Seeing the Light – Andrew Weatherall, Denise Johnson and the Most Important Artwork in Edinburgh

Shona Hardie’s mural of Andrew Weatherall at Meadowbank, Edinburgh. Photograph by Tia Moore.

The sky was ablaze with light over central Edinburgh last Saturday night. On what would have been the opening weekend of the 2020 Edinburgh International Festival, the heavens weren’t lit up by fireworks, as is the norm at this time of year. Rather, the shafts of light that pierced the air were part of a spectacular installation designed to illuminate the city’s empty theatres and venues that would ordinarily be hosting EIF events this month.

Created by lighting designers Kate Bonney and Simon Hayes, aka Lightworks, the sky-borne spectacle was the flagship event of My Light Shines On. This is the name given to EIF’s digital programme of films taking place online throughout August in place of the physical events cancelled by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

The films showcase performances of commissioned works from Scotland’s national arts companies, including Scottish Opera, Scottish Ballet, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. Also online are works by Aidan O’Rourke of the band, Lau, a new composition performed by West African supergroup, Les Amazones D’Afrique, and a mini gig by Honeyblood, aka indie grunge chanteuse, Stina Tweeddale. Pieces by the Hebrides Ensemble, the Traverse Theatre and others are pending. Each film was made in otherwise empty venues under social distancing guidelines. All are free to watch on EIF’s YouTube channel throughout August.

Arguably the most striking contribution to My Light Shines On thus far beyond Bonney and Hayes’ installation is Ghost Light. This 30-minute film by Hope Dickson Leach was presented by the National Theatre of Scotland, and takes its cue from the tradition of keeping a solitary light aglow in theatres when they’re closed.

As it burls its way backstage in the Festival Theatre, it weaves together a cinematic collage of bite-size excerpts from NTS greatest hits past, present and possible. These include JM Barrie’s Peter Pan, John McGrath’s era-defining The Cheviot, The Stag and the Black, Black Oil, plus more recent works by the likes of Jenni Fagan, Hannah Lavery and Jackie Kay. In its presentation, Ghost Light also celebrates the work of theatre’s key workers; the backstage staff, cleaners and programme sellers without whom theatre wouldn’t function.

As an attempt to shore up the loss of live events, EIF’s My Light Shines On programme is delivered with love and care. It also provides employment for many whose already insecure livelihoods have been seriously under threat since lockdown.

One of the many things lockdown has exposed is that the so-called ‘creative industries’ remains a top-down construction, with the catch-all ‘creatives’ scrambling for economic security at the bottom. The scale of recent redundancies of arts-based key workers is en route to decimating the entire sector. The UK government’s willingness to throw freelance workers of all kinds under a bus that probably isn’t running anymore as there’s no-one left to drive it confirms a social divide that only the urgent implementation of Universal Basic Income will go some way to address.

My Light Shines On takes its name from a lyric from Primal Scream’s song, Movin’ on Up. The song opened the Glasgow-sired pop/punk/psych/soul pick-and-mix magpies’ lysergically charged 1991 album, Screamadelica. As a call to arms for the musical and spiritual salvation Screamadelica’s melting pot of indie-dance-dub-hedonism so swaggeringly epitomised, the euphoric anthem remains a joy.

While Movin’ on Up’s vocal is led by Primal Scream vocalist Bobby Gillespie, key to the gospel choir flourishes that take over its second half is the voice of Denise Johnson. Johnson is the Manchester-born singer who fell in with Primal Scream after they saw her sing live with rave era duo Hypnotone at DJ Danny Rampling’s pioneering acid house club, Shoom.

Johnson spent five years with Primal Scream, providing vital contributions to Screamadelica and its follow-up Give Out But Don’t Give Up. She also provided sass and soul to the many other bands whose records she appeared on. These included New Order and A Certain Ratio. She was part of the latter for more than 20 years, last appearing with the band in Edinburgh at the city’s Voodoo Rooms venue in June 2019.

Johnson also appeared solo in Edinburgh twice. That was in 2018 and 2019 at Neu! Reekie!, the capital’s premiere spoken-word, music and experimental film shindig. At these shows, Johnson showcased songs from her forthcoming solo album, Where Does it Go, including a stripped-down cover of New Order’s song, True Faith.

For all Johnson’s array of collaborations, it is likely she will forever be in part defined by her work on Screamadelica. She will have sung the line, My Light Shines On, many times live.

