The Other Side of Sorrow

THE OTHER SIDE OF SORROW: From The Province Of The Cat. George Gunn on Space Command and land ownership, offshore energy and offshore banking.

Through me the way into the suffering city,

Through me the way to the eternal pain,

Through me the way that runs among the lost.

Justice urged on my high artificer;

My maker was divine authority,

The highest wisdom, and the primal love.

Before me nothing but eternal things

Were made, and I endure eternally.

Abandon every hope, who enter here.

(Canto 3, Dante’s Inferno, Translated by Alan Mandelbaum)

The four long lorries carrying the four huge white steel casings crept along Martha Terrace and River Street. The low yellow Winter light was perforated by the flashing blue lights of the lorries themselves and the several police cars escorting the component column parts for the new windfarm on the Causewaymire. Wick had come to a standstill. The service bus to Thurso, which I was waiting to board on Bridge Street, like everything else, had to wait. The everyday business of the Caithness capital took second place to this latest manifestation of onshore renewable energy. “Ah, well,” the rational mind said, “at least it’s not nuclear.”

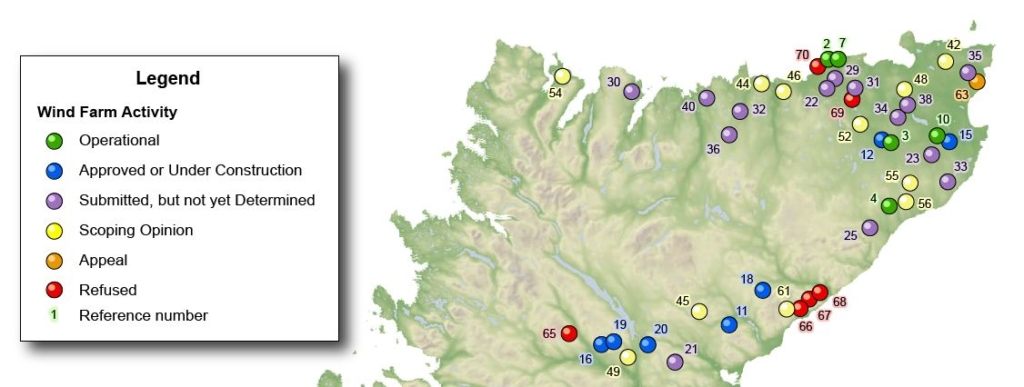

The current 21 turbine strong wind farm operated by Ventient energy on land owned by a private individual has, literally, expanding neighbours. Construction News recently published the figure of 94 wind farm projects UK wide “in the pipeline” i.e. not under construction, and without planning permission yet. Of these, 19 are in Caithness. That is 20% of the nation’s windfarms “in the pipeline” in Caithness. That is disproportionately large on a local scale. Caithness already is covered in windfarms. There are over twenty the last time I counted, plus the massive offshore array near the Beatrice oil field off our east coast. Everywhere you look, from whatever location, the turbines stand erect like so many steel Triffids. Verticals out of the horizontal. Why this should be is not because Caithness is a raised plateau on the far north east corner of the Scottish Highlands with a good wind resource, but rather that there are plenty of landowners willing to lease the land to the likes of Ventient, npower, SSE and others and make easy profits as a result.

Caithness has a resilient and hardworking farming community but they are being undermined, like everyone else, by a small minority of slipper farmers who prefer easy rent to growing food. As a locality with an historically chequered relationship with the nuclear industry it seems we are to be the site of the new energy bonanza that, like the free electricity promised by Dounreay in the 1950’s, will bypass the local people who as usual are not consulted and will not reap any benefit. Since the 1990’s, when onshore wind was first established in Caithness, the price of electricity has increased steadily every year. The more energy that is exported from Caithness, both from onshore and offshore, the steeper the bill for the domestic consumer. Renewable energy, which should benefit all and the planet, as it is presently constituted, benefits only a few.

The essential economic relationship at the heart of this windfarm dog-dance is that between the landlord and the power company. By virtue of the 1989 Electricity Act and its legislative progeny, planning decisions for windfarm developments over 50 Mw are made by the Scottish Government, which makes no secret of its appetite for windfarms. The Scottish Government has the facility of granting or not granting planning permission for each individual turbine project. The people, ironically have no power. A further irony is that the need for renewable energy has never been higher in Caithness, as it is in every part of Scotland. Meanwhile the tidal stream project south of Stroma in the Pentland Firth struggles from lack of investment. Energy policy, of course, is reserved by Westminster.

