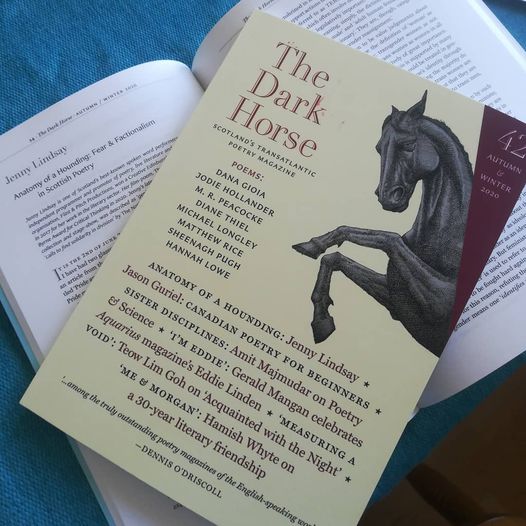

Dark Horses and Cultural Vandalism

The current issue of the excellent magazine of poetry The Dark Horse contains an essay by Jenny Lindsay detailing her harrowing experience of being ostracized and ex-communicated from the poetry and literary world of Scotland for thought crimes both obscure and imagined. The piece ‘Anatomy of a Hounding: Fear and Factionalism in Scottish Poetry‘ raises significant issues about how we manage public discourse, the perils of (anti) social media and what kind of literary and creative world we want to have. In fact, strike that, it raises questions about what kind of society we want to live in.

The whole bizarre nightmare is rich with dark irony, not least because of Lindsay’s role in nurturing talent for the last decade or so, often to the detriment of her own career (as much as poets really have careers). Lindsay was one half of the hugely successful Rally & Broad (2012 – 16) with fellow poet Rachel McCrum, and her subsequent work forming and running Flint and Pitch (from 2016), put her in the forefront of Scotland’s burgeoning poetry revival. Her debut solo show, Ire & Salt (2015), was highly acclaimed as was her 2018 solo show, ‘This Script and Other Drafts’.

When I first encountered this scene (as a non-poet and marginal writer) the overwhelming observation was that this wasn’t really about poetry at all. The hundreds of events that Lindsay and her colleagues created in clubs and bars across Scotland seemed to be characterised as places where you could be who you were, whether your ‘deviancy’ was to be queer/bi/shy/trans or even worse, a poet. The quietly seditious nature of this culture, which was carefully nurtured, should not be under-estimated.

But this was to be, I think, part of the longer term problem.

I would go as a spectator to poetry events – amazed by peoples self-honesty, fluency, confidence and the process that so many performers were clearly going through. The scene was an amazing success, it championed diversity in the best sense of a terrible word, it took real risks and it made people (anyone) feel welcome.

It was a “safe space” – and this was perhaps, in further irony, both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness. More on this later.

I had other problems with it, mostly about the risk that it was to foreground spoken-word poetry over written, and whilst the spoken-word scene has been transformed in Scotland, it has to an extent over-shadowed its older sibling. This is though, as Holden says, a “digression”.

My point is that Jenny Lindsay championed people who were vulnerable and marginalised and did this with great care and thoughtfulness over a protracted period of time. In this context, the accusations that she is either insensitive or reactionary are absurd in the extreme.

If you want to follow the whole complex nightmare, buy the magazine – but here is a quick summary.

In what will be the first and last time I link to The Spectator magazine, Nick Cohen writes: “In June 2019 she objected to a writer for the Skinny, who said they believed in ‘violent action’ against Terfs (in this instance lesbian feminists at a Pride March). Lindsay contacted the magazine on Twitter and said:

“‘Hello! One of your commentators here advocates violence against lesbian activists at Pride. I find it extraordinary that such views are given an airing in The Skinny.’

You should be able to offer support to transwomen, as Lindsay has done during her career, while deploring incitement to violence against lesbians. Although the magazine privately admitted to her it had made a mistake, Lindsay was publicly accused of transphobia.”

“On Facebook, a prominent novelist cross-examined her about her views. Fellow artists demanded that she prove her commitment to trans people. Strange language assailed her ears. Lindsay thought she had issued a polite protest about inciting violence against women, but she was told she guilty of a ‘derailment’, and her thinking was ‘colonialist’. Fake evidence was manufactured. Anonymous heresy hunters went through her poems, and found that ‘The Imagined We’ was anti-trans because it used menstruation as a metaphor. And indeed on the extreme reading, which is to say the only reading that matters, Lindsay has a phobia. She believes in showing trans women every kindness but does not think that anyone can be a woman, and that there is no material basis for being female. As she and others point out, women’s oppression becomes impossible to fight if the material reality of the female body is wished away.”

This is a difficult subject fraught by bad faith and bad actors and, frankly exploited by some people for their own ends.

Lindsay writes: “There is a very human cost to this level of scrutiny, demand for ideological purity, harassment, bullying and policing. The cumulative effects of the atmosphere I was having to try and create and present my work in … has been very difficult to deal with. The signatories include people I have mentored, booked, promoted, supported with setting up events, given free advice to, and in some cases truly and dearly loved. It is human to feel a real sense of betrayal from both individuals and a sector that has largely turned away from addressing the this issue with the gravity and reasoned logic it deserves. The silence of many former friends too is difficult to compute. I have defended strangers against less.”

This is difficult.

I personally, and in this journal generally, have tried to steer a path of being a defender and ally of trans-rights whilst simultaneously showing solidarity to women and to give space for feminist voices on these pages. I think still that’s possible, though its clearly challenging, particularly as it’s difficult to have open dialogue (something Lindsay repeatedly calls for).

There’s two other aspects to this that make things more difficult. The first is that a lot of this happens in the margins, in the DMs, in the nooks and crannies of a literary world that is too often a ghetto. It’s not in the public view and that’s where it can and does get nasty. People using anonymity to hurl abuse at people they don’t know is disgraceful but commonplace. The second is that there is a view that much of this has now obscured bigger issues like endemic poverty, squalor, class and inequality. “We now talk of pronouns instead of talking about changing society” this argument goes. I have some sympathy for this view but I don’t agree that issues about power exclude or obscure issues about class. Defending people who are marginalised or threatened does not, in my view undermine class politics but is part of a continuum about exploitation and its resistance. Dividing people who are marginalised or persecuted only strengthens the patriarchy and capitalism. We are – and need desperately to be – stronger together. Let’s find common cause.

There’s lots of contradictions here. The “safe space” that Lindsay created did not create the sort of rigorous dangerous creativity she has championed. In fact it created a closed space, a space where many of her current detractors festered. Too much was/is ‘performative’ ie. ‘done for the performance of’ rather than ‘done for the thing itself’. Too much was/is about the individual rather than about the world.

Lindsay closes warning: “What happened to me could easily happen to any of you if we allow lies to become truth and women to be policed by standards we would never demand of men.”

“We cannot have a healthy literary culture if we allow this to continue, and without our institutions supporting values of free, democratic, creative expression … the alternative is cultural vandalism.”

I still live in hope we can navigate through this nightmare together, with kindness, generosity and solidarity. We might need to learn new ways of creating dialogue. Great credit is due to the Dark Horse for publishing this and giving Jenny Lindsay the space she deserves and has spent so long creating for others.