A few days before EIF’s My Light Shines On initiative was announced, the sad news of Johnson’s passing aged 56 made waves across the world. As a black British woman from a working class background working amongst the boys club music industry, Johnson was so often mistakenly regarded as ‘just’ a backing singer, but she was so much more. As anyone who saw or heard her, Johnson’s voice, presence, attitude and soul helped transform every song she sang into something special.

Movin’ on Up was produced in Memphis by Jimmy Miller. It was one of few tracks on Screamadelica not to have been overseen Andrew Weatherall, the maverick sonic alchemist who passed away in February this year, also aged 56. Weatherall produced or co-produced most of Screamadelica, and was as key to the record’s success as Johnson was. One of its highlights was Don’t Fight It, Feel It, which featured Johnson on lead vocals. It was for this song that Primal Scream went looking for a singer other than Gillespie at Shoom, where Weatherall also DJed.

By that time, Weatherall’s audacious reconstruction of a song from Primal Scream’s eponymous predecessor to Screamadelica looked set to take both the band and the then underground dance culture into the mainstream. That was with Loaded, which took the strung-out slow blues of I’m Losing More Than I’ll Ever Have and, using a diverse array of samples, cut and pasted it into the era-defining anthem it became. Weatherall also produced the ten-minute-long Screamadelica, which didn’t appear on the album, but as the final track on the Dixie-Narco EP, the lead track of which was Movin’ on Up.

Beyond Screamadelica, Weatherall continued to reinvent modern music as we know it, both with his remix and production work with the likes of One Dove, Saint Etienne, My Bloody Valentine and Bjork, and in his own right with The Sabres of Paradise, Two Lone Swordsmen, and more recently under his own name. Weatherall appeared in Edinburgh many times, and in 2019 he and Johnson shared a bill at Neu! Reekie! Founded by writers Michael Pedersen and Kevin Williamson, the night’s roots in the sort of punk/dance speak-easy vibe both Johnson and Weatherall helped foster made them an ideal double bill.

Like Johnson, Weatherall was a self-taught music obsessive. A Windsor-born fanzine writer schooled in northern soul, he applied his instinctive cut-and-paste aesthetic and impeccable taste to the burgeoning new dance culture. Like many of his rave generation peers, Weatherall’s use of sampling was crucial. With cheap technology at his fingertips, mixing and matching these musical cut-ups became an artform in itself.

In clubs like Shoom, the results fostered a transcendent live experience. Rather than occupy a formal theatrical space where passive spectators watched a band play behind the fourth wall, Weatherall became a Prospero figure, magicking the dance floor into a participatory communal spectacle. Buzzword-friendly on-trend theatre-goers might call this immersive. Either way, Weatherall’s counter-cultural canon remains as rooted in Dionysian bacchanal as anything the Greeks managed, and his art was just as high. Higher than the Sun, perhaps, with extra added dub.

Within a day of Weatherall’s passing in February, a mural of his image appeared in Edinburgh on the hoardings beside the building site for the new Meadowbank sports stadium. The portrait showed Weatherall’s floating visage – beatific and bearded – peering out from the cosmos against a backdrop of stars. It was a stunning tribute, made all the more so by the fact that it had appeared overnight in a guerrilla style action that was in keeping with the original underground ethos of the club culture that drove Weatherall’s work.

Within hours, the image of Weatherall filtered out across the internet, and was reported across the world. The reports revealed that the painting was by Shona Hardie. Hardie is an Edinburgh-based artist, whose distinctive purple washes and starry starry nights light up various sites around town if you look hard enough. She is one of a tight-knit community of street artists, whose spray-painted largesse graces spaces such as the Meadowbank hoardings, which provide a platform for artists that helps beautify the neighbourhood while the building site behind it continues on the road to gentrification. It’s how cities work.

The Meadowbank site hosts a mix of work by local school-children and art students, advertising hoardings and an ever-changing array of mind-expanding murals.

You have to get in there quick, mind, before they’re painted over as part of a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it aesthetic that goes with the transitory territory. Some are painted over in days, living newspapers delivered with quick-fire headlines. Others, like Hardie’s portrait of Weatherall, are left a while longer.

At time of writing and more than five months after it first appeared, Hardie’s mural of Weatherall has survived. This is a testament to both the power of Hardie’s artwork, and to the influence her subject has had on the grassroots club culture he was part of and continues to inspire.

Since the end of July and throughout August, the Meadowbank site is being used by Edinburgh Art Festival to host new poster works by Ellie Harrison and Ruth Ewan. These form part of what is mainly an online programme, but which has also moved into public spaces following the closure of permanent galleries and any potential for pop-up sites that might have been used.