There is nothing wrong with wind power as part of our renewable energy mix. What is wrong with wind farms, as they are currently operated, is almost everything else. The construction takes place abroad. Other than installation and basic maintenance the usual local jobs-glut forecast disappears like snow off a dyke. The reality is that the actual wealth flows south and the artificial poverty comes north. But it doesn’t stop there. The A9 brings you into Caithness but as far as corruption is concerned it might as well lead you into Canto 3 of Dante’s Inferno and The Gates of Hell.

“Through me the way into the suffering city,

Through me the way to the eternal pain,

Through me the way that runs among the lost.”

From the brilliant Ferret Productions we learned last week a few interesting and salient things about Ventient Energy. One is that they operate 13 wind farms in Scotland. The company is headquartered in Edinburgh. Yet it is a subsidiary of a company, Ventient Energy Holdco/Sarl, which is registered in Luxembourg. That company itself is part of the IIF International Holding group which is registered in the Cayman Islands and is advised by JP Morgan Investment Management. Ventient reported that its revenues for 2019 were £152 million with an “operating profit” of £26 million. J P Morgan has global assets of £2.4 trillion. Being owned in the Cayman Islands means that private equity investors and companies escape tax.

Wind energy is being used by charlatan companies in a secondary market of buying and selling which cheats the Scottish people of any financial or social benefit gained from their natural assets. We have been here before with North Sea oil in the 1970’s and 80’s. As far as hydro-carbons are concerned the asset stripping will be ongoing until the wells are dry. Then we will be left to clean up the mess. The Scottish Government could easily clean up the contemporary mess of wind farms in Scotland through the setting up a publicly owned energy company. But don’t hold your breath. In 2019 when he opened Ventient’s new headquarter in Blenheim Place in Edinburgh the Scottish Government energy minister, Paul Wheelhouse, described the company’s expansion as “a vote of confidence in the future of onshore energy in Scotland.” Meanwhile money is stripped out of companies, tax authorities take a hit but hedge funds make a killing.

We live in a world of financial mirrors and alternative reality. International capitalism which wraps itself like a snake around the world does not reflect the real word. Instead it is rather like a portal into a world of anti-matter and anti-reality where everything is the opposite of what it claims to be. Which leads us to the current Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak. There is the small matter of the official register of ministers’ interests and the £430 million he forgot to mention. Admittedly the multi-million-pound portfolio of shareholdings and directorships are in his wife, Akshata Murty’s name, but you know, he might have thought it prudent (shock horror, even honest) to declare it. You might also think that the Westminster authorities would be asking the Chancellor some hard questions but alas, no. According to The Guardian (28th November)

“A Treasury spokesperson said the prime minister’s independent adviser on ministerial interests ‘confirmed he is completely satisfied with the chancellor’s propriety of arrangements and that he has followed the ministerial code to the letter in his declaration of interests’”

So we go further into The Inferno.

“Justice urged on my high artificer;

My maker was divine authority,

The highest wisdom, and the primal love.”

The Prime Minister, the “high artificer” in chief, Boris Johnson is completely satisfied and, of course, in Westminster he has “divine authority”, as Dominic Cummings found out. They look after their own and we watch and wonder.

We may also wonder why it is that the Prime Minister, nine months into a viral pandemic in which almost 1.5 million people have died world-wide, thinks that this is a good time to announce a raft of funding packages for the Ministry of Defence of between £16 and £25 million, for a “National Cyber Force” and an “Artificial Intelligence Agency”. This will, according to that deeply drawn well of intellectual water, The Sun, “make Scotland and the whole of the UK better protected and able to play a more active role defending out allies and values.” You will no doubt be delighted to learn that “we” will have a “Space Command” at RAF High Wycombe. The Sun drooled on about all this, hardly able to contain itself,

“Successful rocket launches will give Space Command a sovereign capability to put weapons and surveillance satellites into orbit to defend British interests, without relaying on other nations.”

By “British interests” I wonder if they mean Ventient’s tax dodging “interests” in The Cayman or the Chancellor’s wife’s undeclared millions? The “public interest” in Bojo-land is a less hallowed verity than “British interests”. “Public” are ours. “British” is his.

