Camus’ The Plague: A Tale of Our Times

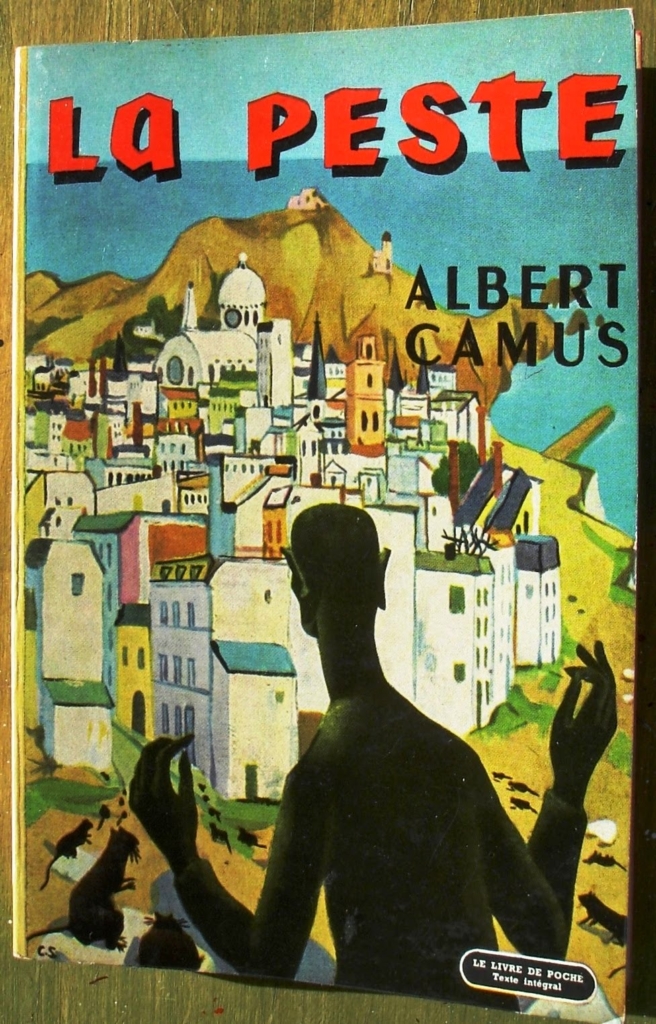

“Plagues make exiles of people in their own country.” Albert Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague, depicts a “pestilence” sweeping through the Algerian town of Oran. Camus’s Oran is grafted on to a unique landscape, right in the centre of a bare plateau, “ringed with luminous hills and above a perfectly shaped bay.” The beauty of the North African landscape is cruelly invaded by the inexplicable arrival of a diseased rat population which goes on to wreak havoc amongst its inhabitants, bringing contagion and death. The plague changes the rhythms of life in Oran, “June’s twilights” are lost in the sky, flower petals “crushed between heat and plague”, the Algerian summer is “dead and all its pleasures vetoed”. The townsfolk are initially incredulous. What human reason cannot explain, human reason does not want to accept, he tells us. “People fancied themselves free”, he writes in his habitual tone of wry cynicism.

Camus is a master of exiled narrative. With surgical precision, he extracts his characters from their peaceful isolation and forces them into a political reality, a revolutionary event, a moment naturally unfolding in the greater narrative of life. An exile himself, Camus was born in Algeria and lived through the Algerian revolt and the country’s struggle for Independence. His was a personal struggle too. He came to the end of his life at only 46 in a car accident without ever having resolved for himself the “Algerian question”, the one that marked his life and oeuvre so deep like the “hurt in my lungs”, as he writes in 1955.

By the time he wrote The Plague, Camus was already an esteemed figure within the French literary establishment. He grew up in a colony as a Frenchman with an “Algerian self-awareness” and was caught up in the overwhelming events of his time: the post-war desire to rebuild Europe and the consequent war of ideologies between the bourgeoisie and the hopeful communists –yet naïve to Stalin’s plans to quash to Hungarian revolt with blood and tanks in the streets. Violence was in the air in January 1956, when Albert Camus checked into the Hotel Saint-George. The struggle against French colonialism was escalating, with civilians becoming the primary victims. After 14 years in France, he had decided to return to try to stop his homeland from sliding deeper into war. It was a perilous mission. Ultimately, Camus the Franco-Algerian tried to find a middle way: He advocated freedom for his birthplace and a reconciliatory settlement with France. It was not to be. Two years after his death, Algeria declared her independence in July 1962 after a brutal and long war.

Camus’s novel was written at the intersection of WWII and the new dawn, the promise of a better tomorrow. Europe’s bloodied encounter with fascism made its contemporaries all too aware of Nazi genocides but also the ideological masking of its workings: fascism as “the need to deal with foreigners”, “love of the motherland”, “protecting your own”, “let’s make this country great again” and above all its diseased attachment to a charismatic ruler (usually a psychopath), its violently emotive rhetoric of confusion and lies and its strategic control of the masses to serve its dismal, monolithic entity.

