Conspirituality – on the overlap between spirituality and conspiracy theories

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land…

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish?

I want to talk about trying to make sense when things are breaking down.

This April we’ve seen some conspiracy theories blooming out of the dead land.

Sports-presenter turned conspiracy-theorist David Icke took centre-stage a week ago, appearing in a video for London Real, in which he claimed COVID19 was caused by 5G, as part of a global plot run by a secret order of alien lizards. The video was watched millions of times on YouTube and on LondonLive before YouTube and Ofcom stepped in to get it taken down.

Four days ago, a documentary appeared called Out of Shadows, recycling the 2016 ‘Pizzagate’ conspiracy theory that a secret order of Democrats and Hollywood celebrities run a paedophile ring centred on two Washington pizza restaurants. The documentary got two million views in a day.

We’ve also seen a conspiracy theory that COVID19 is part of a plot led by Bill Gates and the World Health Organisation to get the world to take his vaccine and implant his chip surveillance. Conspiracy theorists like Alex Jones of Infowars have claimed for over a decade that Gates’ huge funding for vaccines is actually a eugenicist plot to reduce the world’s population. This theory was taken up and enthusiastically spread this week by an anti-vaccine entrepreneur called Dr Shiva, who claims he invented email. A TV interview with him has been watched six million times this week.

Now in some ways this is predictable. The pandemic has led to a breakdown in knowledge and certainty. We don’t know much about the virus or the best way of dealing with it, but we know it’s killing a lot of us and we’re afraid. This is happening to the entire human race at the same time, and we’re all connected on the internet.

This is creating a unique opportunity for fringe beliefs and fringe thinkers to take centre stage. Some might be interesting — Universal Basic Income, say — but some really belong back on the fringe.

I have been disheartened to see leading influencers in my community — that’s to say, western spirituality — spreading the conspiracy theories I mention above. I want my community to be of service to humanity during this crisis, rather than actively spreading bad ideas (particularly anti-vaccine conspiracies — finding a vaccine seems our best hope for getting out of this without 1% of the population, 75 million people, dying of the virus).

It makes me question the worth of my culture. Is spirituality particularly prone to conspiracy thinking?

On the term ‘conspiracy theory’

As various New Age influencers have said this week, ‘conspiracy theory’ is a charged term. It can be a way of simply dismissing a topic without considering it.

Some things dismissed as ‘conspiracy theories’ might really have something behind them. UFOs and extra-terrestrials, for example, are dismissed as conspiracy theories, but to me it seems probable there is life on other planets and that some of it is more intelligent than us.

The idea there was a plot behind JFK’s assassination is another ‘conspiracy theory’ which I think may be more than a theory. Child abuse in the Catholic church is another scandal that could have been dismissed as a conspiracy theory when it really was a conspiracy — ie an epidemic of abuse covered up by the Vatican.

Still, one needs a powerful torch of critical discrimination in these murky and liminal swamp-lands. When you get to Pizzagate, we seem to be very much in the subconscious realm of archetypal, magical thinking — secret symbols and codes, hidden orders of powerful and evil perverts. We are in Dan Brown territory here.

The personality traits behind spirituality and conspiracy thinking

I wondered this week, why should there be an overlap between my community — western spirituality — and conspiracy theories?

My first thought was, there are certain personality traits that make one prone to being ‘spiritual but not religious’ — free thinking, distrust of authority and institutions, a tendency to unusual beliefs or experiences, a tendency to detect ‘hidden’ patterns and correspondences, and an attraction to alternative paradigms, particularly in alternative health — which would all make one more prone to conspiracy theories.

There seems to be some evidence for this. This 2018 study by Hart and Graether, from the Journal of Individual Differences, found, in two surveys of 1200 people, that the strongest predictor of conspiracy thinking was ‘schizotypy’, which is a personality trait that makes one prone to unusual beliefs and experiences, such as belief in telepathy, mind-control, spirit-channelling, hidden personal meanings in events etc. People who are ‘spiritual but not religious’ have been found to score more highly in schizoptypal personality traits than both the religious and the non-religious.