As Dante’s hero reads on The Gates of Hell,

Before me nothing but eternal things

Were made, and I endure eternally.

Abandon every hope, who enter here.

Yet “interests” are malleable and whilst in the north of Scotland they are often comical you could not say they are divine. The rockets Space Commander Johnson wants to blast off into space to defend us will no doubt be launched from the proposed Space Hub Sutherland on The Moine peninsula on the north coast? Or maybe it will be from Scolpaig on North Uist? Or maybe, just maybe, from the Shetland Space Centre on the old RAF base at Saxa Vord on Unst? The Moine project has been the recipient of £17.3 million of public money including £9.8 million from Highlands and Islands Enterprise. The two main service providers and project partners in this are Orbex, who will make and launch the rockets and the US company Lockheed Martin, the biggest arms manufacturer in the world, who will provide the satellites. Lockheed Martin received £23.5 million from the UK Space Agency. Last year Lockheed Martin had total assets of valued at $44.87.

But the North Sutherland Space Hub is now thrown into doubt as Lockheed Martin have switched allegiance to the Shetland Space Centre on Unst. Also the Danish landowner Anders Povlsen is against it. Povlsen, who is worth some £4.5 billion, owns 12 Highland estates, several of them in Sutherland, one next door to The Moine. This sort of thing he could never do in his native Denmark. The “something rotten” Shakespeare raised in Hamlet has switched from Denmark to Scotland. The billionaires’ company Wildland Ltd has sought a judicial review of Highland Council’s planning approval raising concerns about Space Hub Sutherland’s impact on the Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Protection Area, and has sought a judicial review of Highland Council’s permission for the satellite launch project. However, another of the Povlsen’s companies, Wildland Ventures Ltd, has invested £1.5 million in the Shetland Space Centre.

At least, as he stood approaching the Gates of Hell Dante’s hero had the poet Virgil for a guide. As I stood, waiting for my bus that was stuck on Wick’s Bridge Street, gazing at the four, slow moving, wind turbine casings which had recently been off-loaded at Wick harbour, an unsettling feeling of powerlessness came upon me. Unlike Dante I had no guide. I was an individual waiting on a bus and other than the loose and gentle bardic-skaldic mantle of my people I hold no public office, nor do I aspire to. Then I remembered that the very first poetry reading I ever did in my life was here in Wick when I was a teenager, way back in the 1970’s. It was in the old Mercury Motor Inn and was organised by the late great county librarian and poetry engine, David Morrison. I had to read before no less than Somhairle MacGill-Eain or Sorley Maclean as he is more widely known. Ignorant as I was then of this great poets work and language I have made an attempt to educate myself since. That day changed my life. Suddenly, looking at this metal, lorry-loaded procession, the ending of his towering poem of 1939, The Cuillen, came into my mind,

Beyond the lochs of the blood of the children of men,

beyond the frailty of plain and the labour of the mountain,

beyond hardship, wrong, tyranny, distress,

beyond misery, despair, hatred, treachery,

beyond guilt and defilement; watchful,

heroic, the Cuillin is seen

rising on the other side of sorrow.

(An Cuilithionn, Somhairle MacGill-Eain)

Civilised life is like a spider’s web. Easy to destroy. But hard to construct. All of the above – and for laying it out I beg your forgiveness – is just a set of instances and examples of why Scotland needs to be an independent country. Once we become one, in order to rid ourselves of and to protect ourselves from such corruption, we need a revolution.

©George Gunn 2020

Damn right

Thank you so much for this piece. Beautiful poem and perfect set beside the darkness of the energy guys. No apologies necessary.

Thanks again George. Your Northern posts are welcomed, enjoyed, and read with respect. They are informative and authoritative. Strategic even, hopefully influencing the course of events.

Perhaps predictably, I post below the Gaelic original of your Somhairle MacGill-Eain quote. The English translation you give is no doubt his own, but of course his actual poetry is in the original Gaelic. I am long of the opinion that poetry as such cannot really be translated, only transposed. This is especially true of MacLean’s poetry. These Gaelic words must be read with great emphasis on momentum and vowel musicality – with particular weight on the final word of each line. It is poetry to be spoken and heard. Chanted almost rap-like, indeed. But studiously measured and with portentous gravitas. It hails from 1939.

