If Beith Street Could Talk: ‘Build to Rent’, Studentification and ‘Purpose Built Residential Accommodation’

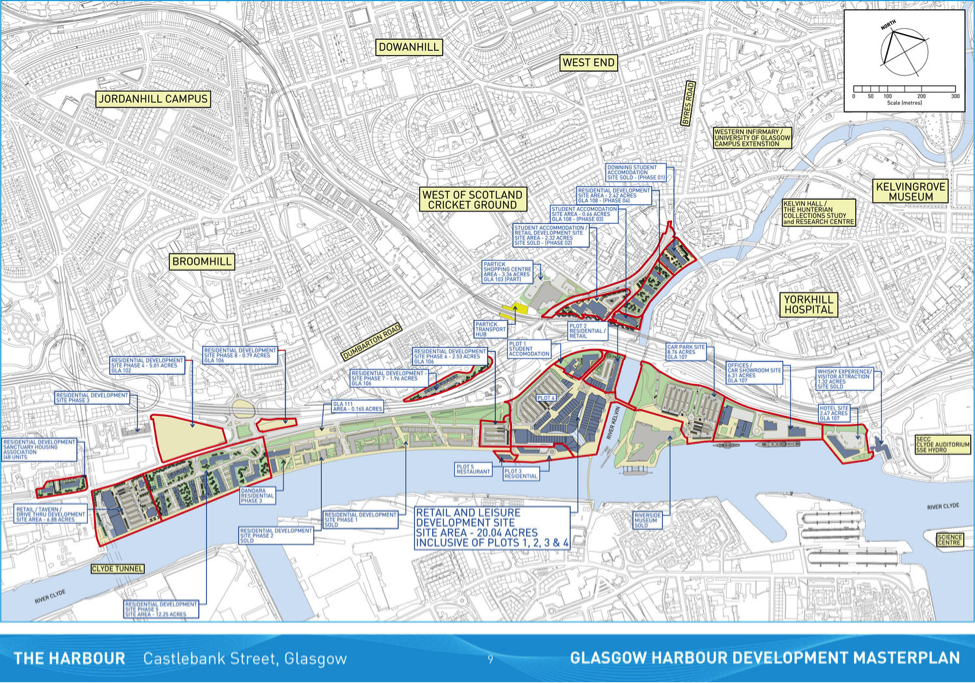

Beith Street lies south of Byres Road in Glasgow’s Hillhead, across Dumbarton Road and into Partick. The vacant site formerly comprised the Partick Central Railway Station, a scrapyard and an occasional showground site. It lies parallel to the River Kelvin as it makes its way south to the River Clyde before veering in a western direction alongside the railway tracks and the Clyde Expressway, which form an east-west barrier between Partick and the Clyde River harbourside. Despite this bifurcation from the Clyde, this section of Beith Street, along with another small section further west, is conceived as part of the Glasgow Harbour Masterplan. Two large-scale student housing blocks have already been constructed there in the mid-2010s, and plans are in place for a contentious 424 private home ‘Built to Rent’ development on the remaining gap site. I will return to developments on Beith Street shortly, but these cannot be understood without reference to the Glasgow Harbour Masterplan.

Note Glasgow Harbour Masterplan, not Partick Harbour Masterplan. This is indicative of a strategy that is not so much aimed at integrating the harbourside with Partick but of generating an intrusive form of ‘new build gentrification’ from the riverside into Partick. Gentrification is now a global urban strategy and is much developed from the simple model of almost incidental bohemian gentrification of working-class areas identified in London in the mid-1960s. The Glasgow Harbour and Clyde Waterfront ‘regeneration’ projects are central planks of Glasgow City Council’s boosterist image of the city as a gleaming, spectacle-laden, entrepreneurial ‘destination’ for upmarket tourists, investors, developers and residents. As one recent Council report states: “It [Glasgow Harbour] will provide VIP and concierge shopping services and will work with agencies, airports and airlines to promote Glasgow to the national and international market”.[1]

The development can be seen as part of Glasgow’s long-inchoate Clyde Waterfront regeneration plan, which began in the early 2000s. The rather meagre results of this project so far are an alienating landscape with a few ‘iconic’ postcard-view buildings scattered along an almost boat-free river, where simple riverside walks (shelter and rest-free) are accessible to only the bravest and most able pedestrians.