We have to be a little careful here, as there is a risk of tautology. The scientific definition of ‘schizotypal’ basically includes ‘having spiritual beliefs’, so it’s not surprising spiritual people ‘score highly in schizotypy’. So this paper is not really telling us anything other than the sort of people who have spiritual beliefs and experiences are often also into conspiracies. It doesn’t mean they’re wrong or mentally ill. But it may mean they don’t score highly in belief-testing and critical thinking.

This article found that being into ‘spirituality’ and alternative medicine correlated with being anti-vaccines, while this article found both anti-vaxx attitudes and pro-alternative medicine beliefs were connected to magical thinking. You can be pro-vaxx and into spiritual thinking as well, by the way — Larry Brilliant, the epidemiologist who helped eradicate polio, was given his mission by Ram Dass’ guru, Neem Karolio Baba, as he recounts here.

On conspirituality

Finally, two important articles from religious studies. The first is a 2011 article by Ward and Voas from the Journal of Contemporary Religion (behind a paywall alas), on what they describe as the surprising new phenomenon of ‘conspirituality’ — the overlap between New Age spirituality and conspiracy thinking. They describe ‘conspirituality’ as

a rapidly growing web movement expressing an ideology fuelled by political disillusionment and the popularity of alternative worldviews. It has international celebrities, bestsellers, radio and TV stations. It offers a broad politico-spiritual philosophy based on two core convictions, the first traditional to conspiracy theory, the second rooted in the New Age: 1) a secret group covertly controls, or is trying to control, the political and social order, and 2) humanity is undergoing a ‘paradigm shift’ in consciousness. Proponents believe that the best strategy for dealing with the threat of a totalitarian ‘new world order’ is to act in accordance with an awakened ‘new paradigm’ worldview.

This 2015 article, by Egil Apsrem and Asbjorn Dyrendal, responds to Ward and Voas’ article by suggesting ‘conspirituality’ is not a new or surprising phenomenon, but instead emerges from the historical context of the 19th and 20th century ‘occult’. They write:

The cultic milieu is flooded with “all deviant belief systems” and their attendant practices. Moreover, the communication channels within the milieu tend to be as open and fluid as the content that flows through them. The resulting lack of an overarching institutionalized orthodoxy enables individuals to “travel rapidly through a variety of movements and beliefs”, thus bridging with ease what may appear on the surface as distinct discourses and practices. Political, spiritual, and (pseudo)scientific discourses all have a home here, and they easily mix. Joined by a common opposition to “Establishment” discourses rather than by positively shared doctrinal content, conspiracy theory affords a common language binding the discourses together.

In other words, the Occult is a Petri dish for the breeding of all sorts of mutant hybrid memes, some of them helpful, some of them toxic (depending on your worldview).

Ecstatic globalism versus paranoid conspiracy

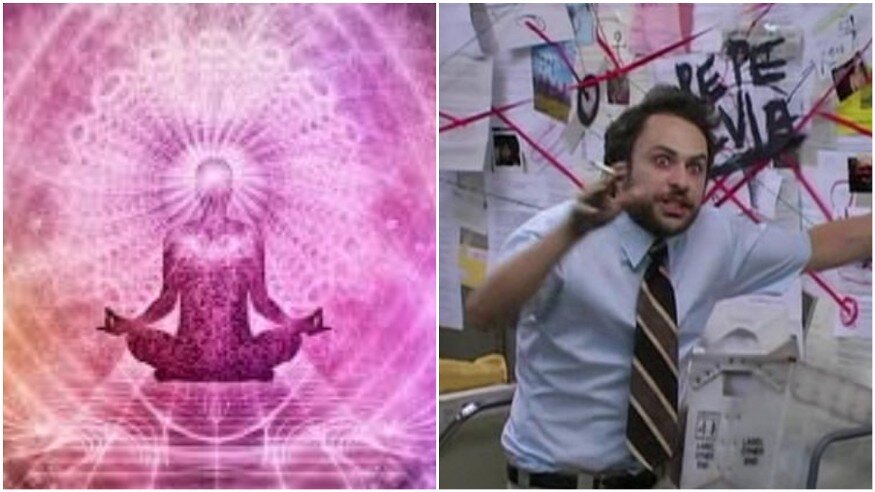

Let me add to this emerging discourse by suggesting that conspirituality theories are a form of mystical or ecstatic experience. I want to compare two forms of mystical experience.