Great literary works always contain a mystery of interpretation. That is why they can be read hundreds or thousands of years later and still have the same resonance. In The Plague, Camus’s rat infestation is the mirror of our perennial fear for the unseen and invincible “Other”, the unassailable force of dissent that we cannot seal off, whose imaginative air droplets precede their arrival and which we can try to downplay, “behaviourally” manage or artificially explain away but can never really control. For they will be back to remind us of the frailty of our human condition and of the need and the urgency to listen to and consider this unseen and inexplicable “Other”.

Camus’s rats work to exhibit this alterity, their claws scratching and tails thrashing in Oran’s hot and dirty streets, only to die before we can work out what is happening. The novel’s ironic observation that the rats can never be completely emptied out from the space of the text both literally and metaphorically should act as a warning for us: even when the vaccine comes, we will never be free from the virus because it represents difference itself: the condition of respecting and accepting the other’s otherness as well as our own. Our renewed commitment to listen to the earth and her worries and our preparedness to act in the face of aggressive exploitation, attack on our hard-won rights and the rights of our fellow humans, all over our shared world.

Camus was thinking about fascism of course, but like all literary greatness he is never too far from our present history. In a letter he addressed to Roland Barthes, Camus clarifies: “The Plague should be read on several levels; but nevertheless its obvious content is the struggle of the European Resistance against Nazism.” And he adds: “In a sense it is more than a chronicle of the Resistance. But it most certainly is not less.”

In Camus’s epidemiology, a plague is just as likely to produce hope as it is to spawn fascism: In today’s reality, Johnson, Cummings, Putin, Trump, India’s Modi and Brazil’s Bolsonaro test the edges of what we have come to accept as methods for governing civilised society. Commentators George Monbiot and Fintan O’Toole have joined philosophers like Judith Butler, Jason Stanley and Timothy Snyder in reinterpreting fascism for our times and extrapolating the conditions in which it becomes possible, even desirable by many. Fascist politicians promote aggressively the willingness not only to break the law and decimate its constitutional safeguards but to revel in its decimation. This is the fatal step towards the replacement of a polyvocal, well-founded democracy with authoritarian terror. Fascism’s warning signs are recognisable: the mythology of a romanticised past, the brutal distrust of doctors and scientists, the virulent anti-intellectualism, the derision towards the less able-bodied and those in forced poverty and the active violence against anyone perceived to be “foreign”, regardless of reason or consequence.

We are now facing the threat of a belligerent, loud-mouthed and cantankerous Anglo-sphere where people are burnt alive in the middle of London because “they have no common sense” or succumb to COVID because they aren’t strong enough to “take it on the chin”. Black Britons and Europeans are systematically annihilated through the stealth imposition of controlling minds and shaping narrative: psy-ops, artificial intelligence-led rhetoric and imaginary “statistics” that would put Joseph Goebbels to shame for his simplistic ways of blaming the Jews for the ills of humanity. The news that we read online are algorithmically framed, harvested and captured. Of course, the British government has form on inventing controlling mechanisms and ample time to develop them through centuries of imperial rule across the four corners of the Globe. Coronavirus has given them the space and powers to conduct their “world-beating” “super-forecasting” which is little more than a massive control operation awarded billions of pounds without proper procurement procedures and managed by Faculty and Palantir, both firms tightly controlled by the obscure figures of Dominic Cummings and Peter Thiel.

Constitutional vandalism is another well-kept weapon in fascism’s armoury. Traditionally, both the post-Weimar administrations and Mussolini in Italy have invoked the “will of the people”, both in rhetoric and in optic ritual. Stadia filled with happy, robust, vigorously fool-bloodied people, signing and flag-waving were an indispensable tool in fascist propaganda. Constitutional procedure and parliamentary scrutiny were attacked viciously under the guise of “the will of the majority”. In perfect parallel, the latest item on our contemporary agenda is control of state aid. A full-scale assault on Devolution and a blatant move to erode the powers of the Scottish Parliament is now inevitable. Without the safeguards of the European Union, devolved administrations will be amongst the first to suffer the blows of centralised rule. In Scotland, civil and political rights are protected by the Human Rights Act 1988 and provisions in the Scotland Act 1998. With the European Convention on Human Rights no longer justiciable, Scotland’s legislative competencies will be severely curtailed and all areas of administration will be encroached on by the all-powerful, and omnipresent Anglo-state in all its destructive greatness.

