‘It’s the Buzz, Cock!’ – Love, Autonomy and Grassroots Music Venues in the Time of Covid

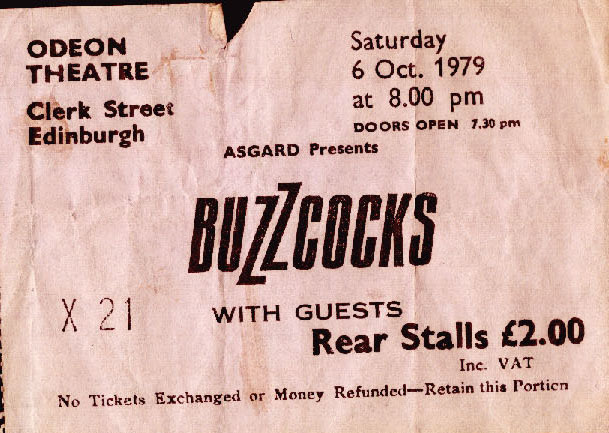

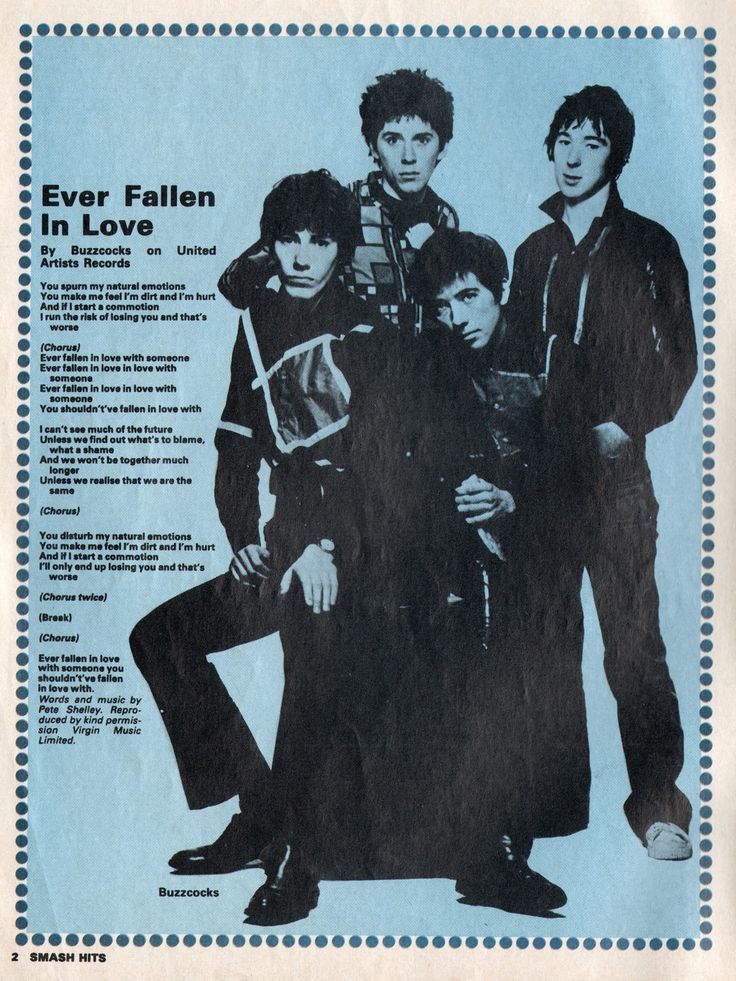

When Manchester pop-punk subversives Buzzcocks infiltrated the charts with their 1978 single, Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve), the song’s infectious true confession was a perfectly cynical display of unrequited love-lust. But the 2 minutes 40 second litany of gender-neutral spleen-venting was more than just a dirty secret laid bare. Penned by late Buzzcocks frontman Pete Shelley in a parked van outside Edinburgh’s main post office on Waterloo Place, the song’s resonance has trickled down the decades in a way that goes significantly beyond its original hormonally-charged intent.

