Bad Poetry Day

It would seem that someone, somewhere has the job of thinking up suitable days upon which to celebrate or commemorate obscure subjects. Mothering Sunday becomes Mother’s Day; spawning the spurious Father’s Day, which is, let’s face it, nothing much more than a marketing ploy. On August 18th we are solemnly to worship at the altar of ‘Mail Order Catalog Day’. The first Mail Order Catalog was apparently issued in the USA on this day in 1872. Hence the spelling.

It would seem that someone, somewhere has the job of thinking up suitable days upon which to celebrate or commemorate obscure subjects. Mothering Sunday becomes Mother’s Day; spawning the spurious Father’s Day, which is, let’s face it, nothing much more than a marketing ploy. On August 18th we are solemnly to worship at the altar of ‘Mail Order Catalog Day’. The first Mail Order Catalog was apparently issued in the USA on this day in 1872. Hence the spelling.

Serendipitously, August 18th is also Serendipity Day.

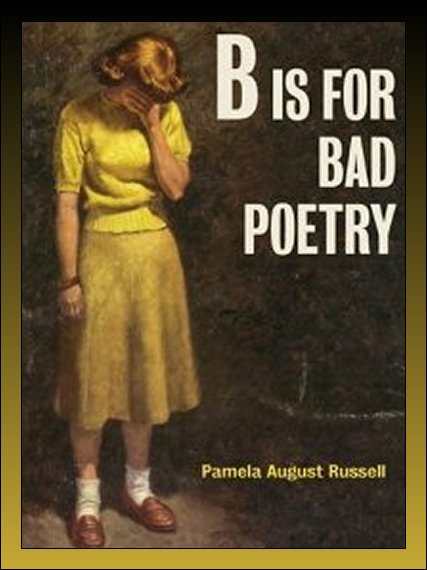

More significantly, perhaps, and with artistic significance of international proportions, August 18th is BAD POETRY DAY. The purpose of the day seems to be to promote an appreciation of great poetry by encouraging people to expose themselves to the sub-standard stuff: read McGonagall and you’ll appreciate much more the artistry of Robert Burns. Better still, write some poetry yourself and your powers of self-criticism will demonstrate to you just how far your work falls short of that of the Masters.

And that might show you how to improve.

Or persuade you better to appreciate the skills and artistry of the Greats.

For self-criticism to be effective, however, don’t we need a proper set of standards against which to measure ourselves?

Well, it depends, probably, on what we’re writing poetry for. The jury is still out concerning the extent to which William McGonagall was aware of his own shortcomings. He gave readings, apparently, at which the audience would habitually pelt him with eggs, and this seems to have been an aspect of the entertainment in which he willingly participated. To a limited extent he made money from his work; and his work involved public humiliation.

On one occasion, however, he walked from Dundee to Balmoral because he imagined Queen Victoria would want to hear his stuff. Palace officials told him that Tennyson was quite good enough for her Maj, and the poor fellow had to walk all the way home again. It seems likely that McGonagall was on the autistic spectrum, so self-criticism may have been difficult for him. But if his ambition was to find lasting fame through his work, one cannot deny that he succeeded.

Some people play the recorder brilliantly, and make beautiful music with it (for example, youtube Lucie Horsch). Most of us, however made nasty noises on plastic toys at Primary School and now think that the recorder is, at best, a joke. We fail to appreciate that the recorder was chosen in this role because they are real instruments which are not too challenging to start with, and which are an appropriate size for little hands.

Something similar happens with poetry. The recent success of the TV series ‘Killing Eve’ has sparked the renascence of the word Villanelle. Even so, most people are unaware that a villanelle, strictly speaking, is a fixed-form poem of nineteen lines consisting of five tercets and a quatrain, using only two rhyming sounds and a pattern of two refrains. I refer you to Dylan Thomas’s ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’.

Could you write something like that?

Maybe not.

Had you even realised, knowing the poem, how effortlessly complicated it is?

Probably not.

Could you persuade a class of ten-year old Primary School kids to attempt such a thing?

No.

Let’s get them to do a Haiku instead.

Of course a haiku can be beautiful, meditative, epigrammatic, arresting, enigmatic and profound. Its basic form, however, is so simple, that there are haiku generators online, and the producers of Pointless think that by writing questions that are seventeen syllables long they are cleverly framing them as haikus. More to the point, perhaps, they are tolerably easy for teachers to explain to rebarbative semi-literate munchkins. They are the literary equivalent of the recorder.