The first is a sort of extroverted euphoric mystical experience: ‘Everything is connected. I am synchronicitously drawn to helpers and allies, the universe is carrying us forward to a wonderful climactic transformation (the Rapture, the Omega Point, the Paradigm Shift) , and we are the heroic warriors of light appointed by God / the Universe to manifest this glorious new phase shift in human history.’

The second is a paranoid ‘bad’ trip version of the euphoric ‘good’ trip. ‘Everything is connected, there is a secret order being revealed to me, but I am not part of it. It is an evil demonic order, and it is trying to control me and everyone else. They have a Grand Plan and it is taking shape now. But perhaps I, and one or two others, can wake up to this Grand Plan, and expose it, and at least hide from it.’

The first trip is a euphoric ego-expansion (I am the Universe!) and the second is paranoid ego-persecution (The Universe is controlled by Evil Demons who are against me!)

In both, the individual awakens to this hidden reality. But in the first, they are a superpowered initiate in the hidden order and a catalyst for a Millennarian transformation, in the second they are a vulnerable and disempowered exposer of the powerful hidden order. (Millennarian, by the way, means that, like Robbie Williams, you believe in a coming Millennium, or Age of Love).

These are two sides of the same coin, two sides in the same game. Both are examples of schizotypal magical / dream thinking. In both, the ego is part of a grand cosmic drama — in the first, they are the divine appointed catalyst for Phase Shift / humanity’s rebirth, in the second, they are the heroic exposer of the Hidden Order.

If we look at the history of the occult (I recommend Gary Lachmann’s Secret Teachers of the Western World as a popular intro), ever since the Reformation there have been secret orders of spiritual-political enthusiasts dedicated to a Millennarian project of global transformation. That’s what Rosicrucians were into, and the Masons, and the Illuminati. So was HG Wells and his ‘Open Conspiracy’— he was supposedly a rationalist, but really he was preaching a sort of occult-scientific polyamorous universalist new religion. So were Theosophists like Annie Besant. So were New Age pioneers in the 1960s like Marilyn Ferguson (author of The Aquarian Conspiracy, one of the best-selling books of the 1980s) and Barbara Hubbard, champion of a globalist evolutionary spirituality. You can probably think of people into this sort of scene today — spiritual-political enthusiasts waiting for a golden New Age of justice, perennial philosophy and polyamorous love.

Globalist Millennarians tend to be quite optimistic and quite well-connected — they connect together with fellow globalist Millennarians through think tanks, associations, conferences, networks and festivals. Barbara Marx Hubbard, the indefatigable champion of ‘evolutionary spirituality’, is an example. She thought homo sapiens was about to ‘phase shift’ into homo universalis, on December 12 2012 to be precise, and she thought she and her friends were the divinely-appointed catalysts for this Millennarian transformation. She was extremely well connected and spread her ideas through all kinds of organisations and networks like the Committee for the Future and the Centre for Integral Wisdom. Indeed, networking was part of her spirituality (she called it ‘supra-sexing’.)

On the other hand, you have conspiracy thinkers who are anti-globalists, like Infowars’ Alex Jones or evangelical Lee Keith (his book cover is below), who may see Millennarian globalists as an evil and demonic hidden order pulling the strings of global events. Anti-globalist paranoid conspiracy thinkers trace the very networks that ecstatic networkers like Barbara Marx Hubbard work through. ‘See!’, they say. ‘They all know each other through these think-tanks and informal organisations.’

False Dawn, by Lee Penn, is an example of paranoid anti-globalist conspiracy thinking — it suggests Barbara Marx Hubbard and other ecstatic globalists are demon-controlled all-powerful hidden order

Where one group are ecstatic, optimistic, super-empowered, insider (and entitled) conspirators, the other are pessimistic, paranoid, disempowered outsiders.