Thar lochan fala clann nan daoine,

thar breòiteachd blàir is strì an aonaich,

thar bochdainn, caithimh, fiabhrais, àmhghair,

thar anacothruim, eucoir, ainneirt, ànraidh,

thar truaighe, eu-dòchais, gamhlais, cuilbheirt,

thar ciont is truaillidheachd, gu furachair,

gu treunmhor chithear an Cuilithionn

’s e ’g èirigh air taobh eile duilghe.

No doubt the poem is best kept as a precious secret, closely guarded by the Gaelic. Its purity would only be profaned by foreign ears.

Is cinnteach gu bheil thu ri fealla-dhà. You’re joking of course.

He’s a wind-up merchant. A well-read one without doubt. But still, a wind-up merchant.

No, I’m just wondering (seriously) what motivation and value there could possibly be for locking the poem away in Gaelic. There’s a genuine hermeneutical problem buried here that might be worth excavating and looking at.

Indeed there IS a “genuine hermeneutical problem” in accessing certain kinds of poetry such as MacLean’s. That problem seems ultimately insuperable. What is done is done as far as Sorley’s work is concerned. However, in future all poetry should be written in English only and not “locked away” in another language. What other remedy could there possibly be?

I don’t think there is a remedy to the problem of non-translatability, Fearghas; I don’t think Somhairle could have written his poetry in English. In fact, the problem is such that I don’t think even Gaelic readers can ‘get’ Somhairle’s poetry; only Somhairle could – and he’s deid.

Is poetry something that can be communicated, regardless of the language it’s written in, is what I’m wondering? Is its true meaning decidable by anyone other than Somhairle himself, and perhaps not even him? Is the undecidability of an artwork’s true meaning not at least part of its sublimity, the fact that it effectively says nothing?

The final line of my doctoral thesis on Interpretation, Decidability, and Meaning back in 1986 was: ‘When I listen to Somhairle reading his poetry, I listen in utter incomprehension, but simply in awe. As both Nietzsche and Dylan [Thomas] said: perhaps it is not the destiny of a poet to be understood.’

Sorry, to make that clearer: ‘Is the true meaning of Somhairle’s poetry decidable by anyone other than Somhairle himself…’

Can any audience be anything more than a bob of clapping seals?

(I get the “applauding seals” allusion, thanks.)

OK Anndrais, some excellent questions, not so easy to pursue with short remarks.

The “locked away” (or “locked in”) idea of course gets stretched by extreme postmodernism to encompass all writing and indeed all speech. This ultimately encloses each of us in our own forlornly inaccessible subjective bubble. The fact that you are engaging on Bella Caledonia is evidence in itself you don’t go that far, of course. But the dismal influence of any reductionist “locked in” view on society is that injustice-resolution through verbal negotiation gets seen as a fool’s enterprise. Skepticism gets further fuelled through malign manipulation of data by Media and Courts. The collapse of etiquettes of civilized discourse leaves society with brute power as the only recourse. The ongoing self-empowerment of the State to police people’s vocabulary is a hugely alarming step in that dark direction. Once the State usurps the power over our words it also alone gets to decide what is officially “true”. I needn’t labour the obvious reference.

However, you yourself are focussing merely on aesthetic communication (primarily poetry as a verbal medium, but nodding towards art in general). For example you ask:

“Is the undecidability of an artwork’s true meaning not at least part of its sublimity, the fact that it effectively says nothing?”

There is an apparent self-refutation in that formulation as it stands. Personally finding the meaning of an artwork “undecidable” conflicts with the simultaneous assertion that “it says nothing”. There is also perhaps the impeding bias that meaning must yield itself exhaustively to words. The unviability of that premise is obvious in painting, dance, instrumental music etc. But for poetry, being words already, the trip-wire is more subtle. Yes poetry is words, but the words as such are hopefully martialled and transcended in an aesthetic manner. If the aesthetic element is clunky then it fails as poetry. We are left with IKEA instructions.

To return to the “locked away” phrase you used, you commented:

“I don’t think even Gaelic readers can ‘get’ Somhairle’s poetry”.

