Infodemic – an Epistemological Problem

Fake news

Fake news

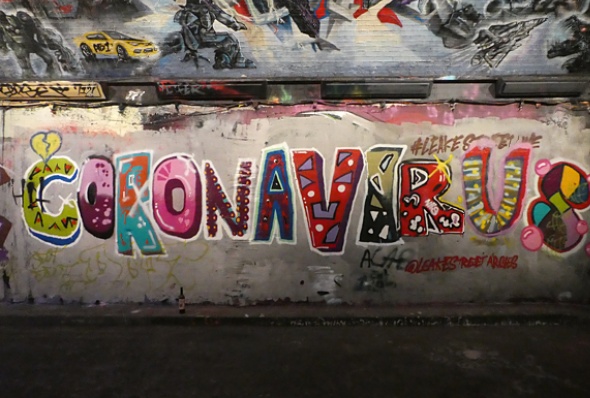

Few places in the world have been spared the novel coronavirus, much less the onslaught of misleading information surrounding the disease. This little-understood virus, which has forced governments to shut down normal life in order to control its spread to sustainable levels, has inevitably led people to seek answers.

Enter conspiracy theories and alternative media stories, which have gained in popularity and helped to fuel protests against government restrictions and the flouting of public health guidance, like mask-wearing, intended to protect the population. Conspiracy theories have appeal in times of uncertainty: they give believers a clear black-and-white narrative and, importantly, someone to blame.

The problem is that fake news can lead people to behave in inappropriate and even dangerous ways. It’s also a problem that, as experience has shown, can’t be solved by policing without raising concerns about freedom of expression or censorship.

An Infodemic

Ironically, the relatively vibrant news media landscape makes the spread of misinformation (rumour) and disinformation (intentionally false information) more likely.

The landscape is also changing quickly. Information manipulators are always one step ahead of information regulators. Online platforms themselves are a moving target for regulators, as users regularly change their consumption habits. Although Facebook remains the world’s most popular social networking site, the most widely used is now the messaging service WhatsApp, whose closed discussions enable ‘problematic content’ to escape wider scrutiny and spread quickly through its so-called ‘echo chambers’.

It’s long been clear that the problem of ‘fake news’ is practically unsolvable. This is because our information behaviour has changed. We’re subject to what the World Health Organisation has dubbed an ‘infodemic’; an over-abundance of information that makes it hard, if not impossible, for people to find trustworthy sources.

Global distrust

Mis/disinformation has also been a problem for the mainstream media, as they struggle with shifts to digital news consumption and plummeting advertising revenues. Against these trends, the so-called ‘legacy media’ of print and television journalism has launched a propaganda campaign aimed at separating its outlets from the bad apples.

Despite this campaign, however, trust in legacy media remains just above the global average for all media, according to the Reuters Institute.

Yet social media platforms especially, despite being vectors of misleading content, have been rather complacent in response to it. One UK study has found that such platforms fail to remove 95% of mis/disinformation reported to them.

The unprecedented COVID crisis has forced the hand of social media companies’ to some extent. Some have made pledges, including to ban false information, and removed or placed warnings on other misleading posts, Donald Trump’s included.

But much more mis/disinformation continues to circulate, threatening our democratic institutions and public health alike.

So, what’s to be done?

We can’t and, perhaps, shouldn’t rely on commercial companies and/or the state to moderate our content. Moderation can quickly become manipulation. Moving forward into a future in which the overabundance of information is only going to grow ever greater, we need to assume greater responsibility for our own consumption. We need to become more critical in our thinking, cultivating our own ability to check alleged facts and to analyse and evaluate arguments.

We must all become philosophers, in other words, and sceptics to boot, assuming disbelief as our default mode, trusting nobody, and challenging those who’d lay claim to our belief to convince us out of our intransigence.

We must simply learn to be much less gullible.

I suspect that many of us already are questioners and less gullible than the average punter (or at least we _think_ we are). Trouble is, my vote counts just the same as any other easily-led individual. And therein lies the main problem.

“Trouble is, my vote counts just the same as any other easily-led individual.”