But their thinking styles are in some ways quite similar — schizotypal, magical, prone to seeing secret influences, hidden connections, and Grand Plans. And both massively over-estimate the influence and power of these networks and underestimate the randomness of events.

I think it is possible to be prone to both these forms of magical thinking, to switch between ecstatic, optimistic Millennarianism and paranoid persecutory conspiracy thinking. From ‘everything is connected and I’m a central part of this wonderful cosmic transformation!’’ to ‘everything is connected and I’m at risk from this awful global plot!’ I think someone like Robert Anton Wilson, perhaps, was prone to both sorts of thinking.

The value of the two forms of conspirituality

Now we can dismiss this sort of thinking as simply bullshit religious enthusiasm. Both forms of it. And I feel a strong tendency at the moment to do that, to simply call bullshit on both ecstatic phase-shifters and paranoid conspiracy theorists, and instead try to be as rationalist, sober and un-enthusiastic as possible.

However, this is probably not a very helpful attitude. There is, in fact, a value to both these forms of mystical thinking.

The value in mystical globalism is it can lead to positive things — HG Wells’ ecstatic globalism helped to inspire forms of global governance like the UN Declaration of Human Rights, for example.

However, ecstatic globalism can lead to self-entitlement, to an inflated sense that you are the appointed vanguard of humanity, and that history and the Universe is definitely on your side. That’s dangerous. There can be a dangerous over-concentration of privilege and power, working mainly through informal or undemocratic channels.

The value of conspiracy thinking, meanwhile, can be that it holds power to account. Power can be over-concentrated — the World Health Organisation is excessively reliant on funding by Bill Gates, and the Gates Foundation should be more transparent and accountable, considering the massive influence it has over global public health.

Scientific authority can be awfully, horribly wrong sometimes — many ecstatic globalists in the 20th century supported eugenics ( including HG Wells, Annie Besant, Julian Huxley and Teillard de Chardin). They thought the world should be run by an elite of spiritually enlightened scientists who would decide who was enlightened and who was ‘unfit’ and therefore deserved to be sterilized, locked up, or exterminated. There was no secret conspiracy about this — they proudly declared their opinions. So you can see why paranoid anti-globalists might have their suspicions of secret eugenic plots today.

Balancing the Socratic and the Ecstatic

In general (and in conclusion), there is a value in non-rational forms of knowing, such as dreams, intuitions, inspiration and mystical experiences. These can be important sources of wisdom and healing. Many great scientific discoveries and cultural creations have come from ecstatic or schizotypal inspiration, from Newton’s discovery of gravity to Milton’s Paradise Lost.

I am prone to this sort of ‘benign schizotypy’ myself, and on the whole it enriches my life and work. There is a reason schizotypal thinking has survived for millennia — sometimes it is highly adaptive. It has played an important role in our cultural evolution.

However, it is crucial to balance the capacity for ecstatic / magical / mythical thinking with the capacity for critical thinking. That’s what I’ve tried to do in my books: balance the Socratic and the ecstatic, or the left and right brain, if you’re into that sort of thing.

Too much Socratic thinking without any ecstasy, and you end up with a rather dry and uninspiring worldview. Too much ecstasy without critical thinking, and you may be prone to unhealthy delusions, which you then spread, harming others. You may be so sure you’re right, so hyped in your heroic crusade, you may block things that are really helpful and spread things that are really harmful.

One should be free to believe whatever you want, but in this instance — a global pandemic in the internet age — our beliefs and behaviours profoundly impact others. We need to try and be extra careful in what we believe and what we share, so as to practice mental hygiene.

There is so much fake news out there — I was taken in yesterday by a story that the IMF had cancelled almost all its developing country debt. The story was on a website called IMF2020.org (since taken down). It looked totally reliable. And I so wanted it to be true! I so wanted to share some good news. But alas, it was fake.

We can do a basic test, equivalent to washing our hands.

1) What’s the source? Is it a reliable media organisation? Is it backed up by other reliable sources?

2) How likely is the fact? The less likely, the greater the burden of evidence.