So why bother with a villanelle if a haiku can be wonderful? There are many reasons why different verse-forms might be differently appropriate: Wordsworth and Coleridge were seduced by the beguiling simplicity of folk poetry when writing ‘Lyrical Ballads’; William Dunbar seems to have sustained the moribund form of alliterative verse so he could make use of its percussive, rhythmic intensity; the oxymoronic structure and variety afforded by Rhyme Royal attracted Chaucer and Henrysoun to their Troilus and Cressidas; while W.B.Yeats completely subverted both epic poetry and the love sonnet by fitting the whole of the Iliad into the fourteen lines of ‘Leda and the Swan’.

The marriage of form and content can be exhilarating. When skilfully done it enhances the meaning, the emotional power of the lyric. The Great American songbook, for example, was built on the sheer bloody satisfaction delivered by the craft of lyricists. Consider:

Grab your coat and get your hat,

Leave your worries on the doorstep,

Just direct your feet

To the sunny side of the street.

Can’t you hear a pitter-pat?

And that happy tune is your step,

Life can be so sweet,

On the Sunny Side of the Street.

(Dorothy Fields)

It doesn’t set out to be great poetry, it sets out to be a popular song; but there is something joyous in that rhyming of ‘your step’ with ‘doorstep’; with the ambiguity of ‘pitter-pat’ (is it rain? Is it tap-dancing?); and with how nicely Dorothy Fields has extended the metaphor. When it joins the tune there is an effortlessness about it which is life-enhancing.

Making use of any poetic form imposes a tension which is relieved by a successful outcome. Take rhyme: ‘step’ could rhyme with ‘pep’, but doorstep has a so-called feminine ending (the stress falls on the first syllable), so although one might lazily attempt to rhyme ‘doorstep’ with eg. ‘two-step’ it doesn’t really work. ‘Door’ doesn’t rhyme with ‘two’, and step doesn’t rhyme with ‘step’ because they are the same word. When one listens to the song being sung one’s subconscious registers that ‘doorstep’ will need a proper rhyme, and that that rhyme won’t be obvious. This creates tension. When the words ‘your step’ arrive there is a recognition that it is a rhyme which works cleverly and appropriately, and this delivers a little emotional release. The form itself has wound you up, and then let you go.

In 2017 that internationally renowned fast driver of fast cars (and fast-and-loose tax-avoidancy techniques) issued a poem commemorating the 20th anniversary of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Carole-Ann Duffy will not be quaking in her boots. Indeed, William McGonagall, were he still with us, would likely feel unthreatened. It begins:

The day we lost our Nation’s Rose,

Tears we cried like rivers flowed

The earth stood still

As we laid her to rest

A day you and I will never forget.

I’d hate to impugn the sincerity of this. Indeed, its very incompetence shows he must mean it; but what he delivers is bathos, not pathos. He seems to think that ‘rose’ and ‘flowed’ come close enough to rhyme; that we won’t notice that every line bears a tired cliché. There is an almost admirable vainglory in allowing the world to see it.

But here’s the problem: an awful lot of people thought that because it was by an international sportsman and multi-millionaire, it must be good. That the sentiment mattered more than the craft. The point of Bad Poetry Day must include in it the notion that some poetry is better than other poetry, and that some poetry must therefore be sub-standard; and that it is worth knowing what makes some poetry work (the same goes, of course, for any art form) beyond personal taste. Too many people thought Lewis Hamilton’s farrago ‘good enough’.

There is a famous anthology of Bad Poetry entitled ‘The Stuffed Owl’, compiled by Charles Lee and Wyndham Lewis. In their prolegomenon they say: “There is bad Bad verse and good Bad verse. It has been the constant preoccupation of the compilers to include in this book chiefly good Bad verse”. Accordingly, they level their sights at the likes of Wordsworth (whence the title), Keats and Byron.

Good Bad verse, they say, is innocent of faults of craftsmanship: imagine Lewis Hamilton’s effort metrically correct, rhyming well, but retaining the clichés and the bathetic imagery. All of a sudden the nexus of art and craft comes into focus. A good poem needs both.

One target of The Stuffed Owl is our own Robert Burns’ astonishing poem ‘Elegy on the Death of Sir James Hunter Blair’. Its subject matter is not dissimilar to Hamilton’s. The execution is at the other end of the spectrum. The elegy drips with overcooked misery. Here’s a taste:

The paly moon rose in the livid East,

And ‘mong the cliffs disclos’d a stately Form’

In weeds of woe, that frantic beat her breast,

And mix’d her wailings with the raving storm.-

Wild to my heart the filial pulses glow;

‘Twas CALEDONIA’S trophy’d shield I viewed;

Her form majestic droop’d in pensive woe.

The lightening of her eye in tears embu’d.-

You can tell that the man can write. His imagery may not have seemed so completely over-the-top to his 1787 audience; but the lack of restraint suggests that perhaps Burns hoped that the support he received from Blair during his lifetime might be continued by his widow. It also, perhaps, suggests that it wouldn’t be.