Shelley’s breathlessly yearning lyrics set to an amphetamine-driven buzz-saw melody not only showed how artforms inter-connect and inspire one another during periods of social distancing and enforced isolation. The background to the evolution of Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) itself chimes with some very current concerns. These include the importance of grassroots music venues and a healthy small-scale touring circuit. The geographical location of the song’s composition also highlights the urgent need for arts funding for free-lancers and the benefits of a universal basic income for all.

Buzzcocks were on their first headline UK tour when Shelley was inspired by an old Hollywood musical to write Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve). It was November 1977, and the band had released their first major label single, Orgasm Addict, a month earlier after signing to United Artists that August. With the single housed in a sleeve designed by Malcolm Garrett and featuring a provocative feminist collage by artist and punk peer Linder Sterling to match the A-side’s title, Orgasm Addict was a bold pop/art statement that chimed with the prick-kicking times.

Shelly and original Buzzcocks vocalist Howard Devoto had taken their new band’s name from a headline in London listings magazine Time Out accompanying a review of ITV’s girl band based fringe-theatre styled 1976 TV drama, Rock Follies. The headline declared that ‘It’s the Buzz, Cock!’, and so it seemed to be, as Shelley and Devoto seized the means of production from the off.

After seeing the Sex Pistols in London, the pair brought the potty-mouthed agents provocateurs of punk to Manchester twice, with attendees at the two Lesser Free Trade Hall gigs that took place a month apart in the summer of ‘76 inspired to form bands themselves. That these included future members of Joy Division, The Fall and The Smiths is enough in itself to show how grassroots music scenes explode once a creative catalyst has been lobbed into the thick of things. It is also something that no state-sanctioned cultural strategy is ever likely to achieve.

When Buzzcocks’ Devoto/Shelley-led line-up released their self-financed Spiral Scratch EP on their own New Hormones label in January 1977, it kick-started a non-London-based indie record label revolution. Amongst many ‘regional’ imprints, those picking up Buzzcocks’ mantle included Alan Horne’s Postcard Records in Glasgow and Bob Last and Hilary Morrison’s Fast Product label in Edinburgh. The rest, be it through records by Orange Juice, Josef K, Aztec Camera and The Go-Betweens, or through those by The Mekons, Gang of Four, The Human League and Scars, or Fire Engines, Flowers, Boots for Dancing and all the others, is post-punk-funk-electro-pop/clash history.