I don’t see the equality of our electoral system as a problem. It has the virtue of ensuring that we all have the same amount of spending power in the political marketplace and that the various ideological brands have to compete for our custom.

The trouble is that we’re rubbish consumers: our choices are too often constrained by brand-loyalty, and we’re too often susceptible to the manipulations of marketing psychology.

In other words: a) we don’t shop around enough, and b) we tend to buy on impulse rather than on calculation.

A bizarre evasion of the main reason why people don’t trust government, state, academic or corporate media: the tendency of these organizations lie, keep silent and propagandize to suit their own agendas. More than that, the age-old entrenchment of hypocrisy and cant in British culture leads to the expectation that lying and evasion is the mark of the social elite. Look at all the recent uncoverings of suppressed histories of slavery resulting from the Black Lives Matter pressure, leading to British banks making somewhat belated apologies.

Some people argue that ‘oh, all that stuff was known about’ but that is simply another lie. As my old political science lecturer told us, there are many British wrongdoings that are widely known to researchers in their fields, that never get into popular discourse, curricula, or cultural products. Many wrongdoings have been successfully repressed by a secrecy-obsessed royalist state.

Philosophy is not about ‘learning to be less gullible’, whatever that can mean, it’s about asking increasingly better questions. Although the Herman–Chomsky Propaganda Model as explained in their book Manufacturing Consent is often recommended, I found Medialens’ Why Are We the Good Guys? to be an easier read, and of course it starts with a question:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Why_Are_We_the_Good_Guys%3F

“…the main reason why people don’t trust government, state, academic or corporate media [=] the tendency of these organizations lie, keep silent and propagandize to suit their own agendas…”

That’s almost what I said: the main reason why people SHOULDN’T trust them = their tendency to lie, keep silent, and propogandise in order to further their own agendas. Which is also the main reason why people should rather assume an attitude of scepticism towards their claims.

PS Isn’t this what Chomsky et al are saying?

PPS Shouldn’t David Cromwell and his cohort be telling us why they’re the good guys?

Or, more to the point, shouldn’t we, in the spirit of scepticism, be asking why sceptics like Chomsky and Cromwell are the good guys?

@Anndrais mac Chaluim why bring ad hominem fallacies into the argument? Who said Chomsky and Cromwell were good guys? Is there anything that makes you think their form of dissent is not genuine criticism and an attempt to make the world a better place, according to their published views?

Just in case there is any misunderstanding, the authors of Why are *We* the Good Guys?: Reclaiming Your Mind from the Delusions of Propaganda are not claiming to be good guys, they are referring to the default position (or unspoken assumption) of Western state-corporate media. They are challenging the constant position that, “for all its admitted faults and shortcomings, ‘the West’ is necessarily a force for good in the world.”

If readers would prefer more up-to-date examples, they have a later book out called Propaganda Blitz. While on rare occasion they may slightly overstate some of their criticism based on the evidence presented, I think their arguments and analyses stack up pretty well. Their strength is that they tend to cover the omissions, and sometimes it is difficult for the public to ask questions about topics that are missing from public discourse (or intentionally kept impenetrable, like the British quasi-constitution). For example, they will use comparative analyses of mentions across media databases to show double standards in coverage.

@Anndrais mac Chaluim, however, since our understanding of the world is necessarily mediated (that is, we have to rely on others for information), solutions must be collective (involve those others), most obviously along the lines of glasnost (openness/transparency) and perestroika (political, economic and social restructuring); and not dependent on individual (heroic) transformation. We are still in the early days of social media, and its potential for underpinning collective intelligence is as yet under-explored.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_intelligence

As long as all nodes in the collective are of the same type, they may be relatively interchangeable. Humans may be individually irreplaceable, but collectively replaceable, as one generation follows the next. A particular kind of problem arises when some nodes are of a different type, for example profit-seeking planetary-irrealist corporations, who may usurp some human privileges, and are increasingly given AI-powered voices. Of course, since non-human lifeforms are also generally excluded from communication collectives, the voices of animals, plants and ecosystems are also excluded from political debate, and therefore their truths are effectively silenced.

