The Deaths, Legacies, & Emergence of Sporting Icons

“Maradona was more than just a great footballer. [He] was a special compensation factor for a country that in a few years lived several military dictatorships and social frustrations of all kinds” – Jorge Valdano (2014)

In the days following the death of former professional Argentinian football player Diego Armando Maradona – who passed away on Wednesday 25th November 2020 at his home in Tigre, aged sixty – few could contest the truly global reach held by this icon of ‘the beautiful game’. Proclaimed a sporting legend in his own time, Diego was adored and revered, loathed and detested, and yet, in his peak remains, for millions, the greatest player ever to have graced the field. As tributes poured in from around the globe, a new generation – one, on the whole, more digitally apt – have been exposed to many of his greatest moments for the first time. From the ‘Hand of God’ to his ‘Goal of the Century’ (moments that happened merely four minutes apart), his leadership for club and country; his international and domestic successes; and his deft talent on the ball; much has also been made of his cocaine addiction and financial crises. Undoubtedly, many aspects of Maradona’s life were lived out in the media headlines.

Though, as former international teammate Ossie Ardiles advised, ‘[e]verybody wanted to be with him, everybody wanted a piece of him, so [his adolescence] was incredibly difficult’, Diego commanded the love of supporters wherever he plied his trade. His former team Società Sportiva Calcio Napoli (S. S. Napoli) with whom he won the club’s only two Serie A titles (in 1987 and 1990) and the U.E.F.A. Cup in 1989, even appear set to rename their stadium the San Paolo-Diego Armando Maradona Stadium (presently named the San Paolo Stadium) in Diego’s honour. Truly, Maradona’s reach was global in a way few of his contemporaries could match.

Some of you may be asking what Maradona’s death has to do with Scotland?

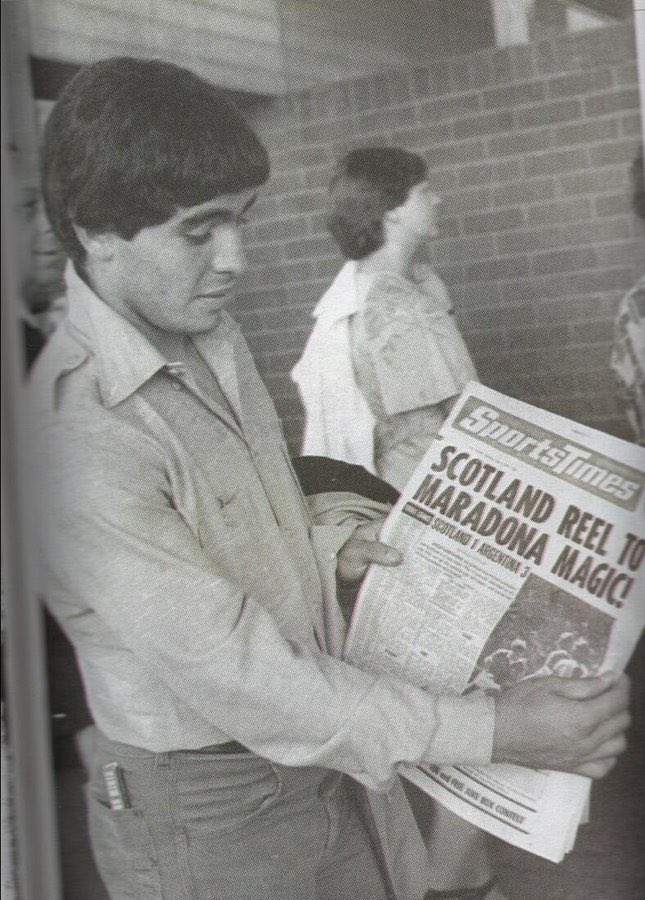

There’s plenty of football fans (and plenty ethnic nationalists or Anglophobes) who cherish the lad for ‘getting one over England’ at the Estadio Azteca in Mexico ‘96 when he out jumped Peter Shilton; whilst there may be a handful of readers fortunate to have witnessed Diego’s first international goals as the Argentines left Hampden with a 3-1 win in 1979. Those in attendance would have seen Maradona sporting a Scotland shirt post-match after swapping tops with Scotland’s goal scorer Arthur Graham (then of Leeds United). Almost thirty years later, in November 2008, in his first game as national coach, Argentina once again triumphed over our men’s team. There’s even been chat about members of the Tartan Army turning the Scotland versus England game at Wembley Stadium (London) during the 2020 men’s European Championship (read Euro 2021…) group game into ‘Diego Day’ in jest, donning Maradona face masks in recognition of the aforementioned ‘Hand of God’. Elsewhere we’ve heard some more turmetuous efforts to connect El Diego to Scotland with commentary from Archie MacPherson suggesting:

“In many ways he was a typical ball dribbler in the style of the typical Scottish inside forward. So there was an element of Scottishness in the way he played. You dream that all sorts of players will emerge again. You’d love to see another Jinky or Jim Baxter. But I don’t think there will ever be another Maradona.”