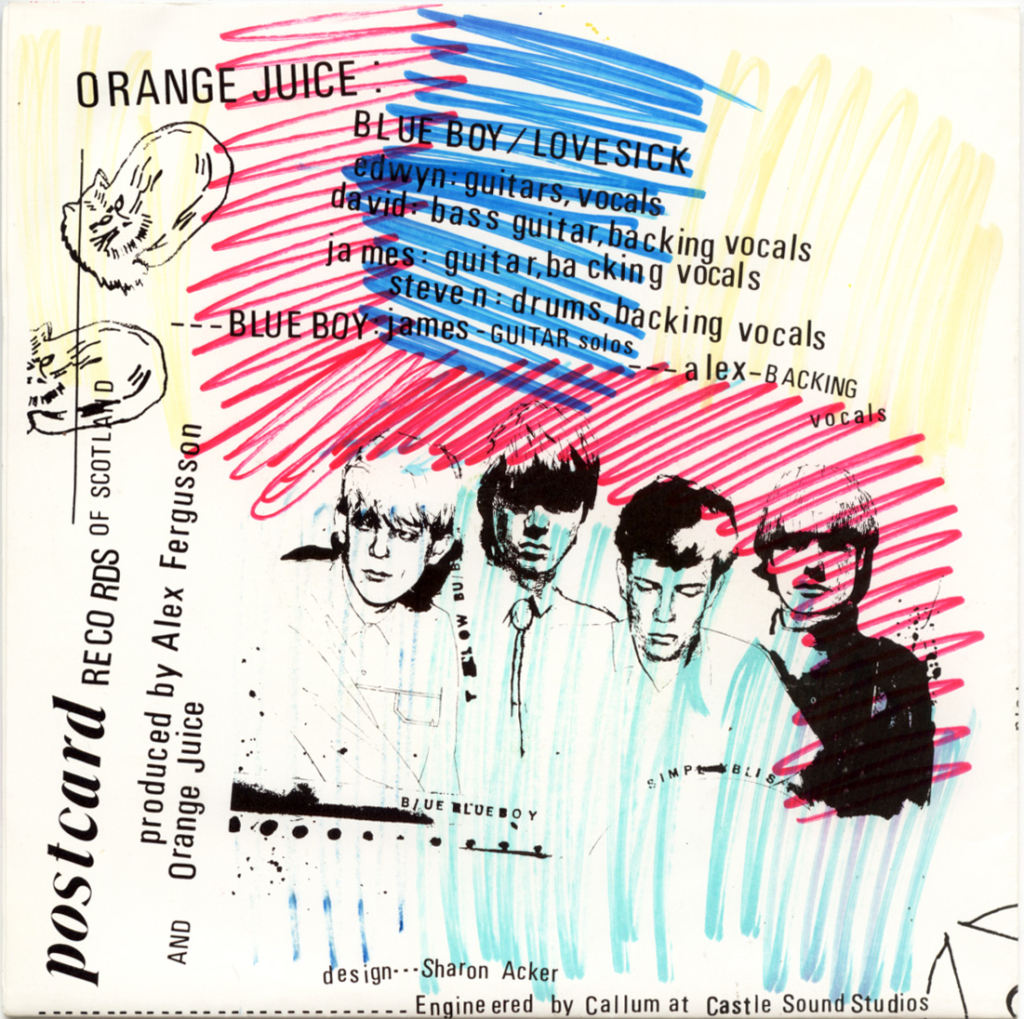

Buzzcocks’ influence trickled outwards musically as much as ideologically. Part of the opening riff and military style drum-roll of the band’s song, Autonomy, the B-side of their April 1978 single, I Don’t Mind, could be heard two years later on the intro of Orange Juice’s second Postcard single, Blue Boy. This was a song written by Orange Juice vocalist Edwyn Collins about Shelley. Orange Juice made their debt to Buzzcocks even more explicit in their 1983 chart hit, Rip it Up, on which vocalist Collins quoted two lines from Boredom, one of four songs on Spiral Scratch, declaring it to be his favourite song prior to co-opting the song’s two-note guitar riff.

Collins’ ‘Rip it Up and Start Again’ lyric went on to be used as the title for Simon Reynolds’ 2005 history of post-punk. The book told the story of Collins writing Blue Boy after meeting Shelley backstage at the Edinburgh Playhouse date of The Clash’s White Riot tour six months before Buzzcocks’ Clouds date. Rip it Up was also used as the name of the National Museum of Scotland’s 2018 exhibition on the history of Scottish pop and rock music. Claimed by both, Collins’ lyric about the desire to rewind a moment in order to be more articulate with the object of one’s affection had retrospectively become a clarion call for greater change beyond.

Meanwhile, those occupying the broadest of churches that is ‘the arts’ in Scotland are currently making their case to be included in the £10 million of ScotGov emergency funds and £97 million of Westminster money designed to support it during the Covid-19 crisis. With £2.2 million earmarked by ScotGov for grassroots music venues, Rip it Up’s co-opted implications of changing history, tearing down walls and kicking over statues sounds more pertinent than ever. If ever a slogan is required to propagate a proposed redistribution of wealth among free-lance workers by way of a brand new Year Zero, Rip it Up is there for the taking.