The Transport Museum and the Glasgow Science Centre have their merits, but they stand like isolated islands in a sea of planning failure and mediocrity. Any notion of an integrated Masterplan has foundered on a glaring lack of Council vision and coherence and the harsh material reality of limited funds and divided land ownership––Glasgow City Council, Scottish Enterprise and Clydeport (part of Peel Ports Group’s vast empire)––entailing disconnected and contradictory development priorities.[2]

The Harbour Masterplan encompasses 130 acres, stretching from just west of the SECC car park, along through the Transport Museum and the original two phases of private housing in the Glasgow Harbour development (currently undergoing cladding replacement post-Grenfell), to the adjacent Dandara-led third phase currently under construction in Whiteinch, encompassing two 16-storey blocks and 342 Built to Rent flats.

‘Glasgow Harbour East’, lying between Zaha Hadid’s Transport Museum and the first two phases of Glasgow Harbour, is currently seeking planning permission with a plan conceived by Glasgow Harbour Ltd., on behalf of the Peel Group, a major beneficiary of the privatisation of dockyards and harbours throughout the UK, and a voracious waterside land developer. Replete with the usual bullshit exaggerations around jobs creation so typical of regeneration projects,[3] the project promises major footfall, with 5 million potential additional visits to Glasgow per year.[4]

Glasgow Harbour East has already delivered yet more private high-rise student housing in the area at Scotway House. Developed by Structured House Group and managed by their property management arm, BOHO, Scotway House adds another 435 rooms to the tally (prices range from £633 a month for a standard en-suite room to £1,369 for a one-bed apartment). For the remainder of the 15.7-hectare Harbour East site, the latest plans are for a ‘4th generation lifestyle outlet’, incorporating a strictly 1st generation mix of commercial and retail space: restaurants, cafes, 200-room hotel, cinema, casino and waterfront promenade.[5]

For this latest iteration of ‘event and experience’––with a casino snuck in via the latest proposal––expect an upmarket Springfield Quay. There are only so many ways to flog popcorn and only so many cafes and restaurants a city like Glasgow can absorb.

Two sites of land remain in the Masterplan for potential new housing: one very large 6.5-acre site to the immediate west of phases 1-3 of Glasgow Harbour, with the planning potential for 1030 units, almost certainly for private sale or rent; and one small site currently under construction through the Expressway underpass and onto Beith Street/Meadow Road, with 45 new owner-occupied flats. The larger site is where the Harbour Masterplan comes closest to the nearby working-class population, of Whiteinch, since the expressway has diverted inland before this point. Any egregious private development here will be particularly polarising.

The original two phases of private housing at Glasgow Harbour have long been accused of contributing to gentrification in Partick, exhibiting only the most tokenistic connection with the existing community, and blatantly neglecting the housing needs of working-class people in the local area.[6] The aggressive land assetising rentier practices of the Peel Group[7] are in the process of compounding these issues, creating alienating and privatised developer-led waterfront environments the cookie-cutter likes of which depressingly adorn the landscape of pretty much every urban conurbation in the UK.

As shown on Glasgow City Council’s land audit map, there is very limited space for housing development in Partick which is not already undergoing construction or which has not already gained planning consent.[8] Vacant land in the Glasgow Harbour Masterplan area, including Beith Street, contains the vast majority of the remaining land available for housing development.

The City Council has recently accepted a motion to declare a ‘Glasgow rent crisis’ on the back of 42.5% citywide average rent increases for a 2-bed property in the last decade. But concerted plans to grow the private rented sector directly contradict already constrained plans for affordable housing, since the expansion of the sector and rise of rents within it are directly contemporaneous with the collapse and privatisation of public/social housing. Allocating the last vestiges of available land for financialised private housing is severe dereliction of duty with regards to social housing. But then abuse of power comes as no surprise.