Regarding connections at club level, there were rumours the Argentine star ordered a Dundee F.C. shirt to his then-home in Cuba after his friend and former strike partner Claudio Caniggia signed on at Dens Park for the 2000/01 season. The club would later confirm that “there was written correspondence between Diego Maradona, his representatives[,] and Dundee Football Club which outline both parties’ desire for Diego Maradona to play in a one-off glamour friendly for Dundee [against S. S. Napoli]” – a match that would have earned him a quarter million payday. Some years later, in 2013, one of his match-worn Napoli shirts was displayed in the Scottish Football Museum alongside those of Puskás, Pelé, and Zidane. A handful of murals have even sprung up such as a Hand of God-inspired piece in Blackhill (Glasgow) and on Dundee’s Arbroath Road. Thus, whether during international matches or the impact the mere rumour of his turning out at Dens Park had on the city of Dundee, Maradona touched the lives of many – football fans and socialists alike – and that includes folk in Scotland.

Entertain & Education: Society in Microcosm

Many of us can trace our interest in, or adoration of, association football back to a particular moment. For me, it’s the men’s 2004 European Championships (Euro 2004). Just turned eleven years old, Dutch-Surinamese midfielder Edgar Davids captivated me from his first touch against Germany in the opening Group D match (a one-all draw). With his tight dreads and distinctive dark goggles, Davids’ flair and no-nonsense gameplay captured my mind, and I felt a compulsion in my body to replicate every touch, every turn, every pass. Desperately in need of a player of similar stature and role, I quickly fell for Bolton Wanderers’ Nigerian footballing magician Jay-Jay Okocha; whilst my eyes rarely left Charlie Miller at my own club, Dundee United, following his career over in Norway, Belgium, and Australia. Others came and dominated – Barry Robson, Hidetoshi Nakata, Jason Scotland, Stelios Giannakopoulos, and, for the briefest of moments, Karim Kerkar – but a love for the game was cemented in the summer of 2004. These days it’s more about Erin Cuthburt, Johnny Russell, Dimitri Payet, Arturo Vidal, Alex Morgan, and Hayley Lauder.

As I grew, and became more conscious of race, language, dirty money, and eventually my own queerness, my interest in the game shifted from merely the on-field performances and the gossip surrounding off-field transfer dealings, to how social issues manifested within the stadia. It’s something I’ve written about for Left Ungagged (see Almost Anyone But Malky; and ‘We’re Not That Kind Of Club’: Football, Fascism, And THAT Banner), whilst my own community development practice took me to Show Racism the Red Card Scotland, resulted in an undergraduate thesis reflecting on the capacity of football to serve as a medium for education, and led to a range of academic papers co-authored alongside my friend and former manager at the Red Card, Nicola Hay (now Dr. Hay following her work alongside Roma children in schools throughout the U.K.).

In the latter Ungagged article, amidst voicing my frustrations and anger at what I’d witnessed from fans at my own club – “Fucking Jessie!” for pulling out of a leg-breaking and [potentially] career threatening challenge… (Scottish Cup Replay against Hibs); “Bloody poofter!” when the full-back fails to clear their lines… (Play-off Second-leg against St. Mirren); and a slew of anti-Traveller and other racist comments that don’t bear repeating’ – I sought to emphasise just how political football truly is:

“Every time a current or ex- football player, manager, bureaucrat, or supporter group comment publicly on ‘political issues’, fans take to Facebook, Twitter, or the like to mask their dissent or objection to the message or issue with comments akin to ‘keep politics out of football’. If we ignore the racist or homophobic chants heard week-in-week-out in stadiums the world over, immigration and work permit issues, ‘dark’ or oil money flooding clubs boasting a global appeal, awarding international competitions to states with horrendous records of human rights abuses, bananas being thrown on the pitch, sexist comments from fans and commentators alike, Islamophobia, national anthems blasting before international fixtures, banning women from attending live matches, the stereotypical descriptions of strong black players as ‘a beast’, military or police teams fielded in domestic leagues, constant hyper-sexualisation and objectification of many of the world most talented female athletes. suicides and poor mental health due to sustained abuse, pricing working class fans out of ‘their’ stadiums, independence campaigns, fascist salutes from players, and left or right wing supporter associations, then perhaps they’re correct?”