The tools poets use to be great exponents of their art can also be the instruments of their descent into mediocrity. Burns himself referred to the Elegy as ‘mediocre’, which demonstrates an admirable capacity for self-criticism. Bad Poetry Day seems to me a good idea so long as we use it for its stated purpose: to discover the excellent via a critical appreciation of the substandard. McGonagall doesn’t make it into The Stuffed Owl: he’s not good enough. Lewis Hamilton’s poem, I’m afraid, probably doesn’t even qualify as poetry. This may be elitist, but in all branches of Art, surely, we need to try to maintain the highest possible standards, otherwise there is a danger that the art will be devalued.

In his elegy Burns strives for art, and fails, and knows it. Many poetasters accomplish some sort of personal therapy, and that is a laudable effect of artistic endeavour. But we shouldn’t encourage them to foist their musings on innocent bystanders.

Perhaps they should be steered instead in the direction of that other celebration allotted to August 18th: Pinot Noir day.

…Her people are assembled in her bones. She’s their summation. ‘Before her time’ has almost no meaning…

(Old Highland Woman)

…Bringing its belly home, slung from a pole…

(Fetching cows)

…comma’d with corpses…

(Uncle Roderick)

…A withered hand trembles on its stalk…

(Visiting Hour)

…with amber dumb-bells in his eyes…

(Goat)

To stub an oar on a rock where none should be….on a sea tin-tacked with rain…

(Basking shark)

A few excerpts from the wonderful work of Norman MacCaig. I could go on and on…

…I am growing, as I get older…

To use words in this way! To see things as he did. Puts the reader right there – into the scene. I don’t have words for this genius. It doesn’t feel high-brow or inaccessible. I just lose myself in their beauty.

Ps. I made the mistake of viewing a tutorial on Basking Shark. It was more out of curiosity than anything else as I already loved the poem. It completely ruined it for me. Taking apart the beauty of the words, the pattern and rhythm of the flow. Awful. Poor students. Just enjoy the experience of reading or listening. Discuss and share thoughts as you read for sure – but don’t ruin the experience of poem. (So says a retired teacher! Though primary…)

Far more interestingly it’s Cultural Insurgency Day – and poets are celebrating Garcia Lorca and his work.

Tolerance (I might only like 1% of poetry I read, someone else 50%) and timeline (yesterday’s fine turn of phrase becomes tomorrow’s cliche) might also be factors. Is the technical meeting of imposed contraints comparable to the freer flow of wordplay? I knew someone who said they wrote poetry to get the poison (they didn’t actually say poison) out of their system (didn’t stop them asking for the odd evaluation though). And surely having something important to say, as @Gerry Loose comments, has to count for something? Can a translated poem still be evaluated in the same way? Randomly opening Verso’s Book of Dissent, the first poem I light upon is Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s “Freedom’s Dawn: August 1947”. Is it any good? I don’t know. I think the original was in Urdu.

Seems to me that most “poetry” is bad and barely merits the name; most of the rest (including, probably, most or all of my own efforts, even the published ones) is mediocre and unmemorable; and good, or even great, poetry is a rare and precious thing. Which is entirely natural and to be expected — 99.9999% of the books in Borges’ near-infinite Library of Babel are unreadable nonsense. Of course there’s no consensus on what’s good or great — one man’s, woman’s or generation’s “wow!” could be another’s “meh”. But you’d hope that any literate person would be able to at least tell “trash” from “maybe, just maybe”.

Yet nowadays it’s taboo to criticise for fear of offending. At any open mike night the crowd will dutifully applaud every offering, and it’s mostly impossible to tell whether this is out of actual appreciation or mere politeness. Of course it’s not up to any one person to decide what’s good and what’s terrible, but maybe we need to be a bit more willing to sort out the wheat from the chaff and call out bad poetry… and less thin-skinned when it comes to being on the receiving end. It should be OK to say, “Sorry, this just doesn’t work for me” and for no offense to be meant or taken. So, well done Dougal for raising the topic.

On haiku: I think this form is one of the most widely misunderstood in poetry. Many teachers will tell their pupils that it’s defined by counting 5-7-5 syllables; nothing could be further from the truth — even in Japanese which has a very different concept of syllables than English. For instance, the recent win of a major Japanese foreign-language haiku award by British schoolgirl Gracie Starkey with the (definitely not 5-7-5):

Freshly mown grass

clinging to my shoes

my muddled thoughts

But it’s just too easy, and suits our Western mechanical mindset, to say “haiku = 5-7-5”, and to side-step the real, crucial, but un-pin-downable question of “does the poem actually speak to you?”

Which is always the question. It’s rare but sometimes it happens and it’s always miraculous when it does. But to know that, you have to be able to tell clearly when it doesn’t.

http://abrazohouse.org/en/writing/windfall-plums/

https://87beavers.org.uk/bereaved/