Is the plague upon us? It is. It always was. As Camus had imagined it, fascism is a contagion: An infectious disease, never truly eradicated from the body of society. Even when seemingly absent, it lies dormant, waiting for the right conditions to allow it to break out anew. The oppression of the Other- the Jew, the African, the European, the disabled, the Catholic, the Protestant, the Muslim- is the early warning sign of history.

And once this virus has been eradicated, like the doctor in Camus’s Plague, we must remember that “He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good . . . and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and for the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

Is this the time to moralise? No. It never is. Good measure, critical understanding and looking after each other will help us on our way out of this present “infestation”. Scotland has already demonstrated her ability by not only containing but also suppressing the virus and this is largely due to the indefatigable commitment of her public servants to put human life and well-being before any other consideration. It is perhaps a testament to our times that COVID is mirror to reflecting the differences between the nations of the British Isles by highlighting their priorities.

At any rate, Camus is not a man moralising about the moral failings of others. He recognises his own. That’s what makes him great. And there is no one better to observe, sing and create poetics in human pain than Camus himself. Let’s hear him:

Pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure; therefore we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere phantasm of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t always pass away and, from one bad dream to another, it is men who pass away […] Our townsfolk were not more to blame than others; they forgot to be modest, that was all, and thought that everything still was possible for them […] How should they have given a thought to anything like plague, which rules out any future, cancels journeys, silences the exchange of views. They fancied themselves free, and no one will ever be free so long as there are pestilences.

To the Scottish reader, Camus lends himself to a myriad wonders. Much in the same way as many of us feel in this present time, he felt himself asphyxiated; watching powerlessly, as events overtake our ability to comprehend them. His writings remain a testament to this bifurcated consciousness and monuments to teaching us that all plagues come to an end. And that, while “unable to be saints” we must always act against “terror and its relentless onslaughts”, we must “refuse to bow down to pestilences, striving our utmost to be healers.” The last three hundred years demonstrate that Scotland can withstand many challenges and, with fortitude and good will, still find her own voice amongst the family of nations.

Soon, it may be time to act again.

Interesting.

Unwelcome though it may be, here’s a bit of stupidity from my journal entry for 23rd March:

To console myself I’ve been re-reading Albert Camus’ The Plague, his extended meditation on freedom, terror, love, and exile, and on the necessity of solidarity and bearing witness to one another’s humanity in the midst of life’s hellishness.

The story runs something like this: Before the arrival of the plague, we (the citizens of Oran) were largely preoccupied with matters of commerce and finding distractions to stop us from becoming bored with ourselves. When the plague arrived, it caught us off guard; the hospitals couldn’t cope and we began to run out of coffins. With the good intention of securing our own safety and that of society generally, we imposed self-isolation on ourselves and enforced it on others. Public places were declared off-limits, streets were emptied, assemblies were criminalised.

However, our good intentions, expressed as social distancing, did as much harm as the epidemic itself. We became obsessed with cleanliness and other barriers designed to demarcate and maintain for ourselves sterile personal environments. But our social distancing began to erode our capacity to love and to experience pleasure. We fell instead into a state of terror and mutual distrust.

The Plague is often seen as an allegory for totalitarianism. It is that, but it is also an exploration of Europe’s postwar obsession with the question of how it could arise and so quickly take hold among decent civilised people. Camus’ answer is that it arises from a ‘contagion’ that’s already within us, as part of our shared human condition.

‘[E]ach of us has the plague within him; no one, no one on earth is free from it… [W]e must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him.’

The ‘plague’ in Camus’ novel is not [just] totalitarianism as such but the propensity for evil that lurks inside each and every one of us. This propensity manifests itself in times of stress when we seek to protect ourselves through social distancing from others, who are in much the same boat as ourselves, but with whom we do not ‘own’ an identity. Social distancing fosters a climate of fear and distrust, from which can be cultivated a complete subservience to the state.

The totalitarianism inherent in identity politics begins with the imperative of ‘looking after one’s own’. From the top of the slippery slope of social distancing and safeguarding, we can swiftly descend into the victimisation and scapegoating of others. Quarantining and exterminating the unclean in death camps is only the final, logical solution to the problematic of safeguarding.

I’m not suggesting we’re about to descend into an orgy of barbarity on the back of the COVID-19 pandemic. Far from it. We might be selfishly hoarding food and toilet rolls away from others, from the quite understandable fear of having to go without those things ourselves; we might be giving others a wide berth as we pass them with a scowl of distrust on our expeditions to the park (or, in my present situation, to the kitchen); but we’re still a long way from fearfully denouncing one another as sacrificial lambs to appease the authorities or conniving in a systematic cull of ‘them’, the infected, to maintain a safe environment for ‘us’, the healthy. But as things get worse before they get better, it may nevertheless be prudent to ‘keep watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment…’

‘All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences. That may sound simple to the point of childishness; I can’t judge if it’s simple, but I know it’s true.’