Football is so much more than entertainment, and the death of the man I believe to have been the greatest professional player in the history of the game, has prompted me to consider the impact and legacies of those afforded the privilege and platform that comes from their status as globally-recognised elite level athletes. This, therefore, is my commemoration of Diego, a meditation on the words and actions of a generation’s new ‘idol’, Marcus Rashford, and a reminder of the ongoing frustrations many female players endure with the enormous investment and wealth disparity between gendered leagues. Though there are countless other examples to be considered and many clubs like FC Sankt Pauli (St Pauli) with unapologetically antifascist ethos, Boca Juniors, Esport Clube Bahia, or Olympique de Marseille who deserve column spaces, this contribution wishes to focus on the legacies of individuals within the game, the purpose of which will become clear.

Politics & Platform

“You don’t need to go to university to know that the United States wants to wipe Syria out of existence”.

Even as a player, Maradona spoke publicly of his left wing political stance, voicing his frustrations with U.S. imperialism, advocated an independent free state of Palestine whilst condemning Israeli offensives as ‘shameful’, backed Brazil’s Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva as well as Bolivia’s Evo Morales, and made public appearances alongside his friend Fidel Castro whose image he immortalised in a tattoo on his left leg. A 1987 meeting in the Vatican with Pope John Paul II led to public condemnation of the church’s concentration of wealth, with Diego later recounting to the press, ‘I argued with him because I was [stood] in the Vatican and I saw all these golden ceilings and afterwards I heard the Pope say the Church was worried about the welfare of poor kids. Sell your ceiling then amigo, do something!’ Yet, for all his talent on the pitch and his political leanings off it, Diego’s legacy is a deeply complicated one.

“I am from the left in the sense that I am […] for the progress of my country, to improve the li[ves] of poor people, so that we all have peace and freedom. We cannot be bought, we are lefties on the feet, we are lefties on the hands, and we are lefties on the mind. That has to be known by the people, that we say the truth, that we want equality, and that we don’t want the Yankee flag planted on us.”

In 2007, he appeared on Venezuela’s then-President Hugo Chavez’s evening talk show, proclaiming to viewers that ‘everything Fidel does, everything Chavez does for me is the best’; whilst in 2005 he has proclaimed to a 4,000 strong U.S. counter-demonstration in Argentina that he was ‘proud as an Argentine to repudiate the presence of this human trash, George Bush’. Yet his socialist beliefs and support for people’s movements throughout Latin America extended beyond comradeship and utilising his public profile, for at the turn of the millennium, Maradona commenced a four year residency in Cuba during which he credited the state healthcare system, particularly La Pedrera Clinic, for his recovery from addiction – the same world leading healthcare system that had doctors flown in to Italy as international aid during the early months of the global pandemic. At the time, Maradona stated that Castro ‘opened Cuba’s doors to me when clinics in Argentina were slamming them shut because they didn’t want the death of Maradona on their hands’. The legacy and success of his time spent recovering in Havana meant that following surgery in early November 2020, Diego’s family had hoped he could be transferred there once again.

In his online B.B.C. Sports column the day after Maradona’s death, Spanish journalist Guillem Balague offers one of the more comprehensive descriptions of Diego, stating that:

“[a]s much as I thought I knew Maradona, I realised once I began to research my book on him that I knew virtually nothing. [T]he reason for that is because there were 100 different Maradonas. The magician, the cheat, the god, the flawed genius, the loving father, the serially unfaithful husband, the generous benefactor, the foul-mouthed oaf, the boy from the barrio with magic in his boots and the man who made it to the top of the mountain and fell down it, his body broken by cocaine.”

Yet, even with this challenging and somewhat problematic personal life, the societal impact of Maradona is impossible to deny. The current Manchester City F.C. manager, Pep Guardiola, recently spoke of a banner he witnessed in Argentina translating as ‘[n]o matter what you have done with your life, Diego, it matters what you do for our lives’. As such, when the historian Norberto Ferrera is being quoted stating that ‘Maradona’s connections to Latin American leaders were more affectionate than strategic’, it becomes clear – whether through the shrines to him at the clubs he played for or his friendships with\ socialist leaders across his home continent – that as flawed or loved as he was, for many, El Diego’s very public life was symbolic. ‘We’re all in Diego’s debt for all the happiness he gave us’, some stated following his death, whilst the love was clearly reciprocated – as evidenced through Maradona’s public statement when he returned to Argentina on what would become his final trip:

“I am eternally grateful to the people. Every day they surprise me, what I experienced in this return to Argentine football I will never forget. I was out for a long time and sometimes one wonders if people will still love me, if they will continue to feel the same.”