Beith Street: ‘Beds for Rent’

Why focus on Beith Street, given the wider issues of the Glasgow Harbour Masterplan?

For one reason, because the condensed space of Beith Street in many ways encapsulates the leading edge of current Scottish Government policy in the private rental sector, exemplifying as it does the development of ‘Purpose Build Residential Accommodation’ (PBRA). Edinburgh-based KR Developments have a track record in student accommodation that synergises with their proposal to fill the gap between existing mass student housing at Beith Street with a new Build to Rent development.

At the same time, numerous objections have been lodged to KR Development’s planning application, and the Partick branch of Living Rent tenants’ union, and other engaged parties, are contesting development as a matter of priority. At least part of the site’s development is a live and contested issue.

The social and public failings of the development are standard for observers of Glasgow developer-led planning priorities. The Beith Street development does not connect Partick with the River Clyde but rather bypasses the area in a finger of new financialised urban development, connecting the high land and property values of the new University of Glasgow campus with Glasgow Harbour. It also cements the historic inability of the Council to open an attractive public walkway from the Kelvingrove Museum via the River Kelvin to the River Clyde, by failing to create and secure public access to the riverside.

More fundamentally, as noted already, the Beith Street development is a striking example of PBRA in Scotland, with three mega-sized student accommodation blocks already in place, comprising 1452 beds in total, and with a planning application lodged for a further four blocks of Build to Rent comprising 424 homes. This would represent a total of 1876 private residential beds in the short stretch between the West Village student blocks, just below Byres Road, and the Vita Student block, just south of Morrisons supermarket in Partick.

In late 2020, there were already 5,465 designated units of student accommodation in South Partick/Yorkhill, and 3,359 in South Partick alone. Besides the alienated and disconnected ‘communities’ that temporary private rental accommodation generates, this is a massive over-concentration of private rented units in a G11 postcode area with average private sector rents for a 2-bedroom flat home at £874 per month, one of the highest averages in the city,[9] and with Glasgow private sector rents for a 2-bedroom flat averaging £848 per month, a 42.5% rise in the last decade.[10]

But the definition of ‘need’ is not neutral, it is generated by discourse by those with most power to decide. Across the UK, property developers and their agents are increasingly seeking to coalesce ‘Purpose Built Student Accommodation’ (PBSA), ‘Build to Rent’ and ‘Co-Living’ (a commodified version of progressive ‘co-housing’ for young professionals which we might term ‘corporate communes’)[11] under one umbrella term: Purpose Built Residential Accommodation (PBRA).

No amount of jargon can conceal the fact that these PBRA developments are simply ‘beds for rent’, and extortionate rent at that. The existing student accommodation at Beith Street rises to £1161 a month for a ‘deluxe studio’ at Vita Student Glasgow. No wonder that the latest count of UK universities on rent strike is 55 out of 140 universities.[12] Any discussion of these rent strikes must contextualise them within the increasingly financialized landscape of student housing provision, which is currently valued at over £50bn.[13]

PBRA is rapidly evolving in the UK as an unholy alliance of funders and developers recognise common ‘opportunities’ for convergence across PBSA, Build to Rent and Co-Living tenures.

Capital has always sought more liquidity in the built environment, which unlike other commodities tends to be ‘fixed’ in time and space with long turnover times. PBRA, contained in single developments with single landlords and management, provides a ‘widget’ or spatial fix for this problem, facilitating the smooth flow of capital through urban space in the form of predictable and standardised features – as opposed to the ‘anarchy of the market’ in variegated landlordism – that promote exchangeability and marketability.

The jargon emanating from promoters of Build to Rent – developers and government – is that leases are from 2-3 years and that quality is higher than in the traditional private rented sector. This may be true. But that is like boasting, with a relative leap of scale, that millionaire penthouses have better standards and conditions than regular housing. It is only of benefit to those who can afford it and does nothing to alter the leasing conditions and quality of existing housing for those on lower incomes.

