few years, does the project touch on this?

It does, yes. I moved up to Edinburgh from Brighton 18 months ago and my view on Scottish independence has changed in that time. I’d vote ‘Yes’ in the event of indyref2, though I don’t see it happening anytime soon. In the book we’ll be meeting several people who have their own complex relationships with England and Scotland, including Jack Tully, who spent his childhood and adolescence in London, but then moved to Glasgow to go to university and decided to stay there after graduating. His mum and dad are English and Scottish respectively, and he grew up supporting both Arsenal and Celtic. He’s never seen himself as English; he’s proud to identify as a Londoner and as Scottish. In football he would support Scotland over England, no second thoughts. I’m interested in those tribal affiliations and the reasons for why they develop.

Stina by Margaret Mitchell

What did you discover about the relationship between ‘identity’ and ‘nationhood’?

We’re still in the early stages of working on the book, but so far it’s clear there’s no specific formula across age, race, location that determines how someone understands their own relationship to identity and nationhood. Like most aspects of our character, we form views and opinions based on distinct personal experiences and encounters at key points in our lives. Some people choose to define aspects of their character, or even their personality, by virtue of where they feel that they belong. If you live in the UK and are from an ethnic minority, your relationship with identity and nationhood will likely be very different from someone who is white. And as someone from an ethnic minority, let’s say for example someone whose parents emigrated to the UK from Kenya in the 1960s, your ideas around the issue of British colonialism may differ too. Our relationship to visual symbols are also significant. The Saint George’s Cross is a prime example of a symbol that polarises opinion. Some people reject patriotism due to a perception that celebrating one’s allegiance to nationality can veer into jingoism. Others may find it anathema due to the connotations it has towards nationalism and the far right. I think both of those viewpoints can be much more nuanced than sweeping generalisations about flag-wavers or criticisms of people who dislike patriotic behaviour.

Susie by Kate Nolan

There’s multiple sub-cultures and identities that compete with a coherent idea of national identity, isn’t there? A European Gael, a Scouser, or people defining themselves by their class their sexuality or their racial identity?

It’s certainly tiered in terms of how someone may choose to identity, and again, it’s dependent on personal experience. Ask ten people a question about how they would define their identity and it’s doubtful that they would all have the same primary identifier, be it race/ethnicity, social class, gender, sexuality or regionality/location. And it would depend on how the question was framed. Regional identities may be more comfortable for some people, particularly in England. Embracing terms such as ‘Londoner’, ‘Northerner’, or ‘Mancunian’, for example, are easier for some people. I was born in London to a white English mother and a Chinese Singaporean father. I lived there for 30-odd years, but if you asked me how I identified, I’d say ‘Biracial British-Chinese Singaporean, working class man.’ I haven’t said, ‘I’m English’ since I was a kid. I don’t feel any great kinship to England or even London. Nice place to visit, lots of family and friends there, but I don’t see myself wanting to live there again for the foreseeable future.

Nina by Roland Ramanan

In my lifetime the idea of ‘Britishness’ has just collapsed, I don’t know anyone under 40 who would describe themselves as ‘British’, but then this is more problematic in England where inevitably an expression of identity becomes wrapped up in Brexit jingoism. What’s your understanding of this?

Absolutely. Brexit exposed bitter divisions within our society over notions of what constitutes British identity. I think those cracks have always been there, but social media has amplified opinions that view society through a prism of Them and Us, which is less concerned with who and what we are, than with who or what we are not. Sections of the media have at times presented lazy stereotypical representations of both Leavers and Remainers, which increases the disdain that each side has for the other. I voted to stay in the EU, somewhat reluctantly, as I felt it needed reform. I don’t think everyone who voted for Brexit was thick or ignorant. I can’t recall who came up with this, and it’s a bit simplistic, but I tend to agree with it: Not everyone who voted for Brexit is racist, but everyone who is racist voted for Brexit.

Maciej by Marie Smith

Can you tell us something about the commissioning process?

I worked with around a third of the photographers commissioned thus far on the first Invisible Britain book, and wanted to work with them again based on their interests and previous work as documentary photographers. We’re working with a mix of established photographers and emerging talents. It’s a good mix. I’m not interested in working with someone just because they’re a name photographer and have a big following. I like people to keep their egos in check and put the work first, respecting the participant and making the portrait with them. If our Kickstarter is successful, I’d like to secure some additional funding and commission another 6 photographers, with an emphasis on people who are under represented in the arts and media. At the moment, 25 out of 34 photographers are women, which is rare for a photobook.

The sub-title to the first Invisible Britain book is ‘Portraits of Hope and Resilience’ – but it does feel like a society, and four nations divided. Do you have much hope?

A Kickstarter campaign has been launched to pay for the book’s initial development costs and to cover the photographer’s fees. Funders may choose to select from a range of rewards in return for a contribution, including copies of the book and limited edition prints. If the campaign is successful the book will be published by Policy Press (a non-profit university press) in September 2021.

Follow the project here …

Kickstarter page: http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/invisiblebritain/this-separated-isle

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/invisiblebritain/

Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/invisiblebritain

Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/invisiblebrit

What does it mean to be British? I wish I knew now.

I used to know when I was about 9 years old. We were the good guys in all the “Commando” comics I read. Our British values of decentness and kindness towards the underdog were displayed in any film where “foreigners” were present.

There does seem to have been a notable increase in TV shows with the words “Great British …..” in the title. That is likely a sign of insecurity rather than security. All our best moments seem to have been during WW2, eighty odd years ago. We still drag them out the attic regularly to remind ourselves of when we were good.

We are a permanently warring, conquering, colonialising, rapacious, empire building nation. If these facts were more openly acknowledged in the story we tell ourselves, perhaps we could move on and become a more modern and sane state. I’d be interested to read the book.

Not surprising since it has been argued about since at least the 12th century.

Drawing on a book written by a friend on English music, the history of the word British is a complex and slippery one as is ‘English’. As early as the 12th century, Ealdorman Aethelweard announced that ‘Britain is now called England (Anglia), thereby assuming the name of the victors (nomen victorium)’. Yet Osbert Clare, prolific twelfth century writer, mourned the Norman conquest as follows: ‘And Great Britain [major Britannia] herself, wet with the blood of her sons, burdened with sins, succumbed to a foreign race, who despoiled her of her crown and sceptre… Therefore after the death of the glorious king [Edward the Confessor], unhappy England [infelix Anglia] sustained this disaster, and today suffers a degradation ruinous to the native English [innatis Anglis].’

Bloody Normans, coming over here, basically. Scotland (and Wales) were then an independent nations of course so Britain or British wouldn’t apply to any such lament / definition by default I suppose. But it does give a sense of the equating of British and Britain as words for the English and England, rather than Scotland and Wales, was there from very early, though for different reasons to what happened later.

I like the look fo this new book, thanks for the article.

This looks like an interesting book – I was born in London – mum was Irish and dad was Indian – my identity has always been a confusing issue to try and make sense of – I was a typical angst ridden teenager driven by my constant search for my own identity – I identify with London in a sentimental way because I grew up there until my mid 20s – I have lived overseas for the past 18 years and when someone asks me where I’m from I always say I was born in London – never “I’m English or British” – look forward to the book.

One of the obvious related questions that surprisingly isn’t discussed here much: What is Scottishness? Who classes as Scottish?