1990 A Year of Change and No Change

2020 has been a momentous year. Brexit, Black Lives Matter, Coronavirus all seem to have changed the world more than any year in recent memory. In this article I look back at 30 years ago, 1990, a truly remarkable year when the world did change dramatically.

Make no mistake, 1990 was some year, across the planet. For a start, in 1990 you would not be reading this, as the internet didn’t exist. Tim Berners-Lee had proposed what he called The World Wide Web in 1989, its first incarnation, at CERN, would appear later that year, with Berners-Lee launching the world’s first web page on December 20th 1990. How we consumed information and communicated was entirely different. The world’s first portable digital camera was produced that year and, although there were mobile phones, there was no text messaging service.

In Europe the political map was changing swiftly. At that time the EU (then called the EEC) had only 12 member states. The Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact, communist regimes in Yugoslavia and across Eastern Europe collapsed, leading to the re-unification of Germany in October and the creation of new independent states across Europe.

In South Africa President FW De Clerk announced the end of the ban on the African National Congress (ANC) and Nelson Mandela was released from prison. It was the end of apartheid and the beginning of the process that would lead to the first free election for voters of all races just 4 years later.

In the Middle East Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait, an event that would lead to the first gulf war in 1991, a nightmarish quagmire that is still playing out to this day.

In Britain, the Poll tax was introduced in England, one year after Scotland was used a Guinea pig for its introduction. That led to riots that would eventually bring down Prime Minister and Tory leader Maggie Thatcher, replaced by John Major in November. Two months earlier a certain Alex Salmond had been elected leader of the SNP for the first time. Nicola Sturgeon was still a teenager, studying law at Glasgow University.

It was the year that Roald Dahl died and JK Rowling began writing a book about a boy wizard that would take her five years to complete.

And, against this background of turmoil and change, Glasgow was declared “European Capital of Culture”.

According to Glasgow City Council “Glasgow City Council saw 1990 as part of a strategic investment programme, which would ensure the long-term future of the cultural sector and contribute greatly to economic and social regeneration.” The events, spread across venues throughout the year, with a focus on “THE BIG DAY” a huge event featuring the cream of Scottish pop music at the time and some international guests. This idea that Glasgow would be reinvented, through celebration of the City’s culture and investment from private developers, is still one being pushed to this day by successive council regimes. Indeed in the years running up to the event the District Council as it was known at the time, had successfully employed marketing techniques to set out to persuade locals and visitors that Glasgow was changing. Articles appeared in newspapers here and across the world proclaiming this “change”. Bill Bryson among the many prominent writers who apparently waking up to Glasgow as a centre of culture, while the money-men were eyeing the city centre’s “potential”.

Glasgow Action was designed to improve Glasgow’s ‘entrepreneurial spirit’. Its Chairman, Sir Norman Macfarlane, was head of the Clydesdale Bank. Other members included bankers and industrialists as well as the Council Leader, Jean McFadden.

The centre-piece of the year would be the unveiling of the new Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, 15 years in the planning, the city of culture status would be the catalyst that would bring what cynics called “Lally’s Palais” (a nod to the former Provost Pat Lally) to a reality.

There were many critics, not just of the design of the venue itself but of the whole concept of regeneration. Glasgow had lost two thirds of its industrial jobs in recent years, a substantial chunk of council housing had been lost through the “right to buy” scheme, and unemployment was high. Against the background of rising activism and community organising in opposition to the the Poll Tax, Workers City was formed, to provide a counter-cultural response.

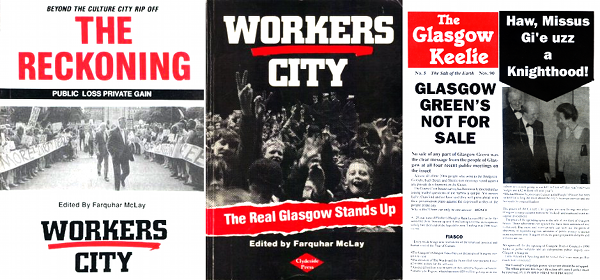

Workers City featured a range of artists and critics working in literature, theatre, music and poetry. They produced the books Workers City (1988) and, in 1990, The Reckoning: Private Loss Public Gain, as well as a newspaper The Glasgow Keelie with 20 issues over 3 years. In Farquhar McLay’s Introduction to Workers City, he writes:

“GLASGOW: European City of Culture 1990. The announcement came from the Tory Arts minister, Edward Luce, in October 1986. It had a sickeningly hollow ring to it. Looking at the social, cultural and economic deprivation in working-class areas of Glasgow, and thinking about the rigours of the new Social Fund and Poll Tax to come, it sounded like blatant and cynical mockery […] There is widespread acceptance that it has nothing whatever to do with the working-or the workless-class poor of Glasgow but everything to do with big business and money: to pull in investment for inner-city developments which, in the obsessive drive to make the centre of the city attractive to tourists, can only work to the further disadvantage of the people in the poverty ghettoes on the outskirts”

But Workers City had limited success and legacy in the face of the massive corporate investment.