At the same time, the structural shift towards the promotion and development of PBRA single housing investment portfolios lends itself perfectly to international real estate investment, which is restlessly seeking new markets with steady if not sensational returns, including social housing, after the collapse of the primary mortgage market following the global financial crisis in 2007-2008.[14]

Savills, whose research is integral to UK and Scottish PBRA policy, describe PBRA development as a ‘global search for scale and income producing investments in a low yield environment’.[15] Longer leases mean more security on investments. Let us also remember that high rental prices for student accommodation are often only for rooms with shared facilities and at best for a one-bedroom studio.

Generating new opportunities for financialised capital flow in the built environment, PBRA, in the language of property agents, offers excellent pathways for exploiting “opportunities for operational efficiencies, blended returns and yield compression”.[16] One egregious example is the recent deal by the notorious global corporate landlord, Blackstone, which has just gambled heavily on a post-Brexit future for housing international students by agreeing to purchase the IQ Student Accommodation portfolio (28,000 student beds) from Goldman Sachs for £4.7bn––the UK’s largest ever private real estate transaction.[17]

The extent of the PBRA ‘opportunity’ for investors is such that the landlord class within the UK government are seeking to increase the number of international students by a third, with the major beneficiaries being large-scale, rent-seeking investors. If Co-living as a concept is less developed in Scotland, and partly subsumed within the PBRA offering, Build to Rent, like student accommodation, is a major component of the new PBRA offensive. It is tailor-made for the needs of international real estate investors rather than the needs of the local community where it is imposed by the property lobby and policy wonks.

Build to Rent

Only with the term ‘affordable housing’ so utterly and duplicitously abused and with the British housing system so palpably screwed, could ‘Build to Rent’ be seen as a solution to the affordable housing crisis.[18] Not just an English phenomenon, the Scottish Government, by way of the Scottish Futures Trust since 2016,has been championing Build to Rent and ‘liaising with investors, developers and other stakeholders to stimulate interest in Scotland’. Build to Rent is a product of government policy designed to shift the private market away from Buy to Let by facilitating easier modes of financial investment for large-scale investors.[19] Notably, the main plank of Buy to Let subsidy in Scotland has just been curtailed.

In a heady paroxysm of contradictions, the Scottish Government is simultaneously promoting Build to Rent as transformative for private housing sector growth, yet ‘tenure-blind’ and conducive to ‘mixed-communities’.

The desperate expansion of those renting in the private rented sector is seen by the Scottish Government as a change in ‘demographic behaviour’ (aka consumer choice), rather than an inevitable and desperate result of the decimation and unavailability of public/social housing and the increasing unaffordability of home ownership.[20]

Despite obvious correlations between rising rents, the decline of public/social housing and the growth of the private rented sector, the Scottish Government is pursuing growth in the private rental housing––the tenure with the least security, least affordability and least housing quality for tenants.

This is signaled in the Scottish Government’s ‘Housing to 2040’ draft consultation, where it is recommended that the problem of homeownership affordability be addressed with more commercial investment in the private rented sector (rather than the social housing sector, where it is really required). The benchmark for ‘affordability’ here is not what is affordable to low-income people but what might be affordable to relatively wealthy given the current craziness of the housing market, where even this demographic cannot afford to buy a home.

This baleful and eminently avoidable picture of the growth of the private rented sector, forced by current economic orthodoxy, government policy and an ideological rejection of an appropriate public/social housing policy, is then presented simultaneously as a rational solution to housing shortage for the public and as a profitable opportunity for developers and investors – including pension funds, private equity firms, hedge funds and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) – to dump their surplus capital in the yawning gap between social housing and homeownership through the Build to Rent market.[21]

While politicians shed crocodile tears over the ‘housing affordability crisis’ and ‘Generation Rent’ (a generation, of course, that remains divided by class and access to the ‘bank of mum and dad’), the reality is that – bolstered by research from leading property agents like Savills – they are propping up the property market and its asset-holders by letting them profit even more from a generation of impoverished tenants and would-be homeowners.[22]