3) Is there anything out there suggesting it’s fake? Rather than looking for evidence to support our beliefs, can we search for evidence against our beliefs?

4) Can we emotionally accept our belief might be wrong?

We can try to practice that sort of mental hygiene on ourselves, but how does one practice effective public communication to counter-act conspiracy thinking? It seems very hard. One’s instinct can be, like Skeptics and New Atheists, simply to call the other side names: ‘idiot, moron, woo-woo, bullshit’ and so on. That sort of shaming probably doesn’t work.

The introduction to the European Journal of Social Psychology’s special ‘conspiracy theory’ issue suggests conspiracy theories are emotionally grounded and socially supported— so an outsider calling you names won’t have much impact. Instead, like de-radicalization or de-culting programmes, perhaps it takes a trusted friend from inside your network to challenge the beliefs in a sympathetic and non-threatening way. That is slow work when one in three Americans believe COVID-19 was made in a laboratory, and one in five Brits say they might not take a COVID-19 vaccine. Our herd immunity to bullshit may be breaking down.

Excellent article.

You neglect however the way leaders like Trump and Johnson ( to name but two) have facilitated conspiracy thinking, if only by theior behaviour for example re David Icke

“in which he claimed COVID19 was caused by 5G, as part of a global plot run by a secret order of alien lizards.”

The Tories ant Trump can be cited as good evidence for this theory (which probably originated with the 1970s SF series “V” , which, I was told, was supposed to be a film about NaoNazis or similar but the company decided on SF)

The show of which you’re thinking is ‘V’, which was based on Sinclair Lewis’ 1930s antifascist novel, It Can’t Happen Here. NBC rejected the initial version, claiming it was too ‘cerebral’ for the average American viewer.

To make the script more marketable, the American fascists were recast as man-eating extraterrestrials. However, the revised version, which screened in the 1980s, did retain the extraterrestrials’ swastika-like emblem, their SS-like uniforms, and their German Luger-like laser weapons in an obvious illusion to National Socialism.

Interestingly, MGM bought the film rights to Lewis’ novel soon after it was published. The script was written and the players cast, but production was indefinitely postponed, due to potential problems in the German market. The film industry’s self-censor, the Production Code Administration, was also concerned that the film would be too prejudicially antifascist and cause offence.

Warner Bros. also fell foul of the PCA when it set out to make a potentially offensive pre-war film about German concentration camps. It took Charlie Chaplin and the Three Stooges to eventually flip the finger to the PCA and its threats of Federal action.

Jules,

Thought provoking article. Dan Brown may have something in his book ‘Origin’, I still need to read it, but on a quick flick through at Waterstones I seem to recall him concluding something about ‘four’.

Something I suspect is true.

I found this very interesting. I was struck by the attention that there was to the Spiritual not religious. Not I’m not sure that the not religious really means. I also believe that the term religious means much more than the conventional faith communities. I would argue strongly that the “No faith communities” can be described as being religions.

I would suggest that it appears that humankind has an irrationality build in (there is a lot of literature to support this).

Perhaps the reason why Religion (IE Faith Systems with a story) has survived despite all its weaknesses is that it gives a reference to the irrationality of faith.

I suspect that the spirituality which is being written about are simply unsystematised and therefore individualist. There is no canon and no orthodoxy, and everyone is coming to something afresh.

Thus it is that there is not a shared experiance, not of belief as in Dogma, but of structure around which belief exists, which is no longer found. It is this which protects society from the wilder ideas.

Never mind ‘religious’, I’m not even sure what ‘spirituality’ means. Its use to denote ‘divine substance’ and, by extension, a charismatic state or power of ‘inspiration’ or ‘enlightenment’ seems to date only from the late 14th century. It would be interesting to trace the genealogy of the whole discourse of ‘spirituality’ as an ideological construct.

It would be even more interesting to trace the genealogy of the assumption that terms like ‘spirituality’ and ‘conspiracy theory’ refer to something ‘beyond’ and independent of language itself and are not just taxonomies.