The aformentioned Council and Government sponsored The Big Day was the main feature of the Year of Culture to sugar the controversial redevelopment plans. The cream of Scotland’s popular talent from Hue and Cry to Sheena Easton would appear at a vast public concert with side events across the city. Away from the main event the highlight, for me was the temporary development of the Clyde bandstand, once a focus of Glasgow punk scene for a gig with Billy Bragg, Michael Stipe, Natalie Merchant, Eddi Reader and Dick Gaughan among others.

The bandstand is one example of nothing coming from the years big plans, the site was abandoned after that day, now a gap in the shape of an auditorium forgotten in the many promises to redevelop the water side.

But the clash between mainstream and alternative cultures, arguments about music venues missed the bigger picture.

Chik Collins, Social science researcher, formerly of University of the West of Scotland, and now Rector of the University of the Faroe Islands, was part of the team that linked The Year of culture to Glasgow’s “forced decline” and that forced decline to Glasgow’s excess mortality

“The defining feature for Glasgow from the early 1960s for the next 4 decades is its forced decline, at the hands of the Scottish Office in Edinburgh – industrially and in terms of population. From the early 1980s, city centre regeneration, based on property development, retail, leisure and tourism, was supported by the Scottish Office, and embraced by the Council, as a ‘permitted’ alternative path of development – though never as one that could begin to address the overwhelming needs of the city. But even then, the city leadership had to fight huge hostility from Edinburgh to its attempt to be the European City of Culture in 1990. The subsequent opposition from within Glasgow to that, including from the Workers’ City group, largely failed, with one or two exceptions, to grasp what was really happening, and to direct its ire at the institutional forces which had driven, and were continuing to drive, the great damage being done to the city and many of its citizens. Rather than being focused on Edinburgh and the Scottish Office, the controversy tended to take the form of a local conflict within the City between the ‘boosterists’ and the ‘workerists’ – each accusing the other of betraying the needs and interests of ordinary Glaswegians, while the much more serious perpetrators were elsewhere.”

Since 1990 much of the cityscape has changed, the remaining council housing stock was transferred to Housing Associations, Glasgow’s council-owned culture and leisure sector was hived off into the arms-length Glasgow Life. There is now less democratic accountability and control of these aspects of the City than at any time since before the setting up of the “corporation” and City Councils as we know them.

The legacy, in terms of buildings, is probably best represented by Glasgow’s Royal Concert Hall’s steps. These days, its origins have been largely forgotten and they became a place to protest during 2014’s referendum campaign and since. Back then it was jokingly called “Lally’s Palais” a derogatory term indicating it is an ego project for the former Provost Pat Lally. When plans to redevelop the north end of Buchanan Street came to light three years ago a “Save Our Steps” campaign emerged. At a demo for Palestine at that time I bumped into the poet Tom Leonard who was very much part of the Workers City mindset in 1990. We laughed at the idea of Glasgow’s radicals now campaigning to save a place they would have gladly demolished 30 years before.

To me, that was the last time I met Tom and represents to me a reflection on how so much has changed while Glasgow really hasn’t.

Of course 1990 was also a momentous year for music in the UK in general, the year that indie bands discovered ecstasy and the great tribes of the 70s and 80s merged into one Youth Culture at Spike Island. I have compiled a playlist to accompany this piece. It opens with Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet, still relevant today but most of it echoes the opening lines of the next tracks. Despite all of the turmoil and change many will remember 1990 as a year where they just wanted to get loaded or the year when they were going to dance, and have some fun.

Jim Monaghan writes that the Workers City group was formed to provide a ‘counter cultural response’.

This was its weakness. It failed to provide a political response which garnered popular support.

The view that Edinburgh and/or the Scottish Office was responsible for Glasgow’s decline is entirely unconvincing.

As mentioned, “Since 1990 much of the cityscape has changed”. The number of high buildings around and creeping towards the city centre could destroy the scale of the city and the view of sky and skyline which is still there in the city centre – which most are only subliminally aware of but which is important. The height of developments is due to the pure greed of developers to maximise profit with no concern about the effect on the environment or on people. If building volume is required, including affordable housing, the huge number of wasteland sites should be subject to Land Value Tax to stop developers sitting on them until the planners give in and let them build what they want and higher. Even more effective would be compulsory sales with purchasers having to commit to complying with the planning stipulations set by the authorities. The same should apply to buildings left to become derelict by developers for the same reasons. I hope such action is taken before Glasgow just becomes another mess of characterless, impersonal high rise developments.

Aye,

Rule Number One in any “Regeneration” scheme is: Somebody* Needs To Get Rich.

Until that condition is met, nothing can be built, nothing can happen.

* Preferably the same “body” that got rich last time. And the time before that, and the time before that…