As Camus insists, we’ll get through this, just as we’ve survived countless other existential crises in human history. And it will not be epic deeds of heroism that gets us through it, but simple human decency and solidarity, which are the only weapons we have in our meagre arsenal.

Studied it at my (all-boys school). Loved it. Some wonderful characters. But re-reading it during lockdown, I was horrified to note that all the characters are male. One minor walk on part for Dr Rieux’ mother but apart from that half the town is completely absent. Oh dear.

Having said that one of my favourite minor characters in literature is the tragic clerk, who so much wants to write the perfect novel which wows from the first paragraph, that he has never got beyond the first sentence: hundreds of pages of different wordings of the same first sentence are the total fruit of his labours. A bit like some people’s attitude to independence and political change.

Didn’t Josef Stalin die in 1953, putting him at considerable disadvantage in planning a reaction to the Hungarian revolt in 1956? Sorry, I found that quite jarring.

I also don’t really see what part of the UK quasi-constitution we would really want to keep, at the end of the day. Cummings’ attack on the civil service may be malicious and his alternative (if such a coherent option exists) may be worse, but then again the UK civil service is a rotten keg anyway, with entrenched privilege, incompetence, corruption, racism, false dealing and world-staining malevolence. There is apparently endemic racism in the Department for International Development, the Ministry of Defence wants to weasel out of arms-sale debts to Iran and the Diplomatic Service is a world joke stuffed with privately-educated elitist bubble-heads sucking up to foreign royalty/dictators often installed by their ancestors.

I haven’t read Camus, but I guess he was writing under some strictures (censorship, possibility of death threats or something). Perhaps it is more productive to read less tortured prose these days that just spells things out more clearly. After all, fascism has ‘infected’ the Internet, and threats have moved on.

You clearly haven’t read Camus; otherwise, you wouldn’t find his prose ‘tortured’. L’Étranger was the first text I was given to read when I first went up to university to begin my apprenticeship in philosophy, and his writing novels is some of the most beautiful prose I’ve ever read, lucid and lyrical. And recognising that ‘the truth’ of the human condition is too absurd to be spelt out clearly, he’s never preachy and always ambivalent, like life itself.

Great article by Effie Samara at a time when plenty of citations of “The Plague” have been made without anybody else seeing the connection between Camus’ text and the new fascism we are seeing emerge, especially in the Anglo-American world…

I personally still haven’t been able to digest Brexit, and I doubt I ever will, having spent most of my adult life living in Europe by virtue of the various EU Treaties the UK is /was signatory too. But it’s clear to me that its root cause is the English/British superiority complex in many cases…

I believe Brexit to be the biggest mistake made by Great Britain since Munich 1938 and I fear for our European friends who now have to live at the tender mercies of the UK State instead of enjoying rights answerable in the European Courts – all the more so after the shocking treatment of the Windrush Generation by the quasi fascist British State.

The post-war Europeans and Americans who designed the new world order after the calamitous first half of the 20th century during which 100 million Europeans died, did so by building powerful transnational institutions and organizations, most notably, the United Nations, the EEC which later became the EU, and, to some extent at least, NATO among many others.

These transnational institutions and organizations provided Europe with an unparalleled era of peace and prosperity in our history. Yet today, the mere idea of transnational institutions and pooled sovereignty is derided and painted by the cynics as a concession or even a weakness.

We will all live to regret Brexit, and as Effie rightly says, we must remain alert and awake to stand up against fascism, which in Scotland means re-establishing the wide and diverse coalition of groups from Scottish Civil Society who proved so effective back in the 80’s and 90s: trade unions, women’s movement, anti-nuclear organizations, anti-racism campaigners, EU citizens, and anyone in Scotland who supports, believes and defends the sovereignty of the people of Scotland and their right to freely and peacefully choose their own democratic future, unmolested by the moronic English white nationalist project currently in power in London…

PS: We cannot and should not wait for the SNP and Nicola Sturgeon, we should be mobilizing already. And the answer is most definitely not the All Under One Banner marches. I’m sure the people behind AUOB are decent, well meaning people, but they have to understand that marching under a sea of Saltires is to play precisely into the hands of those behind the nationalist movement in England, the USA and elsewhere. To the outside world, there is no difference between a sea of Union Jacks and a sea of Saltires or (almost) any other flag. It is narrow and puts people off, people who would mobilize on a different platform such as anti-racists, anti-nuclear weapons groups, the religious leaders in Scotland and the trades unions, not to mention our EU citizens resident in Scotland. It seems to me that we need to reconstitute the broad assembly of folk from all walks and creeds of Scottish life which served us so well in the past… the message should be All Under Every Banner…

A pleasure to read, despite its message.