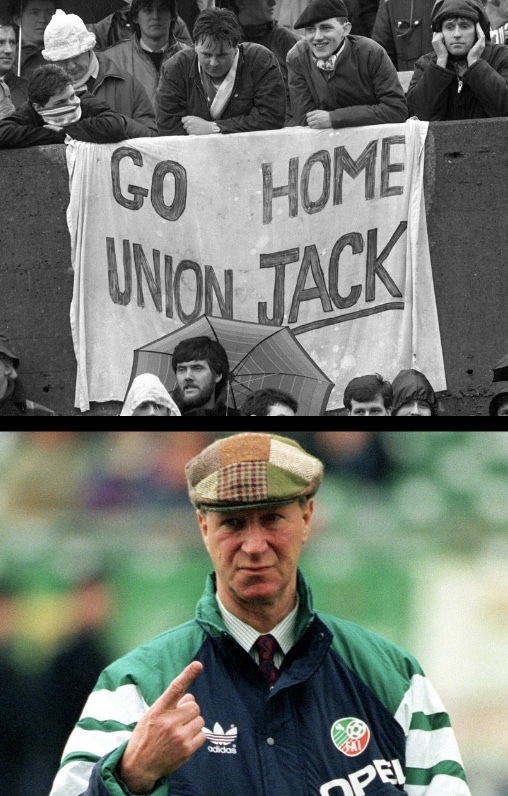

Reported in The Independent, a S.S. Napoli fan said of Diego, ‘[h]e gave voice to the people who could not speak, a feeling of satisfaction to the marginalised. He made the poor feel rich. There was no social difference when Napoli was playing. We were all one’, and whilst their lives occurred in very different contexts, it’s an untimely coincidence that Englishman John ‘Jack’ Charlton – 1966 F.I.F.A. World Cup winner, record appearance holder for Leeds United F.C., and Republic of Ireland manager between 1986-1996 – passed away just four months prior to El Diego. The subject of the newly released documentary from Gabriel Clarke and Pete Thomas, Finding Jack Charlton (2020) considers the manager’s impact on the Irish people, with the film offering ‘personal perspectives, along with previously unseen archive, [providing] an intimate window into Jack’s charismatic personality, his managerial philosophy’ before ultimately ‘detail[ing] Jack’s previously undocumented life with dementia’. Though Charlton lived well into his eighties, the aforementioned production rapidly altered in its premise, instead centring the struggle Ireland’s greatest ever football manager endured as his dementia took over. In the trailer alone, the hurt and emotion engulfs the viewer as Jack’s partner asks, ‘they think a lot of you over in Ireland, don’t they?’, only to be met with a response of ‘I’ve no idea’.

Charlton was without many of the nationalistic hostilities of those living in Ireland and in Britain. His understanding of the impact the war and exploitation of the Irish people was well documented. When pressured by journalists on why he was willing to call-up British-born players to the national team, Charlton’s response raised the social and economic impact of the war, stating that ‘every player we brought into the squad considered himself Irish’, stressing that ‘[h]ad it not been for the economic circumstances which forced their parents or grandparents to emigrate, they would have been born and reared in Ireland’. It’s a quote which, if placed in a different context, could not be far off Bill Shankly’s publicly stated socialist understandings. As such, the legacies these lads from Northumberland and Esquina created clearly touched many people beyond those they ever met, and, unfortunately, in Charlton’s case a people he struggles to remember.

As with Charlton’s legacy, other footballers have achieved significant feats. In 2005, Ivory Coast striker Didier Drogba was credited with helping end a four-year civil war. Recalling the moments following the nation’s World Cup Qualifier victory over Sudan, Carl Anka advised that ‘[w]ith the nation in the midst of a civil war, torn by religious and political tensions, Drogba seized a unifying moment for his country and invited TV cameras into the Elephants’ changing room where he made a speech to camera’.

“Men and women of the Ivory Coast! From the north, south, centre, and west. We proved today that all Ivorians can co-exist and play together with a shared aim: to qualify for the World Cup. Forgive! Forgive! Forgive! The one country in Africa with so many riches must not descend into war. Please lay down your weapons. Hold elections. All will be better.”