It is often assumed, and endlessly recycled by pro-business lobbies, that the public/social housing sector is heavily subsidised. The fact is that subsidies in the private housing sector far outweigh those in the public/social housing sector. In 2017, four times as much (79%) of the UK’s total housing budget was spent on homes for sale, with only around 21% on ‘affordable’ homes to rent (Since the term ‘affordable’ has become almost entirely meaningless, the gap is even more striking when we disaggregate actual social rent from the latter figure). In money terms the comparison is £32bn to £8bn.[23]

Making nonsense of familiar booster narratives of private sector risk-taking and red tape busting entrepreneurialism, it is no surprise that the financialisation of housing in Scotland through the Build to Rent ‘opportunity’ is being facilitated by a ‘Rental Income Guarantee Scheme’ (RIGS). RIGS provides the developer and related investors with ‘greater confidence during the early stages of occupation when the ‘letting risk is likely to be at its highest’, with developers featherbedded by compensation for a portion of the shortfall if ‘expected levels of rent are not achieved’.[24]

This is particularly galling since research has shown that the cost of renting a Build to Rent flat is on average 15% higher than the cost of renting in the buy-to-let market and from 4% to 44% more expensive to rent than comparative local rental markets.[25] With substantial UK government funding available – £1bn for Build to Rent out of a 3.5bn 2014 fund specifically for private rent – no wonder large pension and insurance funds are licking their chops at the prospect of investing in large blocks of flats, which are let out and managed long term by a single company, thus providing institutional security for a stable, long-term income stream.[26]

Data from the British Property Federation shows that, since 2014, Build to Rent has increased in scope from approximately 25,000 units to over 170,000 units completed or in the planning pipeline.[27] In Scotland, Build to Rent development is more recent, but the current figure for developments completed and in the pipeline has increased to forty-four developments comprising 8,653 homes, with Glasgow (4,482) making up more than half of all properties, then Edinburgh (3,077) and Aberdeen (1,094) following.[28]

As a proportion of private rented stock overall, the Build to Rent pipeline is still quite marginal. But it is both heavily promoted by the property and landlord lobby and strongly encouraged by Government, north and south of the border. As ever, the direction of travel is indicated by London, where Build to Rent comprises 7.4% of all PRS stock, compared to the (Dis)United Kingdom (3.4%) and Scotland (2.6%).[29]

Notably, despite claims of contributing to ‘mixed communities’, the sixteen Build to Rent developments in and around Glasgow are almost uniformly clustered in and contribute to the increased gentrification of already highly gentrified areas, such as the Merchant City, the International Financial Services District and the inner River Clyde. In the two isolated examples which veer from this trajectory (Darnick Street, Royston; Abbotsway, Paisley), the developments are ‘mid-market rent’, that most bogus of all ‘affordable’ housing tenures.

In terms of planning obligations (generally understood as a compensatory percentage of affordable housing in large developments), UK Government Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) recommends a 20% benchmark figure for affordable housing in Build to Rent developments. This is significantly below the levels typically sought by local planning authorities.[30]

In Scotland, the guidance is extremely opaque regarding planning obligations,[31] but an enabling planning framework and a comparative tax advantage with England is flaunted to potential investors, with local authorities also being advised to take a ‘flexible approach to design standards and developer contributions’ in Build to Rent developments. Overall, the goal, as ever, is to show that Scotland is ‘open for business’ and to create an ‘attractive planning and investment landscape to support the growth of this sector’.[32] So much for Scottish exceptionalism.

Conclusion

The development of the PBRA market in Scotland is representative of the control of the housing market by large-scale corporate landlords. It is also indicative of the capitulation of local authorities to fleet-footed financial capital in lieu of the proper taxation and public funding that would support the construction of fit-for-purpose quality public, rather than private, housing that is necessary to change the course of the privatising dynamic in the housing landscape.

The housing affordability crisis will not be solved by more Build to Rent homes, which only exacerbate the crisis, but by more social rented homes that low-income people can actually afford. It is firmly established that Build to Rent costs more to rent and inflates neighbourhood rent. It is not a solution for anything but the problem the global financial class has in dumping their surplus wealth profitably.