So OK, that alerts us to the germ of truth in the ultra-postmodernist pitch. We do often find it challenging, frustrating even, to entirely understand one another even in everyday conversation. How much more so in epiphanous language-stretching poetry. But we can still generously listen to each other, begin to pick up the nuances, get to know the other person. Existence is far deeper than words. Simply put, we begin the journey of learning the other person’s language in order to “meet” them as authentically as we can.

Which peroration allows me to air the following Wikipedia excerpt (since edited out, I think) on the subject of “INDEXICALITY”:

An episode of the Simpsons plays off the popular character Smokey Bear, whose motto is: “Only YOU can prevent forest fires”.

Robot Smokey Bear asks Bart: Only WHO can prevent forest fires?

(Bart has the choice between the buttons “ME” and “YOU” so he presses “YOU”.)

Robot Smokey Bear: “You pressed YOU referring to ME. That is incorrect. The correct answer is YOU.”

Yes, solipsism does have some alarming implications. That doesn’t invalidate it as a theory, of course, but I believe it’s on a hiding to nothing for reasons other than it might have logical consequences we don’t like. It behoves us as rational beings to always follow the argument whence it leads.

I also believe that the ‘undecidability thesis’ doesn’t commit us to anything like solipsism. It just asserts that a ‘true’ reading of Somhairle’s poetry is undecidable, which leaves us rather with a plurality of provisional readings than none at all, each of which number can be deepened through dialogue with others.

In this scheme of things, each reading of Somhairle’s poetry is a translation of its text that can be carried into the next reading, which can, in turn, be carried into the next and the next and the next, in a series of translations that will never exhaust its meaning in a final ‘true’ translation. The process can never be exhausted because at no point can we ever tell whether a concordance has been reached between a translation and the original text because we can never have access to the original text, only to a reading of it. The most we can strive for is a concordance of readings/translations.

If you like, the text of ‘An Cuilithionn’ is, in its reading, a Gaelic translation of Somhairle’s poem; the text of ‘The Cuillin’ is, in its reading, an English translation if Somhairle’s poem. Outside its reading the poem doesn’t exist; it’s meaning consists in the innumerable plurality of its actual readings, none of which can be ‘truer’ than any other, its Gaelic translation no ‘truer’ than its English one.

Counter-intuitive perhaps, but intuition is the metaphysics of savages. What the poem – any poem – ‘really’ means is an enduring mystery indeed. Which is why Somhairle’s poem can never be exhausted or imprisoned in any language. It is what both he himself and Auld Grieve would have called a piece of ‘world literature’.

I can take what you say up to your penultimate paragraph, which for me succumbs to po-mo subjectivism, a gnostic-like disjunction between psyche and physicality:

“If you like, the text of ‘An Cuilithionn’ is, in its reading, a Gaelic translation of Somhairle’s poem; the text of ‘The Cuillin’ is, in its reading, an English translation of Somhairle’s poem. Outside its reading the poem doesn’t exist; it’s meaning consists in the innumerable plurality of its actual readings, none of which can be ‘truer’ than any other, its Gaelic translation no ‘truer’ than its English one.”

Nor do I accept for a moment your disparagement of intuition in the opening sentence of your final paragraph (which no doubt is why I find that penultimate paragraph problematic):

“Counter-intuitive perhaps, but intuition is the metaphysics of savages.”

To call Sorley’s original Gaelic text (“in its reading”) a “translation”, and not only that but a translation “no truer than its English one” is to stretch the epistemological elastic too far. To assert that “Outside its reading the poem doesn’t exist” depreciates the abiding objective reality of its concrete inscription in symbols whose meaning remain communally comprehensible and verifiable in everyday experience. And I suggest that the “common” person “intuitively” knows when a line is being crossed. Sure Sorley’s poetry or a Beethoven symphony can be lifted off the page and interpreted differently in performance, but even then a core constancy is presupposed. ‘An Cuilithionn’ is a poem in Gaelic. The poem’s core meaning is inscribed in the enduring though weather-beaten stone of that language. An English translation is an objectively different entity, however closely related. A Bach fugue for organ can be transposed to guitar. But Bach nevertheless had the pipe organ in mind when he wrote it. And the sheet music can lie around gathering dust or blow off the piano when someone opens the window.