As the figurehead of his national team – a squad containing players of diverse nationalities, religions, and political philosophies – Drogba’s speech played a significant part in facilitating a ceasefire. The speech led to the proclamation that ‘[s]ome players win trophies. Others inspire people. It is not hyperbole to say Didier Drogba did both and helped to end a civil war’. When individual elite level matches attract millions of viewers; and when World Cup finals can attract an estimated three billion viewers across a tournament, few people command the level of recognition or audiences of these professional athletes. There have been suggestions that warring nations drawn together for competitive international games have, in the case of a 1998 game between the U.S. and Iranian men’s teams achieved ‘more in 90 minutes than the politicians did in 20 years’. Several other examples will be explored below.

No Gods, No Masters

Whilst Maradona’s iconic status extends beyond football – though there are plenty for whom that’s all he was or needed to be – Diego remained a ‘working class hero’ for many who grew up in poverty; an example of who they could be and a man who embodied the party lifestyle his talents afforded him (often indulging far too excessively), yet, it’s also true that, as a person, he was deeply flawed. His conduct off the field drew the headlines and there’s no denying that his behaviours – some of which Balague described above – hurt a great many people. Folk like Diego and Jack were legends, indeed, heroes for many, in their own days. Today, however, we’re living through an ever more rapid digital revolution (notably even within the game through, for example, V.A.R.) . Once many sporting icons were out of reach for most of us, the equivalent to the movie stars with whom they shared our T.V. screens, yet social media (primarily Twitter) now allows direct access to the people occupying the same societal positions. Afforded a unique and unprecedented platform, the capacity for sway and influence – for better or worse – is immediate; and, as such, we should consider the lives and legacies of those who are more tangible today than ever before. At the time of writing, arguably the most prominent example of Marcus Rashford, a twenty-three year old English striker with Manchester United F.C.

Though it’s been suggested that ‘many footballers were keeping a social media presence purely because it was the done thing’, arguing that this creates ‘[s]omewhere with a captive audience for them to promote themselves and any products they might want to flog’, Rashford – who has since been awarded (and accepted) an M.B.E. – built on his previous activism of co-running the In the Box campaign which saw more than 1,200 packages of essentials delivered to those residing in homeless shelters, by partnering with FareShare to provide estimated four million meals to children across England where no replacement scheme was in place for when the schools closed. Informed by his own lived experience growing up in Wythenshawe, Rashford described his motivates to take action during the lockdown in an interview with the B.B.C.:

“In the past I have done a lot of work in regards to children and when I heard about the school’s shutting down, I knew that meant free meals for some kids that they are not getting at school. I remember when I was at school I was on free meals and my mum wouldn’t get home until around six o’clock so my next meal would have been about eight o’clock. I was fortunate, and there are kids in much more difficult situations that don’t get their meals at homes.”

Despite thousands of activists, many charities, and politicians working to address food and childhood financial poverty, it took Rashford’s intervention and the subsequent rally of support to pressure Boris Johnson’s government to reserve their decision to end the free meals initiative. When establishing the Child Food Poverty Task Force, Rashford was able to bring together many of the U.K.’s largest supermarkets, producers, and delivery companies to directly address government failings. Together, the committee produced a three-part manifesto demanding:

- ‘Expanding free school meals to every child from a household on Universal Credit or equivalent, reaching an additional 1.5m children aged seven to 16’;

- ‘Expanding an existing school holiday food and activities programme to support all children on free school meals in all areas of England. instead of the current 50,000 children that are helped’;

- ‘Increasing the value of the Healthy Start vouchers – which help parents with children under the age of four and pregnant women buy some basic foods – from £3.10 to £4.25 per week, and expanding it to all those on Universal Credit or equivalent, reaching an additional 290,000 people’.

Though opinions on many elements of the game remain open to debate, that many football players and teams create legacies that have the capacity to bring about significant societal change is not. In Italy, Associazione Sportiva Roma (A.S. Roma) have partnered with the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children, U.K. charity Missing Kids, Italian group Telefono Azzurro and National Center for Missing Exploited Children over in the U.S. for their Missing Children initiative. The programme which sees all signing announcements paired with information about a missing child in one of the partner countries in a Twitter post. Several missing children have already been found, in part, as a result of the mass exposure the posts garner. Indeed, Sky Sports reported that ‘Roma’s numerous Twitter accounts cater for over 15 different languages and their overall presence on the site amounts to around three million followers’. The approach was inspired by the success of Minnesotan alternative band Soul Asylum’s 1993 release ‘Runaway Train’, the video for which centred on the same concept.