Ay another level, the PBRA sector, whether in the form of purpose-built student accommodation or Build to Rent in Scotland (Co-living is only in the early stages of development), presents a new kind of problem for tenant activists and housing campaigners. As Kiana Boroumand observes of the rampant student rent strikes across the UK, since global corporate landlords (usually propped up financially by offshored companies) rather than universities maintain much student housing, student resistance between landlord and tenant is complicated.[33]

What is required is closer analysis of the PBSA sector within the overall PBRA sector in order to trace the lineage of ownership that provides the key to challenging the landlord-tenant relation. Yet the form of the PBRA sector, with a single landlord, may also be particularly suited to rent strikes, especially in student accommodation, given that most historical rent strikes have emerged in conditions where tenants were massified together in slum private housing or had the same local authority landlord. Density and single landlordism are key foundations for successful rent strikes.

Moreover, since such developments are so heavily debt-leveraged, rent strikes can reveal the fictions of fictitious capital, which is essentially premised on promissory notes based on potential future revenues. By contesting rental leases with universities and student housing developers, students undermine and disrupt the system of financialisation within which they exist, regardless of whether such an aim has yet been widely articulated or intentioned.

Desiree Fields, one of the most penetrating commentators on the financialisation of the rental housing sector and its discontents, usefully draws out the antagonism between those who privilege the exchange value of housing and those who privilege its use value with the term ‘unwilling subjects of financialisation’. On the one hand, the term reflects on how opaque forms of financialisation constitute tenants and residents as subjects without their knowledge or consent; and on the other, how tenants and residents resist and contest financialised enclosure.

Fields shows how tenant groups in New York subverted the corporate image of private equity firms engaged in private rental investment with the term predatory equity, which described their activity more accurately and became a meme in the media. They also produced mapping projects and databases on money flows and company information, which was picked up by campaign groups, journalists, researchers and sympathetic politicians and public figures. Tenants also followed the ‘spatial form of capital flows’ to develop similar cross-national coordination and solidarity with housing groups across the globe.

What these forms of critical engagement refer to are resistant processes of de-financialisation and de-commodification, an area in urgent need of development in the face of a seemingly faceless and inexorable onslaught by capital on the built environment. Living Rent have already brought attention to the issue of Build to Rent in Scotland with an action at Beith Street and the beginnings of a concerted campaign. I close with a few remarks on how this onslaught might be addressed by tenants and housing groups in a broader sense.

- At the lowest limit, demand that affordable housing levels are met through ‘planning obligations’ in Build to Rent development. At the same time, demand parity of planning obligations with other developments, while acknowledging that the term ‘affordable housing’ in itself has become farcical and urgently requires revision.

- Build to Rent is a relatively new phenomenon in the UK. Tenants and housing groups must actively reveal its social polarising content and make the case for the curtailment of the policy in favour of policies that genuinely addresses the ongoing social housing crisis rather than the requirements of national and international corporate landlords.

- Demand more public housing. This is the most effective means of challenging rising rents and house prices in the private sector. The collapse of public/social housing has typically been blamed on the public debt crisis and budget deficits. Yet, across the OECD, public expenditure on housing overall has never really diminished. The shift in terms of subsidy for private housing over social housing is ideological. It is time to change the discourse.

- Demand that social housing be for genuine social housing in the form of ‘social rent’. Weasel-word tenure forms such as ‘affordable rent’, ‘mid-market rent’, and ‘new supply shared equity’ are not social housing in any traditional sense and move further and further away from genuine public housing. These new forms are merely symptoms of the property lobby’s control of the market, ideological abhorrence of public provision, and a governmental housing system that is unwilling to provide adequate funds for low-income people.

- Demand that a much higher proportion of vacant land, where PBRA is most commonly found, is dedicated to meeting social housing needs.

- Demand a system of rent controls that is effective for tenants, unlike the current Byzantine ‘Rent Pressure Zone’ model.