Most bands who released records on independent labels in Buzzcocks’ post Spiral Scratch day started out and sometimes finished either on student grants or the dole, Margaret Thatcher’s great gift to young creative upstarts. Up until the ‘90s, the dole was a rites of passage and a means to an end regarded by many as an unofficial arts council grant that allowed you to explore your potential. This was the case whether forming a band, starting a fanzine or starting a label or a club night that was part gang-hut, part arts lab.

Sometimes, Thatcher’s children were so grateful that bands even named themselves after the card required to sign on once a fortnight to ensure your Giro cheque arrived in the mail two days later in order to be cashed at post offices like that on Waterloo Place. As with many dole queue superstars, UB40 did quite well for themselves.

The labels were run from wardrobes and front-rooms in tenement flats, enabled for some by the Enterprise Allowance Scheme. This was a government-sanctioned sleight-of-hand that helped those on it to found small businesses, more often than not as free-lancers. The scheme also massaged the unemployment figures to look not quite as big as they actually were while bunging those taking part an extra tenner a week. This duly opened up would-be captains of what we now call the creative industries to the world of possibilities promised by a then burgeoning boom-or-bust free-market economy.

But Pete Shelley wasn’t thinking any of this when he wrote Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t Have) in a parked van outside Edinburgh’s main post office. Nor would he know that the building on Waterloo Place that then housed the post office would be rebranded thirty-odd years later as Waverley Gate. Here, residents of the building’s untouchably glossy offices would include Creative Scotland, the country’s arts funding quango formed out of the infinitely more approachable Scottish Arts Council, with extra added Scottish Screen thrown in.

CS was ill-conceived from the off, with the organisation’s first generously salaried chief executive’s tenure prompting a revolt by Scotland’s artistic community in 2012, before he wandered off to into the sunset to another overpaid post. His successor at CS met a similar fate.

Johnny Rotten’s contemptuous final public utterings as a Sex Pistol to a fawning American crowd spring to mind here. “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?” would have made an all too appropriate two-fingered epitaph to what at the time looked very much like The Great Creative Scotland Swindle.

Back in 1977, however, such top-down managerialist constructions were a long way off, and Edinburgh’s head post office was where a generation of wannabe artists went to cash their Giro. For young dreamers with no responsibilities to anyone other than themselves, the dole was a form of democracy in action, where everybody was paid the same, with few questions asked. And once you’d got through the initial inquisition, rather than fill in endless forms a la future funding bodies, all you had to do was turn up at High Riggs or Torphichen Street once a fortnight and sign your name.

Being a long-term doleite or else subverting the Enterprise Allowance Scheme back then was arguably a primitive equivalent of Universal Basic Income. This offered up the space and potential for everyone so inclined to become an artist, or at least to explore and experiment with what Joseph Beuys, the German iconoclast who Richard Demarco had brought to Edinburgh a few years earlier, called social sculpture. Finding a physical outlet for all that, alas, was an altogether different kind of tension.

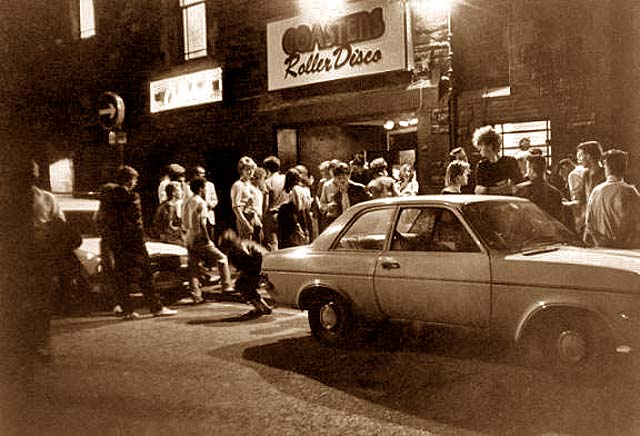

The night before Pete Shelley wrote Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) outside Edinburgh’s head post office building that would later become Waverley Gate, Buzzcocks played a venue called Clouds. This was in Tollcross, and was one of the key gig hang-outs during Edinburgh’s punk explosion.