“When they see a football club posting a video of their missing child in front of millions of people it gives them hope that people are still looking for them. To have seven young people reunited and home safely is incredible, and I think there can be more in the future. I think there is traction on social media from all fans, not just those of Roma, they understand the role that they can play by simply retweeting. Then it increases the awareness of people on their timeline and then they might recognise someone”. – Paul Rogers. (A.S. Roma Chief Strategy Officer)

One of today’s most celebrated players, Portuguese international forward Cristiano Ronaldo, has similarly dedicated himself to many projects – one of the highlights being the circa €1.5million he raised for those living in the Gaza Strip of Palestine when he auctioned off his 2012 Golden Boot trophy. Others fortunate enough to play at the most elite and monied levels of the sport have made similar financial contributions either where they’re from or where they play; Mesut Ozil, for example, donated his full earnings from the Deutscher Fußball-Bund (the German Football Association) following the 2014 F.I.F.A. World Cup in Brazil to local children’s charities supporting young people with medical costs associated with treatments and surgeries. A significant issue to note on the capacity of elite athletes to support community and socially-oriented projects is the sustained financial and wealth disparity between overall investment in men’s football over women’s. To quote Norwegian striker Ada Hegerberg – winner of the inaugural Ballon d’Or Féminin, twice B.B.C. Women’s Footballer of the Year, and the 2016 U.E.F.A. Best Women’s Player award – in considering the impact of Covid-19 on modern women’s football, she states ‘[w]e’re kind of at the stage where we’re still in need of that help and when you see football as a whole and the men’s football is struggling you can also imagine yourself how the women’s football is affected’. Hegerberg remains amongst those working to improve pay conditions for women’s players and given women’s football is still so often part-time (with players often navigating multiple professionals), the financial disparity means that, on the whole, male athletes are far more capable of utilising their wealth for community initiatives. It’s also worth remembering the misogynistic commentary Martin Solveig- the host D.J. on the night of the first Ballon d’Or Féminin award – subjected Hegerberg to, asking her to twerk as she arrived on stage.

In addition to the fantastic impact icons like Maradona or Cristiano Ronaldo have been able to have internationally, as well as the many players who’ve joined Spain’s Juan Mata in his Common Goal programme whereby professional athletes donate 1% of their salary to charity, many players have taken action in their immediate localities. Such examples include that during his time with Sunderland F.C, Jermaine Defoe’s close relationship with Bradley Lowery during his struggle with neuroblastoma. Following the Grenfell Tower Fire (London) in June 2017, then-Arsenal defender Hector Bellerin promised to donate £50 for each minute he played during that summer’s men’s Under-21 European Championship in Poland. With his team enjoying a successful run through to the final, he committed £19,050 to the British Red Cross. Others such as Scotland international Lisa Evans have created training centres in their name. The Lisa Evans Soccer Centre, for example, run by Forfar Farmington F.C. are able to share in her legacy as someone who came from the East of Scotland; whilst the club can celebrate Evans by displaying one of her shirts from her time with Fußball-Club Bayern München Frauen. Another such centre has been launched by Dundee United Community Trust to create opportunities for young girls in the Dundee area.

[T]oday is the birth of the Maradona myth’

Returning to Marcus Rashford, going forward, he has promise to utilise his profile to support communities in the face of ‘a lack of empathy’, proclaiming ‘[t]o all MPs: This was never about me and you, this was never about politics, this was a cry out for help from vulnerable parents all over the country and I simply provided the platform for their voices to be heard.’ Even whilst the likes of Tory M.P. David Simmonds (representing Ruislip, Northwood, and Pinner) can position themselves as the very embodiment of the ‘lack of empathy’ Rashford earlier condemned, by suggesting Labour’s provision of free school meals during the players youth meant they could ‘curry[…] favour with wealth and power and celebrity status’; or fellow Conservative M.P. Brendan Clarke-Smith (Bassetlaw) proclaiming ‘[w]e need to get back to the idea of taking responsibility, and this means less celebrity virtue-signalling on Twitter by proxy and more action to tackle the real causes of child poverty’, others have recognised the impact of his effort. One such summary suggested that as the voucher scheme was set to end, the ‘poise, dignity and laser-focused control with which he has carried himself throughout his crusade to stop kids going hungry during the worst pandemic for a century would be impressive from a seasoned politician’.