Anyway, enough of that. Here follows Sorley’s own retrospective reflections on his poem, in a passage quoted in the book whose cover is illustrated in George’s article above:

WORDS OF SORLEY MACLEAN (1999)—

“It was in the Spring or early Summer of 1939 that I started what was meant to be a very long poem radiating from Skye and the West Highlands to the whole of Europe. I was regretting my rash leaving of Skye in 1937 because Mull in 1938 had made me obsessed with the Clearances. I was obsessed also with the approach of war, or worse, with the idea of the conquest of the whole of Europe by Nazi-Fascism without a war in which Britain would not be immediately involved but which would ultimately make Britain a Fascist state. Munich in September 1938 and the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia and Franco’s victory in Spain in early 1939 convinced me that the only hope of Europe was the Red Army of Russia, and I believed that all the anti-Soviet propaganda, or most of it, came from Fascist or pro-Fascist sources. The first two parts of the poem were made by 1939, when I was closest to Communism, although I never accepted the whole of Marxist philosophy, as I could never resolve the idealist-materialist argument. I regarded philosophical materialists as generally more idealistic morally than philosophical idealists. The poem stopped abruptly with the conclusion of the second part in late May or June 1939 and was not resumed until late October or November 1939. It was abruptly stopped some time in December 1939, but the concluding lyric came to me in sleep in the last days of December 1939, or at least the ‘Cò seo’ verses did. When I was invalided out of the army in 1943 there was talk of publishing it, but W. D. MacColl’s objections to almost every line of my own translations of it delayed that until the behaviour of the Russian Government to the Polish insurrection in 1944 made me politically as well as aesthetically disgusted with most of it. I reprint here what I think tolerable of it.”

(‘AN CUILITHIONN —1939— THE CUILLIN 1939 & UNPUBLISHED POEMS, Somhairle MacGill-Eain Sorley MacLean’ edited by Christopher Whyte, The Association for Scottish Literary Studies, Glasgow 2011)

And as to translations, my brother just mentioned to me that while watching a ‘Cyrano de Bergerac’ movie in French he noticed the English subtitles offering : “My nose goes ahead of me by 15 minutes.”

Interesting… My words here are intended as a po-mo deconstruction of the traditional dichotomy of ‘mind’ and ‘matter’. But your reading stands.

Thanks for Somhairle’s retrospective interpretation of his poem. That reading will certainly be carried with everything else into my next translation of his words.

Anndrais, Many thanks for honouring me with such an excellent mental workout. My deeper brain will duly retain and digest your fine analysis. The cud will be chewed.

I am about halfway through Máire Ní Annracháin’s 1992 high-level study of Sorley’s oeuvre:

‘AISLING agus TÓIR: An Slánú i bhFilíocht Shomhairle MhicGill-Eain’

(An Sagart, Maigh Nuad, 1992) —

“Is iad an struchtúrachas agus an tsicanailís is mó a bheas faoi chaibidil agam chuige sin.”

(“I will generally be looking to structuralism and psychoanalysis in my procedure.”)

She has this lovely observation on page 129:

“Ní hé an Cuilithionn, ach an croí, an ceann scríbe.”

(“Not the Cuillin, but the heart, is the destination.”)

It is indeed deeper and deeper into the heart of our own conversations that Somhairle’s with An Cuilithionn leads us.

Slàinte!

Thanks Fearghas. Yes, it is his own translation.

Thank you George for the great writing, as always.

Thank you Fearghas and Anndrais for the thoughts.

Thank you Bella for being the host.

Food for thought and thought for food. Sorley, Raasay, and the rest.

Outstanding essay, analysis, useful information . Tweeted to the lucky people I could tag.

And yes, revolution to ensure your new nation does not become simply a smaller container of die alte Scheiss.

George, you forgot to mention the ammount of subsidy paid to the landowners,(in proportion to the number of turbines?)

I had a conversation with an accountant a few years ago who told me of a Caithness crofter/client who had the huge problem of receiving 75,000 pounds a year for the next 25 years (and not having a clue what to do with it) and I think this was just for 2 turbines,

Sorry not to mention Sorley Maclean,

However going South one summer our family stopped at the Old Mill coffee shop in Blair Atholl, as we had our coffee and cake a busload of Italian Tousists swepped in bought some tea towels and other objects of Scottish culture which they were obviously seeking and swept out knocking over an old man’s coffee in the process. I bought a coffee and took it to him, “have this coffee Mr Maclean”.

Scotland’s most famous living poet akin to Burns bulldozed by cuture vultures.