It’s their ‘attempt to make the world a better place, according to their published views’ that sets them up as ‘good guys’ and the publication of their views that makes those views subject to critical evaluation.

And, yes, ‘reality’ (our understanding of the world) is indeed what William James called ‘a joint-stock company’. For me, it’s axiomatic that man is a self-creative being; we develop the capacities peculiar to our species as we live and work in community with others and, in the process, generate our understanding of the world and of ourselves.

For thinkers like Habermas (another one of my ‘good guys’), this self-creative process depends on our communicative competence, and our communicative competence is disrupted whenever unequal power structures dominate our media. That’s why it’s a key strategy of scepticism to ‘disrupt the disruptors’ by pursuing a negative dialectics of immanent critique.

You want a society with everyone ‘assuming disbelief as our default mode, trusting nobody, and challenging those who’d lay a claim to our belief to convince us.’

I can see why you want a different society to the one we have. My concern would be that the cure could be worse than the disease. Michael Sandel in his recent book, ‘The Tyranny of Meritocracy’ argues in favour of the common good and communitarianism. I think that the emphasis on distrust which you advocate would make such a society even harder to build than it is at present.

I’m not so fussed about society; society will take care of itself and will be no better or worse than we (hell mend us!) collectively deserve. I’m saying only that, when it comes to the information we consume, we need to take personal responsibility for what we swallow and be less trusting and more discerning in our consumption.

I’ve no idea what an association of autonomous, free-thinking people would make of itself. Something Rawlsian, perhaps?

I could live with that.

‘society will take care of itself’

Or not, as the case may be. You do not have to look far to see societies which are making a poor fist of taking care of themselves. The autonomous free-thinking people might just come up with something Hobbesian rather than Rawlesian. Throughout history, the former has been much more common than the latter.

Asking us to become philosophers strikes me as utopian and utopian ideas in politics have a habit of ending badly.

That’s precisely the point. An association of autonomous, freethinking people might make anything it wants of itself.

And is it really all that ‘utopian’ to urge people to think critically rather than swallow indiscriminately?

It is utopian to suggest that people should become philosophers – in any real sense of the word. I think that, at present, far fewer people swallow indiscriminately than you believe.

My problem is that too many people are attached to the material status quo.

I self-identify as a philosopher, having studied the craft formally for seven years and continued to practise it since. Are you saying I’ve been misidentifying myself for all that time by using the term in a bogus sense?

And I’m sorry to hear you’re upset by the fact that ‘too many people are attached to the material status quo’. But what business is it of yours what other people are attached to?

Laissez faire, s’il vous plaît!

Anndrais mac Chaluim

I have no problem with you being a philosopher. My problem is your statement that ‘we must all become philosophers’. It strikes me as totally unrealistic.

If people are – as I suggest, wedded to the material status quo – building a better society is nearly impossible because they they are unwilling to make sacrifices such as

paying more in taxation, which would be necessary for a fairer society.

Well, it’s hard to see how a society, in which bodies are so satisfied with their material condition that they’re unwilling to change it, could, from their point of view, be bettered.

I’m sorry you think that my call for each of us to cultivate one’s own ability to check alleged facts and to analyse and evaluate arguments – that is, to do philosophy, this being what philosophers essentially do – is unrealistic. There truly is no hope for us, then.

You refer to a society in which bodies are ‘so satisfied with their material condition that they are unwilling to change it.’

I would say that it is more a case of people fearing a deterioration in their material condition – as might happen if there were large tax increases. Alex Salmond asked for a ‘penny for Scotland’ and got turned down by the voters.

As the material condition of very many in Scottish society has improved in the last 40 years, the percentage of the population fearful of a loss of this material improvement has increased.

You need only think in terms of more foreign holidays, bigger homes, more motor cars and electronic goods to realize that the status quo is probably more attractive materially than it has ever been.

Yes, you’re right there. Folk are largely content with the status quo and don’t want to risk their wealth as consumers by changing it. Better a bird in the hand…

Nothing wrong with that.

Is the last sentence a quotation by Marie Antoinette ?

Je ne comprends pas…