As with Maradona, Rashford’s politics are deeply informed by his lived experience; and, just as has been suggested of the former, the latter is working to ensure his platform is utilised for those without this privilege his talent and opportunities have afforded him:

“I don’t have the education of a politician, many on Twitter have made that clear […], but I have a social education having lived through this and having spent time with the families and children most affected. These children matter. These children are the future of this country. They are not just another statistic. And for as long as they don’t have a voice, they will have mine’.

Similarly, the dismissal many perpetuate against the women’s game results in a significant mental and emotional demand on professional athletes forced to fight and justify their own place. U.S. midfielder Megan Rapinoe found herself engaged in an intense Twitter battle with the U.S. President Donald Trump, Rapinoe stating, ‘I’m not going to the fucking White House’ if her side were to win the 2019 F.I.F.A. World Cup. As many have noted, Rashford is now being targeted by elements of the right wing corporate press. A young working class black man fortunate to earn the money to ensure comfortable lives for his family, to put his money into community initiatives, and to use to position to directly challenge his own government. It’s another bizarrity, yet, the Football365 website features many better articulated and more socially conscious articles than many mainstream news and the dedicated big name football outlets. One such article, a contribution from John Nicholson, appropriately reads:

“The halogen light of [a] football celebrity being shone into the dark heart of government for the greater good is, it would seem, the only hope we have for them to be held to account, now that so much media scrutiny from press and TV is discounted by all sides as being biased. In this case it has also galvanised 2,000 paediatricians to write in support of him and his cause. Though given this government’s well-known lack of belief in experts and its addiction to dishonesty, maybe without a famous footballer on board, that would make no difference to them”.

Ultimately then, what are the legacies of these athletes?; and what is our role in relation to the sport as supporters? As in July of this year, I reiterate that “[i]nside and out of the stadiums, those of us with an explicit desire to address their own internalised and projected biases must understand the need to proactively challenge broader issues of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, and the like within the communities we associate ourselves with”. We as fans and supporters have our own responsibilities, but those afforded a truly global platform must continue to use theirs.

What’s incredible here is that despite hundreds of charities throughout England (and the U.K. more broadly) dedicated to the eradication or, at least, the reduction of poverty, and the thousands of activists, workers, politicians, and other advocates who’ve spent years or even decades demanding changes to policy, the epistemic authority afforded to Rashford by his platform and supporters based (a base we know transcends his own club) meant he succeeded in changing government policy. Taking academic definitions, Kruglanski, for example, advises that people more readily accept information from those they see as leaders – even in this case where, as Rashford states, that knowledge is organic expertise rather than that of a doctor or a lawyer. When someone like Marcus is worshipped and adored by so many, Kruglanski (1995) suggests that ‘[i]ndividuals process information […] as if the [details] are more definite and certain’, many therein ‘act in accordance with its implications’. In this instance, with Rashford’s leadership, more than one million people signed his online call for the Conservative-led U.K. Government to revise their approach.

What becomes even more incredible – though it can in part be rationalised – is that Rashford’s efforts in England influenced proposed future policy in Scotland. Stating that they were working to combat a ‘second wave of austerity’ and an impending ‘tsunami of child poverty’, the Scottish National Party’s Education Secretary John Swinney announcing that:

“[the S.N.P.] will not leave a child at the mercy of a Tory chancellor just because they are in [primary school years] P4, P5, P6 or P7. If elected next May, from 2022 we will extend universal free school lunches to all primary school pupils, P1 to P7”.

Swinney’s own party colleague, Neil Gray (the party spokesman) previously spoke of his ‘delight[…] that the UK Government appear finally to be relenting to the incredible campaign run by Marcus Rashford’, whilst Swinney singled the player out during his speech, informing his party conference that they intended to expand existing provision for primary school infants ‘because we saw what young leaders like Marcus Rashford saw, what he grew up with’. Thus, even where policy was, not adequate, but at least better than at the U.K. level, Rashford clearly pushed the issue deeper into public consciousness, meaning that – as with votes for prisons (see Votes Behind Bars: Recognising Humanity, Avoiding Responsibility, & Lessons from David Graeber), the S.N.P. want to do but also be seen to be doing better. It’s worth reminding ourselves, however, courtesy of Roz Paterson and Frances Curran, that (whatever the state of the party electorally today), the Scottish Socialist Party advocated free school meals whilst holding six seats in the Scottish Parliament back in 2001 with supporting from many national bodies such as Child Poverty Action Group, the Poverty Alliance, the S.T.U.C.’s Women’s Committee, U.N.I.S.O.N., British Medical Association, Children 1st and the British Medical Association.