Clouds originally opened in the 1940s as the New Cavendish ballroom, which was part of a thriving dancehall circuit that featured big bands. As music and social scenes changed down the decades, the venue adapted. Pink Floyd played there in the 1960s, while in the 1970s, local promoters Regular Music put on a stream of punk acts.

The venue later became Coaster’s, with the smaller second space housing the Hoochie Coochie club. As the club moved away from gigs, numerous other rebrandings followed, which at various points saw it become the Cavendish, Network, Outer Limits, Lava and Ignite and The Cav.

At Cloud’s, Buzzcocks were supported by Johnny And the Self Abusers, The Prefects and The Skids. Johnny and the Self Abusers would later morph into Simple Minds, while The Prefects begat Stewart Lee favourites, The Nightingales. Skids frontman Richard Jobson became something of a renaissance man as a film director and author, while guitarist Stuart Adamson went on to found Big Country. The various success stories that followed from each of these bands demonstrate the vital importance of venues such as Clouds. Bands and artists don’t come fully formed, and need spaces to play in order to develop.

Similarly, operations such as Regular need those places to put on gigs. Founded on hippy idealism and a DIY aesthetic, Regular are now Scotland’s oldest independent promotors, and continue to support grassroots venues and developing artists as well as larger events. Today’s equivalent of both Clouds and Regular require ScotGov support as much the new generations of artists they nurture. Without it, the big-name acts of tomorrow who might leave their mark on pop culture just as much as Buzzcocks have will have no space, time or money to do that developing. In the words of another Shelley lyric, they’ll have nothing left at all.

This goes way beyond the relatively recent problem of all-consuming gentrification closing down venues. The effects of Covid-19 pandemic could mean a total decimation of grassroots spaces that will undoubtedly be exploited to the max by the sort of predatory developers already hovering. Beyond the buildings themselves, the communities and social scenes that occupy them will be locked out for good.

One imagines many of the regulars watching Buzzcocks at Clouds to be either on the dole or in lieu of student grants in much the same way those on stage had been. These allowed their generation to indulge in pressure-free leisure time that enabled them to explore hitherto undiscovered ideas and assorted means of artistic expression.

With the relative short-term safety net of a dole cheque or a grant, they could do this in ways their latter-day peers are no longer able to. Instead, they’re more likely to be working off their student loans or else are forced out of the creative industries entirely for simply not being able to afford to be part of it. With today’s equivalent of Clouds looking set to struggle to survive in the era of socially-distanced events ahead, chances are that those wanting to will have nowhere to go, anyway.

The night before they played Clouds, Buzzcocks stayed in Edinburgh at the now long lost Blenheim Guest House on Blenheim Place. This wasn’t far from the Playhouse, where they’d supported The Clash that May with The Slits and Subway Sect as part of the headlining band’s White Riot tour.

With punk outlawed in Glasgow, it was the Playhouse show that provoked Scotland’s own musical revolution in much the same way the two Buzzcocks-promoted Sex Pistols shows had done in Manchester. The Blenheim was one of numerous businesses that exist around theatres and music venues who receive a boost from the association. As the current crisis has so cruelly proven, however, remove one card from a free-market pack, and the whole house comes tumbling down with it.

With presumably little in the way of local night-life to tempt them outdoors on a Thursday night – not for nothing did Kafka-inspired Edinburgh scratch-funk existentialists Josef K name their sole album The Only Fun in Town – Buzzcocks spent the night in the Blenheim’s bar. As documented in Tony McGartland’s book, Buzzcocks – The Complete History, originally published in 1995 and revised for a new edition in 2017, Shelley found himself in the guest house’s TV room half-watching the Hollywood film of hit Broadway musical, Guys and Dolls.