I once asked a Buddhist monk who was waxing lyrical, what he actually meant by ‘spirituality’. He looked at me quizzically and said interesting question then paused and finally said: ‘what makes you truly happy’. I thought that, in a way, this was quite a good answer.

Aye, but his gnomic answer contains a number of presuppositions that invite query.

First, that ‘spirituality’ refers to some ‘what’ or essence.

Second, that there’s a ‘true’ happiness that can be distinguished from ‘false’ happiness.

I’d have been tempted to then ask him the question of Being: What is the ‘whatness’ of this ‘what’, the ontological status of this thing called ‘spirituality’ – is it noumenal, phenomenal, or merely nominal?

I’d also have been tempted to then ask him the aetiological question: By what criteria do you make the practical distinction between ‘true’ and ‘false’ happiness? And whence does the authority if the criteria you employ in making that distinction derive?

Being a monk and thus having a concern for spirituality and the exploration thereof, I suspect he’d welcome such questions and not just tell me to ‘F*ck off!’

(This is Socratic spirituality in action – the examined life, the eudemon/happiness principle of which is aporia/perplexity.)

Oh yes he would have welcomed them, had I thought of them, or indeed been capable of thinking of them! My question arose from a frustration with the constant use of the word by all sorts, but with a kind of lazy assumption that it actually meant something that could be understood. In other words it was used as a cop out in place of genuine insight and explanation.

Well gollee, Jules, this is a profoundly perceptive analysis; it answers so many questions that it actually, in the great harmonic motion of the universe . . . rings true.

Good vibes, although as some ancient reformer once said . . . we see through a glass darkly . . . and his perspective may have been informed by an earlier sage who compared our experiential awareness to seeing shadows on a cave wall . . .

Even so, getting back to the days of our ancestral cave-dwelling, or even earlier than that . . . perhaps the wisdom of the ages come down this dichotomy:

A person, i.e. homo sapiens, or homo universalis or Joe Blow or Jane Doe, or whoever . . . can spend life drawing sustenance from a tree of life, or . . . wiling away the time between alternating samples from the tree of knowledge of good and/or evil, however you evaluate that . . .

It’s all relative, I mean, we are are all relatives, but maybe there is good in the world, but we certainly see there is evil–no doubt about that.

But if one good person came along to speak for the good side and then got himself in trouble in doing so. . . and got sentenced to a criminal death which was in fact carried out so that that homo universalis turned up dead, but then later resurrected so that, you know, he suffered death and then lived to tell about it . . . well then maybe that might be worthy of some serious consideration, or on the other hand maybe there is something to all conspirational hocus pocus and mumbo jumbo or realspeak or whatever, especially since www renders unto the hearts and minds of homo universalis the metaphysical capability of immediate thought projection into the very hearts of space . . . well then maybe you’re onto something there, Jules.

Keep up the good work.

The fourth point reflects (un)willingness to take your worldview onto a field of decisive contest? While I found the article in parts interesting and explorative, I felt it never really put forward a proposition that could be decisively tested. Have any demon whistleblowers come forward? I caught a glimpse of a women being interviewed on Al Jazeera about her previous involvement in some kind of white supremacist movement. She seemed lucid and there were presumably aspects to her story that could be checked out. Presumably the same would apply to demons.

While I accept there may be ego-blinding, wishful-thinking, need-to-feel-important aspects to this ‘conspirituality’, presumably one of the main problems people have beyond access to information is in integrating it. Therefore this integration of globally-sourced information must be at least partially outsourced, and therefore various collective intelligence processes come in, along with their biases. One of these biases involves the halo effect and recommendation patterns, so that while it may be reasonable to trust one source on one or more topics, that trust is then applied to the source as a whole, and all of their recommendations are (unreasonably) treated as reliable. The halo effect also operates in reverse (not everything, say, Osama Bin Laden said was false or evil, even if you imagine him to be your national number one enemy). Halo effects would seem to apply to gurus, too, and are used by some church abusers (also the Catholic child abuse conspiracies should not be cast in the past tense, there was a story just yesterday on how Jesuits are conspiring to limit the damage but maintain their cover).