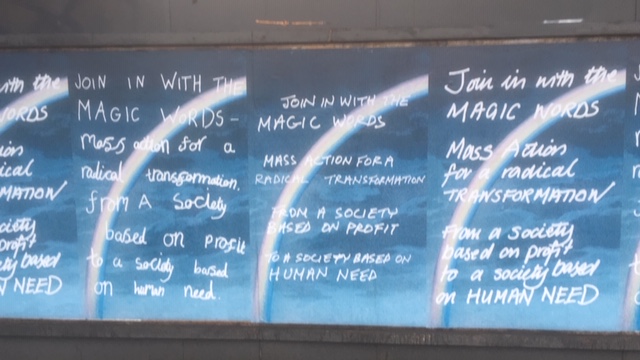

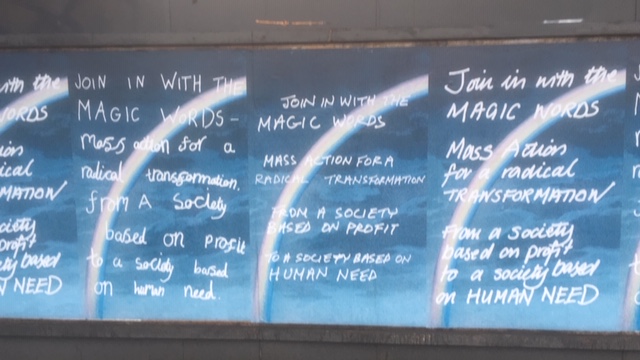

Ewan’s poster, Magic Words (Ian, Margaret, Peggy) (2020), takes a phrase coined by socialist magician Ian Saville as part of his act. Rather than a tried and tested ‘abracadabra’, Saville’s magic words call for ‘mass action for a radical transformation from a society based on profit to a society based on human need.’

Reproduced as written down by Saville, Ewan’s mother and her 7-year-old daughter, it proffers a cross-generational call to arms. The poster forms part of Ewan’s Sympathetic Magick project, which also features her short film, Worker’s Song Storydeck (2018), in which close-up magician Billy Reid lays out an entire history of working class strife set to a Dick Gaughan soundtrack.

Harrison’s poster, Tonnes of carbon produced by the personal transportation of a ‘professional artist’ (2020) is a graph of the artist’s carbon footprint on trains and boats and planes over the last 17 years. Harrison compiled the work while writing her book, The Glasgow Effect: A Tale of Class, Capitalism & Carbon Footprint. This came out of The Glasgow Effect (2016), in which Harrison didn’t leave the boundaries of Glasgow for a year. This attracted considerable attention at the time, and might now be read as an accidental dress rehearsal for lockdown.

Just as Johnson’s passing has accidentally heightened her unspoken presence in Edinburgh International Festival’s My Light Shines On programme, so Hardie’s mural of Andrew Weatherall seems to fit with the grassroots DIY spirit of Ewan and Harrison’s work. This is despite it not being part of Edinburgh Art Festival. Casual passers-by could be forgiven for presuming otherwise. While the relationship between work by Hardie, Ewan and Harrison and their immediate environment in Edinburgh is the same, they are equal, but different.

In this sense, both Johnson and Hardie’s presence might be considered acts of accidental artistic infiltration. This raises the question of whether any kind of formal institutional recognition is necessary for such artworks that exist outside Edinburgh’s festival bubble.

All this is before we even start thinking about the Scotland-wide Black Lives Matter Mural Trail, a bold and brilliant public art programme instigated in June 2020 by creative producer Wezi Mhura following the killing in America of George Floyd. At time of writing, some 18 new BLM inspired artworks are on display outside theatres and arts venues. 13 of these are in Edinburgh. With more pending around the country, the project requires a stand-alone study in its own right.

My Light Shines On is a lyric to a song that appeared on a record fired by underground club culture. It was a culture that was greeted with hysteria by an establishment that saw young people communing together within earshot of repetitive beats as an ideological threat to civilisation as they knew it. Using the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, the UK government of the time formally tried to outlaw rave culture. For that hedonistic ethos to be embraced by a festival that now recognises its worth is part of a more enlightened generational shift, ageing ravers notwithstanding.

Just as Screamadelica was created by Primal Scream, Andrew Weatherall and Denise Johnson and bank-rolled by a commercial record company without any kind of arts council grant, Hardie’s mural of Weatherall was created organically and instinctively. Unlike anything in EIF and EAF, it wasn’t commissioned or developed by a publicly funded institution or agency. Nor is it required to tick any boxes for well-meaning government arts strategies. There is no expensive PR company hyping up Hardie’s work in the glossy magazines. All the attention her mural has received is from word of mouth, and didn’t cost a penny.