Guys and Dolls had been inspired by two short stories by Damon Runyon, whose baroque pen portraits of New York’s prohibition-era underbelly laid bare a world of gamblers, shysters and nightclub singers with comic relish. The musical was penned by composer and lyricist Frank Loesser, with a book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. It spun a yarn about hustlers Nathan Detroit and Sky Masterson, and their respective romances with nightclub singer and Nathan’s long-term fiancé, Adelaide, and leader of the Save-a-Soul Mission, Sarah Brown. Spoiler alert. Sky falls for Sarah after becoming embroiled in a $1,000 bet with Nathan to take her on a date to Havana.

The original production of Guys and Dolls opened on Broadway in 1950, and with a fistful of Loesser’s songs such as Luck Be a Lady, Sit Down You’re Rockin’ The Boat and Sue Me in tow, was a smash hit. The film version, written and directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, arrived onscreen five years later, and starred Frank Sinatra as Nathan, Marlon Brando as Sky, Jean Simmons as Sarah and, the only survivor of the Broadway production, Vivian Blaine as Adelaide.

As quoted in the Guardian in 2006, “We were in the Blenheim Guest House with pints of beer, sitting in the TV room half-watching Guys and Dolls,” said Shelley. “One of the characters, Adelaide, is saying to Marlon Brando’s character, ‘Wait till you fall in love with someone you shouldn’t have’. I thought, ‘fallen in love with someone you shouldn’t have? Hmm, that’s good.’”

The line comes from the scene in the film when Sky delivers Adelaide a message from Nathan, who fails to turn up for his and Adelaide’s planned elopement.

“Wait till you fall in love with somebody you shouldn’t,” is the actual line Blaine’s dejected Adelaide says to Brando. “Wait till it happens to you.”

Either way, Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) was the result the next day. Without so much as a Giro cheque, never mind a Creative Scotland grant, the baton had been passed, from Runyon’s short fiction to Loesser and co.’s stage musical to Mankiewicz’s starry Hollywood blockbuster, and now to Shelley and Buzzcocks’ punk-pop classic.

Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) would go on to be covered by Fine Young Cannibals, who scored a hit with it after it appeared on the soundtrack of Jonathan Demme’s 1986 film, Something Wild. A couple of years later, FYC vocalist Roland Gift appeared on the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in grassroots theatre company Hull Truck’s production of Romeo and Juliet at Marco’s Leisure Centre, not far from the sites of Clouds and Torphichen Street dole office.

A version of Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) by Pete Yorn appeared on the soundtrack of Shrek 2 in 2004. A year later, an all-star charity tribute to late DJ and Buzzcocks champion John Peel saw Shelley team up with unlikely bedfellows including Robert Plant, Elton John and Roger Daltry for an en masse version of the song designed to raise funds for Amnesty International.

Further covers included one from French loungecore trio Nouvelle Vague in 2006, while a version by actress Amanda Billing was a hit in New Zealand after it appeared in TV soap, Shortland Street. All this from Buzzcocks’ night in an Edinburgh guest house watching a Hollywood musical prior to a gig in a club called Clouds and some time out in a van parked outside the head post office that would later become the home of Creative Scotland.

This is how umbilical dots are joined up between artforms, and how, one way or another, the books read and the films and plays watched by latter-day artists playing today’s version of Clouds will rub off on them. Which is why all artforms – including those sired in grassroots music venues – should be treated as equals, especially when it comes to emergency funds for helping secure the survival of those affected by Covid.

If the new Year Zero is upon us and we really are going to rip it up and start again, as a show of faith and solidarity with freelancers, all high-salaried permanent staff at the top of arts institutions might also want to rethink their roles in order for things to be reimagined from a not so spiral scratch.

But those designated by ScotGov to distribute the £2.2 million made available for grassroots music venues in Scotland should tread carefully. Exactly how grassroots music and arts scenes are defined is up for debate, and freelance DIY auteurs and micro-based venues should be in the mix and arguing their small corner. All involved need to be careful too not to let purely commercial forces co-opt any notion of grassroots in order to monopolise the funds available.