And thus, in the week in which Maradona’s body was placed on public display at Casa Rosada in Buenos Aires and the Finding Jack Charlton documentary was publicly released, the ways in which those afforded positions of power, privilege, and access conduct themselves in life merits consideration. Maradona’s natural talent and outspoken political stances afforded him a unique cultural role, whilst Jack Charlton’s leadership created a sense of community during a period of violence and political turmoil. The young boy from the outskirts of Buenos Aires, who spearheaded his youth team, Los Cebollitas, to a one-hundred-and-thirty-six unbeaten run, captains his nation to a World Cup Victory in Mexico 1986, twice broke the world transfer record (in 1982, when he left Boca Juniors for Barcelona; and in 1984 when he signed for Napoli), leaves us with just one illustration of how politics and football remain integrally connected.

Where Maradona offered solidarity to those dominated by imperialism; and Charlton defied hatred and unified a people living through a war (even if only for a time); Rashford has demonstrated the capacity for action in the face of government ineptitude and callousness. In each case, these icons brought hope that another way was possible; and though we must never exclusively rely on others to find or rally behind solutions to poverty, hunger, or many others crises that continue today, the hope that bringing major public presences onside can provide is witnessed in abundance as rejuvenated activists return to the struggle, joined now by those inspired by the hope that the people can defeat callous and uncaring governments.

___________________________

Dear reader, there are two further articles I’d like to draw your attention to. One was shared with me by friend Chloe Maclean which considering how we acknowledge the realities of histories of abuse from those we honour in their deaths:

- Joan Smith. (2020) Tributes to Diego Maradona show how easily violence against women is ignored. The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/nov/27/diego-maradona-violence-women-heroes-abusers?fbclid=IwAR2XRPaYhaQyLgnu1kZqJLkGNcDYR8NDzhYLXiCih_zn_I-Ni5qZ12BKJEg

And the other I’ll leave concerns the harassment Paula Dapena (Viajes InterRías F.F.) has faced since protesting the league’s decision to honour Maradona’s death:

- Justin Vallejo. (2020) Footballer receives death threats after protesting Maradona tribute over abuse claims. The Independent: https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.independent.co.uk/news/world/maradona-domestic-abuse-violence-women-b1764250.html%3famp

It struck me in writing the article how male-centric Maradona’s socialist friendships were, and this is certainly something to consider in more depth going forward.

I can’t help but think that, at least since Beckham, footballing celebrities have supported ‘good causes’ for advertising purposes, the product they’re advertising being themselves. ‘Rashford’ sells. ‘Maradona’ and ‘Ronaldo’ have become multimillion-dollar global brands. Messi won’t be short of a bob or two once he retires.

That’s not to say ‘good causes’ can’t benefit from hanging onto their meteor-trails.

As a one who used to be a long-time follower and fan of football, I appreciate this very thoughtful essay. Far more than merely a look at the sport, societies and our values are also examined…as well as the uses of privilege conferred by notoriety. The appended two linked mentions of articles having to do with male violence and misogyny are significant and also appreciated.

In sum, another substantive contribution to this outstanding site on the internet.

And yet, football is a team sport. Many international sides appear to play worse when their star players are in the team (Scotland’s Women’s team not excepted). What might that say about the relationship between politics and sport? And idolatry is perhaps as immature as the rest of the negative behaviours this article rightly condemns.

Marcus Rashford, for all the good his campaigning has done, is hardly above criticism or controversy (for, say, financial activities and accepting an imperial award).

The celebritisation of sportspeople is not inherent to the game. Transfer fees give a distorting impression of value (and surprise at the replanted star striker whose goals suddenly dry up with a new club is only one symptom of an underlying individualistic bias). All in all, it is another branch of the pernicious Great Man (Occasionally Woman) View of History. And how many of those ‘greats’ were also abusers of various kinds?

Rather than rehashing Maradonna’s champagne socialism, perhaps more insight can be gained from the grassroots where Gabriel Kuhn looks for his book Soccer vs the State: Tackling Football and Radical Politics. Kuhn’s pick from his short segment on social justice campaigns is the FoulBall Campaign targeting child labour, before he goes into more depth about footballing ‘personalities’. He does not shy away from the ugly side of the game, but his interest is more towards cooperation.

https://www.pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=965