Again, this raises questions about what is or isn’t included in institutional arts worlds, and points to how those outside those institutions relate with them. Should Hardie’s painting be acknowledged in a festival that is making a genuine effort to use public art as a platform now Covid-19 has temporarily closed the permanent galleries and potential pop-ups? And should it be recognised by a national institution – the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, say – as acknowledgement of its brilliance as one of the most significant public artworks in Edinburgh, as well as for the culture Hardie’s subject represents? Or would bringing her work in off the street change how it is regarded, somehow, and make it less cool?

But Weatherall’s own art was as high as any other boundary-pushing iconoclast, remember. As a musical collagist, his sonic cut-ups were the equivalent of the sort of Dadaist experiments novelist William Burroughs looked to for his own literary adventures.

Weatherall’s fusion of beats, rhythms and loops could easily have sat in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s Cut and Paste exhibition of collage-based work that ran in 2019. His back catalogue would have sounded great in a room alongside Sticky Fingers (2010), a Rolling Stones inspired work by Jim Lambie, the long time peer of Bobby Gillespie who provided the cover art for Primal Scream’s 2013 album, More Light.

Should street art like Hardie’s mural of Weatherall embrace its here-today/gone-tomorrow temporary lifespan and be painted over? If so, only the unreliable memory of those who witnessed it would be left behind to immortalise its spirit, just as they might after a night at Neu! Reekie! listening to Weatherall and Johnson.

The institutional need to monumentalise things suggests otherwise. Street art like that produced by Hardie has long been accepted as legitimate in its own right. The late Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat respectively used the New York subways and building walls as their canvas during the late 1970s and 1980s en route to commercial success before their careers were cruelly cut short. Both artists too were rooted in grassroots pop and club culture as much as social and political concerns. More recently, Banksy’s provocative street interventions have taken art into the public arena in a way that continues to make both headlines and money.

If work by Haring, Basquiat or Banksy were to be shown at Meadowbank, it would be lauded as a major event. Given the global recognition of Hardie’s mural of Weatherall, albeit in dance music magazines rather than coffee-table art tomes, her work is arguably already up there with them. Ewan and Harrison too should be regarded as Hardie’s peers. With such a rich tapestry at play, why shouldn’t her work be formally recognised?

Either way, for now at least, Hardie’s mural of Weatherall is still with us. It’s been peering out at the world’s absurdities all the way through lockdown, into festival season and hopefully beyond. With Weatherall a celestial cosmonaut of both inner and outer space, it’s easy to imagine Denise Johnson’s voice lighting up the stars that shine behind him even more. So, go on. Don’t fight it. Feel it.

Shona Hardie’s mural of Andrew Weatherall can be seen at Meadowbank Stadium hoardings, Edinburgh as long as it lasts. Other work by Hardie can be seen at www.shonahardie.com

Where Does it Go by Denise Johnson is scheduled for release on September 25th.

Details of the Black Lives Matter Mural Trail can be found at www.wezi.uk/blm-mural-trail

Edinburgh International Festival’s My Light Shines On programme of films can be seen at www.eif.co.uk until August 28th.

Edinburgh Art Festival’s online programme can be viewed at www.edinburghartfestival.com until August 30th. Details of the Around the City programme by Ruth Ewan, Ellie Harrison and others can also be found there.

Image credit Denise Johnson photo: Kat Gollock

Movin on up was mixed in Memphis but recorded and produced in London, I seem to recall at Miloco.

Most of the production team (apart from Mr Jimmy) were managed through Jazz Summers and Tim Parry’s “Big Life Music Mgt” out of Manchester.

Thanks for that detail, Bruce. Much appreciated.

Denise was a brilliant musician,got to know,her when we both started out on the Manchester music scene,

She was also a friend,,our common bond ,we were both singers in a male dominated scene,so having another girl to chill with was good,

She was great company,funny ,dry,we would talk Man City, politics ,and music,it was great to have someone as much a trainspotter as me

With regard to vocalists,we d tweet all the time,I miss her,

I am at the moment writing a book about the Manchester music scene,

I have included all the girls I meet on the way ,1974 onwards,Denise is there,in spirit,I hope,to show how important the girls

Were ,because it’s always the boys story, x

Thanks for your comment, Ann. Denise was really special.

I saw you sing with The Swamp Children at a couple of Liverpool shows with ACR, then later in Edinburgh with Kalima, and I have your records.

Very much looking forward to reading your book.