With independent venues such as The Welly in Hull and The Deaf Institute in Manchester forced to close for good over the last few days, it is their equivalent in Scotland that need the support. These include dives such as Henry’s Cellar Bar, Leith Depot and the Voodoo Rooms in Edinburgh, the Glad Café in Glasgow and numerous others across the country.

With assorted working groups and task-forces already advising, ScotGov could do a lot worse than talk to those behind Glasgow-based record label, Last Night from Glasgow. Founded in 2016, LNFG is run as a not-for-profit on a subscription-based model, in which members contribute to decisions behind the label’s releases.

To date, LNFG has released more than 80 records, some of which were supported by Creative Scotland. LNFG’s DIY ethos both with records and promoting gigs by its roster of artists has arguably picked up the mantle of Buzzcocks, Spiral Scratch and the wave of independent record labels that followed in their wake.

Since lockdown, LNFG have been working on Isolation Sessions, a compilation album of the label’s acts covering songs by their peers. Funds raised from sales of the record will go to the assorted independent grassroots venues which were scheduled to host numerous LNFG gigs over the last four months. Such a show of solidarity shows how a music industry can retain a punk ethos in a supportive democratic environment rather than a competitive corporate one. The label’s faith in such an ethos seems to have paid off. In pre-sales alone, Isolation Sessions is already Last Night from Glasgow’s biggest selling record to date, and the possibilities for another music in a different kitchen are endless.

Beyond such grassroots idealism, and beyond Pete Shelley writing Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) in a parked van outside Edinburgh’s main post office where Giros used to be cashed in a building that would later be the home of Scotland’s arts funding body, there are plenty of other Buzzcocks song titles that fit the moment just now.

What Do I Get? is of course the question on every free-lancer’s lips, with Autonomy the ultimate goal. But it is that other freelance post-punk poet, Edwyn Collins, whose Buzzcocks inspired words sums up the moment. In terms of reinventing the arts from the ground up into something more democratic, now really is the time to rip it up and start again.

Details on support for grassroots music venues can be found from the Music Venue Trust at www.musicvenuetrust.com

Isolation Sessions can be ordered from Last Night from Glasgow at www.lastnightfromglasgow.com

Great article Neil. I remember introducing a couple of bands at clouds and meeting (albeit briefly) Siouxie of the Banshees. Such an atmosphere for gigs – really sorely missed.

Thanks Scott. Sounds great. Hope you’re well.

Searing stuff Neil just superb. I take art as above all somehow showing how everything’s connected or why it isn’t but should be and your piece does that to the Nth degree. I was a rebellious recipient of all you describe from back in that day and housing benefit was another absolutely key element of it all – the flats you could share in the centre of Edinburgh all paid for by the dole and Thatcher! That’s where ideas were hammered out that made all the glorious mess of an art explosion you describe so well.

I agree with all you say for today too. We need and must demand a grassroots led democratisation of the system – a UBI for freelance artists as the bottom line. Most of us are not looking for fortune or fame but just the chance to practice our crafts in relatively secure surroundings and not having to justify that craft to bureaucrats or business busybodies but to our peers and interested parties of the public. So come on Fiona Hyslop and Creative Scotland – make the imaginative leap and say that’s how it’ll be split, this dosh – by funding for a year as many freelance artists making work as possible. And then let those freelance artists inject life into as many of those empty buildings as possible and find their audiences if they’re out there.

Like you Neil ( and my ongoing collaborator Bill Drummond who also knows full well what all that back then was like and has no time for state-funded art ) I’ve major reservations about it all but making these demands of the cultural gatekeepers whilst keeping making art that aims to help make revolution, to rip it all up and start again is, as the line goes from that most idealistic of all songs Anarchy in the UK – it’s the only way to be.

Nice one, Tam. I totally agree. I’d forgotten about housing benefit. Their office was in Waterloo Place as well!