- Demand that Scotland’s scandalous 50,000 ‘empty homes’ be brought back into use, helped by a campaign for the harmonisation of VAT for Builders, so that refurbishment and repair are granted the same VAT reduction as new-build.

None of this will be achieved without powerful tenant organisation, which is the most effective means of generating policy change. What is clear is that Build to Rent and PBRA are representative of the fact that a fundamental change of thinking is required in Scotland’s housing policy. Such demands will undoubtedly be declared unrealistic by some, but this only reflects how utterly skewed and genuinely unrealistic our current housing system is from the point of view of low-income people. The demands above are not even that radical, no more than that which has already been produced in more social democratic times. Better legislation is clearly necessary, but as history has shown, any progressive reform will only happen when tenants become so effectively organised that politicians are forced into action by pressure from below.[34]

They won’t do it of their own accord. As it stands their ears have been all bent out of shape by a booming property lobby, of which many of them are a part.

Notes

[2] https://policyscotland.gla.ac.uk/glasgows-experience-waterfront-regeneration-success-story/

[3] https://www.monbiot.com/2008/04/01/snow-jobs/

[4] http://glasgowharbour.com/

[6] Paton, K. (2014) Gentrification: A Working-Class Perspective. London: Routledge.

[7] Ward, C and Swyngedouw, E. (2018) Neoliberalisation from the Ground Up: Insurgent Capital, Regional Struggle, and the Assetisation of Land’. Antipode 50(4): 2018.

[8] https://glasgowgis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=1e84b91d0c3f483fb9f2e86554f97deb

[9] https://www.citylets.co.uk/research/reports/property-rental-report-postcode-and-towns-2019-q1/

[10] https://www.citylets.co.uk/research/reports/property-rental-report-glasgow-2020-q3/

[12] https://tribunemag.co.uk/2021/01/britains-historic-wave-of-student-rent-strikes

[13] https://lpeproject.org/blog/what-the-uk-student-rent-strikes-reveal-about-financialization/

[14] Wainwright, T and Manville, G. (2017) Financialization and the third sector: Innovation in social housing bond markets. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49(4): 819-838.

[15] https://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/global-research/world-student-housing-2017-18.pdf

[16] https://www.citylets.co.uk/research/reports/pdf/Citylets-Quarterly-Report-Q3-2020.pdf

[17] https://www.ft.com/content/5f2bc0b8-5876-11ea-abe5-8e03987b7b20

[18] https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2018/apr/11/build-to-rent-developers-profiting-generation-rent

[19] Silver, J., et al. (2021) Walking the financialized city: confronting capitalist urbanization through mobile popular education. Community Development Journal 56(1), 161-179.

[20] https://rigs.rent/storage/uploads/buildtorentopportunity.pdf

[21] https://rigs.rent/storage/uploads/buildtorentopportunity.pdf

[22] https://www.scottishfuturestrust.org.uk/storage/uploads/scottishfuturestrustprsreport_compressed1.pdf

[23] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/affordable-housing-spending-private-tory-government-a7945616.html

[24] https://rigs.rent/

[25] https://www.landlordtoday.co.uk/breaking-news/2019/6/build-to-rent-homes-cost-15-more-than-other-private-rentals

[27] https://bpf.org.uk/about-real-estate/build-to-rent/

[28] https://www.scarlettdev.co.uk/services/build-to-rent/pipeline-scotland/

[29] https://mr0.homeflow.co.uk/files/site_asset/image/3998/3948/BTR_2020.pdf?1591264976

[30] https://www.dlapiper.com/en/uk/insights/publications/2018/11/planning-for-build-to-rent/

[31] https://www.gov.scot/publications/planning-delivery-advice-build-to-rent/

[32] https://rigs.rent/storage/uploads/buildtorentopportunity.pdf

[33] https://lpeproject.org/blog/what-the-uk-student-rent-strikes-reveal-about-financialization/

[34] Gray, N. (2018) Rent and its Discontents: A Century of Housing Struggle. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

This is an area I have got to know well since I retired 11years ago. I actually do walk (and cycle) on the riverside path!

I have watched the gradual evolution of the area over the period. It has been substantially neglected for many decades, having been substantially amputated from Partick and Whiteinch by the motorway, and then the regular demolitions of various former industrial and commercial premises – such as the granary – with the sites being left to moulder and be colonised by weeds.

I remember watching the gradual construction of ‘Glasgow Harbour’ on my week-end cycle rides out to Loch Lomond before it crashed to a halt in 2008 and wondering, “who actually wants to live in an area which is so disconnected from the local districts and the city, as a whole. Perched, as it is beside the Expressway and Clyde Tunnel with their access to motorways, it seemed like an ‘outpost’ of a species of people who have no roots anywhere. (It reminds me of some of the developments in Lewisham, in London, near where my daughter lives, where they commute by DLR from the City and Docklands to concierged flats, but do not interact with the long established areas, such as Deptford.)

I have watched the proliferation of student accommodation. I have explored routes along the Kelvin only to find my path blocked by fencing and buildings that abut the river’s edge but do not acknowledge the Kelvin’s existence.

So,I am substantially in agreement with what the writer is, rather splenetically setting out.

I have used the word ‘splenetically’ intentionally, because I feel that his anger has obscured his communication. The piece falls between an academic article – pretty well researched, as attested by the list of references and polemic, which, sadly is overladen with jargon (which, ironically, he castigates developers for) and imagery which masks the meaning. He would do well to separate this into a genuine academic article and a series of smaller polemics set out (with a less irate style) in clearer language that is more accessible to those, such as I who sat Higher Grade Geography in 1965! Anger is entirely justified and is a sign of sincerity, and a useful motivator, but it can result in blustering incoherence.

Dear Alistair, you say that ‘you are substantially in agreement with the article’ yet the article is incoherent. You do realise that this argument itself is incoherent. I assume an educated and critical audience. Where there is jargon, I have tried to explain it. I think a Bella audience can take it. For the individuals who can’t they can read something lighter elsewhere. Yes, I am angry. Very angry. Partly because I have been watching Glasgow’s urban environment destroyed and commodified beyond words, and partly because I have also seen the results of the policing of critical dialogue in consultations and polite society more generally. But to say that this article is blustering and incoherent, especially when you have already acknowledged its accuracy and sincerity, is offensive and disingenuous. Finally, academic writing itself is extremely ghettoised and stuck behind a paywall in most cases. I prefer a mode of scholarly writing that is well-researched and critical but that aims to disrupt standard separations between academic and popular writing. Variant magazine used to provide a platform for such writing but had its funding curtailed some time ago. Thank you to Mike Small, Bella’s editor, and former contributor in Variant, for also believing that this mode of writing is useful and worthwhile. Little that is useful is easily learned.

Neil,

I did not say the article was ‘incoherent’. Nor did I use the term ‘blustering’.

I indicated why I thought the spleen and anger was valuable.

What I was saying was that I think it was not clear who its audience was. I thought it would have been better as two distinct articles with clearer senses of audience.

The Bella readership is, indeed, pretty well informed, but, not about everything. There have been many articles which I have found immediately informative, but there have been others, where I have found that the terminology is in such a restricted code that I struggle. I have written academic articles myself, but, depending on the audience, I have adopted different registers.

I repeat that I am broadly in agreement with what you have written.

Great article about an on going issue which goes to the heart of what is wrong with the state of the Scottish political scene in general. There seems to be much good will invested in the SNP at the moment, a great deal of it relies on a totally uncritical acceptance of them being notably better than “that Westerminster lot”, yet when you scratch under the surface you find the same corporate agendas at play. The more well researched criticism of the current state of play the better. Not sure why the other commenter thought it fit to mention the style of writing, all seemed pretty digestible to me. Or is the average mental age of the average BC reader substantially lower than I’ve anticipated? Perhaps the author could use some visual aids to get his message across? Margaret Thatcher in a kilt. That kind of thing.